Talk:Gothic language/Archive 2

| This is an archive of past discussions about Gothic language. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

| Archive 1 | Archive 2 |

PGmc. [z]

The article currently reads:

Proto-Germanic *z remains in Gothic as z or is devoiced to s. In North and West Germanic, *z > r. E.g. Gothic drus (fall), Old English dryre.

This is not quite true. Well, it's a little misleading, at any rate. I'm assuming at least some of the editors are aware of this, and that this has been simplified for the sake of accessibility. I don't know if those who have worked on this article are worried about making it more complicated than it might need to be. If this is the case, then perhaps a word other than drus should be used for an example? Because drus is typically reconstructed as (N.Sg.) *drusaz, not **druz. Besides this, in this particular case, the [z] has been deleted as a consequence of the EGmc. [z]-deletion rule, not as a consequence of the EGmc. obstruent devoicing rule (e.g. [z] > [s]). We know this because the stem vowel [u] is short, and [z]-deletion must have occurred prior to obstruent devoicing. Furthermore, PGmc. [z] undergoes more changes than just [z] > [s] (i.e. obstruent devoicing) in EGmc.: there's [z]-deletion and [z] > [r] as well (as in *ūz-rīsan > Gothic urreisan - which may be an areal change shared by NWGmc. under certain circumstances). Like I said, I understand if this has been omitted for the sake of simplicity. But it's kind of misleading as it stands. Thanks, --Aryaman (talk) 08:57, 16 November 2009 (UTC)

Clarification??

"Gothic is unusual among Indo-European languages in only preserving it for pronouns." found under the pronouns section. This is inaccurate, as other Germanic languages have dual pronouns. It's uniqueness is due to the retention of the verb conjugation ONLY for pronouns. Old Norse certainly had dual pronouns, just no conjugations other than singular and plural. If I were more eloquent I'd change this myself... —Preceding unsigned comment added by Retailmonica (talk • contribs) 23:09, 18 January 2009 (UTC)

- I changed part of this, as it's generally agreed that all the early Gmc. dialects had dual pronouns. I'm currently researching the conjugation systems as well. --Aryaman (talk) 09:06, 16 November 2009 (UTC)

Doesn't look like a gothic language source, but instead latin written in uncial see File:Codex Rehdigerianus.jpg. Rursus dixit. (mbork3!) 20:28, 24 January 2010 (UTC)

- So if you wonder why the entry disappeared from the list, it was me! Rursus dixit. (mbork3!) 20:30, 24 January 2010 (UTC)

I find it difficult to follow how you can conclude from the absence of Gothic in one page of the codex to the absence of Gothic in the codex as a whole. --dab (𒁳) 20:47, 25 January 2010 (UTC)

Grouping of Gothic POV

In particular, the following statement: "However, for the most part these represent shared retentions, which are not valid means of grouping languages." LokiClock (talk) 13:45, 20 November 2009 (UTC)

- What exactly is the problem with this? ---Pfold (talk) 14:14, 20 November 2009 (UTC)

- In the absence of any response to my request for clarification, and since the point complained of is a fundamental tenet of historical linguistics, I am removing the POV flag. --Pfold (talk) 23:32, 24 January 2010 (UTC)

I think the statement objected to was the claim that the features are, in fact, shared retentions. This is a matter of attributing the views to whatever scholars hold them. Since the article already states that the "the so-called Gotho-Nordic Hypothesis" is a minority opinion I don't really see the problem. But it would be useful to have a bunch of names associated with the minority view, if possible recent support of the hypothesis because otherwise it would appear to be not so much a minority as an obsolete view. --dab (𒁳) 20:43, 25 January 2010 (UTC)

- The "Gotho-Nordic" connection hasn't seen much in the way of support since the late 60's. If names are needed, W.P. Lehmann (The Grouping of the Germanic Languages, 1966), H.F. Rosenfeld, (Zur sprachlichen Gliederung des Germanischen, 1954), and V. Schirmunski (Über die altgermanischen Stammesdialekte, 1965) would be the ones to include. The more recent mentions I've come across are made more as a historical footnote for the sake of completeness than for the purpose of presenting it as a viable hypothesis. Cf. H.F. Nielsen (1995) "Methodological Problems in Germanic Dialect Grouping" in Marold, E. (Ed.) Nordwestgermanisch pp. 115-123. --Aryaman (talk) 21:36, 25 January 2010 (UTC)

Passive Voice exclusivity?

"Gothic retains a morphological passive voice inherited from Indo-European, but unattested in all other Germanic languages..."

I'm not saying I'm a language expert, but I'm very sure that Swedish has a passive voice as well.

He took the flask = Han tog flaskan.

The flask was taken by him = Flaskan togs av honom.

Isn't this a morphological passive voice as well? I'm just saying. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 81.216.64.210 (talk) 19:42, 9 April 2011 (UTC)

- It is, but as far as I understand, the Swedish form is an independent, late innovation. The Gothic form is the only one that had been inherited directly from Indo-European. Fut.Perf. ☼ 19:47, 9 April 2011 (UTC)

- The Swedish passive originates from a combination of the verb with the reflexive pronoun. togs is etymologically really tog sig. In Old Norse the form was still tóksk, which is much more recognisable. CodeCat (talk) 13:34, 10 April 2011 (UTC)

This is correct for most of the cases, but this is mostley just contractions of verbs who have natural reflexive pronouns. With the passive, it wouldn't be possible to use the reflexive pronoun in a rewrite.

Han älskas -> Han blir älskad -> Han älskar sig.

He is being loved -> He is being loved -> He loves himself.

As you can see, they have two different meanings. I'm sure you are right, but can you say with 100% certainty that you are not bunching two different grammatical phenomenons together, just because they look alike (-s ending)?

Don't want to be flaming and stuff, just want to make sure there aren't any misunderstandings. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 81.216.64.210 (talk) 17:45, 10 April 2011 (UTC)

- You're quite right of course that the "sig" reflexive and the "-s" passive today are distinct constructions with different meanings, but it is apparently still the case that the one emerged out of the other historically (a process of grammaticalization). I'm not an expert on Skandinavian languages, but from what I remember reading, I believe the explanation CodeCat gave is indeed the generally accepted one. Fut.Perf. ☼ 18:11, 10 April 2011 (UTC)

Thank you for the explanation! I learned something new now :)--81.216.64.210 (talk) 00:52, 11 April 2011 (UTC)

Misinterpretation of a source?

In the section History and evidence we read "He [Walafrid Strabo] also refers to the use of Ulfilas' bible in a region probably around Lake Constance", which is obviously a misinterpretation of the same text, which is already commented in the previous sentence (there are no other references about Gothic language in his text, as "he also refers" appears to imply). Walafrid Strabo unambiguously refers to the use of Gothic language around the town of Tomis in Scythia: "didicimus apud quasdam Scytharum gentes, maxime Thomitanos, eadem locutione divina (i. e. the language of the Gothic translation of the Bible) hactenus celebrari officia" (De exordiis et incrementis quarundam in observationibus ecclesiasticis rerum, chapter 7); it is true that the town was renamed Constantia (modern Constanţa in Romania), but that has certainly nothing to do with the Lake Constance. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 85.130.29.103 (talk) 15:55, 4 September 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed, I can't find anything about Lake Constance here. I've tagged the claim as dubious. --Florian Blaschke (talk) 00:55, 9 December 2011 (UTC)

From the future?

The article refers to a dictionary in the Ottoman court and says "These terms are from nearly a millennium later and are therefore not representative of the language of Ulfilas" ... a millennium later would place the dictionary in 2500 - 2600 CE. I think that the article may mean a millennium earlier. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 206.47.180.174 (talk) 16:23, 10 February 2011 (UTC)

- Nah, what is meant that the Crimean Gothic materials are from nearly a millennium later than the Gothic texts from Late Antiquity. --Florian Blaschke (talk) 00:58, 9 December 2011 (UTC)

Innovations

I came to this article for a list and discussion of featrues for which Gothic is less conservative than other Germanic languages. (From the article on proto-Germanic I find e1 and e2 are not distinguished in Gothic, but perhaps there are more / better examples.) Since the article does include a good discussion of Gothic archaisms which are lost in all other Germanic languages, it would be very nice to include a discussion of innovations also. I would be most grateful. Tibetologist (talk) 14:19, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

- It's hard to make a clear distinction when it comes to innovations. Because Gothic is so much older than the other attested Germanic languages, it's naturally more archaic and preserves more older features, so that it's not always easy to see which features are retentions that were lost in all other languages, and which are innovations. It's quite likely that many archaic Gothic features also still existed in for example Frankish or Proto-Norse which were spoken at the same time as Wulfilas's Gothic. CodeCat (talk) 18:20, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

Crimean Gothic dating

Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq met two speakers of Crimean Gothic in his stay in Istanbul in around 1560. It says, in the History section. Surely this indicates a later date for the survival of the language than the early 9th C mentioned in the lead paragraph? If two speakers could be found in the 1550s or 60s, surely there must have been a pool of speakers through the intervening centuries. Even if these were the last two, a language couldn't have survived for five hundred years passed down through two people per generation. Peridon (talk) 17:51, 31 March 2013 (UTC)

- Crimean Gothic is no more Gothic than French is Latin. It has enough in common, and there's enough historical circumstantial evidence to make descent from Gothic the most plausible guess, but there's nothing sure about Crimean Gothic. It's a miracle that we know as much as we do, but it's not much. Chuck Entz (talk) 03:17, 27 July 2013 (UTC)

Pronunciation of ai, au, e, o

Something that has always bothered me is the standard interpretation of ai, au as mid-open and e, o as mid-close. To me this doesn't really make much sense, because Proto-Germanic ē and ō were mid-open to start with. While it's possible that they became more closed in Gothic, there is also the fact that i before r or h is spelled ai, and likewise for u becoming au. This makes more sense to me if ai and au denote mid-close vowels, since the phonetic 'distance' isn't as great. The same applies to the spelling au for Germanic ū before a vowel, as in bauan. And Latin sources of the time write au as o later on (ostrogoths?), which shows that these diphthongs were being lost in Gothic.

I realise this is a lot of original research, so what I would really like to see is a bit more information on why the spellings are interpreted the way they are in this article. Some sources would be nice too... CodeCat (talk) 12:57, 30 March 2011 (UTC)

- Joseph Wright in his Gothic Grammar was perhaps one of the first to assume that at least some instances of ai and au are mid-close, and that ē and ō are mid-open. I don't know what his reasoning was for the closeness and openness. — Eru·tuon 13:51, 30 March 2011 (UTC)

- Wright may have considered other evidence, but his explicit justification for identifying the close vowels is that scribes (particularly w scribe working of Luke) occasionally wrote 𐌴𐌹 where 𐌴 would be expected, and 𐌿 where Ꝣ would be expected. This confusion is presumably not found with the other long vowels represented as 𐌰𐌹 and 𐌰𐌿. DavidCrosbie (talk) 11:31, 28 July 2013 (UTC)

- I don't think there's any doubt that interpretating of the diphthong spellings is an unresolved issue. But I don't see any problem in principle in the diphthong spelling representing a more open vowel, rather the opposite - after all the monophthongisation of /ai/ is naturally going to involve raising, but raising the first and stronger element /a/ *past* an existing open /e:/ is highly implausible (how come they didn't merge?). In fact the monophthongisation and the raising of /e:/ are readily seen as a chain shift.

- Is it really unresolved? Writing in 1910, Joseph Wright admitted that he had "followed the usual practice of regarding each of the digraphs ai, au (printed ái, aí, ai; áu, aú in this book) as three different sounds" but goes on to rubbish the idea, concluding "It seems almost incredible that a man like Ulfilas, who showed such great skill in other respects, should have used ai for a short open e, a long open ǣ and a diphthong; and au for a short open o, a long open ǭ and a diphthong." The idea of surviving diphthong sounds in Gothic would appear to be a nineteenth century doctrine which Wright retained only as a convenient fiction for pedagogic purposes. Wright also notes that Ulfilas regularly used 𐌰𐌹 to represent Greek αɩ — which by that time represented a monophthong. DavidCrosbie (talk) 11:31, 28 July 2013 (UTC)

- I don't see anything wrong in leaving the passage as it is. But if someone felt like reviewing the literature on this issue, and expanding the presentation, I'm sure it would be useful. --Pfold (talk) 21:22, 30 March 2011 (UTC)

- Someone has added more pronunciations down the bottom of the article, which makes me wonder about this again. I still don't find the article's current state very convincing. It says that it's assumed that ē and ō are mid-close, and that ai and au are mid-open, yet fails to say why. The short e of Proto-Germanic is somewhat undeterminate, but probably close since it merged with i quite often. Long ē and ō were definitely open, as ō had been raised from ā not long before, and ē ended up merging with ā in Northwest Germanic. Furthermore, it's notable that final shortening of ē and ō gave short a in Gothic alone, whereas in West Germanic ō shortened to a high vowel u, and in North Germanic final ē and ō both became high, i and u. So Gothic arguably gives the most evidence for these being low-mid vowels in Gothic itself. I have noticed, though, that ai and au tend to be used to represent short e and o in Latin and Greek borrowings, so what do we know about the phonology of those languages? CodeCat (talk) 20:32, 29 April 2013 (UTC)

The Phonology section — at least the part relating to vowels — calls for a radical overhaul. Of course, phonology has two distinct meanings in Linguistics, but surely this section should be about the phonemic inventory of Gothic, not the sound changes from Common Germanic. (Although there's no reason not to treat the phonological history in a different section.) The questions to be addressed are: How many short vowels? How many long vowels? This is tied up with the question of digraphs — which surely must be discussed in relationship to the values of digraphs in Byzantine Greek. A recent textbook The Germanic Languages by Wayne Harbert summarises the vowel system thus:

- Three short vowel phonemes /i/, /u/,/ a/ but with two important allophones [ɛ], [ɔ]

- Five long vowel phonemes /iː/, /uː/, /eː/, /oː/, /aː/ with two sounds ɛː and ɔː which may be allophones or phonemes, depending on how one interprets the digraphs <ai> and <au>.

I'm trying to work out the argument behind this analysis. As the previous section starts with Gothic letters and attempts to assign sound values, this section should take the sound values as a starting point proceeding from phonemes to allophones to alphabetic representations.

I haven't seen any justification for diphthong phonemes in Gothic.

The transcriptions don't have to be strictly phonemic. Even if ɛː and ɔː are considered allophones, it would still be useful to include them, provided that it can be argued that they are consistently distinguished from eː and oː in their orthographic representation. DavidCrosbie (talk) 02:32, 28 July 2013 (UTC)

- I think it's reasonably clear that [ɛ], [ɔ] were no longer allophones by the time of writing. They appear in many loanwords, but more importantly -ai- also appears in the reduplicating syllable of class 7 strong verbs. That it appears there is itself puzzling (etymologically, it's Proto-Germanic -e-, so you'd expect -i- in Gothic), but the spelling is clearly -ai- in all cases, even where it's not allophonically expected. It is possible that this -ai- in fact represents a long vowel, which could have arisen in a lengthening process before the merging of short /e/ and /i/. There hasn't really been any discussion about that as far as I know, so there aren't any sources, but it should still be considered as a possibility. Still, the question remains what sound the spellings -ai- and -au- represent in the first place. The consensus seems to be that it was a low-mid vowel, but arguments for that conclusion are surprisingly scarce. To me, it doesn't seem so unreasonable that -e- and -o- were low-mid and -ai- and -au- were high-mid. CodeCat (talk) 10:54, 28 July 2013 (UTC)

- I've already quoted Wright's argument: Scribes occasionally confused 𐌴 and 𐌴𐌹 but not 𐌰𐌹 and 𐌴𐌹. (Also Ꝣ with 𐌿 but not 𐌰𐌿 with 𐌿—a separate but parallel argument).

- There's a more basic argument: See it from Ulfilas's point of view. There are two sounds eː and ɛː for which you have to choose Greek letters or digraphs. But these decisions are not to be taken in isolation. It's significant that you must also choose a letter or digraph for iː. Ulfilas chose to borrow the Greek digraph ει for iː, so it seems entirely natural that he should choose to borrow Greek epsilon for the closer of the two sounds eː and ɛː. He also chose alpha-based 𐌰 for the open a sound (and for the similar, more marginal aː sound). So is seems entirely natural that he should use a digraph incorporating 𐌰 (borrowed from the Greek digraph αι) for the more open of the two sounds eː and ɛː.

- I think you've allowed the use of the symbol e in the transcription of Common Germanic to influence your reasoning. But that symbol was ascribed by Jocob Grimm, or someone else of his generation. Ulfilas didn't know that e was a suitable symbol for Common Germanic. He didn't even know that there had been such a thing as Common Germanic. Phonological description can only be relative with a long dead language like Gothic and a reconstructed hypothetical language like Common Germanic. There were three heights in the phonology of hypothetical Common Germanic. The choice of symbol e for the front middle vowel is pretty obvious. It was even more obvious in Grimm's day before the invention of the cardinal vowel convention. Gothic, on the other hand exhibits four vowel heights. So there's not one vowel and vowel symbol between close and open. The choice of e in transcribing Gothic has entirely different significance from the choice in transcribing Common Germanic. The latter is a choice, barely a choice at all; the former is a serious choice between two distinct possibilities. DavidCrosbie (talk) 11:27, 29 July 2013 (UTC)

- I really don't understand your argument, or rather I don't see how it connects to my question. You say that Wulfila did not know what the original Proto-Germanic sound was, that's correct, and it's also true that he based his spelling on that of 3rd-century Greek. But Proto-Germanic ē was long open-mid [ɛː], and corresponds etymologically to the Gothic letter 𐌴; they appear in the same words so that there is a connection is indisputable. But why, then, does this article claim that 𐌴 represented a long close-mid [eː]? How do we know that 𐌴 was indeed pronounced close-mid, and that 𐌰𐌹 was open-mid? Why was 𐌴 not open-mid like it was in Proto-Germanic? If it was raised to close-mid in Gothic, what evidence is there for that? This article gives none, it just presents it as a matter of fact without any arguments. CodeCat (talk) 17:13, 29 July 2013 (UTC)

- I'm also a bit puzzled at your rather heavy reliance on very outdated sources. So far everything you've cited is at least a hundred years old, so it's not very reliable at all. Do you have anything up to date? CodeCat (talk) 17:24, 29 July 2013 (UTC)

- You ask why I cite Wright and Prokosch. Well, you've been asking for sources, and those are the only ones I have (apart from Wayne Harbett). Until last week, I'd barely looked at Prokosch in almost sixty years and I hadn't looked at Wright at all. When I did look, I found they made a lot more sense than they did when I was an undergraduate — because I've since studied and kept up my interest in linguistics. I'll be delighted if somebody replaces my citations with something more more up to date. Meanwhile, they're a whole lot better than nothing at all.

- I think you've allowed the use of the symbol e in the transcription of Common Germanic to influence your reasoning. But that symbol was ascribed by Jocob Grimm, or someone else of his generation. Ulfilas didn't know that e was a suitable symbol for Common Germanic. He didn't even know that there had been such a thing as Common Germanic. Phonological description can only be relative with a long dead language like Gothic and a reconstructed hypothetical language like Common Germanic. There were three heights in the phonology of hypothetical Common Germanic. The choice of symbol e for the front middle vowel is pretty obvious. It was even more obvious in Grimm's day before the invention of the cardinal vowel convention. Gothic, on the other hand exhibits four vowel heights. So there's not one vowel and vowel symbol between close and open. The choice of e in transcribing Gothic has entirely different significance from the choice in transcribing Common Germanic. The latter is a choice, barely a choice at all; the former is a serious choice between two distinct possibilities. DavidCrosbie (talk) 11:27, 29 July 2013 (UTC)

- You keep returning to this assertion "Proto-Germanic ē was long open-mid [ɛː]". To me that's just nonsense. The square brackets are totally unjustified. We can't know the phonetic nature of a reconstruction. All we can know is that the sound represented as ē in the literature would have been somewhere between the vowels represented as ī and ā. Gothic is different. There is evidence that there were two long vowels in the space between iː and aː.

- My one recent source, The Germanic Languages by Wayne Harbett goes much further in differentiating the phonology of Gothic from the phonology of Proto-Germanic. He states that the short-vowel repertoire reduces to three phonemes /i/, /a/, /u/ supplemented by two notable allophones [ɛ], [ɔ] created by breaking. The long-vowel repertoire is richer. In Harbett's judgement it reduced to five phonemes, but then — probably — grew to seven with the development of a further "height (or tenseness) distinction" in the mid-vowels. Probably, but not definitely according to Harbett, so he use the notation (/ɛː/), (/ɔː/) for the lower (laxer) pair. The high (tenser) pair are the vowels which trace back to Proto-Germanic. For these he uses the notation /eː/, /ɔː/ — i.e. they are unquestionably phonemes. Similarly the open pair are represented as /iː/, /uː/. The remaining long vowel is represented as (/aː/) not because of dubious phonemic status but because it is a rare, marginal sound in Gothic.

- The 𐌴 vowel was not "raised" as you put it. Its relative position was changed with the introduction of the 𐌰𐌹 vowel. DavidCrosbie (talk) 22:55, 29 July 2013 (UTC)

- It may be nonsense but it's a pretty clear consensus among linguists. In fact, earlier reconstructions of Proto-Germanic even posited [æː], which is lower still. There are definitely plenty of sources that give Germanic ē as [ɛː] or [æː] but you'd be hard pressed to find any that give a clear close-mid [eː]. So with that in mind, positing that Gothic ē was [eː] requires a change of ē from open-mid in Germanic to close-mid in Gothic. I'm not disputing that this may have happened, and there do seem to be plenty of sources that imply that it did. But if it did, where is the evidence? On what basis do these sources reconstruct Gothic ē as close-mid [eː] and ai as open-mid [ɛː], when it could also be the other way around? What makes one possibility more likely? The article is still sorely lacking in this regard. CodeCat (talk) 00:32, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- I realised that there's also another point that any explanation has to account for. If we assume that "ai" represented both short and long [ɛ], then that implies that there was also a change from Germanic [i] to Gothic [ɛ] at some point. While that's possible of course, it's not as likely as a change from [i] to [e] simply because they are phonetically closer together. As far as I can tell, bairan could be [beran] just as well as [bɛran]. CodeCat (talk) 00:38, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- Look, I realise I'll never know as much as you about Gothic but I do understand phonology. Phonology the modern discipline, that is. Unless you can demonstrate that there was more than one level of vowel articulation between iː and aː in Common/Proto Germanic, then your argument has no substance whatsoever. Whether you label a reconstructed sound as ē or ǣ is totally irrelevant from the point of view of modern phonology — unless, of course, you assert that the two existed simultaneously in the inventory of one language. Have you noticed that nobody else has attempted to engage with your argument? To the rest of the world it's just blindingly obvious that 𐌴 was chosen to represent a sound higher than the 𐌰𐌹 sound. I've tried to see any line of argument that might challenge this. There is none — apart from your bizarre belief that it's possible to identify a precise phonetic value of Germanic ē and the equally bizarre belief that this value must have persisted throughout the development of Gothic. I don't want to belittle your beliefs. I'm just saying that they're incompatible with the approach of modern phonology. When I was an undergraduate, Comparative Philology was a discipline seriously detached from Linguistics. Great, great scholars wrote things that the most humble linguist could easily pick holes in. The attempt to conflate the descriptive with the historical was challenged by the father of modern linguistics Ferdinand De Saussure: the synchronic is not the diachronic. It's possible to describe a sub-system such as a long vowel inventory at one point in time and at a subsequent point in time. It's possible to trace developmental links between items in one description to items in another. But when there is no correspondence — as with the 𐌰𐌹 and 𐌰𐌿 vowels — there is no link to trace. You have two radically different sub-systems: Common/Proto Germanic with three vowels and Gothic with four vowels. You just can't take data from the former as evidence in analysing the latter. Of course, if you've found evidence of a fourth vowel value in Proto-Germainic, then you have a serious case. DavidCrosbie (talk) 10:53, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- Why do you say that Proto-Germanic had only three vowel values? It's reconstructed with four short, five or six long vowels, and two overlong vowels: short a /ɑ/, e /e/, i /i/, u /u/, long ē /ɛː/, ē2 /eː/ (which was very rare), ī /iː/, ō /ɔː/, ū /uː/ and maybe ā /ɑː/ which Ringe argues must have existed, and overlong ô /ɔːː/ and ê /ɛːː/. There were also nasal varieties of many of these vowels either word-finally or before h. All of this is on the Proto-Germanic page and it's sourced, so I shouldn't need to argue about it, that's would be original research on your part. Said another way: if sources give specific values for these Proto-Germanic sounds, then it's original research to say it's "totally irrelevant" as this is not what the sources say.

- Three heights. That allows five or six long vowels and five or six short vowels — more of course for languages with nasal vowels and with systems such as central vowels or pairs of rounded/unrounded vowels, and the subsystem of what you term 'overlong' vowels. In the front of the PG long vowel subsystem there are three sounds. I choose to label them iː, eː, aː but other symbols would be equally valid, including the traditional ī, ē, ã or the proposed ǣ in place of ē — or, indeed, ɛ̄. What matters is not the symbol but the number, and the number of long vowels between iː and aː seems universally agreed to be one. In Gothic however, the number of vowels between iː and aː seems generally agreed to be two. The obvious symbols for two such vowels are e and ɛ. So the question arises: which sound was higher (tenser) and which more open (laxer)? The vowel stemming from PG e or the innovation which originated in a different sub-system, the diphthongs? Exactly the same argument applies to long vowels futher back between ū and ā. DavidCrosbie (talk) 18:55, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- The development of most of these vowels into Gothic is clear and not in dispute. Nasalised vowels merge with their non-nasal counterparts. Short e and i merge, and this merged phoneme develops lowered allophones before r and h. Long and overlong vowels merge, except word-finally. ē and ē2 also merge. ū is lowered before a vowel. What is not clear, though, is that when ai and au became monophthongs, they ended up at a lower position than ē and ō. You say that it's blindingly obvious, but you have not provided any evidence or sources to support your claim. CodeCat (talk) 14:52, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- Why do you say that Proto-Germanic had only three vowel values? It's reconstructed with four short, five or six long vowels, and two overlong vowels: short a /ɑ/, e /e/, i /i/, u /u/, long ē /ɛː/, ē2 /eː/ (which was very rare), ī /iː/, ō /ɔː/, ū /uː/ and maybe ā /ɑː/ which Ringe argues must have existed, and overlong ô /ɔːː/ and ê /ɛːː/. There were also nasal varieties of many of these vowels either word-finally or before h. All of this is on the Proto-Germanic page and it's sourced, so I shouldn't need to argue about it, that's would be original research on your part. Said another way: if sources give specific values for these Proto-Germanic sounds, then it's original research to say it's "totally irrelevant" as this is not what the sources say.

- Look, I realise I'll never know as much as you about Gothic but I do understand phonology. Phonology the modern discipline, that is. Unless you can demonstrate that there was more than one level of vowel articulation between iː and aː in Common/Proto Germanic, then your argument has no substance whatsoever. Whether you label a reconstructed sound as ē or ǣ is totally irrelevant from the point of view of modern phonology — unless, of course, you assert that the two existed simultaneously in the inventory of one language. Have you noticed that nobody else has attempted to engage with your argument? To the rest of the world it's just blindingly obvious that 𐌴 was chosen to represent a sound higher than the 𐌰𐌹 sound. I've tried to see any line of argument that might challenge this. There is none — apart from your bizarre belief that it's possible to identify a precise phonetic value of Germanic ē and the equally bizarre belief that this value must have persisted throughout the development of Gothic. I don't want to belittle your beliefs. I'm just saying that they're incompatible with the approach of modern phonology. When I was an undergraduate, Comparative Philology was a discipline seriously detached from Linguistics. Great, great scholars wrote things that the most humble linguist could easily pick holes in. The attempt to conflate the descriptive with the historical was challenged by the father of modern linguistics Ferdinand De Saussure: the synchronic is not the diachronic. It's possible to describe a sub-system such as a long vowel inventory at one point in time and at a subsequent point in time. It's possible to trace developmental links between items in one description to items in another. But when there is no correspondence — as with the 𐌰𐌹 and 𐌰𐌿 vowels — there is no link to trace. You have two radically different sub-systems: Common/Proto Germanic with three vowels and Gothic with four vowels. You just can't take data from the former as evidence in analysing the latter. Of course, if you've found evidence of a fourth vowel value in Proto-Germainic, then you have a serious case. DavidCrosbie (talk) 10:53, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- The 𐌴 vowel was not "raised" as you put it. Its relative position was changed with the introduction of the 𐌰𐌹 vowel. DavidCrosbie (talk) 22:55, 29 July 2013 (UTC)

- I didn't think you really believed that the 𐌰𐌹 vowel could have been higher than the 𐌴 vowel. Nobody else believes it because it's so preposterous. Why on earth would Ulfilas choose the 𐌴 symbol for the sound that was further from the 𐌴𐌹 sound? And the 𐌰𐌹 symbol for the sound that was further from the 𐌰 sound?

- Your account of PG vowels developing into Gothic vowels is phonology in the ancient sense that is no longer used because it isn't useful. Modern phonology tries to understand how systems develop. PG ē and au belonged in different sub-systems: the long vowel subsystem and the diphthong subsystem. In the run-up to Gothic, the former diphthong became an extra member of the long-vowel (monophthong) subsystem.

- It seems overwhelmingly likely that this happened before Ulfilas. Especially with his choice of 𐌰𐌹 — He would have had no way of knowing that Greek αι had ever represented a diphthong. OK, so Greek αυ wasn't a monophthong, but it had ceased to represent a diphthong.DavidCrosbie (talk) 18:55, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- Still, it's clear that Wulfila chose a lot of his spelling conventions based on those of Greek. Using 𐌴𐌹 to write a long [iː] was certainly one of those conventions, and another clear example is using 𐌲 to represent [ŋ]. He couldn't have based his choice of 𐌰𐌿 on Greek (because there it was becoming [af] rather than a long vowel), but for 𐌰𐌹 he probably was inspired by Greek. So what sound was αι in the Greek of the time? Was it higher than ε or lower? The page Koine Greek phonology shows that both were in fact homophones and had been already for hundreds of years before. So if he took those two writing conventions from Greek, he did not take their pronunciations as they are different in Gothic. That means that we have to derive the pronunciations of those two vowels from loanwords. What letters does Wulfila use to substitute for η [e] in Greek loanwords? And what about Latin, which he no doubt knew as well? The Latin of the time had ĕ [ɛ] and ē [e], length distinctions were probably disappearing (see Vulgar Latin). So what does Wulfila use for these two Latin sounds? CodeCat (talk) 22:15, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- It seems that neither of us has access to the latest scholarship on Byzantine Greek pronunciation, but both of us have seen an account to the effect that ε, η and αι were merged. This is unhelpful. It means that there were three vowel heights corresponding to Gothic four heights. So in this respect matching Gothic phonology to Greek presents the same problem as matching Gothic phonology to Proto-Germanic. Four into three doesn't go as we used to say in primary school arithmetic. For me the overwhelmingly convincing evidence is that Ulfilas's chosen vowels and digraphs had a visual resemblance to the symbols which were obvious choices for high and low vowels — that is to say ει and ου for high with α for low.

- • So what should Ulfilas use for eː, the higher of the two mid sound? Should he use αι , a symbol which bears no resemblance to the one used for the highest long vowel, namely ει? Or should he choose a symbol which is not just similar, but which actually comprises half of the digraph, namely epsilon? [I use the name rather than the symbol because in my default font there is too much similarity between U025B Latin small letter open E and U03B5 Greek small letter epsilon.]

- • By the same token what should he use for ɛː the lower of the two mid sounds? Should he choose epsilon, a symbol which bears no resemblance to the one used for the lowest long vowel, namely α? Or should he choose a symbol which is not just similar, but which incorporates it a half of a digraph, namely αι?

- • The argument is less strong for 𐌰𐌿, which incorporates elements of highest ου and lowest α. Even so, it seems not unreasonable to see it as parallel to 𐌴𐌹

- Your question about Latin is valid, but I fear there' will be no easy answer. Greek was the language of the Roman East. Latin was the language of the Roman West and the Roman Church. But Ulfilas's Church was not only non-Roam, it wasn't even Orthodox. And even if he knew some Latin, he wouldn't need to be literate in Latin. All the names of people from the East and West of the Empire could be read in and transcribed from Greek. I have better sources for Latin, though. I'll look them up and report if there's anything pertinent. DavidCrosbie (talk) 11:41, 31 July 2013 (UTC)

- Still, it's clear that Wulfila chose a lot of his spelling conventions based on those of Greek. Using 𐌴𐌹 to write a long [iː] was certainly one of those conventions, and another clear example is using 𐌲 to represent [ŋ]. He couldn't have based his choice of 𐌰𐌿 on Greek (because there it was becoming [af] rather than a long vowel), but for 𐌰𐌹 he probably was inspired by Greek. So what sound was αι in the Greek of the time? Was it higher than ε or lower? The page Koine Greek phonology shows that both were in fact homophones and had been already for hundreds of years before. So if he took those two writing conventions from Greek, he did not take their pronunciations as they are different in Gothic. That means that we have to derive the pronunciations of those two vowels from loanwords. What letters does Wulfila use to substitute for η [e] in Greek loanwords? And what about Latin, which he no doubt knew as well? The Latin of the time had ĕ [ɛ] and ē [e], length distinctions were probably disappearing (see Vulgar Latin). So what does Wulfila use for these two Latin sounds? CodeCat (talk) 22:15, 30 July 2013 (UTC)

- For what it's worth, I've got a picture of Late Latin phonology in the East on which two source — one fairly old, one quite recent — agree.

- • First, throughout Latin, there ceased to be separate long and short vowel systems. With the exception of a and aː, which merged, the four quantitative pairs became eight qualitative vowels: ɪ, i, ɛ, e, ɔ, o, ʊ, u

- • Next the eight vowels were reduced by mergers. In the East the result was i, ɛ, e, a, o, u. This means four heights at the front and three at the back. However, the symmetry is resolved if we include the one surviving diphthong au.

- (In the West, the mergers rested in five vowels — i.e. three heights: i, e, a, o, u. The sole surviving diphthong au did not immediately disappear but eventually merged with o in the Western Romance languages, except in parts of Southern France.) DavidCrosbie (talk) 17:20, 31 July 2013 (UTC)

- I understand what you are saying but I am trying to specifically relate the phonologies of the languages and not so much their spelling. There isn't enough information within Gothic itself to say whether ē was high or low compared to ai, and reasoning about Wulfila's logic in spelling is just pure speculation. It seems fairly likely that any loanwords from Greek or Latin into Gothic would have had to be adapted to Gothic phonology. So how do the Greek and Latin vowels appear in Gothic? Do Latin loanwords ever appear with ē in Gothic, or always ai? How is Latin ē (and the occasional oe) reflected in Gothic? In Old High German it tends to appear as ī, so do we find ei in Gothic, or ai or ē? CodeCat (talk) 01:52, 1 August 2013 (UTC)

- I can't find any evidence of Gothic absorbing Latin loan words. It's entirely likely that it never happened — in the stuff that was written down and has been preserved, that is. Greek seems quite straightforward: α→𐌰; ε→𐌰𐌹; ι→𐌹 or 𐌴𐌹, exceptionally→𐌰𐌹 in one word (Κυρηνιοϛ), sometimes consonant 𐌾 before vowel: ο→𐌰𐌿 in most contests but 𐌿 in final syllables, also 𐍉 in Ἐρμογενηϛ →𐌰𐌹𐍂𐌼𐍉𐌲𐌰𐌹𐌽𐌴𐍃, 𐌿 in Ίεροσαλυμα→ 𐌹𐌰𐌹𐍂𐌿𐍃𐌰𐌵𐌻𐍅𐌼𐌻; υ→𐍅 (ignored by modern scholars), but 𐌰𐌿 in 𐍃𐌰𐌿𐍂=Συροϛ; η→𐌰𐌹; ω→𐍉 usually, but 𐌻𐌿 in Λωιϛ→𐌻𐌰𐌿𐌹𐌳𐌾𐌰 and Τρῳαϛ→𐍄𐍂𐌰𐌿𐌰𐌳𐌰, also 𐌿 in 𐍂𐌿𐌼𐌰 [Could this be from the name as heard in Latin?], αι→𐌰𐌹, α+ι→𐌰𐌴𐌹 as in Βηθσαιδα→𐌱𐌴𐌸𐍃𐌰𐌴𐌹𐌳𐌰; ει→𐌴𐌹; ευ→𐌰𐌹𐍅; ου→𐌿.

- Your dismissal of arguments from spelling is misguided. Almost everything we know about recovered pronunciation is based on the way cognate sounds were eventually spelled. OK, there are animal noise words, and some contemporary descriptions of Latin and Greek pronunciation. And in languages like English, there are arguments from rhyme. But those descriptions of of a much earlier stage in both languages. And while poetry supplies evidence of vowel length, there is no rhyming evidence.DavidCrosbie (talk) 10:46, 1 August 2013 (UTC)

- I exaggerated the anachronism of Greek descriptions, some of which are closer to Ulfilas's time. But Greek is not the problem. I should also have mentioned spelling mistakes and inconsistencies as evidence. Ana argument made by Wright is based on apparent confusion of 𐌴 and 𐌴𐌹 , but not of 𐌴 and 𐌰𐌹. Studies of Late Latin pronunciation make much of a list of common spelling mistakes.

- Arguments based on spelling may be hypothetical but they are based on real data. If you argue from the phonology of another historical language, it's hypothetical based on hypothetical. And if you base it on the phonlogy of a reconstructed language it's based on extremely hypothetical quasi-data. DavidCrosbie (talk) 11:40, 1 August 2013 (UTC)

IPA Transcription

The disputed transcription of the Lord's Payer is notationally fine. Every symbol used is in the repertoire of the 1989 Kiel revision of the alphabet. All that is needed is to check the actual transcription, which requires a Gothic specialist rather than a phonetician.

However, the use of superscript ⁱ and ᵁ in the Alphabet and transliteration section doesn't seem orthodox to me. DavidCrosbie (talk) 11:44, 27 July 2013 (UTC)

I suggest replacing iᵁ, aᵁ , aⁱ with iu, au, ai (or similar). DavidCrosbie (talk) 13:19, 27 July 2013 (UTC)

- There is a discussion above about the phonetic realisation of these digraphs. It seems quite certain that they were not /ai/ and /au/, but that they had become long monophthongs. But what pronunciation they have is not quite clear to me. CodeCat (talk) 16:49, 27 July 2013 (UTC)

- If it's the phonetic realisation, then it has no business within slants. And even if you put in within square brackets, it still doesn't use current IPA symbols. DavidCrosbie (talk) 22:30, 27 July 2013 (UTC)

- In any case, you can't have it both ways. If the values are monophthongs, then the diagram in the article illustrating diphthongs must be deleted. As long as that diagram is maintained, it calls for revised IPA symbols. DavidCrosbie (talk) 22:49, 27 July 2013 (UTC)

- For those not familiar with slant and square bracket conventions, the slants enclose phonemic transcription, which does not seek to represent those variations in pronunciation that make something a different word. Exact representations of pronunciation are phonetic transcription enclosed within square brackets.

- Transcription is (usually) very different from transliteration, so the reference to IPA transliteration is confusing, possibly also confused. DavidCrosbie (talk) 22:49, 27 July 2013 (UTC)

There's nothing wrong with aⁱ, iᵘ, etc. That's standard IPA usage, and it matches the vowel chart. I deleted the 'expert' tag, as that's not likely to get the kind of attention we need. — kwami (talk) 22:55, 7 September 2013 (UTC)

Gothic language news

Hello there. I started a Gothic language news website and I wonder if anyone has objections if I add it to the links? It isn't ancient Gothic but rather the same as modern Hebrew, a modern use of an ancient language but it may be relevant to people reading about Gothic or interested in it. Bokareis (talk) 21:37, 19 September 2014 (UTC)

- Sorry, but the external links are not supposed to be used for editors to promote their own websites. In any case, since your site is not devoted to the subject of this article, it's not relevant. --Pfold (talk) 13:45, 20 September 2014 (UTC)

- I only agree with the promotion part. I don't really get what you say here though: In any case, since your site is not devoted to the subject of this article, it's not relevant.. I recommend to remove this complete article. My website uses only Gothic words and morphology and it also uses the Gothic script. As it isn't relevant to Gothic, this wikipedia article is complete fantasy about Gothic because my news website also has the morphology and words described in this article while it's not relevant according to you. Bokareis (talk) 22:22, 26 September 2014 (UTC)

- Is it ok if I remove the link to Bagme Bloma, because Bagme Bloma just as my website is a modern construction of Gothic and according to your intepretation it is not relevant to Gothic, so it should be removed. Bokareis (talk) 22:24, 26 September 2014 (UTC)

- I only agree with the promotion part. I don't really get what you say here though: In any case, since your site is not devoted to the subject of this article, it's not relevant.. I recommend to remove this complete article. My website uses only Gothic words and morphology and it also uses the Gothic script. As it isn't relevant to Gothic, this wikipedia article is complete fantasy about Gothic because my news website also has the morphology and words described in this article while it's not relevant according to you. Bokareis (talk) 22:22, 26 September 2014 (UTC)

Modern publications in Gothic worth to mention?

Several books have been published in Gothic in 2015, e.g. Im leitila (Bin ich klein), is it worth to mention such publications which are made in cooperation with linguists in the Gothic language? Bokareis (talk) 23:38, 14 December 2015 (UTC)

- Can it be shown that these recent books are notable in relation to the subject of the article? I don't think it adds much to the topic. HighInBC 17:03, 20 December 2015 (UTC)

- Well, they are in Gothic and translated or corrected by linguists like professor L. De Grauwe from the university of Ghent but as they are relatively unknown they aren't mentioned in anything like a journal or boook. I have personal contact with a respected Germanicist, he shows interest for the Gothic revival, maybe I should ask him if he can do something with it. Bokareis (talk) 23:15, 20 December 2015 (UTC)

- It does not seem relevant to me. A brief mention that the language is still in some use may be called for but not specific examples, not unless a specific example is specifically notable in the subject of Gothic language. That being said I am happy to hear other people's opinions. HighInBC 15:26, 22 Decem

ber 2015 (UTC)

- Not relevant, I would say: modern texts written by a handful of individuals who have "learnt" the language from grammars, can never come into contact with native speakers, can have no "fluency" in the language, are not part of a wider movement to revive a dead language, and have no influence on the study of Gothic. --Pfold (talk) 16:23, 23 December 2015 (UTC)

- Well said. Fut.Perf. ☼ 16:33, 23 December 2015 (UTC)

- Then again, Old English does have a very short section on this, and it doesn't hurt. These things ARE fun, and they are related to the work of serious scholars. A sentence would be OK. Definitely not a discussion of individual texts though. --Doric Loon (talk) 17:45, 23 December 2015 (UTC)

- But the crucial difference is, the Old English article actually has a reliable source to cite about that revival stuff (albeit a rather dismissive one). Fut.Perf. ☼ 19:40, 23 December 2015 (UTC)

- I just see the discussion here again. Instead of these books, I added a section about the use of Gothic in Romanticism. I agree with you that the modern works are relatively too unknown, but both Tolkien and Maßmann are quite well known Romanticists and there doesn't seem anything wrong to me with including this section as they aren't just someone who studied the grammar, but linguists with an important role in the Gothic language, Maßmann as publisher of the Skeireins and Tolkien as the one who used names inspired by Gothic in a world-famous fictional work, Lord of the Rings. Might it be interesting to include an analysis of the Gothic-inspired names in Lord of the Rings? Bokareis (talk) 13:42, 5 January 2016 (UTC)

- But the crucial difference is, the Old English article actually has a reliable source to cite about that revival stuff (albeit a rather dismissive one). Fut.Perf. ☼ 19:40, 23 December 2015 (UTC)

- Then again, Old English does have a very short section on this, and it doesn't hurt. These things ARE fun, and they are related to the work of serious scholars. A sentence would be OK. Definitely not a discussion of individual texts though. --Doric Loon (talk) 17:45, 23 December 2015 (UTC)

- Well said. Fut.Perf. ☼ 16:33, 23 December 2015 (UTC)

The Gothic language is Germanic Norse

That language Gothland originated in what is now Sweden, no other descends eastern German language and comes directly from the source of that family. It is Nordic! --Derekitou (talk) 05:15, 31 January 2016 (UTC)

- No. It is not. A person speaking a Nordic language does not understand Gothic. ·maunus · snunɐɯ· 05:25, 31 January 2016 (UTC)

Alice in Gothic and Adeste Fideles

I added Adeste Fideles to Use of Gothic in Romanticism and the modern age for two reasons, Adeste Fideles is a well-known song and the translation is done by Bjarne Simmelkjær Hansen who is a professor and should be authorative enough to be taken seriously. Also there's a wikipedia article about Roots of Europe so it's no unknown project which doesn't deserve to be mentioned.

I 'd like to ask if it's worth mentioning Balþos Gadedeis Aþalhaidais in Sildaleikalanda, the Gothic translation of Alice? There are some problems with the text and I 'm not sure if it's well-known or authorative enough to be mentioned, the books by Phillip Winterberg were rejected e.g. Bokareis (talk) 20:25, 29 September 2016 (UTC)

External links modified

Hello fellow Wikipedians,

I have just modified one external link on Gothic language. Please take a moment to review my edit. If you have any questions, or need the bot to ignore the links, or the page altogether, please visit this simple FaQ for additional information. I made the following changes:

- Added archive https://web.archive.org/web/20050324024538/http://reimar.de/gotisch.html to http://www.reimar.de/gotisch.html

When you have finished reviewing my changes, you may follow the instructions on the template below to fix any issues with the URLs.

This message was posted before February 2018. After February 2018, "External links modified" talk page sections are no longer generated or monitored by InternetArchiveBot. No special action is required regarding these talk page notices, other than regular verification using the archive tool instructions below. Editors have permission to delete these "External links modified" talk page sections if they want to de-clutter talk pages, but see the RfC before doing mass systematic removals. This message is updated dynamically through the template {{source check}} (last update: 5 June 2024).

- If you have discovered URLs which were erroneously considered dead by the bot, you can report them with this tool.

- If you found an error with any archives or the URLs themselves, you can fix them with this tool.

Cheers.—InternetArchiveBot (Report bug) 15:45, 21 October 2017 (UTC)

rendering support

The article talks about rendering support for IPA symbols but not for Gothic letters! --Espoo (talk) 21:42, 3 December 2017 (UTC)

Gotho-Nordic

Gotho-Nordic redirects to the Classification section of this article. However, I wonder whether it shouldn't have its own article, to parallel the article about Northwest Germanic, which is the main alternative hypothesis. Gotho-Nordic is also part of the discussion of the Nordic language, not just a Gothic matter. Thoughts? --Pfold (talk) 11:39, 20 December 2017 (UTC)

- I think this subgrouping has been completely abandoned, and hence does not need a separate article.·maunus · snunɐɯ· 13:00, 20 December 2017 (UTC)

Iberian manuscripts claim

From the article:

The language survived as a domestic language in the Iberian peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal) as late as the eighth century. Gothic-seeming terms are found in manuscripts subsequent to this date, but these may or may not belong to the same language.

It's not apparent which manuscripts this is referring to. If it's in reference to Gothic-origin personal names, this should be stated. Another possibility is that of legal terms (cf. Vandalic Baudus among others). --Uchuflowerzone (talk) 14:06, 19 January 2018 (UTC)

Hello, i have one source for this article, is it acceptable on this article?

Hi, i was looking for reliable sources (books,newspapers and some websites) and i found this:

https://books.google.se/books?id=ViXFDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA1092&lpg=PA1092&dq=gutisko+razda&source=bl&ots=JbJKag_Prc&sig=qFAtOAvxSwsRyGEf19UfI1wml2g&hl=sv&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwizquXU4u7ZAhWrApoKHeaWCqMQ6AEwA3oECAUQAQ#v=onepage&q=gutisko%20razda&f=false

Is it ok to use it on the article as it’s a autonom by the Goths for their language. (Remember use Template:Agree or Template:Disagree if you agree this or you are against it.) newroderick895 (talk) 16:58, 15 March 2018 (UTC)

- But if this is genuine, why does the text not ell us which original Gothic source it comes from? Especially since this book is self-evidently self-published. A non-peer-reviewed claim based on no cited evidence? Worthless, I'm afraid. If any such claim were valid, it would be in every handbook on Gothic, not just in something written by a non-specialist published last year. --Pfold (talk) 17:27, 15 March 2018 (UTC)

- Evidently not a scholarly work; the references list at the end points to Wikipedia as a main source. Fut.Perf. ☼ 17:40, 15 March 2018 (UTC)

- But if this is genuine, why does the text not ell us which original Gothic source it comes from? Especially since this book is self-evidently self-published. A non-peer-reviewed claim based on no cited evidence? Worthless, I'm afraid. If any such claim were valid, it would be in every handbook on Gothic, not just in something written by a non-specialist published last year. --Pfold (talk) 17:27, 15 March 2018 (UTC)

Shouldn’t it be Google Scholar or i just put the wrong source? newroderick895 (talk) 18:29, 15 March 2018 (UTC)

Indian names

I see that the Indian names as mentioned by Krause are added. This is most likely an example of peculiar theories by 19th century linguists and linguistics because barely any linguist nowadays takes the theory of the names in an Indian inscription to be Gothic seriously. I think it should stay mentioned that Krause had this theory, but something should be added to this with a right source that the idea that this Indian inscription would represent Gothic names is not very likely and rather has names which are misinterpreted as being Germanic in origin on it. Bokareis (talk) 18:34, 3 July 2019 (UTC)

- @Bokareis: You added this yourself back in the day. Where in his Handbuch does he mention it, by the way? I can't find it, and the note does not mention a page. I'd like a look at it, even if it indeed probably is nonsense. — Mnemosientje (t · c) 16:21, 22 October 2019 (UTC)

- Nevermind, I found the original article by Sten Konow. Definitely looks like nonsense. — Mnemosientje (t · c) 16:31, 22 October 2019 (UTC)

Audio of Lord's Prayer does not match transcription

For example [w] is usually realized as [v], and consonant gemination is ignored. Grover cleveland (talk) 07:33, 16 February 2020 (UTC)

- @Grover cleveland: Well observed, and yes, there are a lot of other issues: long vowels instead of short vowels in several instances, syllable-final h is not pronounced: [ˈwiːhnɛː] and [ˈkʷimɛː] sound like [ˈwiːnɛː] and [ˈkʷiːmɛː]; odd stress placements in [ˈθiu̯ðinasːus] (sounds like [ˈθi:u̯ˈθi:nasus]), [ˈhimina jah] (sounds like [himiˈna: ja:]), [ˈunsarana ˈθana] (sounds like [ˈunsaˈra:na ˈθa:na]). Since it is more misleading than helpful, I will delete it, and insert it here for verification of our issues. –Austronesier (talk) 08:36, 16 February 2020 (UTC)

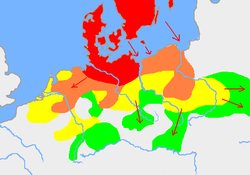

Wrong map?

I'm a bit surprised to see this map in the article, as it doesn't seem to have any evident connection with Gothic, whose area is surely much further south, from Spain to Romania? Maybe somebody could explain, or else remove the map. Chiswick Chap (talk) 19:37, 28 April 2021 (UTC)

- Seems accurate to me for the given time span. Rua (mew) 19:47, 28 April 2021 (UTC)

- The Goths didn't get to Spain until several centuries after the period of the map, which is, incidentally, from a reputable source.--Pfold (talk) 20:37, 28 April 2021 (UTC)

- Many thanks for the replies. It would be nice to have the source cited in the map's caption. Chiswick Chap (talk) 08:46, 29 April 2021 (UTC)

- ^ Kinder, Hermann (1988), Penguin Atlas of World History, vol. I, London: Penguin, p. 108, ISBN 0-14-051054-0.

- ^ "Languages of the World: Germanic languages". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago, IL, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1993. ISBN 0-85229-571-5.

Influences on Catalan erased completely

I added information about influences on the Catalan language (vocabulary, grammar and phonetics).

This has been completely removed because it “needs better sourcing”.

I’d like to know what kind of sources would be needed. This has been my first edit on Wikipedia and I would like to be helpful here.

On a side note, there are already some influences on Portuguese vocabulary in there, without any sources. Wouldn’t it make sense to at least have left the vocabulary influences on Catalan that I added?

When it comes to the grammar, what kind of sources would be needed? I linked to Wikipedia’s page on Gothic declension and I would like to link a page on Catalan plural formation but it sadly doesn’t exist. I already added however a source for it that I found online, though it being a website might not be good enough.

Furthermore the information that I added about loss of final-word vowels from Latin to Catalan being attributed to Gothic has backed with a source coming from a linguistic specialised in Catalan language. I’d like to know why this wasn’t good for the article.

Again, this was my first edit and I would really appreciate any help/guidance on the matter, so I can hopefully be of any help myself for Wikipedia. Isarn Falb (talk) 09:14, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- I don't know enough about the subject to answer the question but I will ping @Future Perfect at Sunrise: and hopefully they can give you some constructive device. Welcome to Wikipedia. HighInBC Need help? Just ask. 09:19, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- We could do with something on loans in Romance with wider scope - this amount of detail on a single Romance language is disproportionate here, especially given we have no coverage of much more populous Romance languages. There is a section on Gothic in Influences on the Spanish language, which could be summarised (though with improved sourcing). The standard work on the subject is Ernst Gamillsheg's 3-volume Romania Germanica Sprach- und Siedlungsgeschichte der Germanen auf dem Boden des alten Römerreichs (Vol 2 covers Gothic loans), but I'm sure there's plenty of more recent material online. The key with an online source in this context is whether it's been peer-reviewed or the author at least has some demonstrable academic qualification. --Pfold (talk) 11:06, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

Thanks for the feedback, really appreciate it. I’ll keep your advice in mind when dealing with online sources.

Would it be a good idea by the way to add to this section a few words in Spanish and link to the main article you mention?

And about the content I wanted to add, do you think it would be a good idea to create a page about influences on the Catalan language, where this kind of information could be added? The language has a lot of Gothic vocabulary in it and its phonetic evolution from Vulgar Latin was also influenced by the Visigoths (this, as I mentioned, can be sourced from a linguist from Vanderbilt University specialised in Catalan). Influences from other languages could also be added to that page. Isarn Falb (talk) 11:21, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- I share Pfold's objection that the section as added was probably given exaggerated weight to Catalan as opposed to other Iberian Romance languages. I don't know enough about the comparative degrees of influence on each, but if there is a case to be made that Catalan was somehow significantly more deeply influenced than other Romance languages in the area, we'd need much better sourcing for that than somebody's blog post. Also, as far as I could see, the second point that was added, about Gothic influence on vowel apocope, sourced to the Rasico (2004) paper, that source didn't actually support the claim as stated, as it linked it (tentatively) to Germanic in general, naming both Frankish and Gothic as possible influences, not singling out Gothic as the source. Finally, the other point, about the supposed parallel regarding -ns plurals, that was only sourced to that amateur(?) blog [1] and is linguistically fishy, to say the least. If that's a serious hypothesis, we'll need professional, published linguistic sources proposing it. I've done some research work in the area of historical contact linguistics myself, during my time in academia, and I can safely say it takes a lot more than what we see in that blog to make a successful case for a structural borrowing scenario like that. Fut.Perf. ☼ 14:00, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

I agree that would have been a bit disproportionate but the way the section is presented right now, giving only some Portuguese examples, can also be seen as a bit disproportionate, since all languages from the Iberian Peninsula have been linguistically influenced.

As I mentioned on my first message, I also didn’t know if a random website would be good enough as a source. I just thought it was worth adding since the sources on that article seemed quite legit.

About the Rasico paper, I originally mentioned it slightly for that reason, saying that the apocope could be attributed to Gothic influence. But yeah, I fully agree with you there.

Do you think it is a good idea still to add some vocabulary to the section? As I asked previously, would it be possible to add some Spanish vocabulary and and a link to the Gothic section of the ‘Influences on the Spanish language’ page? That would make the section about influences of the Gothic languages richer in content and more informative, in my opinion. Isarn Falb (talk) 14:25, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- There's a useful-looking list of loans across the whole of Romance in DENISSE ČEVELOVÁ – VÁCLAV BLAŽEKGOTHIC LOANS IN ROMANCE LANGUAGES. I've checked Gamillschegg and that seems to concentrate on loans into Italian. For the morphological aspect, I don't see the point in going into a lot of language-specific detail here, but I would guess there must be some cross-linguistic commonalities, though I can't claim any expertise in Romance linguistics. --Pfold (talk) 13:01, 5 July 2021 (UTC)

Audio

What a shame the audio has been removed. An article of this nature really is crying out for audio examples 2A00:23C8:1900:8A01:2995:CFD0:B269:47BB (talk) 07:15, 28 July 2022 (UTC)