The Feminist Writers' Guild

The Feminist Writers' Guild was an American feminist organization from Berkeley, California, founded by Mary Mackey, Adrienne Rich, Susan Griffin, Charlene Spretnak, and Valerie Miner.[1] Established in 1978, the group was primarily known for their national newsletter. They aimed to augment the feminist movement of the late 1970s by creating a strong network for women writers to communicate and support each other. They promoted works by women regardless of their age, class, race and sexual preference. The FWG published three times a year through a subscription service and accommodated their prices for unemployed or low-income women.[2]

According to an interview with Dodie Bellamy, who was once involved with the Guild, many of the members were made up of both poor and rich women—much like a "Marxist community".[3] Bellamy also said that she found herself standing in rooms with many notable women such as Susan Griffin because of the Guild.

Origins

[edit]According to a note in the Women’s Studies Quarterly by Freedman and Rosaldo, the Feminist Writers Guild started with a group first in Berkeley, California and then a group in New York; by the 1980’s the Feminist Writers’ Guild had more than 1000 members and 16 local chapters. Membership in the 1980’s cost approximately twelve dollars for members, with low-income participants obliged to pay only half of the membership dues. Dubois reported that, “The FWG exists to promote the work of all women and feminist writers including all minorities by age, class, race, sexual preference; Third World women; and women writing in isolation.” According to poet and publisher David Grundy, the rival of the Feminist Writers Guild was the Women Writers Union, a group formed in 1975 out of “struggles at San Francisco State University for more women faculty members and inclusion of women writers in the curriculum.”

Tensions Surrounding Race and Class

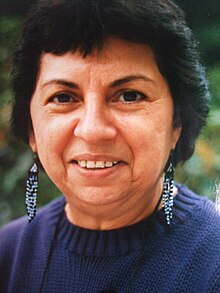

[edit]Critics of the Feminist Writers Guild accused the organization of being too white. Dodie Bellamy, for example, reported that “Many of the guild members were working class and poor, but there were lots of rich women as well.” Writer and activist Gloria Anzaldua was reported to be a member of both of these groups. In his article for the Journal on Narrative Theory, Grundy quotes Anzaldua of saying the following about the Feminist Writers Guild:

“I found this little community of feminist writers in San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley [...] was very much excluding women of color. They interrupted me while I was still talking, or after I had finished they interpreted what I just said according to their thoughts and ideas. [. . .] A lot of them were dykes and very supportive. But they were also blacked out and blinded out about our multiple oppressions. [...] Their idea was that we all were cultureless because we were feminists; we didn’t have any other culture. But they never left their whiteness at home. Their whiteness covered everything they said. However, they wanted me to [. . .] leave my race at the door.”

In his article on Anzaldua’s spiritual writing, author Christopher Tirres expands on Anzaldua’s experience with the Feminist Writers Guild by quoting her published interviews. He includes this statement: “From 1977 to 1981, she lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she joined the Feminist Writers Guild and led a number of writing workshops. But after serving two terms of office at both the local and national levels, Anzaldúa quit because of the racism and alienation she faced from her colleagues, who refused to talk about Third World women, class issues, or oppression (Anzaldúa, Interviews 57).”

Words in Our Pockets

[edit]In 1985, editor Celeste West published Words in Our Pockets: The Feminist Writers’ Guild Handbook on How to Get Published and Get Paid. That publication is still available to purchase through Amazon. Ironically, one of Gloria Anzaldua’s famous essays, “Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers” was first published in this handbook, according to researcher Catherine H. Palczewski in her 1996 article “Bodies, borders, and letters: Gloria Anzaldua's ‘speaking in tongues: A letter to 3rd world women writers,” published in The Southern Communication Journal. The essay later appeared in This Bridge Called My Back and Speaking for Ourselves: Women of the South. According to Palczewski, these publication venues “bring the letter to an audience broader than the one named in its title.”

Other Intersections with Feminist Writers

[edit]Few feminist authors are listed in connection with The Feminist Writers Guild, but several feminist writers allude to connections and interactions in the same circles as those who are widely known and associated with this organization. For example, professor and poet Batya Weinbaum, when writing a piece on a convention of OLOC (Old Lesbians Organizing for Change) in 2015 mentions meeting Adrienne Rich through The Feminist Writers Guild as she was visiting New York City. Writer and poet Danielle Notaro is another writer noted as a member of the Feminist Writers guild in the 1980’s; Notaro seems to be connected with several writing workshops connected with the guild. Weinbaum described Danielle Notaro as “an early member of the Feminist Writers Guild who went on to hold many honors such as Outstanding Spoken Word Artist in Lehigh, PA in 2019” as Weinbaum writes her editor’s notes for the collection of FemSpec in 2020. In similar fashion, an allusion to the service activity of the Feminist Writers Guild appears in a brief essay by Chicago writer SL Wisenberg. In her article entitled “Mexico on $15 a day,” Weisenberg mentioned that the Feminist Writers Guild was collecting books for the Cook County Jail. Although there are few mentions of the Guild still being active, intersections with a who’s who of feminist writers in the 21st century seem abundant in popular press.

The Guild often partnered with other feminist publications such as 13th Moon—whose editor, Ellen Marie Bissert, was also a member of the Guild.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Love, Barbara J., ed. (2006). Feminists Who Changed America. Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 291.

- ^ “Third World Women.” HERESIES, vol. 2, no. 4, 1979. http://heresiesfilmproject.org/archive/

- ^ Buuck, David. “Dodie Bellamy by David Buuck”. BOMB, January 2014. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/dodie-bellamy/

- ^ Dubois, Rochelle H. “The Feminist Writer’s Guild.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, Fall 1981. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1649&context=wsq

- ^ Tirres, Christopher (2018). "Spiritual Realities and Spiritual Activism: Assessing Gloria Anzaldúa's Light in the Dark/Luz En Lo Oscuro". Diálogo. 21 (2): 51–64. doi:10.1353/dlg.2018.0027.

- ^ Weinbaum, Batya (2015). "Femspec Salons at OLOC and NWSA,2015". Femspec. 15 (1): 162–166, 208 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Dubois, Rochelle H. (1981). "The Feminist Writers' Guild". Women's Studies Quarterly. 9 (3): 3–46. ISSN 0732-1562. JSTOR 40003902.

- ^ Freedman, Estelle (1981). "A Note on the Perils of Publicity: The Feminist Studies Program at Stanford". Women's Studies Quarterly. 9 (3): 3. JSTOR 40003900 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Palczewski, Catherine (2020). "Bodies, borders, and letters: Gloria Anzaldua's "speaking in tongues: A letter to 3rd world women writers". The Southern Communication Journal. 62 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/10417949609373035.

- ^ Weinbaum, Batya (2020). "Editor's Corner". Femspec. 20 (1): 5.

- ^ Wisenburg, S.L. (1992). "mexicoon$15aday". North American Review. 277 (6): 14.

- ^ Grundy, David (2021). "New Narratives in Gabrielle Daniels and Ishmael Houston-Jones". Journal of Narrative Theory. 51 (3): 296–325, 415. doi:10.1353/jnt.2021.0014.

- ^ Notaro, Danielle (2020). "arete". Femspec. 20 (1): 22–78.