Talk:Foundation of Moldavia/Sandbox

This sandbox now contains the original state of the article, before it was heavily reworked. Please feel welcome to "mine" it for otherwise unused material. __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The foundation of Moldavia – traditionally known as descălecat ("dismounting") in Romanian – is linked by the earliest Moldavian chronicles with a legendary hunt, which ended with the movement of the Vlach (Romanian) leader Dragoș and his people from Maramureș to the region of the Moldova River in the 1350s. Moldavia developed in the lands between the Carpathian Mountains and the Dniester River, which had been dominated by nomadic Turkic peoples – the Pechenegs, Ouzes and Cumans – from around 900. During the same period, the number of archaeological sites decreased: there are about 300 sites from the 9th and 10th centuries, but only about 35 sites dated to the 12th and 13th centuries. The neighboring Principality of Halych and Kingdom of Hungary started to expand their authority over parts of the territory from around 1150, but the Golden Horde took control of the lands east of the Carpathians in the 1240s. The Mongols promoted international commerce, and an important trade road developed along the Dniester. The circulation of Hungarian and Bohemian coins shows that there were also close economic contacts between the basin of the Moldova and Central Europe in the early 14th century.

In addition to the dominant Turkic population, medieval chronicles and documents mentioned other peoples who lived between the Carpathians and the Dniester, including the Ulichians and the Tivercians in the 9th century, and the Brodniki and the Alans in the 13th century. According to a scholarly theory, the Blökumenn or Blakumen, mentioned in Scandinavian sources written in the 11th and 13th centuries, were actually Vlachs who lived in the same territory. The Vlachs' presence in that territory is well-documented from the 1160s. Their local polities were first mentioned in the 13th century: the Mongols defeated the Qara-Ulagh, or Black Vlachs, in 1241, and the Vlachs invaded Halych in the late 1270s. The Vlachs came to Maramureș during the reign of one "King Vladislaus of Hungary" to fight against the Mongols, according to the Moldo-Russian Chronicle.

Both Poland and Hungary took advantage of the decline of the Golden Horde and started a new expansion in the 1340s. After a Hungarian army defeated the Mongols in 1345, new forts were built east of the Carpathians. Royal charters, chronicles and place names show that Hungarian and Saxon colonists settled in the region. Dragoș took possession of the lands along the Moldova with the approval of Louis I of Hungary, but the Vlachs rebelled against Louis I's rule already in the late 1350s. Dragoș was succeeded by his son, Sas, but Sas's son was expelled from Moldavia by a former voivode of Maramureș, Bogdan, in the early 1360s. Bogdan, who resisted Louis I's attempts to restore Hungarian suzerainty for several years, was the first independent ruler of Moldavia. The earliest Moldavian silver and bronze coins were minted in 1377. The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople acknowledged the Metropolitan See of Moldavia, after years of negotiations, in 1401.

Background

[edit]Moldavia emerged in the lands between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River in the 14th century.[1] During the previous millennium, the territory had been exposed to invasions by nomadic peoples.[2] A peaceful period followed the emergence of the Khazar Khaganate around 750, contributing to the growth of the population.[3] A new material culture – the "Dridu culture" – spread in the lands along the Lower Danube (in both present-day Bulgaria and Romania) and in the territory east of the Carpathians.[4] After the arrival of the Magyars to the Pontic steppes north of the Black Sea in the 830s, the local inhabitants fortified their settlements with palisades and deep moats along the Dniester in the 9th century.[5][6] The "Ulichians and the Tivercians lived by the Dniester, and extended as far as the Danube",[7] according to the Laurentian version of the Russian Primary Chronicle.[8][9] Al-Muqaddasi, a 10th-century Arab historian, listed the "Waladj" among the neighbors of the Turkic peoples.[10] An other 10th-century Muslim scholar, Ibn al-Nadim, mentioned a people named "Blaghā".[8] According to a scholarly theory, both ethnonyms may refer to the Vlachs, or Romanians, of the region of the Carpathians.[8]

The Magyars left the Pontic steppes for the Carpathian Basin after a coalition of the Pechenegs and the Bulgarians defeated them at the end of the 9th century.[11][12] The Pechenegs took control of the territory, but most "Dridu" settlements survived their arrival.[13] Only the fortifications were destroyed in the 10th or early 11th centuries.[14] New settlements appeared along the lower course of the Prut.[14] The local inhabitants' burial rites radically changed: inhumation replaced cremation and no grave goods can be detected after around 1000.[14]

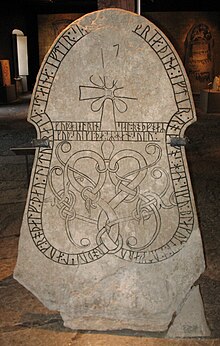

During the civil war which followed the death of Vladimir the Great, Grand Prince of Kiev, in the 1010s, one of Vladimir's sons, "Burizleif", sought refugee in "Tyrkland", but returned at the head of an army of "Tyrkir", "Blökumenn" and "a good many of other nasty people",[15] according to the Eymundar saga.[16] Historians who identify "Burizleif" with Sviatopolk I of Kiev associate the saga's "Tyrkir" with the Pechenegs (because Pechenegs supported Sviatopolk, according to the Russian Primary Chronicle), and the "Blökumenn" with the Vlachs.[17][18] A mid-11th-century runestone from Gotland in Sweden recorded the murder of a Varangian merchant, Rodfos, by "Blakumen" during a journey.[17] Many scholars identify the Blakumen as Vlachs from the lands between the Carpathians and the Black Sea. The "usual route of the Varangians from the Baltic coasts to Constantinople passed along the Moldavian littoral of the Black Sea".[19]

Under pressure by the nomadic Ouzes from the east, the Pechenegs made frequent raids against the Byzantine Empire in the 1040s.[20] The Ouzes were attacked from the east by the Cumans who had conquested the Bulaq and other Turkic peoples, according to the 11th-century Mahmud al-Kashgari.[21][22] The Pechenegs' mass migration to the Balkan Peninsula commenced in the late 1040s and the majority of the Ouzes followed them in the 1060s.[23] Those who stayed behind entered into the service of Rus’ princes or were integrated into other Turkic confederations.[24][25] The Cumans dominated the steppes between the Lower Danube and the Aral Sea from around 1070.[26][27] According to a 17th-century version of the Oghuzname, the Cumans' legendary hero, Qipchaq, fought against many peoples, including the "Ulâq" whom Florin Curta, Victor Spinei and other historians identify as Vlachs.[28][27]

Most settlements along the Lower Prut disappeared; new villages developed and a new archaeological culture – the "Răducăneni culture" – emerged in the woodlands along the middle course of the river between about 1050 and 1080.[29] The number of archaeological sites between the Carpathians and the Prut sharply diminished: about 100 sites can be dated to the 11th and 12th centuries in contrast with the nearly 300 sites from the previous two centuries.[30] Strongholds were built on the upper courses of the Dniester and the Prut, forming a defensive line along the frontiers of the Principality of Halych, or Galicia.[31] Ivan Rostislavich, a claimant to Halych, "did harm to Galician fishermen" on the Danube in 1159, according to the Hypatian version of the Russian Primary Chronicle, suggesting that the authority of Yaroslav Osmomysl, Prince of Halych, expanded as far as the Lower Danube.[32] The Lay of Igor's Campaign expressly stated that Yaroslav Osmomysl's "law reign[ed] up to the river Danube".[33][34] Historian Spinei says that the very fact that Ivan Rostislavich sought refuge in the lands along the Danube proves that the princes of Halych did not control the same region.[35]

Andronikos Komnenos, a rebellious cousin of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, fled from the Byzantine Empire in 1164.[36] Soon after reaching the borders of Halych, he was "[a]pprehended by the Vlachs, who had heard rumors of his escape",[37] according to the nearly contemporaneous Niketas Choniates.[36] This report is one of the references to the Vlachs' presence north of the Lower Danube.[38][36] Emperor Manuel dispatched two armies against the Kingdom of Hungary in 1166.[32] The contemporary historian John Kinnamos mentioned that the army, which invaded Hungary from the northeast, "had passed through some wearisome and rugged regions and had gone through a land entirely bereft of men".[39][40] The second army, which was under the command of John Komnenos Vatatzes, included "a large group of Vlachs".[41][36] The latter, however, were most probably recruited from the Vlach populations in the Byzantine Empire, according to historian Florin Curta.[32] Both Anna Komnene and Niketas Choniates testify that the Balkan Vlachs occasionally cooperated with the Cumans against the Byzantines.[42][43] Anna Komnena wrote of Vlachs who showed "the way through the passes"[44] of the Balkan Mountains to the Cumans who invaded the Byzantine Empire in 1095.[45][43][46] Choniates emphasized that the Cumans assisted the Vlachs and Bulgarians who rebelled against Byzantine authority in the northern Balkans in the late 12th century.[47]

Andrew II of Hungary granted Burzenland to the Teutonic Knights in 1211.[48] A 1222 charter, which may have been forged about a decade later, narrated that the Knights had expanded their authority over the Carpathians, taking control of the lands as far as the Lower Danube and the "borders of the Brodniks".[49][50] According to Spinei, the Brodniks were a small nomadic Turkic groups, closely related to the Cumans.[51] They betrayed their allies in the Battle of Kalka where the Mongols annihilated the united Rus' and Cuman forces in 1223.[52][53] The Cumans' power quickly declined after the battle.[54] The Teutonic Knights attempted to put their domains under the protection of the Holy See, but Andrew II of Hungary expelled them in 1225.[54]

A Cuman chieftain, Boricius and his retainers were baptized at a meeting with Robert, Archbishop of Esztergom, in 1227.[55] In the next year, a new Roman Catholic bishopric, the Diocese of Cumania, was established, which included the lands between the Carpathians and the Siret.[55] In a letter of 1234, Pope Gregory IX wrote of "a certain people within the Cuman bishopric named Walati", or Vlachs, who received "all the sacraments … from pseudo-bishops of the Greek rite", also tempting the Hungarians, "Teutons" and other Catholics who had came from Hungary into accepting the jurisdiction of their bishops.[56][57][58] The Galician–Volhynian Chronicle mentioned a series of wars that Daniel Romanovych, Prince of Halych, waged against the "princes of Bolokhoveni" between 1231 and 1257.[59] Some modern historians (for instance, Alexandru V. Boldur) identify the Bolokhoveni as Vlachs because of the similarity of the two ethnonyms; other scholars (including Victor Spinei) reject that identification.[59][60]

The Mongol army invaded the Cuman steppes in 1236, forcing large groups of the Cumans to seek refuge in Bulgaria, Hungary and other neighboring countries.[61][62] The Cumans who stayed behind were subjected to the Mongols.[63] The conquerors adopted the Cuman language during the next century.[64] The Mongols invaded the Kingdom of Hungary under the command of Batu Khan in March 1241.[65] The Mongols devastated the kingdom for a year, slaughtering thousands of peoples, but they withdrew without annexing Hungary.[66][67] Batu Khan established his capital at Sarai on the Volga; his new empire – known as the Golden Horde – included the Pontic steppes.[68] Historian Curta describes the Mongol invasion of 1241 and 1242 as a "major watershed in the medieval history of Southeastern Europe".[69] Hundreds of towns and villages were destroyed and the traditional trade route from Kiev to Central Europe was destructed.[70] There are no more than 35 archaeological sites between the Carpathians and the Prut that can be dated to the 12th and 13th centuries.[30] The establishment of Mongol authority stopped the eastward expansion of the Kingdom of Hungary.[71]

Incipient states

[edit]The ethnic composition of the population of the land where Moldavia would emerge is unclear.[72] According to a letter of Béla IV of Hungary, Ruthenes, Cumans and Brodniks inhabited the territory along the eastern borders of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1250.[53] Although 14th-century Italian maps refer to the Prut as Alanus fluvius, suggesting that Alans, or Yasi, had also settled in the region, the maps may have been copied from 7th-century charts, according to Spinei.[73][74] A village which was located near present-day Rezina bore the name Mordvina in 1437, implying that Mordvins had also arrived in the 14th century.[75] The Romanian names of hundreds of settlements and rivers between the Carpathians and the Dniester are of Turkic – either Pecheneg or Cuman – origin.[76] According to historian Spinei, who says that the Romanians formed the native population of the same region, some of the rivers may have once had a Romanian name; others may have been simply named as pârâu ("creek"), gârlă ("brook") or râu ("river"), because the distinction of those smaller bodies of water was less important for the local inhabitants than for the nomadic Turkic peoples.[77]

Chronicles, itineraries and other documents written in the late 13th or early 14th century refer to Vlachs who (possibly or probably) lived between the Carpathians and the Dniester.[78] According to the Persian historian, Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, a Mongol army "proceeded by way of the Qara-Ulagh, crossing the mountains … and defeating the Ulagh peoples"[79] during the Mongol invasion of 1241.[80][81] His narrative shows that the Quara-Ulagh, or Black Vlachs, lived in the Eastern or Southern Carpathians.[80][81] Giovanni di Plano Carpini, a papal envoy to the Great Khan of the Mongols, met one "Duke Olaha" who "was leaving with"[82] his retinue to the Mongols in 1247.[83] Victor Spinei, Vlad Georgescu and other historians identify the duke as a Vlach ruler, because his name is similar to the Hungarian word for Vlach ("oláh"),[84][83] but the name may have also been a version of Oleg.[85] Friar William of Rubruck, who visited the court of the Great Khan in the 1250s, listed "the Blac",[86] or Vlachs, among the peoples who paid tribute to the Mongols, but the Vlachs' territory cannot be determined.[85][83] Rubruck described "Blakia" as "Assan's territory"[87] south of the Lower Danube, showing that he identified it with the northern regions of the second Bulgarian Empire.[88]

According to Thomas Tuscus's chronicle, Ottakar II of Bohemia sought assistance from the "Ruthenes" against Rudolf I of Germany in 1276 or 1277, but the Ruthenes could not help him, because of their conflict with the Blaci, or Vlachs.[85][83] Tuscus's report shows that a Vlach polity existed in the region of Halych which was strong enough to wage war against that principality.[85] Pope Nicholas IV issued a bull for the Dominicans in 1288, authorizing them to preach among many peoples, including the Valachi, or Vlachs, who lived in the lands both to the south and to the north of the Lower Danube.[83][89]

According to the rhymed chronicle of Ottokar of Styria, Ladislaus Kán, Voivode of Transylvania who captured Otto the Bavarian, a claimant to Hungary, sent his prisoner to a Vlach herzog, or duke, whose lands were located "beyond the woods" – in northern Moldavia or in southern Transylvania – in 1307.[90][91] After Otto was released, Yuri I Lvovich, King of Halych, waged a war against the Wallahen Land ("the land of the Vlachs") and its duke.[91] Władysław I of Poland invaded Brandenburg at the head of a "Polish force, reinforced with contingents of Ruthenians, [Vlachs] and Lithuanians"[92] in 1326, according to the chronicle of Jan Długosz.[93][94] Papal letters of 1332 and 1337 mentioned that "the powerful of those parts" had seized the property of the former Diocese of Cumania.[93] Historian Tudor Sălăgean identifies them as Vlach landowners,[93] but the same designation may also refer to Catholic Transylvanian prelates and noblemen, according to Victor Spinei.[95]

No fortified settlements existed between around 1240 and 1350.[93] Centers of local administration developed near the Dniester in Costești and Orheiul Vechi.[93] Archaeological finds – kilns to produce pottery and furnaces to puddle iron ore – show that both towns were important economic centers of the Golden Horde.[96] At Orheiul Vechi, the ruins of a mosque and a bath were also excavated.[97] The local inhabitants used high quality ceramics (amphorae-like vessels, pitchers, mugs, jars and pots), similar to those found in other parts of the Golden Horde.[98] The Mongols supported international commerce, which led to the formation of a "Mongol road" from Kraków along the Dniester.[99] Almost 5000 Mongol coins from the first half of the 14th century have been excavated in the same region.[100][101] At the mouth of the Dniester, Cetatea Albă (now Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi in Ukraine) developed into an important emporium.[102] It was established by Genoese merchants in the late 13th century.[102]

Weapons and harness pieces from the 13th and 14th centuries that have been found together with agricultural tools at Vatra Moldoviței, Coșna and Cozănești shows the existence of either local elites or armed peasant groups between the Carpathians and the upper courses of the Siret.[93][103] Hungarian and Bohemian coins were in circulation in the same territory during the first half of the 14th century.[101] The local inhabitants used pottery of lower quality than those used in the lands directly controlled by the Mongols.[98]

Hungarian and Polish expansion

[edit]

Pope John XXII made the Franciscan friar, Vitus de Monteferreo, Bishop of Milkovia in 1334 in an attempt to reorganize tha Diocese of Cumania.[104] However, no document proves that he ever visited his see on the Milcov River.[104] Franciscan missionaries were also active in the region, if the reference to the martyrdom of two Franciscan friars in Siret in 1340 in the Annales minorum is reliable.[105][106]

Close commercial contacts with Transylvania contributed to the arrival of Saxon settlers.[101] Saxon potters established Baia, according to Grigore Ureche's chronicle.[107] Place names (including Sasca and Săseni) also evidence the one-time presence of Saxons in Moldavia.[108] A 1334 treaty between Halych and the Teutonic Knights mentioned one Alexandro Moldaowich.[109] For Baia was also known as the târg, or town, of Moldavia, Alexandro's byname may have been the earliest reference to the town, but it may have been also connected to a Polish settlement, Młoda.[109][110] The name of Baia derrived from the Hungarian word for mine (bánya).[108] Further place names and hydronyms of Hungarian origin, such as Bacău, Cuejd, which were first recorded in the 15th century, prove that Hungarians also settled in the territory.[111]

The disintegration of the Golden Horde started after the death of Öz Beg Khan in 1341.[112][113] Both Poland and Hungary started to expand towards the steppe zone in the 1340s.[114] Casimir III of Poland invaded the Principality of Halych already in 1340.[115] Two 14th-century chronicles – written by John of Küküllő and by an anomymous Minorite friar – Louis I of Hungary dispatched Andrew Lackfi, Count of the Székelys, to lead an army of Székely warriors against the Mongols who had made raids in Transylvania.[116][117] Lackfi and his army inflicted a crushing defeat upon a large Mongol army on 2 February 1345.[116][117] The Székelys again invaded the "land of the Tatars" in 1346.[116] According to both chronicles, the Mongols withdrew as far as the Dniester after their defeats.[116][117] Historian István Vásáry says that it "seems plausible" that the Vlachs of Maramureş took part in the campaigns against the Golden Horde, even if contemporaneous sources did not refer to them.[118] Archaeological research shows that forts were erected at Baia, Siret, Piatra Neamț and Târgu Trotuș in the late 1340s.[119] Pope Clement VI ordered the restoration of the Bishopric[clarification needed] of Milkovia on 29 January 1347.[118]

"Dismounting" by Dragoș

[edit]

The foundation of Moldavia is often mentioned as descălecat, or "dismounting", in Romanian historiography, because the oldest Moldavian chronicles linked the establishment of the principality to a hunting, which led Dragoș, the Vlach ruler who established Moldavia, and his people from Maramureş in the Kingdom of Hungary to the basin of the Moldova River.[120][118][121] According to a scholarly theory, which was first proposed by Nicolae Iorga, the Land of Maramureş was one of the "Romanias" where Eastern Romance ethnic groups (known as Vlachs in the Middle Ages) had survived the Great Migrations.[122] A concurring theory says that the Vlachs of Maramureş came from Great Vlachia (in present-day Macedonia) in the second half of the 13th century.[118]

The earliest contemporaneous reference to Romanians in Maramureş was recorded in a royal charter in 1326.[123] In that year, Charles I of Hungary granted the "land Zurduky" (now Strâmtura in Romania) in the "district of Maramureş" to a Vlach noble knez, Stanislau.[124] According to the so-called Moldo-Russian Chronicle, which was preserved in a Russian annals completed in 1505, one "King Vladislav of Hungary" invited the Romanians' ancestors to Maramureş to fight against the Mongols.[125][126] After defeating the Mongols with the Vlachs' help, the king settled them in Maramureş.[126][127] Historian Pavel Parasca identifies "King Vladislaus" with Ladislaus IV of Hungary who reigned between 1270 and 1290.[128]

The Moldo-Russian Chronicle writes that Dragoș was one of the Romanians whom "King Vladislav" had granted estates in Maramureş.[127][125] According to the various versions of the legend of his "dismounting", Dragoș left for a hunting, together with his retainers.[127][125] While chasing an aurochs or bison, they reached as far as the Moldova River where they killed the beast.[127][122][129] They liked the place where they stopped and decided to settle on the banks of the river.[127][122] Dragoș went back to Maramureș only to return with all his people "on the fringes of the lands where the Tatars roamed".[127][122] Ritual huntings which end with the establishment of a state, a town or a people are popular elements of the folklore of various peoples of Eurasia, including the Hungarians and the Lithuanians.[130] According to the Romanian scholar, Mircea Eliade, the story of Dragoș's "dismounting" is an authochtonous legend which had its origins in the Oriental and Mediterranean world.[130]

In the time of King Vladislav, the Tatars led by their prince, Neymet advanced from the waters of the Prut and the Moldova against the Hungarians. … King Vladislav … sent envoys to the Old-Romans and the Romanians. Thereupon we, Romanians joined forces with the Old-Romans and came to Hungary to help King Vladislav. … Before long, the decisive battle was fought between the Hungarian king, Vladislav, and the Tatar prince, Neymet, along the banks of the Tisa. The Old-Romans started the fight, preceding everybody else. They were followed by the masses of the Hungarians and the Romans who were in the Latin faith. Thus the Tatars were defeated first by the Old-Romans, then by the Hungarians and the Romanians. … Vladislav, the Hungarian king rejoiced over the divine assistance. He highly appreciated and rewarded the Old-Romans for their courage. … [T]hey asked King Vladislav not to force them to adopt the Latin faith, but to let them keep their own Christian faith according to the Greek rite and to grant them a place to stay. King Vladislav … granted them lands in Maramureș between the Mureș and Tisa at a place called Crij. The Old-Romans gathered and settled there. They married Hungarian women and led them into their own Christian religion. … There was a smart and courageous man, Dragoș, among them. One day, he left with his companions for a hunt and they came across the footprints of a bison. Following it, they crossed the snowy mountains and arrived at a wonderful and even place where they spotted the bison. They killed it under a willow and feasted on it. Then God brought the idea to his mind that he should find a new homeland and settle there. … [T]hey returned home and spoke of the beauty of that country and of its rivers and springs to the other people so that to convince them to move there. The latter also liked the idea and decided to leave for the place where their companions were staying and to search for a new homeland. It was surrounded by deserted lands and the Tatars and their cattle roamed in the borderlands. Thereupon they asked Vladislav, the Hungarian king, to let them leave, and King Vladislav graciously assented. They left Maramureș, together with all their companions and with their wives and children, to cross the high mountains. Many trees were cut down and many cliffs were pushed aside, but they crossed the mountains and arrived at the place where Dragoș had killed the bison. They liked it and dismounted there. They chose an intelligent man named Dragoș of their number and appointed him to be their lord and voivode, and thus the country of Moldavia was founded by the will of God.

The "dismounting" by Dragoș took place in 1359, according to most Moldavian chronicles.[133] The only exception is the Moldo-Polish chronicle which says that the "dismounting" occurred in 1352.[133] However, the same chronicles add various years when determining the period between Dragoș's arrival to Moldavia and the first year of the reign of Alexander the Good in 1400.[133] For instance, the Anonymous Chronicle of Moldavia mentioned 44 years, but the Moldo-Russian Chronicle wrote of 48 years.[133] Consequently, the date of the dismounting is debated by modern historians.[133] For instance, Dennis Deletant says that Dragoș came to Moldavia soon after the establishment of the Diocese of Milkovia in 1347.[134]

Moldavia emerged as a "defensive border province" of the Kingdom of Hungary.[135] A version of Grigore Ureche's chronicle stated that Dragoș's rule in Moldavia "was like a captaincy", implying that he was a military commander.[136] Louis I of Hungary mentioned Moldavia as "our Moldavian land".[118] The province initially included the northwestern part of the future principality (it is now known as Bukovina).[137] In 1360, King Louis granted estates to a Vlach lord, Dragoș of Giulești, for subjecting the Vlachs who had revolted against Louis I in Moldavia.[138] The identification of Dragoș of Giulești with the first ruler of Moldavia is subject to scholarly debates.[138][139]

In addition to Dragoș's province, other polities also existed between the Carpathians and the Dniester.[139] A fort was erected at Orheiul Vechi and the local Mongol ruler minted his own copper coins after around 1350, which had been found between the Dniester and Prut.[140][141] Two 15th-century historians – Jan Długosz and Filippo Buonaccorsi – wrote of a Polish campaign against one Voivode Peter in Moldavia in 1359.[139][142] According to Długosz's narrative, Peter expelled his brother, Stephen, after the death of their father, because most local Vlachs and Hungarians supported him.[143] Stephen sought assistance from Casimir III of Poland, promising him to accept his suzerainty.[144] Casimir III sent Polish and Ruthenian troops to Moldavia in June, but Voivode Peter defeated them at Şipeniţ (now Shypyntsi in Ukraine).[144] Whether the Polish expedition actually took place during the reign of Casimir III, or Długosz and Buonaccorsi misdated a Polish campaign that was launched against Moldavia after the death of Lațcu of Moldavia in 1375, is subject to scholarly debates.[145][146]

Stephen, Voivode of Moldavia, has died while among the [Vlachs], whose ancestors had been expelled from Italy; it is said they were the Volsci, and who, having cunningly squeezed out the former Ruthenian lords and settlers, as their numbers increased, adopted their faith and customs, thus making it easier for themm to assume control. The voivode's death marks the start of a fierce struggle for the ducal throne between Stephen's two sons, Stephen and Peter. The younger of the two, Peter, has the support of the majority of the [Vlachs], … and he also enjoys the support of the many Hungarians living in the country; so, having chased out his brothers and those boyars [whom] he has been unable to win over, he assumes control of Moldavia. His elder brother … escapes to the King of Poland, who has wealth and soldiers in plenty, … promising that … he … and his successors, his voivodes and boyars will for ever be loyal, obedient subjects of King Casimir and his successors. The King's advisers recommend acceptance, so he givers Stephen an army of knights from Cracow, Sandomierz, Lublin and Ruthenia, with which to recover his duchy. The army … enjoys success in a number of engagements and in some individual encounters, but it never comes to a pitched battle, for Peter realizes that that would be too dangerous.

— Jan Długosz: Annals or Chronicles of the Famous Kingdom of Poland[147]

Bogdan the Founder

[edit]The earliest Moldavian chronicles, which began their lists of the rulers of Moldavia with Dragoș, stated that Dragoș was succeeded by his son, Sas, who reigned for four years.[148] The only exception is the list of the voivodes which was recorded in the Bistrița Monastery in 1407, because it did not mention Dragoș and Sas, but started with "Bogdan Voivode".[149] Bogdan who had been the voivode of the Vlachs in Maramureș gathered the Vlachs in that district and "secretly passed into Moldavia", according to John of Küküllő's chronicle.[150][151] Royal charters recorded that Bogdan had come into a conflict with János Kölcsei, the royal castellan of Visk (now Vyshkovo in Ukraine), in 1343, and with a Vlach lord in Maramureș, Giula of Giulești, in 1349.[152] According to historian Radu Carciumaru, Bogdan's conflict with the royal castellan shows that he had been opposed to the presence of the representatives of royal authority in Maramureș years before he left for Moldavia.[152]

The dating of Bogdan's departure is uncertain.[153] His estates in Maramureș were confiscated and granted to the son of Sas, Balc, according to a royal diploma, issued on 2 February 1365.[151][154] Consequently, Bogdan must have come to Moldavia before that date.[155] Historian Pál Engel writes that Bogdan arrived in 1359, taking advantage of the anarchy that followed the death of Berdi Beg, Khan of the Golden Horde.[156] According to Carciumaru, a lasting conflict between Louis I of Hungary and Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and the Lithuanians' victory over the Tatars in the Battle of Blue Waters in the early 1360s, enabled Bogdan to come to Moldavia and expel Balc in 1363.[157] Sălăgean says that it was only in 1365 that Bogdan seized power in Moldavia with the assistance of local Vlachs.[4]

Louis I of Hungary attempted to restore his rule in Moldavia, but the chronology of the military actions against Bogdan is uncertain.[156][158] John of Küküllő wrote that Bogdan "was often battled against" by the army of Louis I of Hungary, but the "number of Vlachs inhabiting that land increased, transforming it into a country".[159][160] Although Küküllő stated that Bogdan was finally forced to accept Louis I's suzerainty and to pay a yearly tribute to him, modern historians – including Denis Deletant, Tudor Sălăgean, Victor Spinei, and István Vásáry – agree that Bogdan could actually preserve the independence of Moldavia.[151][158][4][161]

Aftermath

[edit]

The new state received its name after the river Moldova.[162] In Latin and Slavic documents, it was mentioned as "Moldova", "Moldava" or "Moldavia".[162] On the other hand, the Byzantines, who regarded it as a new Vlachia, referred to the country as Maurovlachia ("Black Vlachia"), Rusovlachia ("Vlachia near Russia") or Moldovlachia ("Moldavian Vlachia").[162] The Turkish name of Moldavia – Kara Boğdan – demonstrates Bogdan's preeminent role in the establishment of the principality.[163]

Moldavia initially included a small territory between the Prut and Siret.[114] The minting of Mongol coins continued in Orheiul Vechi until 1367 or 1368, showing that a "late Tatar state" survived in the southern region between the Prut and the Dniester.[164][160] Louis I of Hungary exempted the merchants of "Demetrius, Prince of the Tatars" from paying taxes in Hungary in exchange for securing the tax exempt status of the merchants of Brașov in "the country of Lord Demetrius".[160]

Bogdan was succeeded by his son, Lațcu, around 1367.[160] No Mongol coins minted after 1368 or 1369 have been found in the region of the Dniester, showing that the Mongol rulers did not control the territory any more.[165] After Franciscan friars from Poland converted him to Catholicism, Lațcu initiated the establishment of a Roman Catholic diocese in Moldavia in 1370.[166][167] His direct correspondence with the Holy See shows that he wanted to demonstrate the independence of Moldavia.[167] Upon Lațcu's request, Pope Gregory XI set up the Roman Catholic Diocese of Siret in 1371, addressing his bull to "Lațcu, Duke of Moldavia".[160][168] According to Sălăgean, the Holy See "consolidated the international status of Moldavia" by granting the title "duke" to Lațcu.[160] On 14 March 1372, Louis I of Hungary, who had also inherited Poland in 1370, signed a treaty with Emperor Charles IV who acknowledged Louis I's rights in many lands, including Moldavia.[169]

Lațcu, who died in 1375, was succeeded by Peter I Mușat, according to the earliest lists of the rulers of Moldavia.[170] However, the 15th-century Lithuanian-Ruthenian Chronicle wrote that the Vlachs elected George Koriatovich – who was a nephew of Algirdas, Grand Prince of Lithuania, and ruled in Podolia under Polish suzerainty[171] – voivode, but later poisoned him.[172][173] In late 1377, Vladislaus II of Opole, who administered Halych in the name of Louis I of Hungary, gave shelter to one "Vlach voivode", named George, who had fled to Halych because of the "unexpected treason of his people".[172][171] According to Spinei, George Koriatovich died in 1375, which excluds his identification with "Voivode George".[172] Spinei also says that George Koriatovich most probably ruled in southeastern Moldavia which had been liberated from Mongol rule.[172] The first Moldavian silver and bronze coins were minted for Peter I Mușat in 1377.[174]

According to a record in the register of the Genoese colony in Caffa on the Black See, two Genoese envoys were sent to "Constantino et Petro vayvoda" in 1386.[175][176] Historians identified Voivode Constantino with Costea, whom the list of the voivodes of Moldavia, recorded in the Bistrița Monastery, mentioned between Lațcu and Peter.[176] The record in the Caffa register suggests that the two voivodes – Costea and Peter I Mușat – had the same position.[176] The division of the medieval principality into two greater administrative units – Ţara de Sus ("Upper Country") and Ţara de Jos ("Lower Country") – , each administered by a high official, the vornic, also implies the former existence of two polities which were united by the Moldavian monarchs.[177][178]

Peter I Mușat paid homage to Władysław II Jagiełło, King of Poland, in Kraków on 26 September 1387.[158] Upon Peter's request, Anton, the Orthodox Metropolitan of Halych, ordained two bishops for Moldova, one of them being Joseph Mușat, who was related to the voivode.[179] However, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople refused to acknowledge their consecration.[179] Peter I Mușat expanded his authority as far as the Danube and the Black Sea.[180] His successor, Roman I Mușat, styled himself "By the grace of God the Almighty, Voivode of Moldavia and her to the entire Vlach country from the mountains to the shores of the sea" on 30 March 1392.[181][182] After years of negotiations, the Ecumenical Patriarch, Matthew I, acknowledged Joseph Mușat as Metropolitan of Maurovlachia in 1401.[179]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 135.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 7.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 48–50.

- ^ a b c Sălăgean 2005, p. 135.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 124, 157, 185.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 85.

- ^ The Russian Primary Chronicle (Prologue, 12), p. 56.

- ^ a b c Spinei 2009, p. 83.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 185.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 82.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 153.

- ^ Djuvara 2014, p. 52.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 94, 96.

- ^ a b c Curta 2006, p. 186.

- ^ Eymund's Saga (ch. 8.), p. 79.

- ^ Spinei 1986, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Spinei 1986, p. 56.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 303.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 55.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 107.

- ^ Golden 1984, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 108–109, 114.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 111, 114–115.

- ^ Martin 1993, p. 54.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 137.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 306.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 307.

- ^ a b Spinei 2009, p. 193.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 315–316.

- ^ a b c Curta 2006, p. 316.

- ^ The Tale of Igor's Campaign|The Lay of Igor's Campaign, p. 182.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 137.

- ^ a b c d Spinei 2009, p. 132.

- ^ O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniates (2.4.131) , p. 74.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 317.

- ^ Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus by John Kinnamos (6.3.261), p. 196.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 316–317.

- ^ Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus by John Kinnamos (6.3.260), p. 195.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b Vásáry 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Anna Comnena: The Alexiad (10.3.), p. 299.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 122.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 157.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 360–361.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 28.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 405.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 146, 159.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 159.

- ^ Martin 1993, pp. 146, 150.

- ^ a b Spinei 1986, p. 107.

- ^ a b Sălăgean 2005, p. 172.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 406.

- ^ Rădvan 2010, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Andreescu 1998, p. 84.

- ^ Spinei 1986, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b Spinei 2009, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Boldur 1992, p. 111-119.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Djuvara 2014, p. 58.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 409–410.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 410.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Martin 1993, p. 156.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 413.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 414.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 155.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 144.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 145.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 311, 318–321.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 322.

- ^ Spinei 1986, pp. 130–134.

- ^ The Successors of Genghis Khan (ch. 1.), p. 70.

- ^ a b Andreescu 1998, p. 78.

- ^ a b Spinei 1986, p. 113.

- ^ The Story of the Mongols Whom We Call the Tartars by Giovanni DiPlano Carpini (ch. 9.), p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e Spinei 1986, p. 131.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Sălăgean 2005, p. 196.

- ^ The Mission of Friar William of Rubruck (ch. 18.1.), p. 126.

- ^ The Mission of Friar William of Rubruck (ch. 1.5.), p. 126.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Dobre 2009, p. 36.

- ^ Andreescu 1998, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Rădvan 2010, p. 315.

- ^ The Annals of Jan Długosz (A.D. 1326), p. 273.

- ^ a b c d e f Sălăgean 2005, p. 197.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 133.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 162.

- ^ Spinei 1986, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Rădvan 2010, p. 521.

- ^ a b Spinei 1986, p. 150.

- ^ Rădvan 2010, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 152.

- ^ a b c Sălăgean 2005, p. 198.

- ^ a b Rădvan 2010, pp. 476–477.

- ^ Spinei 1986, pp. 162–163, 226.

- ^ a b Spinei 1986, p. 178.

- ^ Rădvan 2010, p. 316.

- ^ Dobre 2009, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Rădvan 2010, p. 353.

- ^ a b Spinei 1986, p. 140.

- ^ a b Rădvan 2010, p. 458.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 35.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 141.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 133.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 127.

- ^ a b Sedlar 1994, p. 24.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d Spinei 1986, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Vásáry 2005, p. 156.

- ^ a b c d e Vásáry 2005, p. 157.

- ^ Rădvan 2010, p. 334.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 88.

- ^ Carciumaru 2012, p. 172.

- ^ a b c d Andreescu 1998, p. 92.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 270.

- ^ Carciumaru 2012, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b c Spinei 1986, p. 197.

- ^ a b Vékony 2000, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f Brătianu 1980, p. 129.

- ^ Parasca 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Brezianu & Spânu 2007, p. 127.

- ^ a b Spinei 1986, p. 198.

- ^ Bogdan 1891, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Vékony 2000, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c d e Spinei 1986, p. 200.

- ^ Deletant 1986, p. 190.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Carciumaru 2012, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 203.

- ^ a b Spinei 1986, p. 201.

- ^ a b c Sălăgean 2005, p. 200.

- ^ Rădvan 2010, p. 346.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 154.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 196.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 194.

- ^ a b Knoll 1972, p. 240.

- ^ Knoll 1972, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Spinei 1986, pp. 194–195.

- ^ The Annals of Jan Długosz (A.D. 1359), pp. 308-309.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 195, 200.

- ^ Andreescu 1998, p. 94.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 206.

- ^ a b c Vásáry 2005, p. 159.

- ^ a b Carciumaru 2012, p. 182.

- ^ Carciumaru 2012, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 207.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 207–208.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 166.

- ^ Carciumaru 2012, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Deletant 1986, p. 191.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 207.

- ^ a b c d e f Sălăgean 2005, p. 201.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 211.

- ^ a b c Vásáry 2005, p. 143.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 160.

- ^ Rădvan 2010, p. 325.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 216.

- ^ Dobre 2009, p. 39.

- ^ a b Deletant 1986, p. 193.

- ^ Andreescu 1998, p. 95.

- ^ Deletant 1986, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Spinei 1986, pp. 195, 217.

- ^ a b Andreescu 1998, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d Spinei 1986, p. 217.

- ^ Deletant 1986, p. 198.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 27.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b c Spinei 1986, p. 218.

- ^ Spinei 1986, p. 220.

- ^ Brezianu & Spânu 2007, pp. 382–383.

- ^ a b c Papadakis & Meyendorff 1994, p. 264.

- ^ Treptow & Popa 1996, p. 136.

- ^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 202.

- ^ Brezianu & Spânu 2007, p. 303.

References

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- "Eymund's Saga". In Vikings in Russia: Yngvar's Saga and Eymund's Saga (Translated and Introduced by Hermann Palsson and Paul Edwards) (1989). Edingburgh University Press. pp. 69–89. ISBN 0-85224-623-4.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation b Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

- O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniatēs (Translated by Harry J. Magoulias) (1984). Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8.

- The Annals of Jan Długosz (An English abridgement by Maurice Michael, with commentary by Paul Smith) (1997). IM Publications. ISBN 1-901019-00-4.

- "The lay of Igor's campaign". In Medieval Russia's Epics, Chronicles, and Tales (Edited by Serbe A. Zenkovsky) (1963). Meridian. pp. 167–190. ISBN 978-0-452-01086-4.

- The Mission of Friar William of Rubruck (His journey to the cour to the Great Khan Möngke, 1253–1255 (Translated by Peter Jackson; Introduction, notes, and appendices by Peter Jackson with David Morgan) (2009). Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87220-981-7.

- The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text (Translated and edited by Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor) (1953). Medieval Academy of America. ISBN 978-0-915651-32-0.

- The Successors of Genghis Khan (Translated from the Persian of Rashīd Al-Dīn by John Andrew Boyle) (1971). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03351-6.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Andreescu, Stefan (1998). "The making of the Romanian principalities". In Giurescu, Dinu C.; Fischer-Galați, Stephen (eds.). Romania: A Historic Perspective. East European Monographs. pp. 77–104. OCLC 237138831.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bogdan, Ioan (1891). Vechile cronici moldovenești până la Ureche [Old Moldavian Chronicles before Ureche] (in Romanian). Editură Göbl.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boldur, Alexandru V. (1992). Istoria Basarabiei [History of Bessarabia] (in Romanian). Editura V. Frunza. ISBN 978-58-58-86027-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brătianu, Gheorghe I. (1980). Tradiția istorică despre întemeierea statelor românești [The Historical Tradition of the Foundation of the Romanian States] (in Romanian). Editura Eminescu.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brezianu, Andrei; Spânu, Vlad (2007). Historical Dictionary of Moldova. Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-5607-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carciumaru, Radu (2012). "The Genesis of the Medieval State on the Romanian Territory: Moldavia". Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana. 2 (12): 172–188.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Deletant, Dennis (1986). "Moldavia between Hungary and Poland, 1347–1412". The Slavonic and East European Review. 64 (2): 189–211.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Djuvara, Neagu (2014). A Brief Illustrated History of Romanians. Humanitas. ISBN 978-973-50-4334-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dobre, Claudia Florentina (2009). Mendicants in Moldavia: Mission in an Orthodox Land. Aurel Verlag und Handel Gmbh. ISBN 978-3-938759-12-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0511-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Golden, P. B. (1984). "Cumanica: The Qipčaqs in Georgia". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. IV. Harrassowitz Verlag: 45–87. ISBN 978-3-447-08527-4.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Knoll, Paul W. (1972). The Rise of the Polish Monarchy: Piast Poland in East Central Europe, 1320–1370. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-44826-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martin, Janet (1993). Medieval Russia, 980–1584. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67636-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Papadakis, Aristeides; Meyendorff, John (1994). The Christian East and the Rise of the Papacy: The Church, 1071–1453 AD. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-058-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Parasca, Pavel (2011). "Cine a fost "Laslău craiul unguresc" din tradiția medievală despre întemeierea Țării Moldovei [Who was "Laslău, Hungarian king" of the medieval tradition on the foundation of Moldavia]" (PDF). Revista de istorie și politică (in Romanian). IV (1). Universitatea Libera Internationala din Moldova: 7–21. ISSN 1857-4076. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rădvan, Laurenţiu (2010). At Europe's Borders: Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18010-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sălăgean, Tudor (2005). "Romanian Society in the Early Middle Ages (9th–14th Centuries AD)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 133–207. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97290-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spinei, Victor (1986). Moldavia in the 11th–14th Centuries. Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste Româna.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Treptow, Kurt W.; Popa, Marcel (1996). Historical Dictionary of Romania. Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-3179-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83756-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vékony, Gábor (2000). Dacians, Romans, Romanians. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-13-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

[edit]- Bolovan, Ioan; Constantiniu, Florin; Michelson, Paul E.; Pop, Ioan Aurel; Popa, Cristian; Popa, Marcel; Scurtu, Ioan; Treptow, Kurt W.; Vultur, Marcela; Watts, Larry L. (1997). A History of Romania. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-98091-0-3.

- Castellan, Georges (1989). A History of the Romanians. East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-154-2.

- Durandin, Catherine (1995). Historie des Roumains [History of the Romanians] (in French). Librairie Artheme Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-59425-5.

- Pop, Ioan Aurel (1999). Romanians and Romania: A Brief History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-88033-440-1.