Teodora Alonso Realonda

Teodora Alonso Realonda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Teodora Alonso Realonda y Quintos November 9, 1827 |

| Died | August 16, 1911 (aged 84) |

| Resting place | Rizal Shrine, Calamba, Laguna |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 11 (including Saturnina, Paciano, Trinidad, and José) |

Teodora Alonso Realonda y Quintos (November 9, 1827 – August 16, 1911) was a wealthy woman in the Spanish colonial Philippines. She was best known as the mother of the Philippines' national hero Jose Rizal. Realonda was born in Santa Cruz, Manila. She was also known for being a disciplinarian and hard-working mother. Her medical condition inspired Rizal to take up medicine.[1][2]

Early life

[edit]

Teodora Alonso was the second child of Lorenzo Alberto Alonso, a municipal captain in Biñan, Laguna, and Brijida de Quintos. Her family had adopted additional surname Realonda in 1849, after Governor General Narciso Clavería y Zaldúa decreed the adoption of Spanish surnames among the Filipinos for census purposes (though they already had Spanish names).

Teodora's ancestry included Chinese, Japanese, and Tagalog. Her lineage can be traced to the affluent Florentina family of Chinese mestizo families originating in Baliuag, Bulacan.[3] She also had Spanish ancestry from both of her parents.[4] Her maternal grandmother, Regina Ochoa, had mixed Spanish, Chinese ancestry as well as ancestry from Pangasinan and Tagalog regions.

Teodora Alonso was also a representative in the Spanish Courts and a pious Catholic, being a Knight of the Order of Isabella.[2] Quintos was an educated woman, who became a housewife, devoted to caring for her family's needs. Realonda came from a financially able family and studied at the Colegio de Santa Rosa in Manila, just like her mother who was well-bred and had an educational background in the subjects of mathematics and literature.[2]

Personal life

[edit]This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (January 2024) |

Teodora married Francisco Mercado, a native of Biñan, Laguna, on June 28, 1848, when she was 20 years old.[5] The couple resided in Laguna, particularly in Calamba and built a business from agriculture. She was an industrious and educated woman, managing the family's farm and finances. Teodora used her knowledge to grow the rice, corn, and sugarcane that sustained the family's well-to-do lifestyle. She also expanded the family business into the areas of textiles, flour, and sugar milling, refining these raw materials and selling the finished staples from a small store on the ground floor of the family home.[2][6]

Teodora had eleven children with Francisco. They are Saturnina, Paciano, Narcisa, Olympia, Lucia, Maria, José, Concepcion, Josefa, Trinidad and Soledad. All her children were sent to study in different colleges in Manila, but only José was sent to Europe as he was inspired to study medicine, particularly ophthalmology, to help his mother due to her failing eyesight.

José honored his mother in Memoirs of a Student in Manila, writing, "After God, the mother is everything to man."[7]

Teodora’s half-brother, Jose Alberto, wanted to divorce his wife, whom he alleged to be having an affair with another man. Teodora persuaded him to put up with her and preserve their marriage. Since then Jose Alberto went often to Calamba to seek advice from Teodora. This was learned by his wife who then suspected Jose Alberto and Teodora plotting something evil to her. Later Jose’s wife and an officer of the Guardia Civil (presumably the same one who was refused horse fodder) then accused Jose Alberto and Teodora of trying to poison Jose Alberto’s wife. Teodora was named as an accomplice to Jose Alberto, the main suspect. Quick like a bolt of lightning, Teodora was hauled to jail by the mayor, Antonio Vivencio del Rosario, a known yes-man of the friars. A judge who did not like the way he was treated at the Mercado-Rizal house, ordered that Teodora be imprisoned in Santa Cruz, the capital of the province. She was made to walk the distance, though usual travel was by boat. She was forbidden to use any vehicle, although her family was willing to pay for it and include her escorts for the ride. She was to suffer humiliation and hardship as prescribed by those her family had offended. On the first night of the journey to Santa Cruz, Teodora and her escorts came to a village where there was a festival. Teodora was recognized and invited by one of the prominent families. The judge, upon learning that Teodora was honored in the village, was enraged. He went to the house she visited. There was a guard there and the judge knocked and broke his cane on the poor man’s head then beat up the owner of the house. This obvious case of prejudice was reported by Teodora’s lawyers. The Supreme Court decided to set her free. The cruel judge respected the decision but then charged Teodora with contempt of court. To this, the Supreme Court was persuaded but since Teodora’s wait in prison was longer than the sentence, ordered her release. Then the lawyer of Jose Alberto charged Teodora with theft. There was rumor that Teodora borrowed money from her brother. The lawyer obviously was interested in recovering the money for himself. This case was heard but dismissed by the court. Teodora was coerced to make a plea of guilt of which she was promised a pardon, immediate freedom and reunion with her family. It as all for naught. Teodora finally regained freedom after two and a half years, as ordered by none other than the Governor General, who was charmed one fiesta day in Laguna by a daring little girl. So charmed was he that he asked the little girl what she would like him to give her. "My mother", was the reply. The little girl was Soledad, Teodora’s youngest daughter. A quick inquiry, a quick decision, a new trial ended in Teodora’s acquittal.[8]

After Rizal's death

[edit]In August 1898, Narcisa got the body of her brother Rizal, and found out that the body was not even laid out in a coffin. Because of this, the government offered Teodora a lifetime pension as a token of gratitude, after Rizal was declared the national hero of the Philippines. However, she declined the offer, as she said that her family "has never been patriotic for money."[9] She even saw the declaration of the monument for Rizal a week before she died. Alonso died in her home at 478 San Fernando Street, San Nicolas, Manila on August 16, 1911.[1][10][11] Her remains were interred at a mausoleum in Cementerio del Norte, Manila, joining that of her husband Francisco, before being transferred to their current tomb at Rizal Shrine in Calamba, Laguna.[12]

-

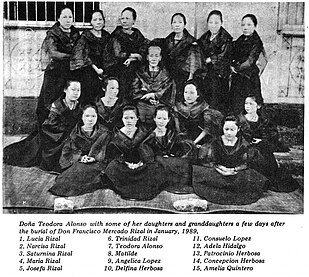

Alonso, with her daughters and granddaughters, a few days after the burial of Francisco Mercado

-

Historical markers in Tagalog marking the former site of the house at 478 San Fernando Street in San Nicolas, Manila where Alonso died

-

Historical marker marking the original tomb of Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonso at the Manila North Cemetery

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Teodora de Quintos Alonso". Geni.com. 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Today in Philippine History, November 9, 1827, Teodora Alonso, mother of Dr. Jose Rizal was born in Meisik, Tondo, Manila". The Kahimyang Project. 6 November 2012.

- ^ Austin Craig (January 8, 2005). The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lineage, Life and Labors of Jose Rizal: Philippine Patriot. Retrieved July 1, 2016 – via www.gutenberg.org.

- ^ ""Lola Lolay of Bahay na Bato" | OurHappySchool". ourhappyschool.com.

- ^ "Today in Philippine History, June 28, 1848, Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonso got married". The Kahimyang Project. 22 May 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ "Filipinas Heritage Library | Doña Teodora". www.filipinaslibrary.org.ph. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ Medina, Marielle (November 10, 2014). "Did you know: Teodora Alonso". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- ^ Uckung, Peter Jaynul V. (2012-09-04). "Teodora Alonso's Trail of Tears - National Historical Commission of the Philippines". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ Limos, Mario Alvaro (August 16, 2019). "Teodora Alonzo Was a Woman of Steel". Esquire Magazine. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ^ de Gamoneda, Francisco J. (1898). Plano de Manila y sus Arrables [Map of Manila and its suburbs] (Map). 1:10,000 (in Spanish). Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ "Ang Tahanan ng Kaanak ni Rizal 1903 Daang San Fernando, Maynila". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ "Our Heritage and the Departed: A Cemeteries Tour". Malacañang Palace. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2017.