Talk:Solar System/Archive 5

| This is an archive of past discussions about Solar System. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

| Archive 1 | ← | Archive 3 | Archive 4 | Archive 5 | Archive 6 | Archive 7 | → | Archive 10 |

Lead needs to be rewritten

Pursuant to the FAR for this article, I believe the lead needs to be rewritten. In its current state, I don't think the article is a "concise overview of the entire article", rather it's a

Change "the" to "our" in the lead?

"The Solar System", even with the latter two words capitalized, is ambiguous in that it could mean any general "solar system"; a system with a star. But since this generic label is indeed the actual proper term for our own solar system, should we not at least open with "Our Solar System"? Thoughts?. — `CRAZY`(lN)`SANE` 06:58, 27 April 2009 (UTC)

- There is no official "generic" term for "Solar System". There is only one Solar System, so there is no need to specify that it is "our" Solar System. Serendipodous 08:52, 27 April 2009 (UTC)

- There is only one solar system since SOL means the Sun. But there are other star systems and planetary systems. The Sun is the center of the solar system and the giver of life. -- Kheider (talk) 09:24, 27 April 2009 (UTC)

- I think we should stay away from using the possessive "our" when describing astronomical objects. First, it implies ownership; second the language seems less encyclopedic, and third because applying "solar systems" to stellar planetary systems other than the Sun's is improper.—RJH (talk) 19:16, 27 April 2009 (UTC)

- Agreed, but I've even heard astronomers let "solar system" slip when talking of exoplanetary systems. So it might not be that big a deal. Most seem to use either "star system" or "stellar system" when discussing exoplanets. My take on the "Our Solar System" idea is that "The" gives more emphasis (oomph) than "Our", which sounds a bit wishy-washy (as in "Our li'l kitty-cat Solar System"). .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 04:43, 28 April 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, I've seen that happen as well. Still, I think it's good practice to be a little more precise in word usage for the purposes of an encyclopedia than it might be in casual discussions.—RJH (talk) 21:00, 28 April 2009 (UTC)

- Agreed, but I've even heard astronomers let "solar system" slip when talking of exoplanetary systems. So it might not be that big a deal. Most seem to use either "star system" or "stellar system" when discussing exoplanets. My take on the "Our Solar System" idea is that "The" gives more emphasis (oomph) than "Our", which sounds a bit wishy-washy (as in "Our li'l kitty-cat Solar System"). .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 04:43, 28 April 2009 (UTC)

- The

Is a proper way to put it.

- Our

I think it belongs to life on Earth. Who else is entitled to claim possession of it?

- Relax

Either way works!

- Style

The start of the article should be properly proper, as it were. Later in the article usage can be relaxed! HarryAlffa (talk) 13:37, 28 April 2009 (UTC)

Layout and images

I've made a few tweaks to image layout - hope no-one minds. Could someone add a footnote to this image? I have absolutely no idea what it shows and the article doesn't seem to mention it either. Thanks Smartse (talk) 13:10, 3 May 2009 (UTC)

- The present caption looks okay, and readers can click on the image for details. There is another similar image just above this one on the left. Are both really needed? If I had to choose which to stay, I would opt for this one. .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 21:58, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Gas, Ice, Rock

The reference about gases, ices and rock was added in some haste during a previous dispute with HarryAlffa, and I can't remember who added it or where he got the information from. If that person could come back and say where he got it I would be very grateful. Serendipodous 11:49, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

- I only added information about ices, you added information about rock (which was wrong), and ASHill included gases. Referring to melting points instead of boiling points is unique, therefore highly questionable. To mix both is just plain dumb, it's not self-consistent, I corrected that again recently, but someone reverted it. HarryAlffa (talk) 15:32, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

- Under no circumstances this classification can be based on boiling points. This is simply meaningless. Boiling points strongly depend on pressure, while melting points do not. What pressure do you assume, when you talk about boiling points? In the vacuum the liquid phase does not exist at all, so, what are you going to boil? Ruslik (talk) 15:51, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

- I've fixed the inconsistency. This issue needs to be resolved somehow. It can't simply be deleted, because the Solar System article, and indeed all Solar System articles, use these terms continuously, precisely because the scientific papers we rely on for sourcing use these terms continuously. It might be that the IAU has no say in this issue, and that these terms are established by geologists. It might also be that there is no established definition for these terms, and we're just going to have to muddle through, like we do with terms like "asteroid" and "other solar systems". Serendipodous 17:16, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

- Under no circumstances this classification can be based on boiling points. This is simply meaningless. Boiling points strongly depend on pressure, while melting points do not. What pressure do you assume, when you talk about boiling points? In the vacuum the liquid phase does not exist at all, so, what are you going to boil? Ruslik (talk) 15:51, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

- Talking about the melting point of H and He just grates. The diagram shows melting point & boiling point varies with pressure. Maybe standard pressure is what Planetary Science Research Discoveries presumes when defining volatiles using boiling point. HarryAlffa (talk) 18:23, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

this astronomy page suggests that the terms "gas" "ice" and "rock" are shorthand for specific compounds. Hydrogen and helium are gas, water and ammonia are ice, and silicates are rock. Serendipodous 22:18, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

Wow. And once again, Ruslik comes in with a source. Well that's sorted. :-) Serendipodous 13:45, 17 May 2009 (UTC)

Plasma

I was reading the recent edit that changed "atomic hydrogen" to "molecular hydrogen", and it made me wonder... should hydrogen plasma also be mentioned in this section? It is the plasma of the Solar wind that is present. Is it too small an amount to be mentioned? .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 19:12, 17 May 2009 (UTC)

- The solar wind is mentioned later on, so I don't think it needs to be mentioned there. Besides I don't think the solar wind really qualifies as "hydrogen", since it's mostly (I think) just protons and electrons.Serendipodous 21:23, 17 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, protons and electrons make up the Solar wind. It's in plasma form, though, the "fourth state of matter". So if I'm not mistaken, the plasma of the Solar wind is ionized hydrogen. I'm not sure, though, what the concentration is. Only that it spreads out beyond the planets to form the "heliosphere", a plasma bubble around the Solar system. The paragraph in which the recent edit occurred begins, "Planetary scientists use the terms gas, ice, and rock to describe the various classes of substances found throughout the Solar System." I'm just wondering if this would be improved by making it read ". . . use the terms gas, ice, rock and plasma to describe . . .", and then like the others, just a very brief explanation about plasma? It would need an expert's fine tuning, which unfortunately, I am not. .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 04:15, 18 May 2009 (UTC)

- Plasma is a formal scientific state of matter, alongside solid, liquid and gas. The terms gas, ice and rock are largely informal shorthand for substances in the solar system. To mix the two would be potentially misleading. Serendipodous 07:32, 18 May 2009 (UTC)

- Except gas, a 'formal state of matter', is already mixed with ice and rock which are not. I don't see why including plasma would be misleading - are people really that likely to conclude that ice or rock is a state of matter because it appears on a list with plasma? Olaf Davis (talk) 14:12, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- The classification into gas/ice/rock is only about chemical composition, and nothing more. The phase of the matter is irrelevant. The plasma can be made of gas/ice/rock too. Ruslik (talk) 13:50, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- My experience is that 'rock' and 'ice' are only ever used to refer to solid matter - indeed, I wouldn't really know what a 'rock plasma' would be. A plasma whose ionic abundances are similar to elemental abundances in rock? I'd be very surprised to come across it used to mean that, but perhaps that's down to my ignorance. Is that what you mean? Olaf Davis (talk) 14:20, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, the plasma with rock abundances will be rock plasma. Meanwhile iron in the Earth core is not solid. Ruslik (talk) 15:51, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- And would a planetary scientist call the iron in the core a 'rock' too? (After this I promise I'll stop indulging my curiosity on the talk page!) Olaf Davis (talk) 16:08, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- See definition of 'rock' in the article. Ruslik (talk) 19:39, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- And would a planetary scientist call the iron in the core a 'rock' too? (After this I promise I'll stop indulging my curiosity on the talk page!) Olaf Davis (talk) 16:08, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, the plasma with rock abundances will be rock plasma. Meanwhile iron in the Earth core is not solid. Ruslik (talk) 15:51, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- My experience is that 'rock' and 'ice' are only ever used to refer to solid matter - indeed, I wouldn't really know what a 'rock plasma' would be. A plasma whose ionic abundances are similar to elemental abundances in rock? I'd be very surprised to come across it used to mean that, but perhaps that's down to my ignorance. Is that what you mean? Olaf Davis (talk) 14:20, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- The classification into gas/ice/rock is only about chemical composition, and nothing more. The phase of the matter is irrelevant. The plasma can be made of gas/ice/rock too. Ruslik (talk) 13:50, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- Except gas, a 'formal state of matter', is already mixed with ice and rock which are not. I don't see why including plasma would be misleading - are people really that likely to conclude that ice or rock is a state of matter because it appears on a list with plasma? Olaf Davis (talk) 14:12, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- Plasma is a formal scientific state of matter, alongside solid, liquid and gas. The terms gas, ice and rock are largely informal shorthand for substances in the solar system. To mix the two would be potentially misleading. Serendipodous 07:32, 18 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, protons and electrons make up the Solar wind. It's in plasma form, though, the "fourth state of matter". So if I'm not mistaken, the plasma of the Solar wind is ionized hydrogen. I'm not sure, though, what the concentration is. Only that it spreads out beyond the planets to form the "heliosphere", a plasma bubble around the Solar system. The paragraph in which the recent edit occurred begins, "Planetary scientists use the terms gas, ice, and rock to describe the various classes of substances found throughout the Solar System." I'm just wondering if this would be improved by making it read ". . . use the terms gas, ice, rock and plasma to describe . . .", and then like the others, just a very brief explanation about plasma? It would need an expert's fine tuning, which unfortunately, I am not. .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 04:15, 18 May 2009 (UTC)

Quote from Earth

What's the "<!--straight quote from first sentence of second paragraph of [[Earth]]-->" note supposed to accomplish? Olaf Davis (talk) 13:07, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- Should we replace the above line by referencing Is there life elsewhere?? -- Kheider (talk) 13:59, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- Sure. Lets. Serendipodous 15:36, 20 May 2009 (UTC)

- It accomplished exactly what it was supposed to - prevent mindless reversion. Why did Serendipodous remove it and leave an edit note of, "Earth: You don't need to justify yourself with that, Harry. It's a bit grandiose, but it's not wrong"? Who needs to make these kind of snide comments? HarryAlffa (talk) 16:31, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Mostly you, it seems. Serendipodous 21:29, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

ṇ== Skip to TOC ==

I added the {{skiptotoctalk}} template for those editors who like to "get right down to it". .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 23:11, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

RfC: Solar System lead is terrible

This Featured Article (!!) lead could be used in the MoS in "How not to write a lead". The emphasis given to material in the lead should roughly reflect its importance to the topic, it should not give one sentence for every single component! HarryAlffa (talk) 17:26, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

I asked YellowMonkey how he passed the lead at a recent FA review, but he didn't reply. HarryAlffa (talk) 17:27, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Actually he did, on his talk page. Serendipodous 17:42, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, I knew you would say that. But "Your first point is very misleading." is not a reply. HarryAlffa (talk) 18:02, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Ah. I didn't realise you'd already got into an argument with him. Serendipodous 18:07, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- You've been to his talk page and seen the extent and nature of it, don't you think the misrepresentation of "argument" is tantamount to out-right lying? HarryAlffa (talk) 20:12, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Actually no. I thought your initial response to him was remarkably uncivil. But then you obviously have a very different definition of civility than anyone here. Serendipodous 11:32, 27 May 2009 (UTC)

- As usual, exaggerated, deliberate, dishonest misrepresentation unworthy of a Wikipeadian, tantamount to out-right lying. See YellowMonkey HarryAlffa (talk) 13:06, 28 May 2009 (UTC)

- You obviously have an issue distinguishing stating a fact from stating an opinion. I was not stating a fact. I was stating my opinion of your behaviour. Take it as you will. Serendipodous 14:26, 28 May 2009 (UTC)

- As usual, exaggerated, deliberate, dishonest misrepresentation unworthy of a Wikipeadian, tantamount to out-right lying. See YellowMonkey HarryAlffa (talk) 13:06, 28 May 2009 (UTC)

- Actually no. I thought your initial response to him was remarkably uncivil. But then you obviously have a very different definition of civility than anyone here. Serendipodous 11:32, 27 May 2009 (UTC)

- You've been to his talk page and seen the extent and nature of it, don't you think the misrepresentation of "argument" is tantamount to out-right lying? HarryAlffa (talk) 20:12, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Ah. I didn't realise you'd already got into an argument with him. Serendipodous 18:07, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, I knew you would say that. But "Your first point is very misleading." is not a reply. HarryAlffa (talk) 18:02, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

Move to close this - it has become disruptive in nature. This is the second (third? fourth?) attempt by the same editor to rewrite the lead per his preferences, despite receiving little or no support for his proposals. --Ckatzchatspy 18:28, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Typical, deceptive misrepresentation. HarryAlffa (talk) 20:02, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

Close this RFC as forum shopping. Ruslik (talk) 19:33, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- You have to laugh at RfC=Forum Shopping :) HarryAlffa (talk) 20:02, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

Ckatz, why be afraid of a wider audience? I said this previous lead was no good, but you swore blind it was fine, over time it became even worse, as soon as I took it for a FA review it was changed, so how right were you? Not very. The article has been controlled by the same 3 or 4 editors for the last year or so (two, three, four?). The FA Review only had one or two additional editors from the usual suspects and they were critical of the lead as it was - hence the (not very good) change. HarryAlffa (talk) 20:02, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

I think it is self-evident that the lead falls down, but would like a MUCH wider audience to assess this, which I hope will result in a better article. HarryAlffa (talk) 20:02, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Harry, no-one here is "afraid" (as you put it) of having fresh eyes look at the article. What is tiresome is your insistence that yours is the only correct viewpoint. You've argued here, through your "summary" articles, and at the FA review pages, only to find that there isn't support for what you want. And yet, you've opened yet another venue with this RfC. You've also been doing much the same thing with regards to the Manual of Style and linking - insisting that you are correct, and others are wrong, despite almost complete opposition. --Ckatzchatspy 20:22, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- I notice the weasel words in there. More personal attacks and misrepresentation, pretty close to out-right lying. HarryAlffa (talk) 21:12, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Mostly you, it seems. --Ckatzchatspy 22:10, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- I notice the weasel words in there. More personal attacks and misrepresentation, pretty close to out-right lying. HarryAlffa (talk) 21:12, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Comment. I support the lead as it is. While it may set forth a few controversial items as truth, such as the only partially settled "Definition of planet" issue and the up and coming "Earth's Moon is actually a major planet" issue, the lead is, after all, the first impression a reader sees. And when talking about a Featured Article such as this, no major changes in the lead or in any other part of the article ought to be made without extrememly close scrutiny, discussion on the Talk page, consensus of all involved editors and formal dispute settlement if necessary. Sorry Harry, you may be correct about the lead needing work; however, since this is a Featured Article, as a serious editor of Wikipedia you are expected to abide by Wikipedia:Defend the status quo. And you will need more support before you're able to justify any major alterations. .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 23:11, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Paine, I am correct, but I nor anyone else serious or not, is bound by any type of essay. The essay Wikipedia:Defend the status quo has nothing to do with the style of the Lead, it is about quality of information, and the lead isn't wrong, it is simply not a summary.

- Comment The lead looks pretty much fine to me as it stands now. It describes in summary fashion what is covered in the article body and gives an overview of the salient features of the solar system. Possibly some of the paragraphs could be shortened a bit to make room for a brief summary of what is in the Galactic context and Formation sections. If that was done, then people could just read the lead and have everything they need to know about the solar system. Franamax (talk) 19:55, 27 May 2009 (UTC)

- Could you further summarize existing paragraphs to make room? HarryAlffa (talk) 13:06, 28 May 2009 (UTC)

- Comment A Request for Comment should be a neutrally-worded polite solicitation of opinions from outside editors, with a view to clarifying or achieving consensus where simple discussion has failed. As such, this is a complete failure, as its wording is likely to polarise respondents and to make reaching consensus more difficult. So for example, while I might be agreeable to making some improvements to the lead paragraph as it now stands, I would strongly disagree with the opinion that the lead is in a "terrible" state. SHEFFIELDSTEELTALK 14:36, 28 May 2009 (UTC)

- Looks fine to me: I came here straight out of the blue, from an RfC list I'd never seen before, via some odd path from my Watchlist. And, while the lead might have been a bit slow, a bit long and slightly pedestrian, and while even the most brilliant leads can usually benefit from periodic re-examination and tweaking, this one was quite interesting and told me, as a layman who has no particularly strong interest in astronomy, just about everything I'd want to know and everything I might want to investigate further, even if I hadn't known or wondered about them before. —— Shakescene (talk) 15:09, 1 June 2009 (UTC)

- But if you didn't read the article, you cannot determine if it conforms to WP:Lead. It doesn't. By your experience of reading it (bit slow, a bit long and slightly pedestrian) also confirms my feeling that it is to poor for a Featured Article - "fine" & "quite interesting" doesn't cut it. HarryAlffa (talk) 14:12, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- If it's fine and quite interesting to readers, then this has to at least partially "cut it". And another concern is what the lead was like at the time Solar System became FA. The lead can't be too shabby if today's lead is pretty much what it was when it achieved FA status. And now look above! This article is also considered a "vital article in science". Seems to me the entire article including the lead is more than acceptable just as it is. .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 14:39, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- But if you didn't read the article, you cannot determine if it conforms to WP:Lead. It doesn't. By your experience of reading it (bit slow, a bit long and slightly pedestrian) also confirms my feeling that it is to poor for a Featured Article - "fine" & "quite interesting" doesn't cut it. HarryAlffa (talk) 14:12, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Comment: Looks fine to me dude.. I thought it was a great introduction to the article, being very informative and interesting. Btw, why is the RfC so biased? Aren't they supposed to be NPOV and civil to get better comments? Stating only one side of the argument (and it seems to be a lonely side?) only helps in polarizing debate, which is never good. Give it a rest, dude.. the lead is fine. --Dudemanfellabra (talk) 05:54, 12 June 2009 (UTC)

Doubled image not resolved

The following was archived before my question was answered:

Layout and images

I've made a few tweaks to image layout - hope no-one minds. Could someone add a footnote to this image? I have absolutely no idea what it shows and the article doesn't seem to mention it either. Thanks Smartse (talk) 13:10, 3 May 2009 (UTC)

- The present caption looks okay, and readers can click on the image for details. There is another similar image just above this one on the left. Are both really needed? If I had to choose which to stay, I would opt for this one. .`^) Painediss`cuss (^`. 21:58, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

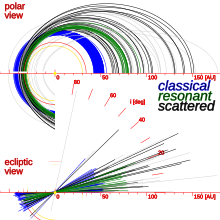

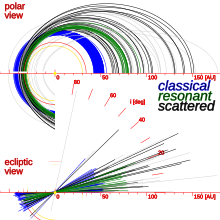

(out) And I ask again, are both these images really needed in the article? One is on the left in the Kuiper belt subsection, and one is on the right in the Scattered disk subsection. Why does this article need both? .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 20:11, 20 June 2009 (UTC)

- Because one shows the Kuiper belt and the other shows the scattered disc. Serendipodous 20:15, 20 June 2009 (UTC)

- I do get that, Serendipodous, I do. My question is still out there because the image above shows both. And since they're so much alike, isn't it possible that the inclusion of both images is confusing to readers? .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 21:08, 20 June 2009 (UTC)

- It would be confusing regardless, because the current state of knowledge is confusing. It isn't easy to separate the Kuiper belt from the Scattered disc, and many astronomers don't. However, the Minor Planet Center, which is the closest thing we have to an authority on the subject, does, so we do. Serendipodous 08:26, 21 June 2009 (UTC)

- I suspect the average reader pretty much skips over those diagrams since the region beyond Neptune is generically all basically the same. Most average readers consider the asteroid belt as a single generic region and don't care about the inner vs outer asteroid belt or the kirkwood gaps. -- Kheider (talk) 15:08, 21 June 2009 (UTC)

- While agreeing that our readers believes the region beyond Neptune is all the same to assume our readers don't care to inform themselves is completely contrary to our spirit of being an encyclopedia that educates people, and is an assumption we should never make. Thanks, SqueakBox talk 16:03, 21 June 2009 (UTC)

- I suspect the average reader pretty much skips over those diagrams since the region beyond Neptune is generically all basically the same. Most average readers consider the asteroid belt as a single generic region and don't care about the inner vs outer asteroid belt or the kirkwood gaps. -- Kheider (talk) 15:08, 21 June 2009 (UTC)

- It would be confusing regardless, because the current state of knowledge is confusing. It isn't easy to separate the Kuiper belt from the Scattered disc, and many astronomers don't. However, the Minor Planet Center, which is the closest thing we have to an authority on the subject, does, so we do. Serendipodous 08:26, 21 June 2009 (UTC)

- I do get that, Serendipodous, I do. My question is still out there because the image above shows both. And since they're so much alike, isn't it possible that the inclusion of both images is confusing to readers? .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 21:08, 20 June 2009 (UTC)

What is our solar system called?

If our galaxy is the Milky Way Galaxy, what is our solar system called? Our planet is "Terra" right? ~~ —Preceding unsigned comment added by 75.15.129.249 (talk) 06:40, 30 May 2009 (UTC)

- Our Solar System is called the "Solar System." Technically the term "other solar systems" is inaccurate, but there isn't an accepted term for extrasolar systems yet. Our planet is called "Earth" or "the Earth." It is called "Terra" in Spanish and Portuguese. For the record, our star is called "the Sun" (capitalised) and our natural satellite is called "the Moon" (capitalised). "Sol" and "Luna" are only used in Spanish, Portuguese and science fiction. Serendipodous 06:46, 30 May 2009 (UTC)

- "Sol", "Luna" and "Terra" are not Spanish: they are Latin names. Spanish, Portuguese, Italian (and maybe some other Neo-Latin language that I'm not aware of) kept this ancient words. Even the English word "Solar" came from the Latin word "Solaris" (of the Sun). Latin was the international language of science for centuries, at least until the 17th century (e.g. Sir Isaac Newton wrote in Latin), but some Latin texts were still written afterward. Of course in english they got different names and in all languages I know the Moon is called (the equivalent of) "Moon". The Moon is the name of a natural satellite, the Sun is a star, the same as Sirius, Rigel, Merak, ... you could call them "suns", but they are stars, and a star can own a planetary system or after the name of the main star: "Epsilon Eridani System" Negadrive (talk) 10:56, 7 July 2009 (UTC)

- The words "terra" and "luna" are no older than the words "Earth" and "moon"; they've just been written down longer. Spanish, Portuguese and Italian retained those words because they are descended from Latin. English is a Germanic language, and so uses Germanic words. And yes, while Latin was the international language of science for many centuries, Latinising a word doesn't necessarily afford it any more scientific credibility. My main issue with this, and I admit I do have a bee in my bonnet about it, is that the determination shown by some people on Wikipedia (not in this discussion, but certainly in other instances) to Latinise the Sun and Moon's names to make them more "scientific" really only makes them look like realistically-challenged geeks who've been reading too many Asimov novels, which does few wonders for Wikipedia's already strained credibility. Serendipodous 12:15, 7 July 2009 (UTC)

- "Sol", "Luna" and "Terra" are not Spanish: they are Latin names. Spanish, Portuguese, Italian (and maybe some other Neo-Latin language that I'm not aware of) kept this ancient words. Even the English word "Solar" came from the Latin word "Solaris" (of the Sun). Latin was the international language of science for centuries, at least until the 17th century (e.g. Sir Isaac Newton wrote in Latin), but some Latin texts were still written afterward. Of course in english they got different names and in all languages I know the Moon is called (the equivalent of) "Moon". The Moon is the name of a natural satellite, the Sun is a star, the same as Sirius, Rigel, Merak, ... you could call them "suns", but they are stars, and a star can own a planetary system or after the name of the main star: "Epsilon Eridani System" Negadrive (talk) 10:56, 7 July 2009 (UTC)

COOL

I WANT TO DO A PROJECT ON THE SOLAR SYSTEM, BUT I THINK IT'LL BE HARD! SO I NEED TO GO TO THE DOLLARE STORE AND GET SOME CLAY! MAYBE SOME COLOURFUL CLAY! THAT'LL WORK!!!! —Preceding unsigned comment added by 174.113.44.61 (talk) 19:25, 20 June 2009 (UTC)

- How's that coming along? Serendipodous 12:15, 7 July 2009 (UTC)

Extrasolar systems

I'm looking, but I can't see a single term for the generic version of our Solar System. You know, a star and its associated bodies beyond ours. Am I missing something? Otherwise this seems like quite a massive oversight in the terminology. Surely people who study this kind of thing must have a term for it? Star system generally encompasses this in sci-fi, but it seems the technical term only applies to stars in close association. --62.31.151.92 (talk) 21:19, 11 July 2009 (UTC)

- My guess is that, since we've never actually been to any other extrasolar locations, there isn't a distinct term for "Extrasolar system" except perhaps that phrase itself. Solar System is supposedly specific to our own system, but... I don't know, saying that using the term with an "Extrasolar system" is incorrect seems hyper-technical/pedantic to me. Is there a real need for a distinct phrase?

— V = I * R (talk) 21:42, 11 July 2009 (UTC)

Maya Solar system

I've read that the earliest known evidence for studies of the Solar system (and astronomy in general) by the Maya dates back to 300 BCE. So while their accomplishments are many and impressive, like usage of zero in their astronomical calculations, they are not really notable as an exception to the "many thousands of years" claim. It would be interesting to see some of these "notable exceptions". If examples are not given, isn't this an example of weasel words?

— .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 07:30, 2 August 2009 (UTC)

- The Maya did not believe in a heliocentric cosmos, as far as I'm aware. Notable exceptions are mentioned in the main Discovery and exploration article. Serendipodous 14:46, 2 August 2009 (UTC)

Where are the moons?

Very good article!

One very important thing is missing, in my opinion. It baffles me how in a discussion on the Solar System, or Planets, or the like, this part seems always left out. One could believe that the entire astronomical community was purposely discriminating by leaving out this very important group of solar system bodies!

What I am talking about are the moons. Just because they travel in secondary orbits, why does it seem that they are not worthy of mention? Certainly they are members of the Solar System, too.

The moons fall into three sizes, if classified by mass:

1. The large moons, specifically, Earth's Moon (Luna), Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, Titan, and perhaps Triton, are basically planets that rival the likes of Mercury and the terrestrial planets. Certainly they deserve mention individually or collectively as a group. These large bodies are more substantial than any of the dwarf planets like Ceres or the Kuiper Belt dwarfs that are mentioned in the article.

2. The medium-sized, or dwarf-planet sized moons. Four to seven of Saturn's moons and four or five of Uranus' compare well with Ceres in size. Triton is about the size of Pluto. (I believe the IAU should be considering a "dwarf moon" definition.)

3. The very small moons are more or less like the astroids and comets that orbit the sun. Even so, Phoebos, Deimos, and several others in this category have names and are well known.

Another nice way to classify these bodies would be geologically: "rocky" moons (Luna) vs. "icy" moons. Titan even has a subtantial atmosphere making it more like Earth, Venus, and Mars, than like Mercury, any other moon, or dwarf planet. GeoPopID (talk) 20:36, 22 August 2009 (UTC)

- The moons are mentioned, briefly, in their respective planet sections. I agree that the moons are worth a lot more then that, but I can't see giving each of the 19 round moons its own section; that would overwhelm the article, I think. Serendipodous 03:43, 23 August 2009 (UTC)

- The moons are mentioned at the bottom of the structure section. I agree that the spherical moons are important, but I am not sure we want to get too wordy in a general article about the solar system. Of course suggestions are always welcome. -- Kheider (talk) 16:52, 23 August 2009 (UTC)

Editor Assistannce

Hi Ckatz,

You removed a quotation placed in the notes section with the reason give "excessive quote, should be integrated in a different manner." Being new to Wiki, I couldn't find any information on what constitutes an excessive quotation, nor any definition of how to "integrate" this quotation.

Stephen G. Brush's quotation is relevant to the claim being made, and improves the Wiki article I think. He is certainly an expert in the field. Could you help me out with some Editor assistance and point me to some information on what constitutes an excessive quotation and how best to integrate this information into the article, assuming those are the only two reasons you removed the quotation.

I was unsure if I could use my own words to shorten Brush's essential point, so I quoted just enough to make clear his point. Perhaps a parapharase with less quoted material, if that would be better. Any suggestions and help are welcome.

If anyone else can suggest a good way to integrate the following, it would be greatly appreciated:

Scientist and historian Stephen G. Brush published in his Fruitful Encounters: The Origin of the Solar System and of the Moon from Chamberlin to Apollo (Cambridge series: A History of Modern Planetary Physics volume thee; Cambridge University Press; 1996.):

The origin of the Solar System is one of the oldest unsolved problems in science. It was first perceived as a scientific question distinct from the origin of the universe as a whole, in the 17th century. The introduction by Copernicus of the heliocentric theory made it meaningful to use the modern phrase “Solar System.” Astronomers began to think of the Sun as one of many stars; it became conceivable that our Solar System was one of many such systems, and that it had been affected or even created by celestial bodies from other systems. René Descartes, in the 1630s, developed a qualitative hypothesis for the development of the Solar System within a larger system, using his theory of vortexes. Thus the most fundamental question one could ask about the origin of the Solar System is: Did it develop autonomously along with the Sun itself, or did it come into existence because of the action of outside entities? (Brush 1996: 3)

Twentieth-century astronomers have argued that these two alternatives, known as the “monistic” and “dualistic” kinds of theories, lead to radically different conclusions about the probability of finding life elsewhere in the universe. If the development of our Solar System was monistic, then we may infer that planet formation is a natural consequence of star formation, and hence there are many habitable planets. But if a dualistic process like the close encounter of two stars is needed to explain the origin of the Solar System, then because of the great distance between stars, planet formation will be a rare event and the chance of life extremely small.

Sometimes people want to know the presently accepted “right answer” to a question before studying its history. Is the monistic or dualistic theory really correct? The last time I consulted the experts, they were quite convinced that the origin of the Solar System was monistic, although they disagreed about some important aspects of planetary development. But the history of planetogony during the last two centuries doesn’t give much reason for confidence that this conclusion is final. Throughout the 19th century scientists accepted the monistic Nebular Hypothesis; then they switched to a dualistic theory (close encounter of another star with the Sun). But this theory was rejected after 1935, and a monistic theory (collapse of a gasdust cloud) was revived in the 1940s. Between 1976 and 1984 the dualistic “supernova trigger” theory was accepted, then rejected. It was revived in 1995. The time scale for reversing the answer gets shorter and shorter as one approaches the present, giving us very little reason to think that today’s answer will still be considered correct tomorrow. That’s why I said that the problem is unsolved.

For the historian of science, this uncertainty about the correct answer does have one important advantage. It undermines the tendency to judge past theories as being right or wrong by modern standards. This tendency is the so-called “Whig interpretation of the history of science” that one usually finds in science textbooks and popular articles. The Whig approach is to start from the present theory, assuming it to be correct, and ask how we got there. For many scientists this is the only reason for studying history at all; Laplace remarked, “When we have at length ascertained the true cause of any phenomenon, it is an object of curiosity to look back, and see how near the hypothesis that have been framed to explain it approach towards the truth” (1966: vol. 4, 1015).

But Whiggish history is not very satisfactory if it has to be rewritten every time the “correct answer” changes. Instead, we need to look at the cosmogonies or planetogonies of earlier centuries in terms of the theories and evidence available at the time.

I think another well known scientist expressed the importance of historical perspective well when he writes:

R. A. Fisher said it well:

More attention to the history of Science is needed, as much by scientists as by historians, and especially by biologists, and this means a deliberate attempt to understand the thoughts of the great masters of the past, to see in what circumstances or intellectual milieu their ideas were formed, where they took the wrong turning or stopped short on the right track." (R. A. Fisher, 1959, cited in Wilkins, Adam S. The Evolution of Developmental Pathways. Massachusetts: Sinaur Associates; 2002; p. 3.)

The current theory is just that, and we do well to allow room for distenting views, no matter how minor they are, for it reminds us of the tentative nature some hypotheses, to wit Woolfson's comments on plantetary formation:

While having material at the right distance from the Sun is a necessary condition for a plausible theory, that by itself is not sufficient. It must also be shown that the material forms planets.

None of the monistic theories we have considered so far has even considered this problem in any detail. Laplace suggested that clumps in his rings would form by gravitational attraction and that then the clumps would combine. Actually, it is possible to show that unless his rings had masses very much greater than that of planets, the rings would have been very unstable and would have dispersed to give a disk without rings in very short time -- much shorter than the time required for clumping to take place. The end result would be a fairly structureless disk within which the planets must form -- a similar situation to that obtained with the cloud capture model. (Woolfson 2007: 88)

The floccule theory produces planets by concentrating cloud material through collisions. It is certainly true that colliding material would be compressed but it simply would not produce planetary masses in a large cloud. The turbulent streams in such a cloud would have had masses similar to the Jeans critical mass for cloud material and these would have been of stellar mass. When they collided, stellar-mass condensations would have been produced. (Woolfson 2007: 88-89)

The only theory that hints at how planets could be successfully formed is that of Jeans. The break up of filament into a set of blobs under gravitational effects is well founded theoretically and, as will be shown in Chapter 28, has also been successfully modelled. The problem with Jeans theory was not that that mechanism for producing planets was unsatisfactory but rather that it was being applied to the wrong material. It is quite possible to have material in a filament at a density and temperature that would give planetary mass blobs with greater than the Jeans critical mass. This certainly requires that the material should be at a temperature much lower than that of typical solar material -- but that requirement is also indicated by the quantities of the light elements lithium, beryllium and boron in the Earth's crust. (Woolfson, M. M. The Formation of the Solar System [Theories Old and New]. London: Imperial College Press; 2007; pp. 88-89.)

This article states, "The Solar System formed from the gravitational collapse of a giant molecular cloud 4.6 billion years ago." Yet, this is really one current hypothesis among others. It addresses some questions better than others; and others addresses some questions better than it, as Brush and Woolfson make clear. Statements like this on Wiki, with no allowance for such historical views as Brush or Woolfson, are indeed "whiggish." One would hope Wikipedia can do better than this, otherwise it will end up being little more than a "bandwagon" parroting the latest "correct" theory with a certain ahistorical blindness.

The history of science is peppered with ideas that have held sway, that were eventually found to be flawed and were then replaced by some new ideas. The lesson to be learnt from this is that no theory can every be regarded as 'true'. There are two categories of a theory -- those that are plausible and those that are implausible and therefore probably wrong. Any theory in the first category is a candidate for the second whenever new observations or theoretical analysis throw doubt upon its conclusions. There is no shame in developing a theory that is eventually refuted. Rather the generation and testing of new ideas must be regarded as an essential part of the process through which scientists gain knowledge and understanding they seek.... A seeker after knowledge and understanding must be cautious about accepting ideas because they seem 'obvious' and fit in with everyday experience.... The watchard in science is "caution". All claims must be examined critically in the light of current knowlege. Any acceptance must be that of the plausibility of an idea since the possibility of new knowlege and understanding to refute it must be kept in mind. We must be aware of bandwagons and be prepared to use our own judgements; history tells us that bandwagons do not necessarily travel in the right direction! (Woolfson, M. M. The Formation of the Solar System [Theories Old and New]. London: Imperial College Press; 2007; pp. 88-89.)

So my realy concern and question is, what is the proper way to integrate the historical perspective into Wikipedia's articles? Any and all help and suggestings welcomed. Thanks

Dogyo (talk) 00:55, 23 August 2009 (UTC)

- You might be interested in reading the article History of Solar System formation and evolution hypotheses. As a rule, when discussing broad topics like the Solar System, Wikipedians are loath to bring in competing or older ideas about the topic, and prefer to reflect the current consensus, leaving any ambiguities for sub-articles. Serendipodous 03:48, 23 August 2009 (UTC)

I believe you missed the meaning of Brush and Woolfson. Woolfson is clearly pointing out there are competing ideas (hardly old, unless you consider 2007 old ;-) And Brush is making an historical point that gives historical context to Woolfson. This kind of ahistorical selection of the most popular theory as being "fact" while ignoring there are other hypothesis that are being currently published by reputable scientist because they are considered "old" or not "fact" sounds like a textbook definition of "whiggish" ;-) It seems if Wikipedia seeks to be actually factual it would be better to say something along the lines that "current consensus says X," and then cite the other contrary views and reference them. Otherwise it is actually not factual when there actually exists multiple working hypotheses, any one of which is currently held to be the "consensus view," but nevertheless there exists plausible alternative hypotheses.

Chamberlin's most enduring single publication was probably his Science article, "The Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses," published in 1890, reprinted in many journals, and available as late as 1977 from the American Association for the Advancement of Science as a reprint. This article is a strong attack on the tyranny of dominant hypotheses. As his initial summary says, "With this method the dangers of parental affection for a favorite theory can be circumvented." Even today, one finishes reading this article with a determination to rethink one's own research to see what damage theory-induced bias has inflicted. Not better statement of the matter can be found than this passage from the second section of his article:

The moment one has offered an original explanation for a phenomenon which seems satisfactory, that moment affection for his intellectual child springs into existence; and as the explanation grows into a definite theory, his parental affections cluster about his intellectual offspring, and it grows more and more dear to him, so that, while he holds it seemingly tenative, it is still lovingly tenative, and not impartially tenative. So soon as this parental affection take possession of the mind, there is a rapid passage to the adoption of the theory .... Instinctively there is a special searching-out of phenomena that support it, for the mind is led by its desires. [Thomas C. Chamberlin, "The Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses," Science, 1890, 15:92-96.] (Newman, Robert P. American Intransigence: The Rejection of Continental Drift in the Great Debates of the 1920s. Earth Sciences History. 1995; 14(1):62-83.)

What is the policy or goal of Wikipedia when there is more than one working hypothesis even if one or the other is more popular at any given time? It is one thing to bring up an "old" hypothesis when their is no plausible or verifiable citation from scientists supporting it (Brush calls that "priggish"), but one would think, according to the verifiability principle if there are scientists raissing questions or weighing the relative pros and cons of two different hypotheses, even if one was once considered "old," but is not being reconsidered. There are a number examples just such cases within various fields of the scientific community today, and there are numerous reputable, verifiable, citations in the literature addressing just such cases.

But back to my original question. Wikipedia articles most certainly present themselves as being factually and historically accurate, which would include issues like I am raising. And the article you linked to above seems to be historically oriented (and perhaps may be a better palce for this kind of material (I am seeking guidance on this issue here), but how then does this kind of historical material relate to the other entries on the same topic? It would indeed be an odd situation if one article makes a claim that is inconsistent with a fuller and more factually (i.e., historically) nuanced picture in other article. What would this say about Wikipedia as an accurate source of so-called "factual" knowledge?

I would also point out the reason given for the original edit had nothing to do with "older ideas" or "current consensus," but with a "excessive quotation" and the need for better "integration." It would be nice to have a bit more specific information on each one of these, perhaps some examples even.

So I am a bit unsure how to proceed. Would this material then be placed into a sub-article? Why not a footnote in a relevant existing article? How does the sub-article relate to other articles on the same topic?

Grateful for your suggestions and hopefully I will slowly get the hang of this Wiki thing ;-) A bit daunting and confusing at first to be honest.

Dogyo (talk) 05:23, 23 August 2009 (UTC)

Regardless, any discussion on that issue is best kept to the appropriate sub article. Otherwise this article, which is mainly focused on the geography of the Solar System, will be overwhelmed. Serendipodous 06:35, 23 August 2009 (UTC)

So, just to be sure, is it your view the appropriate sub-article is History of Solar System formation and evolution hypotheses? Thanks for the pointer.

Dogyo (talk) 06:59, 23 August 2009 (UTC)

- Yes. That is the article for which this information is best suited.Serendipodous 08:31, 23 August 2009 (UTC)

Request quotation for Rock, Ice & Gas using 'melting points'

Planetary Science Research Discoveries define both Volatile & Refractory in terms of vaporizing (boiling) temperatures. The reference supplied to justify the current article text is not freely available. Could someone please supply a quote from Further investigations of random models of Uranus and Neptune which justifies using "melting point' instead of 'boiling point' in a general definition. HarryAlffa (talk) 15:43, 28 August 2009 (UTC)

Request quotation for Interplanetary medium

"Earth's magnetic field stops its atmosphere from being stripped away by the solar wind. Venus and Mars do not have magnetic fields, and as a result, the solar wind causes their atmospheres to gradually bleed away into space."

This part of the article uses "Erosion by the Solar Wind[1]" as a reference. It is not freely available, could someone give an apropriate quote please? HarryAlffa (talk) 17:03, 28 August 2009 (UTC)

Request quotation for Sun

Nuclear fusion details seem incomplete. HarryAlffa (talk) 16:50, 28 August 2009 (UTC)

- Incomplete how? This isn't the article to go into the fine details of hydrogen/helium/carbon fusion cycles. Serendipodous 07:34, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- This phrase, "gives it an interior density high enough to sustain nuclear fusion", is incomplete to the point of misleading, and has no source. HarryAlffa (talk) 16:31, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

Who says it is moderately large? HarryAlffa (talk) 16:50, 28 August 2009 (UTC)

- The Sun is often described as an "average star". If a source means that much to you, I can get one. Serendipodous 07:34, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- Never mind. Not worth it. Serendipodous 07:43, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

Red dwarfs make up 85 percent of the stars in the galaxy. Is this definite, and recent? HarryAlffa (talk) 16:50, 28 August 2009 (UTC)

- It's there in the source. "Scientists estimate that red dwarfs make up to 85 percent of the stars in our Galaxy." Ker Than, 2006.Serendipodous 07:34, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- So it's not definite. HarryAlffa (talk) 18:40, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- Of course not. Nothing in science ever is. Serendipodous 05:31, 31 August 2009 (UTC)

- So it's not definite. HarryAlffa (talk) 18:40, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

Request quotation for Mars

There are obvious claims here in error. HarryAlffa (talk) 16:52, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- As I said when I reverted your comment, "substantial" is a relative term. Mars's atmosphere is indeed substantial when compared to those of Mercury and Europa. Serendipodous 16:56, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- It's a tenuous use of language. But there are errors - plural. HarryAlffa (talk) 17:45, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- You have yet to explain what they are. Serendipodous 05:12, 31 August 2009 (UTC)

- It's a tenuous use of language. But there are errors - plural. HarryAlffa (talk) 17:45, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

Request quotation for Galactic context

The source is a Powerpoint Presentation in Italian. HarryAlffa (talk) 17:43, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- Hiya, Harry. I can't speak nor read Italian, so here are two supportive sources for that Italian paper. I'm not experienced enough to be certain they qualify as reliable sources; however, they both back up the claims:

- I also learned that, while the bright star Vega is the approx. solar apex, the bright star Sirius is the approx. solar antipex (the direction opposite of the solar apex and the direction we are traveling from).

- — .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 09:04, 30 August 2009 (UTC)

Request quotation for Terminology section

New Horizons Set to Launch on 9-Year Voyage to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, supports the third sentence of the Terminology section; where? HarryAlffa (talk) 19:14, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- "Pluto suddenly became the star representative of an unexplored region of the solar system, sometimes referred to as the "third zone.""Serendipodous 05:08, 31 August 2009 (UTC)

Request quotation for Venus section

Two sources for Venus, give me two quotes please. HarryAlffa (talk) 19:35, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- Both those sources are freely accessible. Serendipodous 05:13, 31 August 2009 (UTC)

Request quotation for Kuiper belt section

- Many Kuiper belt objects have multiple satellites?

- and most have orbits that take them outside the plane of the ecliptic?

HarryAlffa (talk) 20:24, 29 August 2009 (UTC)

- Why do you need quotes? These aren't controversial facts. And they're sourced. So what's the big deal? Serendipodous 05:32, 31 August 2009 (UTC)

{{editsemiprotected}}

Please change the caption. This is not a map, and it's filled with spelling mistakes.

- A reference map or our location in the universe. Click to veiw more detail.

change to

- A diagram of our location in the Local Supercluster. Click to view more detail.

The claim about the universe goes to far, the diagram only extends to the Virgo Supercluster.

76.66.196.139 (talk) 00:23, 21 September 2009 (UTC)

Done by Kheider (talk), with additional edits by...

Done by Kheider (talk), with additional edits by...- — .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 09:04, 21 September 2009 (UTC)

Images

This article is getting a bit image-crowded. I just reverted a newbie's image on the grounds that it caused two images on both sides of the text to face each other, which violated MOS, then realised that half the images in the article did that as well. I think it might be a good idea to do an image check to see which ones are truly necessary and which ones are unneeded. I'm too close to this to make an impartial judgement, so others' input would be appreciated. Serendipodous 17:54, 27 September 2009 (UTC)

- I agree entirely, the article seems structurally like it could be improved upon, but the images are a major threat to the article losing it's FA status.--Ben Harkness (talk) 01:03, 28 October 2009 (UTC)

Image list:--Ben Harkness (talk) 02:22, 28 October 2009 (UTC)

1

Change. Great quality image (size, detail, accuracy). Would, however, like to links to planets from this image as some anatomy articles have.

2

Delete. Effective diagram, not easily read. Realization of size could be better understood in main image.

3

Change/Delete. Information is important but could be explained in text. If a visual is necessary, a more exact graph (line graph) could be used.

4

Delete. Orbits should be shown but this image seems ineffective. Image is too large, should be formatted as a thumbnail. Perhaps and animated .gif showing general orbits would work better.

5

Delete. Regions could be shown in main image, orbits can be shown more effectively in above image suggestion.

6

Delete. Main image for Sun. Purely artistic in the article, non informative.

7

Keep. Educational and important, wish a better image existed to better diagram the medium.

8

Delete. Again, purely artistic in the article; also a very old image, better aurora images could be found.

9

Keep... for now. excellent image, would like a page wide image showing correct scale (if that's possible, I could be very wrong).

10

Keep. Asteroid belt image is important. Does a better diagram exist? Also, not formatted as a thumbnail, therefor over sized.

11

Delete. Too close to asteroid belt image when the sections are so short. Link to Ceres gives the exact same image.

12

Change. Should be formatted the same as the inner planets image.

13

Keep. Again, purely artistic, but proves useful and keeps the article from feeling empty.

14

Delete. Not at all effective. Not formatted properly, and too difficult to read.

15

Delete. I have a feeling very few readers will have any idea what is happening in this image.

16

Change. Perhaps an image like the inner plantes and gas giants, formatted the same way, could work.

17

Delete. Another confusing image that nobody will find useful.

18

Delete. Should be included in the suggested Pluto diagram.

19

Delete. Not important to the article.

20

Change. Important diagram, poorly executed.

21

Delete. Not convinced the image is important to the article.

22

Change. Location of our system in the galaxy is important to understand but a diagram isn't very visually pleasing. I suggest a picture of our galaxy (an artist's rendering I think would work well) with our location pointed out in that image.

23

Delete. Unimportant.

24

Change. Both images 22 and 24 could be merged to show the same information. An image formatted to the same size as this image currently is could be cool.

25

Delete/Change. An image showing the same information could be useful but this particular image is completely ineffective.

26

Change. Not a very good red giant image. This image could be much more effective.

I've dealt with most of the issues you raised. I kept 4 and 22 because as of right now I can't think of an alternative. I swapped out 6 because I felt that a Solar System article without a picture of the Sun was a bit odd. I think the new image is more informative. 14 may not be the prettiest image on the planet, but it is the most accurate image of the Kuiper belt available free anywhere. I have to disagree with you on 19, I think it illustrates what would otherwise be a difficult to understand concept. As for 20, would this one be better? It was the original but got swapped out. I don't really have the image experience to rework these pictures myself. Someone else will have to do it. Serendipodous 08:30, 28 October 2009 (UTC)

Number of satellites of Outer planets - words or digits?

Since this article is fairly technical and has lots of numbers, it might be easier to have the large numbers of satellites of the outer planets in digits rather than words. It might even save a line or two. E.g. "Jupiter has 63 known satellites." instead of "Jupiter has sixty-three known satellites." It might also make translations and reading by non-"English as a first language" persons easier. Facts707 (talk) 04:44, 9 November 2009 (UTC)

- Good idea :) Serendipodous 09:12, 9 November 2009 (UTC)

Remove template

Suggest removing the "Systems and systems science" template ... random list of unconnected topics that just happen to contain the word "system". —Preceding unsigned comment added by 86.152.242.150 (talk) 14:37, 11 November 2009 (UTC)

what two scientist believed the sun was the center of the solar system —Preceding unsigned comment added by 71.176.43.127 (talk) 22:33, 6 January 2010 (UTC)

Heliopause

Please don't take this wrong, Serendipodous, for I consider your clarification to be an excellent edit. I'm curious about what you wrote in the edit summary: ". . . the solar wind has no upwind or downwind." In that particular context, where the "upwind" and "downwind" refers to the flow of the interstellar medium, the motion of the Solar wind is, of course, always into that medium. In other contexts, such as the effect of the Solar wind upon the magnetic field of the Earth, there is a significant "upwind" and "downwind" to the Solar wind, isn't there? (Ref.: Earth's magnetic field)

Also, a later statement is made that "Beyond the heliopause, at around 230 AU, lies the bow shock, a plasma 'wake' left by the Sun as it travels through the Milky Way." This raises questions in my mind: How can science assume that there is a "flow" to the interstellar medium, when next to nothing is known about that medium? Might that medium be immobile, and only appear to flow against the movement of the Sun and Solar system around the center of the galaxy? Isn't it incorrect to refer to the "flow" of the interstellar medium in this article as if it definitely exists? The only thing actually "flowing" could just be the Solar system through the galaxy, correct? (If I'm right about this, then there is no "upwind" or "downwind" to the interstellar medium!) It seems we are using terms (such as "flow of plasma", "upwind" and "downwind") in this article as if they truthfully apply, when, in truth, we don't know if they apply, don't you agree?

— .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 05:51, 4 September 2009 (UTC)

- I suppose there is an upwind or downwind to the solar wind; towards or away from the Sun. But since both edges of the heliopause are away from the Sun, the solar wind's upwind and downwind wouldn't apply. As to the interstellar medium being immobile, that's impossible. Nothing in space is immobile, because nothing can be. Space has no gravity and no friction, so there's nothing to slow anything down. Serendipodous 06:06, 4 September 2009 (UTC)

- You can read here or here. Ruslik_Zero 08:01, 4 September 2009 (UTC)

- That's all quite interesting, but it's still conjecture and OR. There's nothing in the literature that I know of that would support your idea that it's "impossible" for the interstellar medium to be immobile. Moreover, if the interstellar medium is flowing, who's to say it's not flowing in the same direction as the Solar system? or in a "crosswind" direction? Bottom line is nobody really knows for certain, so the "flow", "upwind" and "downwind" wording must be OR, and it ought to be removed from this encyclopedia.

- — .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 08:27, 4 September 2009 (UTC)

- Ruslik just provided you with two scientific sources that describe the heliopause's interaction with the motions of the interstellar wind. Serendipodous 09:28, 4 September 2009 (UTC)

- "This current of tenuous partially ionized low density ISM has a velocity relative to the Sun of ∼26 km s−1." This is written on the page one of one of two refs that I provided. Ruslik_Zero 10:08, 4 September 2009 (UTC)

- Another paper: "At present there is no doubt that the local interstellar medium (LISM) is mainly partially ionized hydrogen gas moving with a supersonic flow relative to the solar system." Ruslik_Zero 10:13, 4 September 2009 (UTC)

- And doncha jus' luv it! when a "scientist" says "At present there is no doubt . . .". Makes me wanna jump on the next rocket goin' that way just to see if it's really correct. So for now, I shall bow to the present interpretation of data and "back off". And may we all live long enough to see if ol' Vlad is correct.

- — .`^) Paine Ellsworthdiss`cuss (^`. 10:00, 5 September 2009 (UTC)

- We do have spacecraft in that region now. Rocket-launched and everything. The Voyagers have been inside the heliosheath for years and both have noticed it billow and buckle under pressure from the interstellar wind. Serendipodous 15:50, 5 September 2009 (UTC)

New Article http://www.universetoday.com/2009/11/20/cassiniibex-data-changes-view-of-heliosphere-shape/ --Craigboy (talk) 04:42, 19 December 2009 (UTC)

- Bugger. Assuming this is correct I'm going to have to rewrite about 20 different articles. Serendipodous 15:15, 19 December 2009 (UTC)

--Suggested change for "Farthest Regions"--

For the 3rd sentence in the "Farthest regions" section, I recommend we change the word influence to dominance. "However, the Sun's Roche sphere, the effective range of its gravitational dominance, is believed to extend up to a thousand times farther."

While we believe gravitational influence to be practically infinite, using the word "dominance" instead illustrates a better understanding of the concept of the "Roche sphere" or Hill sphere. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Xjxj324 (talk • contribs) 23:57, 26 January 2010 (UTC)

- Good idea Serendipodous 00:05, 27 January 2010 (UTC)

Possible Link

{{editsemiprotected}}

Request: Please add http://www.quitethehike.co.uk to the 'external links section'.

The webpage http://www.quitethehike.co.uk is an interactive look at the size of the galaxy, drawing attention the the distances between the planets themselves. It has some interesting trivia about the planetary objects themselves (which mostly comes from Wikipedia, it seems).

Not done This addition of this link would likely be contested; please obtain consensus here through discussion for its addition. If you are having trouble getting input, ask for a third opinion. CIreland (talk) 11:05, 23 January 2010 (UTC)

Not done This addition of this link would likely be contested; please obtain consensus here through discussion for its addition. If you are having trouble getting input, ask for a third opinion. CIreland (talk) 11:05, 23 January 2010 (UTC)

Ceres, beyond Neptune ?!?

"Beyond Neptune's orbit lie trans-Neptunian objects composed mostly of ices such as water, ammonia and methane. Within these regions, five individual objects, Ceres, Pluto, Haumea, Makemake and Eris, are recognized to be large enough to have been rounded by their own gravity, and are thus termed dwarf planets. "

Ceres is recognized as a dwarf planet. But, Ceres is not beyond Neptune's orbit at all. This wording is misleading. It should be corrected. Cazaux (talk) 22:53, 29 January 2010 (UTC)

- I thought your comment was good until I noticed the lead in. The paragraph starts with: "The Solar System is also home to two regions populated by smaller objects. The asteroid belt, which lies between Mars and Jupiter, is similar to the terrestrial planets as it is composed mainly of rock and metal." -- Kheider (talk) 23:50, 29 January 2010 (UTC)

What's inclination between ecliptic and the galactic plane?

--MathFacts (talk) 10:03, 11 February 2010 (UTC)

- 86.5 degrees. I'll add it.Serendipodous 12:02, 11 February 2010 (UTC)

Planet introduction and overview

Can I suggest that a general introduction to the planets is provided. Or is there a reason why this has not been done already? This could go just before the planets are listed - or in the Formation and evolution section - or the Formation and evolution section, together with a general introduction, could go just before where the planets are listed. I suggest that this could include an explanation of how (and why):

- 1. The temperature of planets drops with distance from the Sun (obvious!)

- 2. The chemical composition of planets varies with distance from the Sun (less obvious)

- 3. Orbital period increases with distance from the Sun.

- 4. Spacing of orbits increases with distance from the Sun.

- 5. Mass of planets increases then tails off with distance from the Sun.

As all these properties are a consequence of the mode of Formation and evolution of the solar system then that explanation could be integrated into such a section. Or should such details only go in the separate Planet article? Any comments? --Tediouspedant (talk) 23:48, 2 March 2010 (UTC)

- The definition of planet is discussed in the terminology section. Points 3 and 4 are discussed in the Structure section. The relative masses of the planets are discussed in the inner and outer planets section. Point 1 might be worth mentioning, and I've been pondering whether and how to introduce the composition gradient (which is tied to temperature) into the structure section. Serendipodous 08:32, 3 March 2010 (UTC)

When was the planet naming convention adopted?

In the article there is no mention about when the current Roman names were assigned to the planets, and this info is not included even in each individual planet article.

For example, Saturn was named after a Roman god, but did the Romans assign the god name to the planet in their time as well? Did Galileo call it "Saturn"? Since when was the planet naming convention adopted?

Thanks John Hyams (talk) 02:06, 12 March 2010 (UTC)

- It was adopted by the Romans. It spread through Europe with the Roman Empire. Since all academic correspondence in Europe til the end of the Renassance was in Latin, there was no need to change the names. See: Planet#Mythology. Serendipodous 05:50, 12 March 2010 (UTC)

- It's not a convention. Mongolians and Tibetan don't use the Roman names for planets. The Sanskrit names are different too. Gantuya eng (talk) 08:05, 12 March 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks Serendipodous. To make it clearer in the Planet article, I have changed the heading name to: Planet#Mythology_and_planet_naming (easier to find the information this way) John Hyams (talk) 13:24, 12 March 2010 (UTC)

Edit request from 87.79.173.91, 11 May 2010

{{editsemiprotected}} Please remove the link [[Universe#Evolution|universe's evolution]] and replace it with simply "Universe's evolution". As seen above, it doesn't work, and not everything needs its own link.

87.79.173.91 (talk) 20:21, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- subbed link Serendipodous 20:34, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

Dark Matter as an Ocean and everything is inside it.

Greetings, health, peace of mind, happiness and the wisdom of the ages to one and all. I am fascinated by all these magnificent discoveries of the Solar System and it's origin. I have been wondering a while about Dark Matter. In my minds eye see how Dark matter could possibly be mass of microcosmic particles, infinitely small, that holds matter and all the elements that make up the stars and planets from quickly falling apart. Samuel Cruz staino@aol.com —Preceding unsigned comment added by 97.100.18.40 (talk) 23:57, 22 May 2010 (UTC)

- Dark matter could be anything at the moment. Until we find some evidence it might as well be cosmic teapots. Whatever it is, it doesn't seem to register below galactic level. Serendipodous 14:20, 23 May 2010 (UTC)

"Heimdall"?

Surfing through the various language versions of "Solar System" and their discussions, I've found out that there is a certain uncertainty whether "Solar system" means anyone of them or just ours. My question: Has there been a discussion on this theme yet; and if not, would the term "Heimdall" for our "home world" be acceptable? Hellsepp 18:16, 1 May 2010 (UTC)

- Heimdall is a crater on Callisto and Mars. Ruslik_Zero 18:18, 1 May 2010 (UTC)

Well, only our solar system contains the parent star Sol as the primary body. Thus only our solar system is a solar system.

Anything else is a planetary system.Carultch (talk) 09:57, 28 May 2010 (UTC)

Artist's rendering of the Oort Cloud, the Hills Cloud, and the Kuiper belt (inset)

Is this an oblique angle view or do they actually revolve in ovals? I think the distinction deserves mention. Richard LaBorde (talk) 23:04, 24 May 2010 (UTC)

Artist's rendering of solar system

What about that rendering? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 94.179.206.243 (talk) 16:26, 12 June 2010 (UTC)

Pending changes

This article is one of a small number (about 100) selected for the first week of the trial of the Wikipedia:Pending Changes system on the English language Wikipedia. All the articles listed at Wikipedia:Pending changes/Queue are being considered for level 1 pending changes protection.

The following request appears on that page:

| Many of the articles were selected semi-automatically from a list of indefinitely semi-protected articles. Please confirm that the protection level appears to be still warranted, and consider unprotecting instead, before applying pending changes protection to the article. |

However with only a few hours to go, comments have only been made on two of the pages.

Please update the Queue page as appropriate.

Note that I am not involved in this project any more than any other editor, just posting these notes since it is quite a big change, potentially.

Regards, Rich Farmbrough, 20:31, 15 June 2010 (UTC).

Inclination angle of the ecliptic

This page currently lists the ecliptic as being angled 86.5° out of the galactic plane. However, this is based on the source Swinburne Astronomy Online, which makes the rather shaky logical leap that the axial tilt of the ecliptic to the celestial equator must add fully with the tilt of the celestial equator to the galactic plane. This would only be the case if the axis of the Earth were precisely coplanar with a vertical radial plane of the galaxy, and moreover, if the center of the galaxy was to be found at approximately 18h and 86.5° inclination.

This statement of the tilt disagrees with the figure given in the Milky Way article of ~60° (second paragraph, 'Appearance from Earth' section). In addition, the Galactic Center article lists the position of the center of the galaxy as being at RA 17h45m40.04s, Dec -29° 00' 28.1". I've been unable to find independent verification of either of those values, and neither is cited, but both are consistent with one another, as shown in this rough model I threw together in Mathematica: [4]

The angle indicated by this model is roughly 60° ([5]), though the manner in which I modeled it does not allow precise measurement. This is my first post on Wikipedia (in fact, I registered just to post this), so I'm unsure as to the standard practice in these cases. I know citation or at least independent verification is likely needed for the location and axial tilt given, though, so I figured I'd post this here where more experienced wikipeople can handle it. --Michael Leuthaeuser 07:44, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

- Ideally, a source is required that is scientifically accurate and drawn from some kind of recognised authority. Unfortunately, any work you do, unless you publish it on a university site or other such credible source, would be considered original research by Wikipedia standards. I'm not particularly fond of the source I used for that info, so if you can locate a better one, I'd very much appreciate it. Serendipodous 07:57, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

- My calculations also show that it is close to 60°. If ψ is the angle between the north pole of the ecliptic and the north galactic pole than:

- ,

- where 27° 07′ 42.01 and 12h 51m 26.282 are the declination and right ascension of the north galactic pole, while 66° 33′ 38.6″ and 18h 0m 00 are for the north pole of the ecliptic. Ruslik_Zero 09:02, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

- So can we use it? Or do we need a citation to back up, not the calculations themselves, but the basis behind them? Serendipodous 13:28, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

- [6] I'm not incredibly at interpreting this programming script, but it seems to confirm that math, and it's from a .gov (NASA, at that). --Michael Leuthaeuser 17:22, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

- [7]Yet another source, this time published textbook, showing the same math. Neither list the angle explicitly, though.--Michael Leuthaeuser 17:43, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

- That's fine; if we have the math we can add it in a note and use these sources to back up the facts. We may also need a source to verify the math. Serendipodous 17:48, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

- I corrected the value in the article. Ruslik_Zero 13:10, 8 August 2010 (UTC)

- That's fine; if we have the math we can add it in a note and use these sources to back up the facts. We may also need a source to verify the math. Serendipodous 17:48, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

- So can we use it? Or do we need a citation to back up, not the calculations themselves, but the basis behind them? Serendipodous 13:28, 1 August 2010 (UTC)

Depiction of planets inadequate

It seems poor that, on the Mother of All Online Encyclopedias Anyone Can Edit, such a poor visual rendering of the planets is given. It is inadequate, for example, to convince one that the 'Dwarf Planets' are indeed dwarfish (an impolite way, incidentally, of saying notably small). What does come out from the picture is, in fact, that two of the planets are noticeably gigantic, and I refer here not to the 'gas giants,' which give rise to a further problem: having grasped the idea that the 'gas giants' are deceptively large, being composed mainly of gas, it seems necessary to present the viewer with a clear visual impression of the discrepancy between the planets' volume and that of their solid cores - this the diagrams fail to do. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 79.78.35.71 (talk) 18:43, 1 September 2010 (UTC)

- This an article on the overall "Solar System" and not an article on "Planet#Internal_differentiation" or gas giants. I am not sure we need to diagram the general internal structure of the gas giants in a general solar system article. It is always difficult to put any known dwarf planet on the same scale that shows the gas giants.

- I would never call Venus and Earth gigantic. If you strip away the atmospheres of all the planets, I am quite confident the gas giants would have cores at least as large. Science still does not known as a fact the exact size of the cores of the gas giants. How do you define the core of a gas giant in comparison to a small planet like Earth with a thin atmosphere? (Yes, size matters.) On Earth there is a very obvious dividing line between the mantle and the atmosphere, but on a gas giant there is only a soupy mixture that gets denser as you approach the center of the planet. -- Kheider (talk) 19:23, 1 September 2010 (UTC)