Auto-Tune

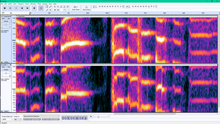

Auto-Tune running on GarageBand | |

| Original author(s) | Andy Hildebrand |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Antares Audio Technologies |

| Initial release | September 19, 1997[1][2] |

| Stable release | 10[3]

|

| Operating system | Windows and macOS |

| Type | Pitch correction |

| License | Proprietary |

| Website | www |

Auto-Tune is audio processor software released on September 19, 1997, by the American company Antares Audio Technologies.[1][4] It uses a proprietary device to measure and correct pitch in music.[5] It operates on different principles from the vocoder or talk box and produces different results.[6]

Auto-Tune was initially intended to disguise or correct off-key inaccuracies, allowing vocal tracks to be perfectly tuned. The 1998 Cher song "Believe" popularized the technique of using Auto-Tune to distort vocals. Cher's song was produced with the assistance of the musical duo Roy Vedas, who had released two months earlier the song "Fragments of Life", which features the technique. It has since been used by many artists in different genres, including Daft Punk, Radiohead, T-Pain and Kanye West. In 2018, the music critic Simon Reynolds observed that Auto-Tune had "revolutionized popular music", calling its use for effects "the fad that just wouldn't fade. Its use is now more entrenched than ever."[7]

Function

[edit]

Auto-Tune is available as a plug-in for digital audio workstations used in a studio setting and as a stand-alone, rack-mounted unit for live performance processing.[8] The processor slightly shifts pitches to the nearest true, correct semitone (to the exact pitch of the nearest note in traditional equal temperament). Auto-Tune can also be used as an effect to distort the human voice when pitch is raised or lowered significantly,[9] such that the voice is heard to leap from note to note stepwise, like a synthesizer.[10]

Auto-Tune has become standard equipment in professional recording studios.[11] Instruments such as the Peavey AT-200 guitar seamlessly use Auto-Tune technology for real-time pitch correction.[12]

Development

[edit]

Auto-Tune was developed by Andy Hildebrand, a Ph.D. research engineer who specialized in stochastic estimation theory and digital signal processing.[1] He conceived the vocal pitch correction technology on the suggestion of a colleague's wife, who had joked that she would benefit from a device to help her sing in tune.[13][7]

Over several months in early 1996, Hildebrand implemented the algorithm on a custom Macintosh computer. Later that year, he presented the result at the NAMM Show, where it became instantly popular.[13] Hildebrand's method for detecting pitch involved autocorrelation and proved superior to attempts based on feature extraction that had problems processing elements such as diphthongs, leading to sound artifacts.[13] Music engineers had previously considered autocorrelation impractical because of the massive computational effort required. Hildebrand found a mathematical method to overcome this, "a simplification [that] changed a million multiply adds into just four".[13]

According to the Auto-Tune patent, the referred implementation detail consists, when processing new samples, of reusing the former autocorrelation bin, and adding the product of the new sample with the older sample corresponding to a lag value, while subtracting the autocorrelation product of the sample that correspondingly got out of window.[5]

Originally, Auto-Tune was designed to discreetly correct imprecise intonations to make music more expressive, with the original patent asserting: "When voices or instruments are out of tune, the emotional qualities of the performance are lost."[7] Auto-Tune was launched in September 1997.[1]

Use

[edit]

The Aphex Twin track "Funny Little Man", from the 1997 EP Come To Daddy, was one of the earliest songs to use Auto-Tune, released less than a month after Auto-Tune.[1][14] The song "Fragments of Life" by the duo Roy Vedas was released on August 17, 1998, heavily using the distorted Auto-Tune technique. Cher's producer, Mark Taylor, heard the song and brought the duo to assist in the production of a song for Cher utilizing similar distortion.[15][16][17] Two months later, Cher's 1998 song "Believe" popularized distorted Auto-Tune vocals.[18] While Auto-Tune was designed to be used subtly to correct vocal performances, the "Believe" producers used extreme settings to create unnaturally rapid corrections in Cher's vocals, thereby removing portamento, the natural slide between pitches in singing.[19] Though Auto-Tune had been commercially available for about a year, according to Pitchfork, "Believe" was the first song "where the effect drew attention to itself ... announcing its technological artifice".[7] In an attempt to protect their method, the producers initially claimed the effect was achieved with a vocoder.[19] It was widely imitated and became known as the "Cher effect".[19]

According to Pitchfork, 1999 "Too Much of Heaven" by the Italian Europop group Eiffel 65 features "the very first example of rapping through Auto-Tune".[7] The Eiffel 65 member Gabry Ponte said they were inspired by Cher's "Believe".[20] The English rock band Radiohead used Auto-Tune on their 2001 album Amnesiac to create a "nasal, depersonalized sound" and to process speech into melody. According to the Radiohead singer, Thom Yorke, Auto-Tune "desperately tries to search for the music in your speech, and produces notes at random. If you've assigned it a key, you've got music."[21]

Later in the 2000s, T-Pain used Auto-Tune extensively, further popularizing the use of the effect.[22] He cited the new jack swing producer Teddy Riley and funk artist Roger Troutman's use of the talk box as inspirations.[18] T-Pain became so associated with Auto-Tune that he had an iPhone app named after him that simulated the effect, "I Am T-Pain".[23] Eventually dubbed the "T-Pain effect",[7] the use of Auto-Tune became a fixture of late 2000s music, where it was used in other hip hop/R&B artists' works, including Snoop Dogg's single "Sexual Eruption",[24] Lil Wayne's "Lollipop",[25] and Kanye West's album 808s & Heartbreak.[26] In 2009 the Black Eyed Peas' number-one hit "Boom Boom Pow", made heavy use of Auto-Tune on their vocals to create a futuristic sound.[7] The use of Auto-Tune in hip hop gained a resurgence in the mid-2010s, especially in trap music. Future and Young Thug are widely considered to be the pioneers of modern trap music and have mentored or inspired popular artists such as Lil Baby, Gunna, Playboi Carti, Travis Scott, and Lil Uzi Vert.[7][27]

The effect has also become popular in raï music and other genres from Northern Africa.[28] According to the Boston Herald, the country singers Faith Hill, Shania Twain, and Tim McGraw use Auto-Tune in performance, calling it a safety net that guarantees a good performance.[29] However, other country singers, such as Allison Moorer,[30] Garth Brooks,[31] Big & Rich, Trisha Yearwood, Vince Gill and Martina McBride, have refused to use Auto-Tune.[32]

Reception

[edit]Positive

[edit]Some critics have argued that Auto-Tune opens up new possibilities in pop music, especially in hip-hop and R&B. Instead of using it as a correction tool for poor vocals—its original purpose—some musicians intentionally use the technology to mediate and augment their artistic expression. When the electronic duo Daft Punk was questioned about their use of Auto-Tune in their single "One More Time", Thomas Bangalter replied, "A lot of people complain about musicians using Auto-Tune. It reminds me of the late '70s when musicians in France tried to ban the synthesizer... They didn't see that you could use those tools in a new way instead of just for replacing the instruments that came before."[33]

T-Pain, the R&B singer and rapper who reintroduced the use of Auto-Tune as a vocal effect in pop music with his album Rappa Ternt Sanga in 2005, said, "My dad always told me that anyone's voice is just another instrument added to the music. There was a time when people had seven-minute songs, and five minutes were just straight instrumental. ... I got a lot of influence from [the '60s era]. I thought I might as well turn my voice into a saxophone."[34] Following in T-Pain's footsteps, Lil Wayne experimented with Auto-Tune between his albums Tha Carter II and Tha Carter III. At the time, he was heavily addicted to promethazine codeine, and some critics see Auto-Tune as a musical expression of Wayne's loneliness and depression.[35] Mark Anthony Neal wrote that Lil Wayne's vocal uniqueness, his "slurs, blurs, bleeps and blushes of his vocals, index some variety of trauma."[36] And Kevin Driscoll asks, "Is Auto-Tune not the wah pedal of today's black pop? Before he transformed himself into T-Wayne on "Lollipop", Wayne's pop presence was limited to guest verses and unauthorized freestyles. In the same way that Miles equipped Hendrix to stay pop-relevant, Wayne's flirtation with the VST plugin du jour brought him updial from JAMN 94.5 to KISS 108."[37]

Kanye West's 808s & Heartbreak was generally well received by critics, and it similarly used Auto-Tune to represent a fragmented soul, following his mother's death.[38] The album marks a departure from his previous album, Graduation. Describing the album as a breakup album, Rolling Stone music critic Jody Rosen wrote, "Kanye can't really sing in the classic sense, but he's not trying to. T-Pain taught the world that Auto-Tune doesn't just sharpen flat notes: It's a painterly device for enhancing vocal expressiveness and upping the pathos ... Kanye's digitized vocals are the sound of a man so stupefied by grief, he's become less than human."[39]

YouTuber Conor Maynard, who received criticism for his use of Auto-Tune, defended it in an interview on the Zach Sang Show in 2019, stating: "It doesn't mean you can't sing ... Auto-Tune can't make anyone who can't sing sound like they can sing ... It just tightens it up slightly because we're human and not perfect, whereas [Auto-Tune] is literally digitally perfect."[40][41]

Negative

[edit]At the 51st Grammy Awards in 2009, the band Death Cab for Cutie made an appearance wearing blue ribbons to protest the use of Auto-Tune.[42] Later that year, Jay-Z titled the lead single of his album The Blueprint 3 as "D.O.A. (Death of Auto-Tune)". Jay-Z said he wrote the song because of personal beliefs that the trend had become a gimmick that had become too widely used.[43][44] Christina Aguilera appeared in public in Los Angeles on August 10, 2009, wearing a T-shirt that read "Auto Tune is for Pussies". When interviewed by Sirius/XM, she said Auto-Tune could be used "in a creative way" and noted her song "Elastic Love" from Bionic uses it.[45]

Opponents have argued that Auto-Tune has a negative effect on society's perception and consumption of music. In 2004, the Daily Telegraph music critic Neil McCormick called Auto-Tune a "particularly sinister invention that has been putting an extra shine on pop vocals since the 1990s" by taking "a poorly sung note and transpos[ing] it, placing it dead centre of where it was meant to be".[46] In 2006, the singer-songwriter Neko Case said a studio employee once told her that she and Nelly Furtado were the only singers who had never used it in his studio. Case said "it's cool that she has some integrity".[47]

In 2009, Time quoted an unnamed Grammy-winning recording engineer as saying, "Let's just say I've had Auto-Tune save vocals on everything from Britney Spears to Bollywood cast albums. And every singer now presumes that you'll just run their voice through the box." The same article expressed "hope that pop's fetish for uniform perfect pitch will fade", speculating that pop-music songs have become harder to differentiate from one another, as "track after track has perfect pitch."[48] According to Tom Lord-Alge, Auto-Tune is used on nearly every record these days.[49]

In 2010, the reality TV show The X Factor admitted to using Auto-Tune to improve the voices of contestants.[50] Also in 2010, Time included Auto-Tune in their list of "The 50 Worst Inventions".[51]

Used by stars from Snoop Dogg and Lil Wayne to Britney Spears and Cher, Auto-Tune has been criticized as indicative of an inability to sing on key.[52][53][54][55][56] Trey Parker used Auto-Tune on the South Park song "Gay Fish", and found that he had to sing off-key in order to sound distorted; he said, "You had to be a bad singer in order for that thing to actually sound the way it does. If you use it and sing into it correctly, it doesn't do anything to your voice."[57] The singer Kesha has used Auto-Tune in her songs extensively, putting her vocal talent under scrutiny.[53][58][59][60][61] In 2009, the producer Rick Rubin wrote that "Right now, if you listen to pop, everything is in perfect pitch, perfect time and perfect tune. That's how ubiquitous Auto-Tune is."[62] The Time journalist Josh Tyrangiel called Auto-Tune "Photoshop for the human voice".[62]

The big band singer Michael Bublé criticized Auto-Tune as making everyone sound the same – "like robots" – but said he used when recording pop music.[63] Ellie Goulding and Ed Sheeran have called for honesty in live shows by joining the "Live Means Live" campaign. "Live Means Live" was launched by songwriter/composer David Mindel. When a band displays the "Live Means Live" logo, the audience knows, "there's no Auto-Tune, nothing that isn't 100 percent live" in the show, and there are no backing tracks.[64] In 2023, multiple creators on the social media platform TikTok were accused of using Auto-Tune in post-production to correct the pitch of singing videos presented to appear as live, casual performances.[65]

Impact and parodies

[edit]The US TV comedy series Saturday Night Live parodied Auto-Tune using the fictional white rapper Blizzard Man, who sang in a sketch: "Robot voice, robot voice! All the kids love the robot voice!"[66][67]

Satirist "Weird Al" Yankovic poked fun at the overuse of Auto-Tune, while commenting that it seemed here to stay, in a YouTube video commented on by various publications such as Wired.[68]

Starting in 2009, the use of Auto-Tune to create melodies from the audio in video newscasts was popularized by Brooklyn musician Michael Gregory, and later by the band the Gregory Brothers in their series Songify the News. The Gregory Brothers digitally manipulated the recorded voices of politicians, news anchors, and political pundits to conform to a melody, making the figures appear to sing.[69][70] The group achieved mainstream success with their "Bed Intruder Song" video, which became the most-watched YouTube video of 2010.[71]

The Simpsons season 12 episode 14, "New Kids on the Blecch", satirizes the use of Auto-Tune. In 2014, during season 18 of the animated show South Park, the character Randy Marsh uses Auto-Tune software to make the singing voice of Lorde. In episode 3, "The Cissy", Randy shows his son Stan how he does it on his computer.[72]

See also

[edit]- Audio time stretching and pitch scaling

- Melodyne, a similar product

- Overproduction (music)

- Robotic voice effects

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Antares News". AntaresTech.com. August 19, 2000. Archived from the original on August 19, 2000. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Preve, Francis. "Antares Kantos 1.0 Audio Synthesizer (PC/Mac)." Keyboard 28, no. 10 (10, 2002): 92-95, 97.

- ^ "Auto-Tune Pro X". Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "AUTO-TUNE". USPTO. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ a b US patent 5973252, Harold A. Hildebrand, "Pitch detection and intonation correction apparatus and method", published 1999-10-26, issued 1999-10-26, assigned to Auburn Audio Technologies, Inc

- ^ Frazier-Neely, Cathryn. "The Independent Teacher—Live Vs. Recorded: Comparing Apples to Oranges to Get Fruit Salad." Journal of Singing – The Official Journal of the National Association of Teachers of Singing 69.5 (2013): 593-6. ProQuest. Web. 16 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Reynolds, Simon (September 17, 2018). "How Auto-Tune revolutionized the sound of popular music". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ "Antares product page". antarestech.com. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Frere Jones, Sasha. "The Gerbil's Revenge Archived 2012-09-09 at archive.today", The New Yorker, June 9, 2008

- ^ "Antares Kantos 1.0." Electronic Musician 18, no. 7 (June 2002): 26. Music Index, EBSCOhost (accessed February 21, 2015).

- ^ Everett-Green, Robert. "Ruled by Frankenmusic," The Globe and Mail, October 14, 2007, p. R1.

- ^ Robair, Gino. "Waves of Innovation" Mix. Jun 2013.Music Index, EBSCOhost (accessed February 21, 2015)

- ^ a b c d Zachary, Crockett (September 26, 2016). "The Mathematical Genius of Auto-Tune". Priceonomics. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "Autotune: good or bad? | CNN Business". CNN. May 26, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "Maxi Trusso estuvo en Italia y se reencontró con Roy Vedas", TN, June 15, 2012

- ^ Oscar Jalil (February 8, 2021), "La historia del Auto-Tune, el dispositivo que abre una nueva grieta en la música", Rolling Stone Argentina, La Nación

- ^ Paula Galloni (July 25, 2018), "Maxi Trusso, el músico argentino que trabajó con Cher y enamoró a una Spice Girl", La Nación

- ^ a b Lee, Chris (November 15, 2008). "The (retro) future is his". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c Frere-Jones, Sasha (June 9, 2008). "The Gerbil's Revenge". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Story of 'Blue (Da Ba Dee)' by Eiffel 65". March 21, 2019.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (July 2001). "Walking on Thin Ice". The Wire. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ Farber, Jim (2007). "Singers do better with T-Pain relief Archived 2009-02-08 at the Wayback Machine", New York DailyNews.

- ^ "I Am T-Pain by Smule - Experience Social Music". iamtpain.smule.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Vocoder Songs - #50 Snoop Dogg - Sexual Eruption". Complex. Complex Media. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ Noz, Andrew. "The 100 Greatest Lil Wayne Songs - #3. Lil Wayne f/ Static Major "Lollipop"". Complex. Complex Media. Archived from the original on December 27, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ Shaheem, Reid (October 15, 2008). "Kanye West's 808s & Heartbreak Album Preview: More Drums, More Singing, 'No Typical Hip-Hop Beats'". MTV. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ^ Warwick, Jacqueline. "Pop". Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Clayton, Jace (May 2009). "Pitch Perfect". Frieze. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ Treacy, Christopher John. "Pitch-adjusting software brings studio tricks," The Boston Herald, February 19, 2007, Monday, "The Edge" p. 32.

- ^ Fitzmaurice, Larry (December 14, 2018). "Great Moments In Auto-Tune History". Vulture. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ Markey, MaKayla (November 13, 2014). "Garth Against the Machine". Country Music Project. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ Vinson, Christina (November 26, 2013). "Big & Rich Not Concerned About Perfection". Taste of Country. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ Gill, Chris (May 1, 2001). "ROBOPOP". Remix. Archived from the original on January 3, 2006. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Zachary Sniderman (December 6, 2011). "T-Pain Talks Autotune, Apps and the Future of Music". Mashable.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "Twitter / noz: @YoPendleton @newbornrodeo". Twitter.com. February 22, 2013. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "A Love Supreme?". Seeingblack.com. October 8, 2008. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "todo mundo » Blog Archive » Is that Lil Twane on the keytar?". Kevindriscoll.info. August 7, 2008. Archived from the original on December 9, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "808s & Heartbreak Reviews". Metacritic. November 25, 2008. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Rosen, Joden (December 11, 2008). "808s & Heartbreak". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "Conor Maynard Talks Hate How Much I Love You, Using Auto-Tune, James Charles & Caspar Lee". YouTube. Archived from the original on January 12, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ "Conor Maynard on Auto-Tune & Why Artists Use It". Archived from the original on December 21, 2021 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Death Cab For Cutie Raise Awareness About Auto-Tune Abuse". mtv.com. February 10, 2009. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ Reid, Shaheem (June 6, 2009). "Jay-Z Premiers New Song, 'D.O.A.': 'Death Of Auto-Tune'". MTV. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Reid, Shaheem (June 10, 2009). "Jay-Z Blames Wendy's Commercial—Partially—For His 'Death Of Auto-Tune'". MTV. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on June 13, 2009. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ Vernallis, Carol; Herzog, Amy; Richardson, John (August 8, 2017). The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Image in Digital Media. OUP USA. ISBN 9780199757640. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (October 13, 2004). "The truth about lip-synching". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ Ryan Dombal (April 10, 2006). "Interview: Neko Case". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on May 1, 2007. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ Tyrangiel, Josh, "Singer's Little Helper Archived 2009-02-10 at the Wayback Machine," Time, 5 February 2009.

- ^ Milner, Greg (2009). Perfecting Sound Forever, p. 343. Faber and Faber. Cited in Hodgson (2010), p. 232.

- ^ "X Factor admits tweaking vocals". BBC News. August 23, 2010. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Auto-Tune: The 50 Worst Inventions Archived 2011-05-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Auto-Tune or How Anyone Can Sing". Up Venue. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Anderson, Vicki (June 14, 2010). "Those who can't sing use auto-tune". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ Williams, Andrew (March 22, 2011). "Danny O'Donoghue: I hate Auto-Tune, it's for people who can't sing". Metro. Associated Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ "Britney unplugged: Can Spears (actually) sing without 'Auto-Tune'?". MSN. Microsoft. Archived from the original on December 28, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ "Auto-Tune (Documentary)". NOVA. PBS. Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ "Trey Parker on Auto-Tuning". YouTube. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Reed, James (April 8, 2011). "The pop star we love to hate". The Boston Globe. NY Times Co. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ Adickman, Erika Brooke (June 30, 2011). "OMG! Ke$ha Admits To Using Auto-Tune". Idolator. Buzz Media. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ "I can sing without Auto-Tune- Kesha". BigPond. Telstra. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ Bosker, Bianca (May 10, 2010). "Ke$ha Claims Not To Use Autotune (VIDEO): Does She Or Doesn't She?". The Huffington Post. AOL. Archived from the original on August 23, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Tyrangiel, Josh (February 5, 2009). "Auto-Tune: Why Pop Music Sounds Perfect". Time. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ "Buble: Auto-Tune is 'overused'". 3 News NZ. April 2, 2013. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014.

- ^ Hardeman, Simon (December 12, 2014). "Live (ish) at a venue near you: Are miming rock stars undermining the music experience?: The rock band that plays completely live, with no pre-recorded backing tracks or extended samples, is becoming rarer and rarer". www.independent.co.uk. Independent. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ^ Crimmins, Tricia. "Those impressive TikTok singing videos might not be for real". The Daily Dot. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Blizzard Man 2 | Saturday Night Live - Yahoo Screen". Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "SNL Transcripts: Tim McGraw: 11/22/08: Blizzard Man". snltranscripts.jt.org. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Thill, Scott (November 16, 2009). "Will Auto-Tune Die? Ask Know Your Meme and 'Weird Al'". Wired. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017.

- ^ "Band's Parody Helps Keep Auto-Tune Alive". [1], John D. Sutter, Time, September 2009

- ^ "Auto-Tune the News" Archived 2010-03-15 at the Wayback Machine, Claire Suddath, Time, April 2009

- ^ "Double rainbows, annoying oranges, and bed intruders: the year on YouTube" Archived 2010-12-23 at the Wayback Machine YouTube Blog, Dec 2010

- ^ Heggs, Melanie (February 21, 2015). "Sia Confirms Involvement In 'South Park' Lorde Parody, 'Chandelier' Singer Figured 'Royals' Artist Would 'Find It Funny'". Fashion & Style. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Ryan Dombal (April 10, 2006). "Interview: Neko Case". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on May 1, 2007. – artistic integrity and Auto-Tune

- CBC Radio One Q: The Podcast for Thursday June 25, 2009 MP3 – NPR's Tom Moon on the takeover of the Auto-Tune.

- "Auto-Tune", NOVA scienceNOW, PBS TV, June 30, 2009

- Andy Hildebrand Interview at NAMM Oral History Collection (2012)