List of territorial claims and designations in Colorado

The area currently occupied by the U.S. State of Colorado has undergone numerous changes in occupancy, territorial claims, and political designations. Paleoamericans entered the region about 11,500 BCE,[1] although new research indicates the region may have been visited much earlier.[2] At least nine Native American nations have called the area home. Although Europeans may have entered the region as early as 1540,[3] the first European fort[a] was not constructed until 1819,[4] and the first European town[b] was not established until 1851,[5] primarily due to the opposition of the Ute people. Spain,[6] France,[7] Mexico,[8] and the Republic of Texas[9] have all claimed areas of future state. The United States first claimed an eastern portion of the future state with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.[10][c] The United States surrendered the portion of the region south and west of the Arkansas River to the Spanish Empire with the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1821.[11][d][e] The United States completed its acquisition of the region with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican–American War in 1848.[12] The United States created the free Territory of Colorado in 1861 following the Pikes Peak Gold Rush.[13] The Territory fought for the Union during the American Civil War[14] despite many of its founders being natives of slave states or territories.[15] The Territory of Colorado joined the Union as the State of Colorado in 1876, the centennial year of the United States.[16]

Indigenous peoples

[edit]Indigenous peoples who have lived in the area of the present State of Colorado:

- Paleoamericans[1][2]

- Archaic Period[1]

- Post-Archaic Period[1]

- Ancestral Puebloans[29]

- Native American Nations[31]

- Apache Nation

- Arapaho Nation[f]

- Cheyenne Nation[38][h]

- Comanche Nation[39]

- Kiowa Nation[40]

- Navajo Nation[41]

- Pawnee Nation[42]

- Shoshone Nation

- Ute Nation[j]

- Capote Ute band[54][k][l][m] — native to the upper Rio Grande valley and the San Luis Valley.

- Mouache Ute band[54][k][m] — native to the eastern slope of the Southern Rocky Mountains, from Denver south into New Mexico.

- Parianuche Ute band, later known as the Grand River or White River band[n][o] — native to the upper Colorado River valley.

- Tabeguache Ute band, later known as the Uncompahgre band[l][n][p][o] — native to the Gunnison River and Uncompahgre River valleys.

- Weeminuche Ute band[55][m][q] — native to the San Juan River basin in Colorado and New Mexico.

- Yamparica Ute band, later known as the White River band[n][o] — native to northwestern Colorado.

- Uintah Ute bands including the bands named Cumumba, Pahvant, San Pitch, Sheberetch, Tumpanawach, and Uinta-ats[r] — native to eastern Utah.

Early European claims

[edit]Early Iberian claims in the New World:

- Christopher Columbus (Cristòffa Cómbo) leads his first voyage from August 3, 1492, to March 15, 1493.[56]

- Columbus led the first southern European expedition to the Americas. Columbus substantially underestimated the circumference of the Earth and mistook the Lucayan Archipelago and the Greater Antilles for the southern islands of the Japanese Archipelago. Nevertheless, this expedition became the basis for the Spanish claim to all of the Americas.

The demarcation lines of Inter Caetera (doted purple) and the Treaty of Tordesillas (solid purple)

- Pope Alexander VI issues his papal bull Inter Caetera on May 4, 1493.[57]

- After receiving accounts of the first voyage of Columbus, Valencian Pope Alexander VI issued this papal bull that split the non-Christian world into two halves for Christian exploration, conquest, conversion, and exploitation. The eastern half went to the King of Portugal and the western half (including almost all of the Americas) went to the Queen of Castile and the King of Aragon.

- The Treaty of Tordesillas is signed on June 7, 1494.[58]

- This treaty signed by the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Empire established a new demarcation meridian farther west than the meridian established by the papal bull Inter Caetera. This gave Portugal a much greater portion of Brazil but kept the rest of the Americas under Spanish purview. Pope Julius II sanctioned the treaty with his papal bull Ea quae pro bono pacis issued on January 24, 1506.

- Vasco Núñez de Balboa claims the Mar del Sur (Pacific Ocean) and all adjacent lands for the Queen of Castile on September 29, 1513.[59]

- The members of the Balboa expedition became the first Europeans to reach the eastern Pacific Ocean. The Balboa claim included all of the Americas west of the Continental Divide.

Spanish Empire 1492-1821

[edit]Territorial claims of the Spanish Empire in the area of the present State of Colorado:

- Columbus claims San Salvador for the Catholic Monarchs of Spain on October 12, 1492.

Spanish Empire, 1492-1821

Spanish Empire, 1492-1821- Columbus landed on the Taíno island of Guanahani in the Bahamas which he renamed San Salvador and claimed for Queen Isabel I of Castile and the King Fernando II of Aragon.[56] This claim became the founding basis for the Spanish Empire.

- Hernán Cortés defeats Cuauhtémoc and seizes Tenochtitlán on August 13, 1521.

Viceroyalty of New Spain, 1521-1821

Viceroyalty of New Spain, 1521-1821- Upon his conquest of the Aztec Empire, Cortés renamed Tenochtitlán as México and proclaimed the establishment of Nueva España (New Spain).[60]

- Francisco Vázquez de Coronado leads an expedition north from Compostela on February 23, 1540.

- Coronado led an extensive expedition north from New Spain in search of the mythical Seven Cities of Gold.[3] The expedition explored the future U.S. states of Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and possibly Colorado.

- Juan de Oñate establishes the Spanish colony of Santa Fe de Nuevo Méjico on July 12, 1598.

Santa Fé de Nuevo Méjico, 1598–1821

Santa Fé de Nuevo Méjico, 1598–1821- Oñate established the colony of Santa Fe de Nuevo Méjico at the village of San Juan de los Caballeros adjacent to the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo at the confluence of the río Bravo (Rio Grande) and the río Chama.[6] At its greatest extent, the colony encompassed all of the present U.S. state of New Mexico and portions of Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and the Mexican state of Chihuahua.[s]

- The Adams–Onís Treaty is signed on February 22, 1819, and takes effect on February 22, 1821.

- On February 22, 1819, the United States and the Spanish Empire signed the Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits Between the United States of America and His Catholic Majesty.[11][d] This treaty took effect two years later on February 22, 1821. The Spanish Empire ceded Florida, land east of the Sabine River, and claims north of the 41st parallel north to the United States. The United States ceded a southwestern portion of the Mississippi River basin to the Spanish Empire.

- The Treaty of Córdoba is signed on August 24, 1821.

Santa Fe de Nuevo México 1821–1848

Santa Fe de Nuevo México 1821–1848- With this treaty signed at Córdoba on August 24, 1821, the Spanish Empire acknowledged the independence of the Mexican Empire.[8]

Kingdom of France 1682-1764

[edit]Territorial claim of the Kingdom of France to the Mississippi River basin:[t]

- La Salle claims La Louisiane for King Louis XIV of France on April 9, 1682.

La Louisiane, 1682–1762

La Louisiane, 1682–1762- Having descended the Mississippi River to its mouth, La Salle claimed the entire Mississippi River basin for the King of France on April 9, 1682.[7] This claim ignored Native Americans living in the region. The Spanish Empire disputed the southwestern extent of this claim as encroaching upon its province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México[s] and later Texas. This dispute became moot with the signing of the Treaty of Fontainebleau on November 23, 1762, but arose again with the signing of the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso on October 1, 1800. With the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the question of the southwestern extent of Louisiana became a dispute between the United States and the Spanish Empire.[c]

- The Treaty of Fontainebleau is signed on November 23, 1762, but not announced until September 30, 1764.

La Luisiana, 1762-1801

La Luisiana, 1762-1801- Fearing the loss of all his North American territories as a result of the Seven Years' War (the French and Indian War in North America), King Louis XV of France made this secret pact transferring La Louisiane to his cousin King Carlos III of Spain.[61] Despite the transfer to Spain, the region remained largely Francophone.

Kingdom of Spain 1762-1803

[edit]Territorial claims of the Kingdom of Spain in the Mississippi River basin:[t]

- The Treaty of Fontainebleau is signed on November 23, 1762, but not announced until September 30, 1764.

La Luisiana, 1762-1801

La Luisiana, 1762-1801- King Louis XV of France transferred La Louisiane to King Carlos III of Spain with this secret pact.[61]

- The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso is signed on October 1, 1800.

- Seeking to restore French presence in the Americas, French First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte pressured King Carlos IV of Spain to agree to this secret pact to transfer La Luisiana to the French Republic in exchange for French claims in Tuscany.[62]

- The Treaty of Aranjuez is signed on March 21, 1801.

La Louisiane, 1801–1803

La Louisiane, 1801–1803- This treaty between the French Republic and the Spanish Empire set the terms for the "restoration of La Louisiane to France."[63]

- The Spanish Empire transfers control of La Luisiana to the French Republic on November 30, 1803.

- In a ceremony at Nueva Orleans (New Orleans) on November 30, 1803, Spanish Governor Juan Manuel de Salcedo transferred control of La Luisiana to French Governor Pierre Clement de Laussat.[64] This formal transfer of power was made solely to accommodate the Louisiana Purchase. On March 9, 1804, a similar ceremony was held at San Luis (St. Louis).

French Republic 1800-1803

[edit]Territorial claims of the French Republic in the Mississippi River basin:[t]

- The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso is signed on October 1, 1800.

- Seeking to restore French presence in the Americas, French First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte pressured King Carlos IV of Spain to agree to this secret pact to transfer La Luisiana to the French Republic in exchange for French claims in Tuscany.[62]

- The Treaty of Aranjuez is signed on March 21, 1801.

La Louisiane, 1801–1803

La Louisiane, 1801–1803- This treaty between the French Republic and the Spanish Empire set the terms for the "restoration of La Louisiane to France."[63]

- The Louisiana Purchase is signed on April 30, 1803, announced on July 4, 1803, ratified on October 20, 1803, and transferred on December 20, 1803.

Louisiana Purchase, 1803

Louisiana Purchase, 1803- Wishing to guarantee American navigation rights on the Mississippi River, U.S. President Thomas Jefferson offered to purchase the Mississippi River port of New Orleans from the French Republic. Concerned with the potential cost of future campaigns, French First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte countered with an offer to sell the entire territory of La Louisiane to the United States. Agreeing to a price of 80 million French francs or $15 million U.S. dollars, A Treaty between the United States of America and the French Republic was signed on April 30, 1803.[10]

- The Spanish Empire transfers control of La Luisiana to the French Republic on November 30, 1803.

- In a ceremony at Nueva Orleans (New Orleans) on November 30, 1803, Spanish Governor Juan Manuel de Salcedo transferred control of La Luisiana to French Governor Pierre Clement de Laussat.[64] This formal transfer of power was made solely to accommodate the Louisiana Purchase. On March 9, 1804, a similar ceremony was held at San Luis (St. Louis).

- The French Republic transfers control of La Louisiane to the United States on December 20, 1803.

- On December 20, 1803, in a ceremony at La Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans) only 20 days after the transfer of Spanish control, French Governor Pierre Clement de Laussat transferred control of La Luisiana to U.S. Governor William Claiborne.[64] On March 10, 1804, a similar ceremony was held at Saint-Louis (St. Louis).

Mexico 1821-1848

[edit]Territorial claims of Mexico south and west of the Adams–Onís border:[d]

- The Treaty of Córdoba is signed on August 24, 1821.

Mexican Empire 1821–1823

Mexican Empire 1821–1823- With this treaty signed at Córdoba on August 24, 1821, the Spanish Empire acknowledged the independence of the Mexican Empire.[8]

Mexico 1823–1824

Mexico 1823–1824 Mexican Republic 1824–1835

Mexican Republic 1824–1835

- The Treaty of Limits is signed on January 12, 1828, extended on April 5, 1831, and takes effect on April 5, 1832.

- On January 12, 1828, the United States and the United Mexican States signed the Treaty of Limits between the United States of America and the United Mexican States.[65] On April 5, 1831, the signatories extended the ratification period with an Additional Article to the Treaty of Limits concluded between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, on the 12th day of January, 1828.[66] This treaty took effect one year later on April 5, 1832, and affirmed the border established between the United States and the Spanish Empire by the Adams–Onís Treaty.[d]

Mexican Republic 1835–1846

Mexican Republic 1835–1846

- The Republic of Texas declares its independence from the Mexican Republic on March 2, 1836.[e]

- In 1829, the Mexican Republic banned slavery. Many Texians, Anglo-American immigrants in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, owned slaves. Seven years later on March 2, 1836, the Texians declared their independence as the Republic of Texas.[9] The Mexican Republic refused to recognize the Republic of Texas, although the United States recognized the Republic in 1837.

- The United States annexes the Republic of Texas as the State of Texas on December 29, 1845.

- On December 29, 1845, U.S. President James K. Polk signed the Joint resolution for the admission of the State of Texas into the Union.[67] The United States assumed the territorial claims of the Republic of Texas upon the annexation.[e] The Mexican Republic asserted that the annexation was a violation of the Treaty of Limits. This dispute led to the Mexican–American War.

- The United States declares war on the Mexican Republic on May 13, 1846.

- On May 13, 1846, U.S. President James K. Polk signed An act providing for the prosecution of the existing war between the United States and the Republic of Mexico.[68] The Mexican–American War persisted until 1848.

- The United States Army of the West seizes Santa Fe on August 15, 1846.

- The 1,700 man Army of the West under the command of General Stephen Kearny seized the Nuevo México capital of Santa Fe with little resistance.[69] General Kearny declared himself military governor of New Mexico on August 18, 1846, and established a civilian provisional government of New Mexico.

United Mexican States 1846–1863

United Mexican States 1846–1863

- The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is signed on February 2, 1848, and takes effect on May 30, 1848.

Mexican Cession, 1848–1850

Mexican Cession, 1848–1850- On February 2, 1848, the United States and the United Mexican States signed the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States at Guadalupe Hidalgo.[12] This treaty took effect on May 30, 1848, ending the Mexican–American War. Mexico ceded its extensive northern territory to the United States.

Republic of Texas 1836-1845

[edit]Territorial claim of the Republic of Texas between the Rio Grande and the Adams–Onís border:[d]

- The Republic of Texas declares its independence from the Mexican Republic on March 2, 1836.

Republic of Texas disputed with the Mexican Republic, 1836–1845

Republic of Texas disputed with the Mexican Republic, 1836–1845- On March 2, 1836, Texians, Anglo-American immigrants in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, declared their independence as the Republic of Texas.[9] The Mexican Republic refused to recognize the Republic of Texas, although the United States recognized the Republic in 1837. The Republic of Texas claimed as its eastern and northern border the Adams–Onís border[d] with the United States and as its western and southern border the Rio Grande to its headwaters, thence north along meridian 107°32′35″ west to the Adams–Onís border with the United States.[e]

- The United States annexes the Republic of Texas as the State of Texas on December 29, 1845.

State of Texas disputed with the Mexican Republic, 1845–1848

State of Texas disputed with the Mexican Republic, 1845–1848- On December 29, 1845, U.S. President James K. Polk signed the Joint resolution for the admission of the State of Texas into the Union.[67] The United States assumed the territorial claims of the Republic of Texas upon the annexation.[e] The Mexican Republic asserted that the annexation was a violation of the Treaty of Limits. This dispute led to the Mexican–American War.

United States 1803 to present

[edit]Historical political divisions of the United States in the area of the present State of Colorado:

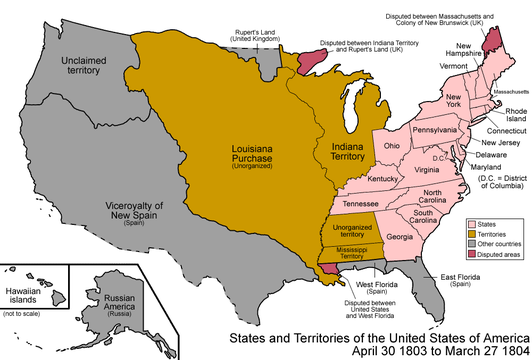

- The Louisiana Purchase is signed on April 30, 1803, announced on July 4, 1803, ratified on October 20, 1803, and transferred on December 20, 1803.

Louisiana Purchase, 1803

Louisiana Purchase, 1803- Wishing to guarantee American navigation rights on the Mississippi River, U.S. President Thomas Jefferson offered to purchase the Mississippi River port of New Orleans from the French Republic. Concerned with the potential cost of future campaigns, French First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte countered with an offer to sell the entire territory of La Louisiane to the United States. Agreeing to a price of 80 million French francs or $15 million U.S. dollars, A Treaty between the United States of America and the French Republic was signed on April 30, 1803.[10] The United States Senate ratified the treaty on October 20, 1803. On October 21, 1803, President Jefferson signed An Act to enable the President of the United States to take possession Oct. 31, 1803, of the territories ceded by France to the United States, by the treaty concluded at Paris, on the thirtieth of April last; and for the temporary government thereof.[70]

- The French Republic transfers control of La Louisiane to the United States on December 20, 1803.

Unorganized territory created by the Louisiana Purchase, 1803–1804

Unorganized territory created by the Louisiana Purchase, 1803–1804- On December 20, 1803, in a ceremony at La Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans) only 20 days after the transfer of Spanish control, French Governor Pierre Clement de Laussat transferred control of La Luisiana to U.S. Governor William Claiborne.[64] On March 10, 1804, a similar ceremony was held at Saint-Louis (St. Louis). The Louisiana Purchase remained unorganized and under military control until it was divided on October 1, 1804, into the Territory of Orleans south of the 33rd parallel north and the District of Louisiana north of the 33rd parallel north.

- The Territory of Orleans and the District of Louisiana are created on October 1, 1804.

District of Louisiana, 1804–1805

District of Louisiana, 1804–1805- On March 26, 1804, U.S. President Thomas Jefferson signed An Act erecting Louisiana into two territories, and providing for the temporary government thereof.[71] The Act created the District of Louisiana on October 1, 1804 from the portion of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 33rd parallel north. The District remained under the jurisdiction of the Indiana Territory until it was reorganized as the Territory of Louisiana on July 4, 1805.

- The Territory of Louisiana is created on July 4, 1805.

Territory of Louisiana, 1805–1812

Territory of Louisiana, 1805–1812- On March 3, 1805, U.S. President Thomas Jefferson signed An Act further providing for the government of the district of Louisiana.[72] The Act reorganized the District of Louisiana as the Territory of Louisiana on July 4, 1805. The Territory was reorganized as the Territory of Missouri on June 4, 1812.

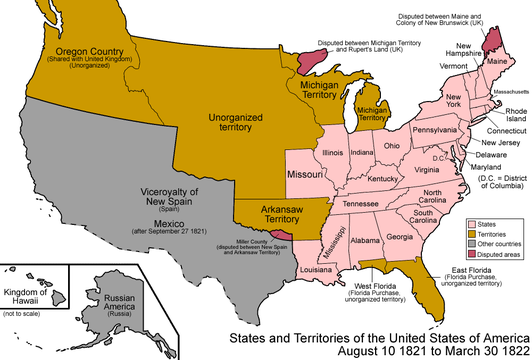

- The Territory of Missouri is created on June 4, 1812.

Territory of Missouri, 1812–1821

Territory of Missouri, 1812–1821- On June 4, 1812, U.S. President James Madison signed An Act providing for the government of the territory of Missouri.[73] The Act reorganized the Territory of Louisiana as the Territory of Missouri. On January 30, 1819, the northern border of the Territory with Rupert's Land was altered by the Anglo-American Convention of 1818. On March 2, 1819, the United States created the Territory of Arkansaw from the southern portion of the Territory. On February 22, 1821, the Adams–Onís Treaty reduced the southwestern extent of the Territory. The Territory existed until the admission of the State of Missouri into the Union on August 10, 1821.

- The Adams–Onís Treaty is signed on February 22, 1819, and takes effect on February 22, 1821.

- On February 22, 1819, the United States and the restored Kingdom of Spain signed the Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits Between the United States of America and His Catholic Majesty.[11][d] This treaty took effect two years later on February 22, 1821. The Spanish Empire ceded Florida, land east of the Sabine River, and claims north of the 41st parallel north to the United States. The United States ceded a southwestern portion of the Mississippi River basin to the Spanish Empire.

- The Missouri Compromise is signed on March 6, 1820.

- On March 6, 1820, U.S. President James Monroe signed An Act to authorize the people of the Missouri territory to form a constitution and state government, and for the admission of such state into the Union on an equal footing with the original states, and to prohibit slavery in certain territories.[74] The Missouri Compromise allowed Missouri to become a slave state, but prohibited slavery in the western territories north of the parallel 36°30′ north.

- The Missouri Statehood Proclamation issued on August 10, 1821.

Unorganized territory previously the northwestern portion of the Missouri Territory, 1821–1854

Unorganized territory previously the northwestern portion of the Missouri Territory, 1821–1854- On August 10, 1821, U.S. President James Monroe certified that the conditions for statehood had been fulfilled and issued Proclamation 28 — Admitting Missouri into the Union.[75] The remaining northwestern portion of the Territory of Missouri became unorganized territory.

- The Treaty of Limits is signed on January 12, 1828, extended on April 5, 1831, and takes effect on April 5, 1832.

- On January 12, 1828, the United States and the United Mexican States signed the Treaty of Limits between the United States of America and the United Mexican States.[65] On April 5, 1831, the signatories extended the ratification period with an Additional Article to the Treaty of Limits concluded between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, on the 12th day of January, 1828.[66] This treaty took effect one year later on April 5, 1832, and affirmed the border established between the United States and the Spanish Empire by the Adams–Onís Treaty.[d]

- The United States annexes the Republic of Texas as the State of Texas on December 29, 1845.

- On December 29, 1845, U.S. President James K. Polk signed the Joint resolution for the admission of the State of Texas into the Union.[67] The United States assumed the territorial claims of the Republic of Texas upon the annexation.[e] The Mexican Republic asserted that the annexation was a violation of the Treaty of Limits. This dispute led to the Mexican–American War.

- The United States declares war on the Mexican Republic on May 13, 1846.

- On May 13, 1846, U.S. President James K. Polk signed An act providing for the prosecution of the existing war between the United States and the Republic of Mexico.[68] The Mexican–American War persisted until 1848.

- The United States Army of the West seizes Santa Fe on August 15, 1846.

- The 1,700 man Army of the West under the command of Brigadier General Stephen Kearny seized the Nuevo México capital of Santa Fe with little resistance.[69] General Kearny assumed command as the first U.S. military governor of New Mexico. On September 22, General Kearny appointed Charles Bent as the first U.S. civilian governor of New Mexico.

- The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is signed on February 2, 1848, and takes effect on May 30, 1848.

- On February 2, 1848, the United States and the United Mexican States signed the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States at Guadalupe Hidalgo.[12] This treaty took effect on May 30, 1848, ending the Mexican–American War. Mexico ceded its extensive northern territory to the United States.

Unorganized territory created by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, 1848–1850

Unorganized territory created by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, 1848–1850- On May 30, 1848, the northern portion of the United Mexican States ceded to the United States becomes unorganized territory.

- The Provisional State of Deseret is formed on March 10, 1849.

Provisional State of Deseret, 1849–1851

Provisional State of Deseret, 1849–1851- On March 10, 1849, the Mormon settlers of the Great Salt Lake Valley formed the Provisional Government of the State of Deseret.[76] Brigham Young was elected Governor. Deseret encompassed almost all of the present U.S. states of Utah and Nevada, and portions of Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and California, although only the Wasatch Front was occupied.[u] The United States created the Territory of Utah on September 9, 1850. Deseret served as the de facto government of the Great Salt Lake Valley until the Provisional State was dissolved on April 4, 1851.

- The Compromise of 1850 is approved on September 9, 1850.

Territory of New Mexico, 1850–1912

Territory of New Mexico, 1850–1912 Territory of Utah, 1850–1896

Territory of Utah, 1850–1896- On September 9, 1850, U.S. President Millard Fillmore signed three bills: An Act proposing to the State of Texas the Establishment of her Northern and Western Boundaries, the Relinquishment by the said State of all Territory claimed by her exterior to said Boundaries, and of all her Claims upon the United States, and to establish a territorial Government for New Mexico,[77] An Act for the admission of the State of California into the Union,[78] and An Act to establish a Territorial Government for Utah.[79] The Territory of Utah existed until January 4, 1896, when it was admitted into the Union as the State of Utah. Utah statehood was delayed over the issue of polygamy in the Territory. The Territory of New Mexico existed until January 6, 1912, when it was admitted into the Union as the State of New Mexico. New Mexico statehood was delayed due to the Spanish origins of the Territory.

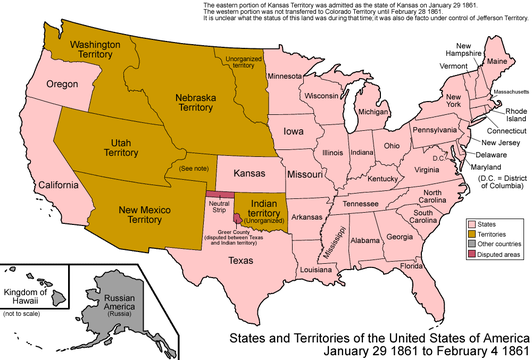

- The Kansas–Nebraska Act is signed on May 30, 1854.

Territory of Kansas, 1854–1861

Territory of Kansas, 1854–1861 Territory of Nebraska, 1854–1867

Territory of Nebraska, 1854–1867- On May 30, 1854, U.S. President Franklin Pierce signed An Act to Organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas.[80] This act superseded the Missouri Compromise and provided for the voters of the territories to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery. The Kansas–Nebraska Act unwittingly led to the American Civil War. The Territory of Kansas existed until January 29, 1861, when it was admitted into the Union as the free State of Kansas. The Territory of Nebraska existed until March 1, 1867, when it was admitted into the Union as the State of Nebraska.

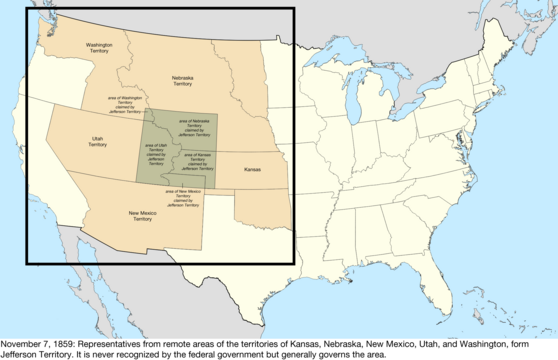

- The Provisional Territory of Jefferson is formed on October 24, 1859.

Provisional Territory of Jefferson, 1859–1861

Provisional Territory of Jefferson, 1859–1861- On October 24, 1859, the settlers in the Pike's Peak region formed the Provisional Government of the Territory of Jefferson and elected Robert Williamson Steele Governor.[81][82] The Jefferson Territory extended from the 102nd meridian west to the 110th meridian west and from the 37th parallel north to the 43rd parallel north, and encompassed all of the present U.S. state of Colorado and portions of Utah, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Kansas.[v] The United States created the Territory of Colorado on February 28, 1861. The Jefferson Territory served as the de facto government of the region until Governor Steele proclaimed the government disbanded on June 6, 1861.

- The Kansas Statehood Act is signed on January 29, 1861.

Unorganized territory previously the western portion of the Kansas Territory, 1861

Unorganized territory previously the western portion of the Kansas Territory, 1861- On January 29, 1861, U.S. President James Buchanan signed An Act for the Admission of Kansas into the Union as a free state.[83] The remaining western portion of the Territory of Kansas became unorganized territory. This area was incorporated into the Territory of Colorado 30 days later on February 28, 1861.

- The Colorado Organic Act is signed on February 28, 1861.

Territory of Colorado, 1861–1876

Territory of Colorado, 1861–1876- On February 28, 1861, U.S. President James Buchanan signed An Act to provide a temporary Government for the Territory of Colorado as a free territory.[13] The Territory of Colorado replaced the Provisional Territory of Jefferson and comprised the unorganized territory previously the western portion of the Territory of Kansas and portions of the Territory of New Mexico, the Territory of Utah, and the Territory of Nebraska. The Colorado Territory existed until it was admitted into the Union as the State of Colorado on August 1, 1876.

- The Colorado Enabling Act is signed on March 3, 1875.

- On March 3, 1875, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant signed An Act to enable the people of Colorado to form a constitution and State government, and for the admission of the said State into the Union on an equal footing with the original States.[84]

- The Colorado Statehood Proclamation issued on August 1, 1876.

State of Colorado, since 1876

State of Colorado, since 1876- On August 1, 1876, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant certified that the conditions of the Colorado Enabling Act had been fulfilled and issued Proclamation 230 — Admission of Colorado into the Union.[16]

Maps

[edit]-

Map of the United States after the Constitution of the United States was ratified on March 4, 1789

-

Map of the United States after the secret Third Treaty of San Ildefonso transferred the Spanish colony of la Luisiana to the French Republic on October 1, 1800

-

Map of the United States after the Louisiana Purchase took effect on December 20, 1803

-

Map of the United States after the creation of the District of Louisiana on March 26, 1804

-

Map of the United States after the creation of the Territory of Louisiana on March 3, 1805

-

Map of the United States after the creation of the Territory of Missouri on June 4, 1812

-

Map of the United States after the Adams–Onís Treaty took effect on February 22, 1821

-

Territorial claims of the Republic of Texas, May 2, 1836

-

Map of the United States after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848

-

Map of the United States after the creation of the provisional State of Deseret on July 2, 1849

-

Map of the United States after the creation of the Territory of New Mexico and the Territory of Utah on September 9, 1850

-

Map of the United States after the creation of the Territory of Kansas and the Territory of Nebraska on May 30, 1854

-

Map of the United States after the creation of the provisional Territory of Jefferson on October 24, 1859

-

Map of the United States after the creation of the Territory of Colorado on February 28, 1861

See also

[edit]- Prehistory of Colorado

- History of Colorado

- Indigenous peoples of the North American Southwest

- Territorial evolution of the United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ The first European building built in the future state of Colorado was the Spanish Fort at Sangre de Cristo Pass.

- ^ The oldest European town in Colorado is San Luis (San Luis de la Culebra) in the San Luis Valley.

- ^ a b In Colorado, the territory disputed between the United States Louisiana Purchase and the Nueva España (New Spain) province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México (New Mexico) included the entire area east of both the Continental Divide and the Sangre de Cristo Divide.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i In Colorado, the border set by the Adams–Onís Treaty between the United States and the Spanish Empire extended up the Arkansas River to its headwaters, thence north along the meridian 106°20'35" west. The United States surrendered the area in the future state south and west of the Arkansas River and east of both the Continental Divide and the Sangre de Cristo Divide. North of the headwaters of the Arkansas River, the border was moved from the Continental Divide to the meridian 106°20'35" west. The Adams–Onís border was affirmed by the Treaty of Limits between the United States and the United Mexican States.

- ^ a b c d e f The Republic of Texas claimed as its eastern and northern border the Adams–Onís border[d] with the United States and as its western and southern border the Rio Grande to its headwaters, thence north along meridian 107°32′35″ west to the Adams–Onís border with the United States. The western extent of this claim was dubious since the Republic of Texas never occupied any territory west of the 102nd meridian west. This claim included half of the Mexican province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, established centuries before in 1598.

- ^ a b On September 17, 1851, leaders of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara nations signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie, 1851[33] at Fort Laramie (Wyoming). Cheyenne and Arapaho people were given a reservation that extended east of the Continental Divide between the Arkansas River and the North Platte River. As whites infiltrated these lands, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation shrank to a mere fraction of its original extent. On October 28, 1867, the leaders of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people signed the Cheyenne and Arapaho Treaty[34] that called for their removal from the Territory of Colorado to a new Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation in Indian Territory. While the Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho people agreed to move southeast to Indian Territory, the Northern Arapaho people refused to move far from their traditional lands and near their traditional enemies. On April 29, 1868, the leaders of the Northern Arapaho people joined with the leaders of the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people and the Yanktonai Dakota people to sign the Treaty of Fort Laramie, 1868[35] at Fort Laramie in the Territory of Dakota. The Treaty called for the tribes to remove to the Great Sioux Reservation in the Territory of Dakota. After a brief stay on the Great Sioux Reservation, the Northern Arapaho wandered west into the Central Rocky Mountains, eventually settling in 1878 with their former enemies on the Shoshone Indian Reservation in the Territory of Wyoming.

- ^ a b In 1878, the Northern Arapaho Tribe settled on the Shoshone Indian Reservation while waiting for the United States to provide a reservation for the tribe. When the United States failed to act, the Northern Arapaho became a fixture of the Shoshone Indian Reservation. It wasn't until the conclusion of the 1938 U.S. Supreme Court Case United States v. Shoshone Tribe of Indians that the government recognized it had wrongly given Shoshone land and resources to the Arapaho. A subsequent land deal then officially solidified Arapaho claim as half-owners of tribal lands and resources on the Shoshone Indian Reservation, which was officially renamed the Wind River Indian Reservation.

- ^ a b On September 17, 1851, leaders of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara nations signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie, 1851[33] at Fort Laramie (Wyoming). Cheyenne and Arapaho people were given a reservation that extended east of the Continental Divide between the Arkansas River and the North Platte River. As whites infiltrated these lands, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation shrank to a mere fraction of its original extent. On October 28, 1867, the leaders of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people signed the Cheyenne and Arapaho Treaty[34] that called for their removal from the Territory of Colorado to a new Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation in Indian Territory.

- ^ On July 3, 1868, leaders of the Eastern Shoshone and Bannock people signed the Fort Bridger Treaty[43] at Fort Bridger in the Territory of Utah. The Treaty called for the Eastern Shoshone and Bannock people to remove to the new Shoshone Indian Reservation.

- ^ On December 30, 1849, Quixiachigiate and 27 other chiefs of the Capote and Mouache Utes and signed the Peace Treaty of Abiquiú[44] at Abiquiú (New Mexico) with new U.S. Indian Commissioner James S. Calhoun. On October 3, 1861, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln signed an executive order reserving the Uinta River Valley in the Territory of Utah for American Indians. On October 7, 1863, leaders of the Tabeguache Utes signed the Tabeguache Treaty[45] at the Tabaquache Agency at Conejos in San Luis Valley. The Tabeguache relinquished all land east of the Continental Divide and Middle Park. Unfortunately, this included land occupied by the Capote Utes. On May 5, 1864, President Lincoln signed "An Act to vacate and sell the present Indian Reservations in Utah Territory, and to settle the Indians of said Territory in the Uinta Valley",[46] unilaterally removing all Indians in the Territory of Utah to the Uinta Valley Reservation. On February 23, 1865, President Lincoln signed "An Act to extinguish the Indian Title to Lands in the Territory of Utah suitable for agricultural and mineral Purposes",[47] expropriating Indian lands in the Territory of Utah outside of the Uinta Valley Reservation. On March 2, 1868, leaders of the seven bands of the Ute Nation signed the Ute Treaty of 1868[48] in Washington, D.C. The Utes were removed to the Consolidated Ute Reservation in the western portion of the Territory of Colorado and the Uinta Valley Reservation in the Territory of Utah. On September 13, 1873, leaders of the seven bands of the Ute Nation signed the Brunot Treaty[49] in Washington, D.C. The Utes relinquished land in the San Juan Mountains desired by miners. On November 9, 1878, leaders of the Capote, Mouache, and Weeminuche Utes signed an agreement at Pagosa Springs, Colorado, establishing the Southern Ute Indian Reservation and relinquishing all other land in Colorado.[50] On March 6, 1880, leaders of the seven bands of the Ute Nation signed the Ute Agreement of 1880[51] at Washington, D.C. The Agreement called for the Tabeguache Utes to remove to the Grand Valley of Colorado and Parianuche and Yamparica Utes to remove to the Uintah Reservation in the Territory of Utah. On January 5, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed an executive order to remove the Tabeguache Utes to the new Uncompahgre Indian Reservation in the Territory of Utah. On July 28, 1882, President Arthur signed An act relating to lands in Colorado lately occupied by the Uncompahgre and White River Ute Indians,[52] expropriating the lands of the Parianuche, Tabeguache, and Yamparica Utes in Colorado. On June 6, 1940, the Weeminuche Utes separated from the Southern Ute Indian Reservation as the Ute Mountain Tribe of the Ute Mountain Reservation.[53]

- ^ a b On December 30, 1849, Quixiachigiate and 27 other chiefs of the Capote and Mouache Utes and signed the Peace Treaty of Abiquiú[44] at Abiquiú (New Mexico) with new U.S. Indian Commissioner James S. Calhoun.

- ^ a b On October 7, 1863, leaders of the Tabeguache Utes signed the Tabeguache Treaty[45] at the Tabaquache Agency at Conejos in San Luis Valley. The Tabeguache relinquished all land east of the Continental Divide and Middle Park. Unfortunately, this included land occupied by the Capote Utes.

- ^ a b c On November 9, 1878, leaders of the Capote, Mouache, and Weeminuche Utes signed an agreement at Pagosa Springs, Colorado, establishing the Southern Ute Indian Reservation and relinquishing all other land in Colorado.[50]

- ^ a b c On March 6, 1880, leaders of the seven bands of the Ute Nation signed the Ute Agreement of 1880[51] at Washington, D.C. The Agreement called for the Tabeguache Utes to remove to the Grand Valley of Colorado and Parianuche and Yamparica Utes to remove to the Uintah Reservation in the Territory of Utah.

- ^ a b c On July 28, 1882, U.S. President Chester A. Arthur signed An act relating to lands in Colorado lately occupied by the Uncompahgre and White River Ute Indians,[52] expropriating the lands of the Parianuche, Tabeguache, and Yamparica Utes in Colorado.

- ^ On January 5, 1882, U.S. President Chester A. Arthur signed an executive order to remove the Tabeguache Utes to the new Uncompahgre Indian Reservation in the Territory of Utah.

- ^ On June 6, 1940, the Weeminuche Utes separated from the Southern Ute Indian Reservation as the Ute Mountain Tribe of the Ute Mountain Reservation.[53]

- ^ On October 3, 1861, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln signed an executive order reserving the Uinta River Valley in the Territory of Utah for American Indians. On May 5, 1864, President Lincoln signed "An Act to vacate and sell the present Indian Reservations in Utah Territory, and to settle the Indians of said Territory in the Uinta Valley",[46] unilaterally removing all Indians in the Territory of Utah to the Uinta Valley Reservation. On February 23, 1865, President Lincoln signed "An Act to extinguish the Indian Title to Lands in the Territory of Utah suitable for agricultural and mineral Purposes",[47] expropriating Indian lands in the Territory of Utah outside of the Uinta Valley Reservation.

- ^ a b At its greatest territorial extent, the Spanish Empire claimed that the border of its colony of New Mexico (Santa Fe de Nuevo México) began where the 31st parallel north crossed 100th meridian west, thence north along the 100th meridian west to the 42nd parallel north, thence west along the 42nd parallel north to the Green River (río Español), thence down the Green River to its confluence with the Colorado River (río Colorado), thence down the Colorado River to its confluence with the Gila River (río Gila), thence up the Gila River up to its confluence with its East Fork and West Fork, thence south along the meridian 108°12′22″ west to the 31st parallel north, thence east along the 31st parallel north back to the 100th meridian west.

- ^ a b c In Colorado, the Mississippi River basin includes all areas east of both the Continental Divide of the Americas and the Sangre de Cristo Divide.

- ^ The Constitution of the State of Deseret[76] states its boundaries as "commencing at the 33 degree of north latitude where it crosses the 108 degree of longitude west of Greenwich thence running south and west to and down the main channel of the Gila River on the northern line of Mexico and on the northern boundary of Lower California to the Pacific Ocean thence along the coast north westerly to 118 degrees 30 minutes of west longitude thence north to where said line intersects the dividing ridge of the Sierra Nevada mountains thence north along the summit of the Sierra Nevada mountains to the dividing range of mountains that separates the waters flowing into the Columbia River from the waters running into the Great Basin thence easterly along the dividing range of mountains that separates said waters flowing into the Columbia River on the north from the waters flowing into the Great Basin on the south to the summit of the Wind River chain of mountains thence south east and south by the dividing range of mountains that separate the waters flowing into the Gulf of Mexico from the waters flowing into the Gulf of California to the place of beginning as set forth in a map drawn by Charles Preuss and published by order of the Senate of the United States in 1848." This ambitious claim included the future cities of Las Vegas, Phoenix, San Diego, and Los Angeles.

- ^ The Constitution of the Provisional Government of the Territory of Jefferson[81] states its boundaries as "Commencing at a point where the 37th degree of north latitude, crosses the 102nd degree of west longitude, and running north on said meridian to the 43d degree of north latitude; thence west on said parallel to the 110th degree of west longitude; thence south on said meridian to the 37th degree of north latitude; thence east on the said parallel to the place of beginning."

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Cassells, E. Steve. (1997). The Archeology of Colorado, Revised Edition. Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Books. pp. 53-54. ISBN 1-55566-193-9.

- ^ a b "Fossilized Footprints". United States National Park Service. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (June 27, 2012). "Francisco Vázquez de Coronado". New Mexico History. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Facundo Melgares". New Mexico History. January 7, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "San Luis". Colorado Encyclopedia. February 11, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Juan de Oñate". New Mexico History. January 10, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Isaac Joslin Cox (1922). "The journeys of Réné Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c The Spanish Empire and the Mexican Empire (August 24, 1821). "The Treaty of Córdoba". Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c The Republic of Texas (March 2, 1836). "The Unanimous Declaration of Independence made by the Delegates of the People of Texas in General Convention at the town of Washington on the 2nd day of March 1836". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c The United States of America and the French Republic (April 30, 1803). "A Treaty between the United States of America and the French Republic". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c The United States of America and the Spanish Empire (February 22, 1819). "Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits Between the United States of America and His Catholic Majesty". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c The United States of America and the United Mexican States (February 2, 1848). "Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Thirty-sixth United States Congress (February 28, 1861). "An Act to provide a temporary Government for the Territory of Colorado" (PDF). p. 172. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Ovando J. Hollister (1962). "Colorado volunteers in New Mexico, 1862". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Civil War in Colorado". Colorado Encyclopedia. April 26, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Ulysses S. Grant (August 1, 1876). "Proclamation 230—Admission of Colorado into the Union". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Fisher, Jr., John W. N.D. Observations on the Late Pleistocene Bone Bed Assemblage from the Lamb Spring Site, Colorado. In Ice Age Hunters of the Rockies by Dennis Stanford and Jane S. Day, pp. 51–81. Denver Museum of Natural History; Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1992

- ^ Kathryn A. Hoppe (July 29, 2003). "Late Pleistocene mammoth herd structure, migration patterns, and Clovis hunting strategies inferred from isotopic analyses of multiple death assemblages" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2006. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Wilmsen, E.N.; Roberts, F.H.H. (1978). "Lindenmeier, 1934–1974: Concluding Report on Investigations". Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology. 24 (24). Washington, D.C.: 1–187. doi:10.5479/si.00810223.24.1.

- ^ Wheat, J.B. (1972). "The Olsen-Chubbuck site: a paleo-Indian bison kill". Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology 26.

- ^ Irwin, Henry J. and Cynthia C. Irwin (1966) Excavations at Magic Mountain: A Diachronic Study of Plains-Southwest Relations. Denver Museum of Natural History Proceedings Number 12. October 20, 1966.

- ^ "Peoples of the Mesa Verde Region: Archaic period: Overview". Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Gunnerson, James H. Archaeology of the High Plains. Denver: United States Forest Service, 1987. p. 28.

- ^ "Franktown Cave". National Register of Historic Places. February 1, 2006. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Cassells, E. Steve. (1997). The Archaeology of Colorado, Revised Edition. Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Books. pp. 320. ISBN 1-55566-193-9.

- ^ "Trinchera Cave Archeological District". National Register of Historic Places. October 22, 2001. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Excavations at Trinidad Reservoir". University of New Mexico. March 3, 2016. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Colorado Millennial Site". National Register of Historic Places. April 8, 1980. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Cordell, Linda S. Ancient Pueblo Peoples. St. Remy Press and Smithsonian Institution, 1994. ISBN 0-89599-038-5

- ^ "Ancestral Pueblo People of Mesa Verde". National Park Service. August 21, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "National Museum of the American Indian". Smithsonian Institution. 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Jicarilla Apache Nation". Jicarilla Apache Nation. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b The United States of America and the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara Nations (September 17, 1851). "Treaty of Fort Laramie, 1851" (PDF). Retrieved March 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b The United States of America and the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations (October 28, 1867). "Treaty between the United States of America and the Cheyenne and Arapahoe Tribes of Indians; Concluded October 28, 1867; Ratification advised July 25, 1868; Proclaimed August 19, 1868" (PDF). p. 593. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ The United States of America and the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota Nation, the Yanktonai band of the Dakota Nation, and the Northern band of the Arapaho Nation (April 29, 1868). "Treaty between the United States of America and different Tribes of Sioux Indians; Concluded April 29 et seq., 1868; Ratification advised February 16, 1869; Proclaimed February 24, 1869" (PDF). p. 635. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Northern Arapaho Tribe. "History of the Northern Arapaho Tribe". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Wind River Indian Reservation". 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes". Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Comanche Nation: About us". Comanche Nation. 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Kiowa Tribe". Kiowa Tribe. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Pawnee History". Pawnee Nation. 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ The United States of America and the Eastern Band of Shoshone and the Bannock Tribe (July 3, 1868). "Treaty between the United States of America and the Eastern Band of Shoshonees and the Bannack Tribe of Indians; Concluded, July 3, 1868; Ratification advised, February 16, 1869; Proclaimed, February 24, 1869" (PDF). p. 673. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b The United States of America and the Capote and Mouache Utes (December 30, 1849). "Treaty with the Utah". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b The United States of America and the Tabeguache Utes (October 7, 1863). "Treaty between the United States of America and the Tabeguache Band of Utah Indians, concluded October 7, 1863; Ratification advised, with Amendments, by the Senate, March 25, 1864; Amendments assented to, October 8, 1864; Proclaimed by the President of the United States, December 14, 1864" (PDF). p. 673. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Thirty-eighth United States Congress (May 5, 1864). "An Act to vacate and sell the present Indian Reservations in Utah Territory, and to settle the Indians of said Territory in the Uinta Valley" (PDF). p. 673. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Thirty-eighth United States Congress (February 23, 1865). "An Act to extinguish the Indian Title to Lands in the Territory of Utah suitable for agricultural and mineral Purposes" (PDF). p. 432. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The United States of America and the Ute Nation (March 2, 1868). "Treaty between the United States of America and the Tabeguache, Muache, Capote, Weeminuche, Tampa, Grand River, and Uintah Bands of Ute Indians" (PDF). Fortieth United States Congress. p. 619. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Forty-third United States Congress (April 29, 1874). "An act to ratify an agreement with certain Ute Indians in Colorado, and to make an appropriation for carrying out the same" (PDF). p. 36. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b United States of America and the Capote, Mouache, and Weeminuche Utes (November 9, 1878). "Agreement with the Capote, Muache, and Weeminuche Utes" (PDF). Pagosa Springs, Colorado. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b The United States of America and the Ute Nation (June 15, 1880). "An act to accept and ratify the agreement submitted by the confederated bands of Ute Indians in Colorado, for the sale of their reservation in said State, and for other purposes, and to make the necessary appropriations for carrying out the same" (PDF). Forty-sixth United States Congress. p. 199. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Forty-seventh United States Congress (July 28, 1882). "An act relating to lands in Colorado lately occupied by the Uncompahgre and White River Ute Indians" (PDF). p. 178. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ute Mountain Tribe (June 6, 1940). "Constitution and Bylaws of the Ute Mountain Tribe of the Ute Mountain Reservation in Colorado, New Mexico, Utah". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Southern Ute Indian Tribe (2022). "History of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Weeminuche Band of Ute Nation". Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Christopher Columbus. "The Log of Christopher Columbus". Translated by John Boyd Thacher. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Pope Alexander VI (May 4, 1493). "Inter Caetera". Papal Encyclicals Online. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ The Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Empire (June 7, 1494). "The Treaty of Tordesillas". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Sosa, Juan B. and Arce, Enrique J. (October 1911). "Compendio de Historia de Panamá" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2006. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hernán Cortés (April 12, 1866). "Cartas y relaciones de Hernán Cortés al emperador Carlos V" (in Spanish). Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Louis XV of France and Carlos III of Spain (September 30, 1764). "Treaty of Fontainebleau 1762 - English Transcript". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b The French Republic and Carlos IV of Spain (October 1, 1800). "Preliminary and Secret Treaty between the French Republic and His Catholic Majesty the King of Spain, Concerning the Aggrandizement of His Royal Highness the Infant Duke of Parma in Italy and the Retrocession of Louisiana". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Elizabeth Wormeley Latimer (1897). "Spain in the Nineteenth Century". Chicago, A. C. McClurg & company. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Binger Hermann (1898). "The Louisiana Purchase". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b The United States of America and the United Mexican States (January 12, 1828). "Treaty of Limits between the United States of America and the United Mexican States" (PDF). p. 372. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b The United States of America and the United Mexican States (April 5, 1831). "Additional Article to the Treaty of Limits concluded between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, on the 12th day of January, 1828" (PDF). p. 376. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c Twenty-ninth United States Congress (December 29, 1845). "Joint resolution for the admission of the State of Texas into the Union" (PDF). p. 108. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Twenty-ninth United States Congress (April 25, 1846). "An act providing for the prosecution of the existing war between the United States and the Republic of Mexico" (PDF). p. 9. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Dwight L. Clarke (1961). "Stephen Watts Kearny, Soldier of the West". Norman, University of Oklahoma Press [1961]. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Eighth United States Congress (October 21, 1803). "An Act to enable the President of the United States to take possession Oct. 31, 1803, of the territories ceded by France to the United States, by the treaty concluded at Paris, on the thirtieth of April last; and for the temporary government thereof" (PDF). p. 245. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Eighth United States Congress (March 26, 1804). "An Act erecting Louisiana into two territories, and providing for the temporary government thereof" (PDF). p. 283. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Eighth United States Congress (March 3, 1805). "An Act further providing for the government of the district of Louisiana" (PDF). p. 331. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Twelfth United States Congress (June 4, 1812). "An Act providing for the government of the territory of Missouri" (PDF). p. 743. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Sixteenth United States Congress (March 6, 1820). "An Act to authorize the people of the Missouri territory to form a constitution and state government, and for the admission of such state into the Union on an equal footing with the original states, and to prohibit slavery in certain territories" (PDF). p. 545. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ James Monroe (August 10, 1821). "Proclamation 28—Admitting Missouri to the Union". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Peter Crawley (October 1, 1989). "The Constitution of the State of Deseret". BYU Scholars Archive. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Thirty-first United States Congress (September 9, 1850). "An Act proposing to the State of Texas the Establishment of her Northern and Western Boundaries, the Relinquishment by the said State of all Territory claimed by her exterior to said Boundaries, and of all her Claims upon the United States, and to establish a territorial Government for New Mexico" (PDF). p. 446. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Thirty-first United States Congress (September 9, 1850). "An Act for the admission of the State of California into the Union" (PDF). p. 452. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Thirty-first United States Congress (September 9, 1850). "An Act to establish a Territorial Government for Utah" (PDF). p. 453. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Thirty-third United States Congress (May 30, 1854). "An Act to Organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas" (PDF). p. 277. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Constitution of Jefferson Territory" (PDF). Colorado Magazine. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ General Assembly of the Territory of Jefferson (November 28, 1859). "Provisional Laws and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of Jefferson Territory". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Thirty-sixth United States Congress (January 29, 1861). "An Act for the Admission of Kansas into the Union" (PDF). p. 126. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Forty-third United States Congress (March 3, 1875). "An act to enable the people of Colorado to form a constitution and State government, and for the admission of the said State into the Union on an equal footing with the original States" (PDF). p. 474. Retrieved March 16, 2022.