Textual criticism of the New Testament

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (April 2011) |

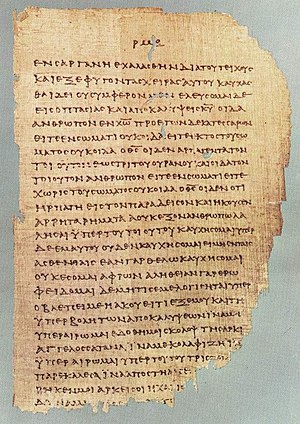

Textual criticism of the New Testament is the identification of textual variants, or different versions of the New Testament, whose goals include identification of transcription errors, analysis of versions, and attempts to reconstruct the original text. Its main focus is studying the textual variants in the New Testament.

The New Testament has been preserved in more than 5,800 Greek manuscripts, 10,000 Latin manuscripts and 9,300 manuscripts in various other ancient languages including Syriac, Slavic, Ethiopic and Armenian. There are approximately 300,000 textual variants among the manuscripts, most of them being the changes of word order and other comparative trivialities.[1][2]

Purpose

[edit]After stating that the Westcott and Hort 1881 critical edition was 'an attempt to present exactly the original words of the New Testament, so far as they can now be determined from surviving documents', Hort (1882) wrote the following on the purpose of textual criticism:

Again, textual criticism is always negative, because its final aim is virtually nothing more than the detection and rejection of error. Its progress consists not in the growing perfection of an ideal in the future, but in approximation towards complete ascertainment of definite facts of the past, that is, towards recovering an exact copy of what was actually written on parchment or papyrus by the author of the book or his amanuensis. Had all intervening transcriptions been perfectly accurate, there could be no error and no variation in existing documents. Where there is variation, there must be error in at least all variants but one; and the primary work of textual criticism is merely to discriminate the erroneous variants from the true.[3]

Text-types

[edit]Historically, attempts have been made to sort new New Testament manuscripts into one of three or four theorized text-types (also styled unhyphenated: text types) or looser clusters.

However, the sheer number of witnesses presents unique difficulties, chiefly in that it makes stemmatics in many cases impossible, because many copyists used two or more different manuscripts as sources. Consequently, New Testament textual critics have adopted eclecticism. The most common division today is as follows:[citation needed]

| Text-type | Date | Characteristics | Bible version |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Alexandrian text-type (also called the "Neutral Text" tradition; less frequently, the "Minority Text") |

2nd–4th centuries CE | When compared to witnesses of the Western text-type, Alexandrian readings tend to be shorter and are commonly regarded as having a lower tendency to expand or paraphrase. Some of the manuscripts representing the Alexandrian text-type have Byzantine corrections made by later hands (Papyrus 66, Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Ephraemi, Codex Regius, and Codex Sangallensis).[4] When compared to witnesses of the Byzantine text type, Alexandrian manuscripts tend to have more abrupt readings and omit verses.[5] It underlies most translations of the New Testament produced since 1900. | NIV, NAB, NABRE, JB and NJB (albeit, with some reliance on the Byzantine text-type), TNIV, NASB, RSV, ESV, EBR, NWT, LB, ASV, NC, GNB, CSB |

| The Western text-type | 3rd–9th centuries CE | The main characteristic of the Western text is a love of paraphrase: "Words and even clauses are changed, omitted, and inserted with surprising freedom, wherever it seemed that the meaning could be brought out with greater force and definiteness."[6] One possible source of glossing is the desire to harmonise and to complete: "More peculiar to the Western text is the readiness to adopt alterations or additions from sources extraneous to the books which ultimately became canonical."[6]

Some modern textual critics doubt the existence of a singular Western text-type, instead viewing it as a group of text-types.[7] |

Vetus Latina, Old Syriac Vulgate New Testament is Vetus Latina base, with Byzantine revisions for the Gospels[8] and Alexandrian revisions for the rest.[9] Used by all Western translations before 1520, including Wycliffite New Testament, original Douay-Rheims The early Armenian[10] and Georgian translations are based on the Old Syriac. |

| The Byzantine text-type | 4th–16th centuries CE | Compared to Alexandrian text-type manuscripts, the distinct Byzantine readings tend to show a greater tendency toward smooth and well-formed Greek, they display fewer instances of textual variation between parallel Synoptic Gospel passages, and they are less likely to present contradictory or "difficult" issues of exegesis.[11] It underlies the Textus Receptus used for most Reformation-era translations of the New Testament. The "Majority Text" methodology effectively produces a Byzantine text-type, because Byzantine manuscripts are the most common and consistent.[1] |

Bible translations relying on the Textus Receptus: KJV, NKJV, Tyndale, Coverdale, Geneva, Bishops' Bible, OSB The Aramaic Peshitta,[12] Wulfila's Gothic translation,[13][14] Ge'ez (Ethiopic), the WEB.[15] |

History of research

[edit]Classification of text-types (1734–1831)

[edit]18th-century German scholars were the first to discover the existence of textual families, and to suggest some were more reliable than others, although they did not yet question the authority of the Textus Receptus.[16] In 1734, Johann Albrecht Bengel was the first scholar to propose classifying manuscripts into text-types (such as 'African' or 'Asiatic'), and to attempt to systematically analyse which ones were superior and inferior.[16] Johann Jakob Wettstein applied textual criticism to the Greek New Testament edition he published in 1751–2, and introduced a system of symbols for manuscripts.[16] From 1774 to 1807, Johann Jakob Griesbach adapted Bengel's text groups and established three text-types (later known as 'Western', 'Alexandrian', and 'Byzantine'), and defined the basic principles of textual criticism.[16] In 1777, Griesbach produced a list of nine manuscripts which represent the Alexandrian text: C, L, K, 1, 13, 33, 69, 106, and 118.[17] Codex Vaticanus was not on this list. In 1796, in the second edition of his Greek New Testament, Griesbach added Codex Vaticanus as witness to the Alexandrian text in Mark, Luke, and John. He still thought that the first half of Matthew represents the Western text-type.[18] In 1808, Johann Leonhard Hug (1765–1846) suggested that the Alexandrian recension was to be dated about the middle of the 3rd century, and it was the purification of a wild text, which was similar to the text of Codex Bezae. In result of this recension interpolations were removed and some grammar refinements were made. The result was the text of the codices B, C, L, and the text of Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria.[19][20]

Development of critical texts (1831–1881)

[edit]

Karl Lachmann became the first scholar to publish a critical edition of the Greek New Testament (1831) that was not simply based on the Textus Receptus anymore, but sought to reconstruct the original biblical text following scientific principles.[16] Starting with Lachmann, manuscripts of the Alexandrian text-type have been the most influential in modern critical editions.[16] In the decades thereafter, important contributions were made by Constantin von Tischendorf, who discovered numerous manuscripts including the Codex Sinaiticus (1844), published several critical editions that he updated several times, culminating in the 8th: Editio Octava Critica Maior (11 volumes, 1864–1894).[16] The 1872 edition provided a critical apparatus listing all the known textual variants in uncials, minuscules, versions, and commentaries of the Church Fathers.[16]

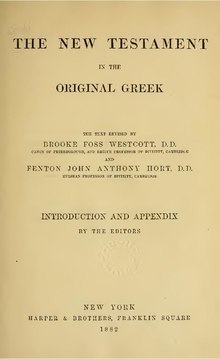

The critical method achieved widespread acceptance up until in the Westcott and Hort text (1881), a landmark publication that sparked a new era of New Testament textual criticism and translations.[16] Hort rejected the primacy of the Byzantine text-type (which he called "Syrian") with three arguments:

- The Byzantine text-type contains readings combining elements found in earlier text-types.

- The variants unique to the Byzantine manuscripts are not found in Christian writings before the 4th century.

- When Byzantine and non-Byzantine readings are compared, the Byzantine can be demonstrated not to represent the original text.[16]

Having diligently studied the early text-types and variants, Westcott and Hort concluded that the Egyptian texts (including Sinaiticus (א) and Vaticanus (B), which they called "Neutral") were the most reliable, since they seemed to preserve the original text with the least changes.[16] Therefore, the Greek text of their critical edition was based on this "Neutral" text-type, unless internal evidence clearly rejected the reliability of particular verses of it.[16]

Until the publication of the Introduction and Appendix of Westcott and Hort in 1882, scholarly opinion remained that the Alexandrian text was represented by the codices Vaticanus (B), Ephraemi Rescriptus (C), and Regius/Angelus (L).[citation needed] The Alexandrian text is one of the three ante-Nicene texts of the New Testament (Neutral and Western).[citation needed] The text of the Codex Vaticanus stays in closest affinity to the Neutral Text.[citation needed]

Modern scholarship (after 1881)

[edit]The Novum Testamentum Graece, first published in 1898 by Eberhard Nestle, later continued by his son Erwin Nestle and since 1952 co-edited by Kurt Aland, became the internationally leading critical text standard amongst scholars, and for translations produced by the United Bible Societies (UBS, formed in 1946).[16] This series of critical editions, including extensive critical apparatuses, is therefore colloquially known as "Nestle-Aland", with particular editions abbreviated as "NA" with the number attached; for example, the 1993 update was the 27th edition, and is thus known as "NA27" (or "UBS4", namely, the 4th United Bible Societies edition based on the 27th Nestle-Aland edition).[16] Puskas & Robbins (2012) noted that, despite significant advancements since 1881, the text of the NA27 differs much more from the Textus Receptus than from Westcott and Hort, stating that 'the contribution of these Cambridge scholars appears to be enduring.'[16]

After discovering the manuscripts 𝔓66 (1952) and 𝔓75 (1950s), the Neutral text and Alexandrian text were unified.[21]

Evaluations of text-types

[edit]Most textual critics of the New Testament favor the Alexandrian text-type as the closest representative of the autographs for many reasons. One reason is that Alexandrian manuscripts are the oldest found; some of the earliest Church Fathers used readings found in the Alexandrian text. Another is that the Alexandrian readings are adjudged more often to be the ones that can best explain the origin of all the variant readings found in other text-types.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, there are some dissenting voices to this consensus. A few textual critics, especially those in France, argue that the Western text-type, an old text from which the Vetus Latina or Old Latin versions of the New Testament are derived, is closer to the originals.[citation needed]

In the United States, some critics have a dissenting view that prefers the Byzantine text-type, such as Maurice A. Robinson and William Grover Pierpont. They assert that Egypt, almost alone, offers optimal climatic conditions favoring preservation of ancient manuscripts while, on the other hand, the papyri used in the east (Asia Minor and Greece) would not have survived due to the unfavourable climatic conditions. Thus, it is not surprising that ancient Biblical manuscripts that are found would come mostly from the Alexandrian geographical area and not from the Byzantine geographical area.[citation needed]

The argument for the authoritative nature of the latter is that the much greater number of Byzantine manuscripts copied in later centuries, in detriment to the Alexandrian manuscripts, indicates a superior understanding by scribes of those being closer to the autographs. Eldon Jay Epp argued that the manuscripts circulated in the Roman world and many documents from other parts of the Roman Empire were found in Egypt since the late 19th century.[22]

The evidence of the papyri suggests that, in Egypt, at least, very different manuscript readings co-existed in the same area in the early Christian period. Thus, whereas the early 3rd century papyrus 𝔓75 witnesses a text in Luke and John that is very close to that found a century later in the Codex Vaticanus, the nearly contemporary 𝔓66 has a much freer text of John; with many unique variants; and others that are now considered distinctive to the Western and Byzantine text-types, albeit that the bulk of readings are Alexandrian. Most modern text critics therefore do not regard any one text-type as deriving in direct succession from autograph manuscripts, but rather, as the fruit of local exercises to compile the best New Testament text from a manuscript tradition that already displayed wide variations.[citation needed]

Textual criticism is also used by those who assert that the New Testament was written in Aramaic (see Aramaic primacy).[23]

Alexandrian text versus Byzantine text

[edit]

The New Testament portion of the English translation known as the King James Version was based on the Textus Receptus, a Greek text prepared by Erasmus based on a few late medieval Greek manuscripts of the Byzantine text-type (1, 1rK, 2e, 2ap, 4, 7, 817).[24] For some books of the Bible, Erasmus used just single manuscripts, and for small sections made his own translations into Greek from the Vulgate.[25] However, following Westcott and Hort, most modern New Testament textual critics have concluded that the Byzantine text-type was formalised at a later date than the Alexandrian and Western text-types. Among the other types, the Alexandrian text-type is viewed as more pure than the Western and Byzantine text-types, and so one of the central tenets in the current practice of New Testament textual criticism is that one should follow the readings of the Alexandrian texts unless those of the other types are clearly superior. Most modern New Testament translations now use an Eclectic Greek text (UBS5 and NA 28) that is closest to the Alexandrian text-type. The United Bible Societies's Greek New Testament (UBS5) and Nestle-Aland (NA 28) are accepted by most of the academic community as the best attempt at reconstructing the original texts of the Greek NT.[26]

A minority position represented by The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text edition by Zane C. Hodges and Arthur L. Farstad argues that the Byzantine text-type represents an earlier text-type than the surviving Alexandrian texts. This position is also held by Maurice A. Robinson and William G. Pierpont in their The New Testament in the Original Greek: Byzantine Textform, and the King James Only Movement. The argument states that the far greater number of surviving late Byzantine manuscripts implies an equivalent preponderance of Byzantine texts amongst lost earlier manuscripts. Hence, a critical reconstruction of the predominant text of the Byzantine tradition would have a superior claim to being closest to the autographs.[citation needed]

Another position is that of the Neo-Byzantine School. The Neo-Byzantines (or new Byzantines) of the 16th and 17th centuries first formally compiled the New Testament Received Text under such textual analysts as Erasmus, Stephanus (Robert Estienne), Beza, and Elzevir. The early 21st century saw the rise of the first textual analyst of this school in over three centuries with Gavin McGrath (b. 1960). A religiously conservative Protestant from Australia, his Neo-Byzantine School principles maintain that the representative or majority Byzantine text, such as compiled by Hodges & Farstad (1985) or Robinson & Pierpont (2005), is to be upheld unless there is a "clear and obvious" textual problem with it. When this occurs, he adopts either a minority Byzantine reading, a reading from the ancient Vulgate, or a reading attested to in the writings of an ancient Church Father (in either Greek or Latin) by way of quotation. The Neo-Byzantine School considers that the doctrine of the Divine Preservation of Scripture means that God preserved the Byzantine Greek manuscripts, Latin manuscripts, and Greek and Latin church writers' citations of Scripture over time and through time. These are regarded as "a closed class of sources" i.e., non-Byzantine Greek manuscripts such as the Alexandrian texts, or manuscripts in other languages such as Armenian, Syriac, or Ethiopian, are regarded as "outside the closed class of sources" providentially protected over time, and so not used to compose the New Testament text.[27] Other scholars have criticized the current categorization of manuscripts into text-types and prefer either to subdivide the manuscripts in other ways or to discard the text-type taxonomy.[citation needed]

Interpolations

[edit]In attempting to determine the original text of the New Testament books, some modern textual critics[who?] have identified sections as interpolations. In modern translations of the Bible such as the New International Version, the results of textual criticism have led to certain verses, words and phrases being left out or marked as not original. Previously, translations of the New Testament such as the King James Version had mostly been based on Erasmus's redaction of the New Testament in Greek, the Textus Receptus from the 16th century based on later manuscripts.[28]

According to Bart D. Ehrman, "These scribal additions are often found in late medieval manuscripts of the New Testament, but not in the manuscripts of the earlier centuries," he adds. And because the King James Bible is based on later manuscripts, such verses "became part of the Bible tradition in English-speaking lands."[29]

Most modern Bibles have footnotes to indicate passages that have disputed source documents. Bible commentaries also discuss such passages, sometimes in great detail.[citation needed]

These possible later additions include the following:[30][31]

- the longer ending of Mark, see Mark 16 (Mark 16:9–20).

- Jesus sweating blood in Luke, Christ's agony at Gethsemane (Luke 22:43–44).

- the story in John of the woman taken in adultery, the Pericope Adulterae (John 7:53–8:11).

- an explicit reference to the Trinity in 1 John, the Comma Johanneum (1 John 5:7–8).

Other disputed NT passages

[edit]Opinions are divided on whether Jesus is referred to as "unique [or only-begotten: Gk. monogenes] Son" or "unique [monogenes] God", in John 1:18[31]

1 Corinthians 14:33–35. Gordon Fee[32] regards the instruction for women to be silent in churches as a later, non-Pauline addition to the Letter, more in keeping with the viewpoint of the Pastoral Epistles (see 1 Tim 2.11–12; Titus 2.5) than of the certainly Pauline Epistles. A few manuscripts place these verses after 40.[33]

Various groups of highly conservative Christians believe that when Ps.12:6–7 speaks of the preservation of the words of God, that this nullifies the need for textual criticism, lower, and higher. Such people include Gail Riplinger, Peter Ruckman, and others. Many theological organisations, societies, newsletters, and churches also hold to this belief, including "AV Publications", Sword of The LORD Newsletter, The Antioch Bible Society[34] and others. On the other hand, Reformation biblical scholars such as Martin Luther saw the academic analysis of biblical texts and their provenance as entirely in line with orthodox Christian faith.[35][36][37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Wallace, Daniel. "The Majority Text and the Original Text: Are They Identical?". Retrieved 23 November 2013. Cite error: The named reference "wallace_on_majority" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Westcott and Hort (1896). The New Testament in The Original Greek: Introduction Appendix. Macmillan. p. 2. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

The New Testament in the Original Greek.

- ^ Westcott and Hort,The New Testament in the original Greek, second edition with Introduction and Appendix (1882), p. 1–3.

- ^ E. A. Button, An Atlas of Textual Criticism, Cambridge, 1911, p. 13.

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2001), pp. 315, 388, 434, 444.

- ^ a b Brooke Foss Westcott, Fenton John Anthony Hort. The New Testament In The Original Greek, 1925. p. 550

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D.; Holmes, Michael W. (2012-11-09). The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis. Second Edition. BRILL. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-90-04-23604-2.

- ^ Chapman, John (1922). "St Jerome and the Vulgate New Testament (I–II)". The Journal of Theological Studies. o.s. 24 (93): 33–51. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXIV.93.33. ISSN 0022-5185. Chapman, John (1923). "St Jerome and the Vulgate New Testament (III)". The Journal of Theological Studies. o.s. 24 (95): 282–299. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXIV.95.282. ISSN 0022-5185.

- ^ Scherbenske, Eric W. (2013). Canonizing Paul: Ancient Editorial Practice and the Corpus Paulinum. Oxford University Press. p. 183.

- ^ Snapp, James. "The Armenian Version of the Gospels".

- ^ "The Syrian text has all the appearance of being a careful attempt to supersede the chaos of rival texts by a judicious selection from them all." Brooke Foss Westcott, Fenton John Anthony Hort. The New Testament In The Original Greek, 1925. p. 551

- ^ Pickering, Wilbur N. (2012). Identity of the New Testament Text III. Wipf & Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4982-6349-8.

- ^ Ratkus, Artūras (6 April 2017). "The Greek Sourcesof the Gothic Bible Translation". Vertimo Studijos. 2 (2): 37. doi:10.15388/VertStud.2009.2.10602.

- ^ Bennett, William, 1980, An Introduction to the Gothic Language, pp. 24-25.

- ^ "World English Bible (WEB) - Version Information - BibleGateway.com". www.biblegateway.com. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Puskas, Charles B; Robbins, C Michael (2012). An Introduction to the New Testament. ISD LLC. pp. 70–73. ISBN 9780718840877.

- ^ J. J. Griesbach, Novum Testamentum Graecum, vol. I (Halle, 1777), prolegomena.

- ^ J. J. Griesbach, Novum Testamentum Graecum, 2 editio (Halae, 1796), prolegomena, p. LXXXI. See Edition from 1809 (London)

- ^ J. L. Hug, Einleitung in die Schriften des Neuen Testaments (Stuttgart 1808), 2nd edition from Stuttgart-Tübingen 1847, p. 168 ff.

- ^ John Leonard Hug, Writings of the New Testament, translated by Daniel Guildford Wait (London 1827), p. 198 ff.

- ^ Gordon D. Fee, P75, P66, and Origen: THe Myth of Early Textual Recension in Alexandria, in: E. J. Epp & G. D. Fee, Studies in the Theory & Method of NT Textual Criticism, Wm. Eerdmans (1993), pp. 247-273.

- ^ Eldon Jay Epp, A Dynamic View of Testual Transmission, in: Studies & Documents 1993, p. 280

- ^ Dunnett & Tenney 1985, p. 150

- ^ W. W. Combs, Erasmus and the textus receptus, DBSJ 1 (Spring 1996), 45.

- ^ Ehrman 2005, "For the most part, he relied on a mere handful of late medieval manuscripts, which he marked up as if he were copyediting a handwritten copy for the printer. ... Erasmus relied heavily on just one twelfth-century manuscript for the Gospels and another, also of the twelfth century, for the book of Acts and the Epistles. ... For the [last six verses of the] Book of Revelation ... [he] simply took the Latin Vulgate and translated its text back into Greek. ..." (pp 78–79)

- ^ Encountering the Manuscripts By Philip Comfort, 102

- ^ "Gavin McGrath Books". www.easy.com.au. Archived from the original on 2010-04-10.

- ^ Hills, Edward (1 July 1998). "A HISTORY OF MY DEFENCE OF THE KING JAMES VERSION". Far Eastern Bible College. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins, 2005, p. 265. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4

- ^ Ehrman 2006, p. 166

- ^ a b Bruce Metzger "A Textual Commentary on the New Testament", Second Edition, 1994, German Bible Society

- ^ See Gordon Fee, First Epistle to the Corinthians, NICNT (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1987), 699.

- ^ Footnotes on 14:34–35 and 14:36 from The HarperCollins Study Bible: New Revised Standard Version: A New Annotated Edition by the Society of Biblical Literature, San Francisco, 1993, page 2160. Note also that the NRSV encloses 14:33b–36 in parentheses to characterize it as a parenthetical comment that does not fit in smoothly with the surrounding texts.

- ^ Antioch Bible Society

- ^ Kramm, H.H. (2009). The Theology of Martin Luther. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-60608-765-7. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ Hendrix, S.H. (2015). Martin Luther: Visionary Reformer. Yale University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-300-16669-9. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ Note, however, that Luther did not exclusively advocate for disinterested historical reconstruction of the original text. See Evans, C.A. (2011). The World of Jesus and the Early Church: Identity and Interpretation in Early Communities of Faith. Hendrickson Publishers. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-59856-825-7. Retrieved 14 May 2017.