Teacher retention

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2023) |

Teacher retention is a field of education research that focuses on how factors such as school characteristics and teacher demographics affect whether teachers stay in their schools, move to different schools, or leave the profession before retirement. The field developed in response to a perceived shortage in the education labor market in the 1990s. The most recent meta-analysis establishes that school factors, teacher factors, and external and policy factors are key factors that influence teacher attrition and retention.[1] Teacher attrition is thought to be higher in low income schools and in high need subjects like math, science, and special education. More recent evidence suggests that school organizational characteristics has significant effects on teacher decisions to stay or leave.[2]

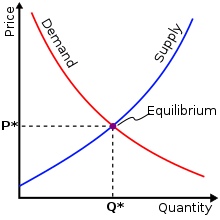

Teacher shortage can be caused both by decreased teacher retention and decreased teacher supply.[3] The teacher supply depends on wage elasticity.[4]

Factors

[edit]Schools

[edit]Researchers and policy makers have identified some commonalities across schools and districts that affect teacher retention.[5][6] Some school factors are "push" factors that push teachers to leave their current school or the profession. Other school factors are "pull" factors that encourage teachers to stay in their current school. Teacher attrition and retention also vary based on the sector of the school (e.g., traditional public vs. charter) and whether it is located in an urban or rural area.[7][8] The characteristics of teacher, schools, and students can even redefine the effect of salaries on teacher retention. [9][10]

Push factors

[edit]Certain factors are linked to teachers leaving schools or leaving the profession before retirement. Researchers have used data from school districts and national surveys of teachers and schools to demonstrate that there are common factors that push teachers to either leave their schools or leave the profession. The most significant factors include low salary, student behavior issues, lack of support from school administration, and inability to participate in decision-making.[5] Teachers may also be more likely to leave if they are resistant to using prescribed curriculums or are discouraged from modifying their instruction.[11] Over time, individual school environments affect teacher attrition more than district measures like teacher salary, student demographics, or urban settings.[12]

Pull factors

[edit]Other factors encourage teachers to stay at their current school. Teachers are more likely to stay in elementary schools than middle or high schools.[6] Teachers who earn at least $40,000 per year are most likely to stay through their fifth year at the same school.[6] Teachers stay longer in schools that have missions in alignment with the teacher's personal mission.[13] One of the most successful strategies used to retain teachers includes mentoring and teacher teaming.[14] Others point to the importance of teachers being treated as professionals who are trusted and collaborate with one another to meet student needs.[15] These professional practices can include individuality, creativity, high expectations for students, and community building with mentors or peers.[11] Teachers are also more likely to stay when they report being satisfied with their school.[6] School location and student demographics are not major factors in either pushing teachers away or pulling them in.

Teacher factors

[edit]Researchers and policy makers have also collected information about teacher demographics to better understand teachers' choices to stay or leave their schools. Most studies include research on teacher age, experience, and gender as well as teacher qualifications.

Age, experience, and gender

[edit]Teachers are most likely to stay in their schools if they are between the ages of 30–50.[5] Teachers under 30 are more likely to move schools within districts, move districts, or move to other states to teach. Younger teachers often still have preliminary credentials which allows them more flexibility within states as states often have their own standardized licensure and testing requirements that discourage teachers from moving. Younger teachers are also less likely to be vested in their pension systems and more likely to move districts before choosing a district which may offer a higher salary or better benefits and retirement options.[16] Relatedly, novice teachers are more likely to turn over than more experienced teachers, particularly when they work in traditionally disadvantaged schools.[17]

Salary increases can draw younger teachers to particular districts with the promise of higher payment for teaching in the long term.[18] The relationship between life cycle events such as marriage or having children and teacher attrition can be difficult to measure, but teachers who leave the profession are more likely to have recently had children.[19] Teachers with children under 5 are increasingly likely to leave the profession. Gender also plays a role in this trend: young female teachers are more likely than young male teachers to leave.[12] Women who leave the profession are also more likely to return to teaching than men.[6] Teachers over 50 are also more likely to leave the profession, but this is generally explained by teachers who are closer to retirement.

Qualifications

[edit]Researchers are examining teacher preparation in relation to retention, including the quality of higher education curriculum and student teaching experiences. Mentorships and inductions have been shown to help early-career teachers and other educators adapt and stay in the job.[20] Teachers with better academic qualifications including grades, test scores, graduate degrees, and undergraduate college selectivity are more likely to leave the profession. There is no major retention difference between teachers who completed traditional preparation programs and teachers who completed alternative certification programs, like Teach for America.[12] Teachers are more likely to stay when students are high achieving.[21]

Teachers with certain teaching qualifications and teaching assignments are more likely to leave their schools or the profession. Special education teachers are not more likely to leave teaching, but they are more likely to transfer to positions as general educators.[22] Elementary teachers are more likely to stay than middle and high school teachers. Teacher who feel effective in their jobs are also more likely to continue teaching.[23]

External and policy factors

[edit]This is a new area of research that examines how policy factors and factors beyond school and teacher correlates influence teacher attrition and retention. This is an increasingly important strand of research linking how external policies such as accountability and evaluation may affect turnover. The policies are evolving to address specific needs in various educational contexts. For instance, many accountability-based policies such as merit pay, retention bonuses, and teacher evaluation aim to change the teacher composition in school.[1] A more recent approach provides districts with flexible financial support to create targeted strategies locally, moving away from "one-size-fits-all" policies. This flexibility allows for more customized solutions based on specific district needs. [24]

Retaining teachers of color

[edit]Retaining teachers of color is an important element of teacher retention. Students of color perform better with race congruent teachers of color[25] and American students are increasingly non white. In 2014 50.3% of American public school students were Latino, Asian, and African-American with demographic data suggesting that the percentage of students of color will continue to grow.[26] Some evidence suggests that teachers of color have higher attrition rates than white teachers and other evidence suggests the opposite.[12]

Teachers of color are more likely to stay in a school in which they are led and supervised by administrators of color. Overall, 84% of white teachers have a race matched principal while only 44% of Black teachers have a race matched principal and 8% of other races have a matched principal. Teachers with a race matched principal are more likely to report earning additional pay, feeling autonomy, and experiencing additional support, all of which are linked to overall teacher retention. Race matched teachers are also more likely to report being satisfied with their jobs.[6][27] Race matching also affects exits from the profession more than transfers to another school. Also, white men are more likely to leave the profession when there are more students of color. In contrast, teachers of color have higher exit rates overall but are less likely to leave when they have more non white students.[18]

Retaining effective teachers

[edit]Federal policy initiatives during the Obama Administration have emphasized the importance of retaining effective teachers, rather than just working to retain all teachers. This is partly due to President Obama and the United States Department of Education’s Race to the Top initiative which granted money to states pledging to institute policies which retained and released teachers based in part on their evaluations.[28] The measurement of teacher success is often based on “value added” determinations based on student standardized test scores. Value-added measurements assess the effect of a teacher on student test scores by quantifying teacher ability. These measurements are seen by some as “noisy” and only partly a measure of teacher performance, but still useful.[29] The American Education Research Association cautions against using value added models in most situations due to scientific and technical limitations.[30]

The Race to the Top incentives represented a major shift in how districts and administrators evaluated and retained teachers. Prior to Race to the Top, teacher effectiveness had been determined by years of experience and years of graduate study. Now, in many states, value added modeling is used alongside principal evaluations of teacher observations and teacher progress on student learning outcomes. One controversial use of value-added teacher evaluation was in Washington D.C. under the leadership of Michelle Rhee.[25] The D.C. program was unique in rewarding high performing teachers with higher salaries and bonus pay while also threatening to dismiss low performing teachers. Teachers in D.C. under threat of dismissal made greater gains in their teaching practice than teachers who stood to gain financially. The dismissal threat also increased voluntary attrition of lower performing teachers by 50%.[25] Statistics suggest that having a top performing teacher rather than a low performing teacher “four years in a row would be enough to close the black-white test score gap.”[28]

Teacher effectiveness has also been linked to how often teachers move schools. Overall, leavers are less effective than movers. More effective teachers are more likely to stay in the same schools, unless they being their careers in lower performing schools.[21] Teachers with low performing students are more likely to leave their schools in the first 1–2 years. Low performing teachers are more likely to move to schools that are similar to the schools they currently teach in, while higher performing teachers will move from low performing schools to higher performing schools.[21] This evidence indicates that some teacher attrition may be beneficial to students.

Retention of Early Career Teachers

[edit]The most comprehensive nationally-representative study on early career teachers in the United States is a study that examines early career teachers using the Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS) and its supplement, the Teacher Follow-Up Survey (TFS) from 1987-88 to 2011-2012.[17] The authors find that novice teachers are more likely to be certified than before and they are more likely to begin their careers in schools with more racially and ethnically diverse students. While they do turn over more frequently than more experienced teachers, supportive colleagues and administrators as well as induction supports are associated with lowering attrition rates.[17]

A Canada-wide survey revealed that most cases of teacher attrition occur within the first five years of teaching, with 50% of cases occurring within the first two years.[31] It is therefore important to consider a) the factors that lead to early career teacher attrition and b) viable interventions that aim to retain beginning teachers.

One study found factors that contribute to early career teacher attrition to include: a difficulty with balancing work and home life and the time constraints involved, issues in classroom management and students' challenging behaviours, strained relationships with parents, staff and/or administration, and feeling incompetent in one's role as a teacher.[31] Another study considered teacher perceptions' of the workplace environment, and how these perceptions play a role in motivating teachers to stay or leave their current positions.[32] School climates that were perceived to be nurturing were characterized as open to both collaboration and differences in instructional preferences, uplifting, and supportive.[32] When aspects of this environment were perceived to be missing, teachers more often noted their negative experiences in the workplace environment.[32] An Australian study suggested that decisions to leave the profession are influenced by the quality of mentoring and induction programs in a school, as well as relationships with other teachers and school leadership.[33]

Organizational-level interventions aimed to retain early career teachers can involve the monitoring of workload amounts, mentorship programs that help early career teachers create a better work-life balance, guidance from administration and/or mentors in navigating the specific socio-cultural environment of the school, mentor modeling of effective teaching practices, and providing feedback on teaching practices.[34] It is also important to consider interventions at the individual-level. One might investigate how early career teachers in remote schools manage negative aspects of their workplace environment. One study noted that in the absence of professional or organizational supports, teachers may still develop resilience by relying on "personal" supports, such as relationships with family and friends and the construction of a teaching identity.[35] Future research in the area of the retention of early career teachers may therefore look at how the construction of a teaching identity affects one's likelihood to stay or leave his or her teaching post.

Conceptual Frameworks of Teacher Attrition and Retention

[edit]There are few comprehensive conceptual frameworks of teacher attrition and retention since individual studies present their specific framework to focus on a narrow range of factors within their own study. However, a systematic review of the empirical international literature has established a comprehensive conceptual framework of teacher attrition and retention. Synthesizing nearly 160 studies from forty years of research on teacher turnover, the authors organize the determinants of teacher attrition and retention into nine categories grouped into personal correlates, school correlates, and external correlates.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Nguyen, Tuan D.; Pham, Lam D.; Crouch, Michael; Springer, Matthew G. (November 2020). "The correlates of teacher turnover: An updated and expanded Meta-analysis of the literature". Educational Research Review. 31: 100355. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100355. S2CID 224967353.

- ^ Nguyen, Tuan D. (January 2021). "Linking school organizational characteristics and teacher retention: Evidence from repeated cross-sectional national data". Teaching and Teacher Education. 97: 103220. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2020.103220. S2CID 226316946.

- ^ Sutcher, Leib; Darling-Hammond, Linda; Carver-Thomas, Desiree (September 2016). A Coming Crisis in Teaching? Teacher Supply, Demand, and Shortages in the U.S. (Report). Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved 20 July 2024.[page needed]

- ^ Wolter, Stefan C.; Denzler, Stefan (2004). "Wage Elasticity of the Teacher Supply in Switzerland". Brussels Economic Review. 47 (3): 387–408. SSRN 391984.

- ^ a b c Ingersoll, Richard M. (January 2001). "Teacher Turnover and Teacher Shortages: An Organizational Analysis". American Educational Research Journal. 38 (3): 499–534. doi:10.3102/00028312038003499. S2CID 8630217.

- ^ a b c d e f Raue, Kimberley; Gray, Lucinda (September 2015). "Career Paths of Beginning Public School Teachers: Results from the First through Fifth Waves of the 2007-08 Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study. Stats in Brief. NCES 2015-196". S2CID 147732128. ERIC ED560730.

- ^ Crouch, Michael; Nguyen, Tuan D. (3 April 2021). "Examining Teacher Characteristics, School Conditions, and Attrition Rates at the Intersection of School Choice and Rural Education". Journal of School Choice. 15 (2): 268–294. doi:10.1080/15582159.2020.1736478. S2CID 216441377.

- ^ Nguyen, Tuan D. (July 2020). "Examining the Teacher Labor Market in Different Rural Contexts: Variations by Urbanicity and Rural States". AERA Open. 6 (4). doi:10.1177/2332858420966336. S2CID 226338013.

- ^ Babaei Balderlou, Saharnaz (2023). "Protecting the Rainbows: Teacher Retention and Employment Anti-Discrimination Policies in the U.S." SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4633258. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ Tran, Henry; Babaei-Balderlou, Saharnaz; Vesely, Randall S. (2024-12-01). "Balancing the scale: Investigating the effect of frontloading and backloading salary structures on teacher turnover". Teaching and Teacher Education. 152: 104809. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2024.104809. ISSN 0742-051X.

- ^ a b Achinstein, Betty; Ogawa, Rodney (1 April 2006). "(In)Fidelity: What the Resistance of New Teachers Reveals about Professional Principles and Prescriptive Educational Policies". Harvard Educational Review. 76 (1): 30–63. doi:10.17763/haer.76.1.e14543458r811864. OCLC 425073080. INIST 17647331 ProQuest 212261339.

- ^ a b c d DeAngelis, Karen J.; Presley, Jennifer B. (September 2011). "Toward a More Nuanced Understanding of New Teacher Attrition". Education and Urban Society. 43 (5): 598–626. doi:10.1177/0013124510380724. S2CID 145466479.

- ^ Egalite, Anna J.; Jensen, Laura I.; Stewart, Thomas; Wolf, Patrick J. (2 January 2014). "Finding the Right Fit: Recruiting and Retaining Teachers in Milwaukee Choice Schools". Journal of School Choice. 8 (1): 113–140. doi:10.1080/15582159.2014.875418. S2CID 144042584.

- ^ Ingersoll, Richard; Smith, Thomas (May 2003). "The Wrong Solution to the Teacher Shortage". Educational Leadership. 60 (8): 30–33. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.182.106.

- ^ Cochran-Smith, Marilyn (November 2004). "Stayers, Leavers, Lovers, and Dreamers: Insights about Teacher Retention". Journal of Teacher Education. 55 (5): 387–392. doi:10.1177/0022487104270188. S2CID 145058509.

- ^ Goldhaber, Dan; Grout, Cyrus; Holden, Kristian L.; Brown, Nate (1 November 2015). "Crossing the Border? Exploring the Cross-State Mobility of the Teacher Workforce". Educational Researcher. 44 (8): 421–431. doi:10.3102/0013189X15613981. S2CID 147626898.

- ^ a b c Redding, Christopher; Nguyen, Tuan D. (July 2020). "Recent Trends in the Characteristics of New Teachers, the Schools in Which They Teach, and Their Turnover Rates". Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education. 122 (7): 1–36. doi:10.1177/016146812012200711. S2CID 238748068.

- ^ a b Imazeki, Jennifer (August 2005). "Teacher salaries and teacher attrition". Economics of Education Review. 24 (4): 431–449. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.07.014.

- ^ Boe, Erling E.; Bobbitt, Sharon A.; Cook, Lynne H.; Whitener, Summer D.; Weber, Anita L. (January 1997). "Why Didst Thou Go? Predictors of Retention, Transfer, and Attrition of Special and General Education Teachers from a National Perspective" (PDF). The Journal of Special Education. 30 (4): 390–411. doi:10.1177/002246699703000403. S2CID 145498710.

- ^ "The Educator Pipeline: Turnover, Fewer Applicants Will Impact Student Achievement" (PDF). Learning First Alliance. 2016.

- ^ a b c Boyd, Donald; Grossman, Pamela; Lankford, Hamilton; Loeb, Susanna; Wyckoff, James (March 2009). "'Who Leaves?' Teacher Attrition and Student Achievement". ERIC ED508275.

- ^ Boe, Erling E.; Bobbitt, Sharon A.; Cook, Lynne H. (January 1997). "Whither Didst Thou Go? Retention, Reassignment, Migration, and Attrition of Special and General Education Teachers from a National Perspective". The Journal of Special Education. 30 (4): 371–389. doi:10.1177/002246699703000402. S2CID 143107656.

- ^ Hughes, Gail D. (June 2012). "Teacher Retention: Teacher Characteristics, School Characteristics, Organizational Characteristics, and Teacher Efficacy". The Journal of Educational Research. 105 (4): 245–255. doi:10.1080/00220671.2011.584922. S2CID 145201429.

- ^ Tran, Henry; Babaei-Balderlou, Saharnaz; Smith, Douglas A (2022-10-27). "The promises and pitfalls of government-funded teacher staffing initiatives on teacher employment in hard-to-staff schools: Evidence from South Carolina". Policy Futures in Education. 22: 43–65. doi:10.1177/14782103221135891. ISSN 1478-2103. S2CID 253189668.

- ^ a b c Dee, Thomas S.; Wyckoff, James (March 2015). "Incentives, Selection, and Teacher Performance: Evidence from IMPACT: Incentives, Selection, and Teacher Performance" (PDF). Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 34 (2): 267–297. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.593.8357. doi:10.1002/pam.21818. JSTOR 43866371. SSRN 2342009.

- ^ "Table 203.50. Enrollment and percentage distribution of enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by race/ethnicity and region: Selected years, fall 1995 through fall 2023". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ^ Grissom, Jason A.; Keiser, Lael R. (2011). "A supervisor like me: Race, representation, and the satisfaction and turnover decisions of public sector employees". Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 30 (3): 557–580. doi:10.1002/pam.20579. JSTOR 23018964. OCLC 5152406559.

- ^ a b Green, Elizabeth (2015). Building a Better Teacher. W.W. Norton & Company.

- ^ Winters, Marcus A.; Cowen, Joshua M. (August 2013). "Who Would Stay, Who Would Be Dismissed? An Empirical Consideration of Value-Added Teacher Retention Policies". Educational Researcher. 42 (6): 330–337. doi:10.3102/0013189X13496145. S2CID 144827731.

- ^ "AERA Issues Statement on the Use of Value-Added Models in Evaluation of Educators and Educator Preparation Programs" (Press release). American Educational Research Association. 11 November 2015.

- ^ a b Karsenti, Thierry; Collin, Simon (2013). "Why are New Teachers Leaving the Profession? Results of a Canada-Wide Survey". Education. 3 (3): 141–149. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.668.252.

- ^ a b c Schuck, Sandy; Aubusson, Peter; Buchanan, John; Varadharajan, Meera; Burke, Paul F. (15 March 2018). "The experiences of early career teachers: new initiatives and old problems". Professional Development in Education. 44 (2): 209–221. doi:10.1080/19415257.2016.1274268. hdl:10453/77021. S2CID 151642600.

- ^ Kelly, Nick; Cespedes, Marcela; Clara, Marc; Hanaher, Patrick (March 2019). "Early career teachers' intentions to leave the profession: The complex relationships among preservice education, early career support, and job satisfaction". Australian Journal of Teacher Education. 44 (3): 93–113. doi:10.14221/ajte.2018v44n3.6.

- ^ Hudson, Peter (1 July 2012). "How Can Schools Support Beginning Teachers? A Call for Timely Induction and Mentoring for Effective Teaching". Australian Journal of Teacher Education. 37 (7). doi:10.14221/ajte.2012v37n7.1. ERIC EJ995200.

- ^ Sullivan, Anna; Johnson, Bruce (2012). "Questionable practices?: Relying on individual teacher resilience in remote schools". Australian and International Journal of Rural Education. 22 (3): 101–116. doi:10.47381/aijre.v22i3.624. S2CID 142157368. Gale A327989291.

- ^ Nguyen, Tuan D.; Springer, Matthew G. (13 July 2021). "A conceptual framework of teacher turnover: a systematic review of the empirical international literature and insights from the employee turnover literature". Educational Review. 75 (5): 993–1028. doi:10.1080/00131911.2021.1940103. S2CID 237790964.