Talk:Cognitive flexibility

| Cognitive flexibility has been listed as one of the Social sciences and society good articles under the good article criteria. If you can improve it further, please do so. If it no longer meets these criteria, you can reassess it. | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Current status: Good article | |||||||||||||

| This article is rated GA-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Lead

[edit]Cognitive flexibility has been described as the mental ability to switch between thinking about two different concepts, and to think about multiple concepts simultaneously. Despite some disagreement in the literature about how to operationally define the term, one commonality is that cognitive flexibility is a component of executive functioning. Research has primarily been conducted with children at the school age; however, individual differences in cognitive flexibility are apparent across the lifespan. Measures for cognitive flexibility include the A-not-B task, Dimensional Change Card Sorting Task, Multiple Classification Card Sorting Task, Wisconsin Card Sorting Task, and the Stroop Test. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) research has shown that specific brain regions are activated when a person engages in cognitive flexibility tasks. These regions include the prefrontal cortex (PFC), basal ganglia, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and posterior parietal cortex (PPC)[17]. Studies conducted with people of various ages and with particular deficits have further informed how cognitive flexibility develops and changes within the brain. Cognitive flexibility also has implications both inside and outside of the classroom. A person’s ability to switch between modes of thought and to simultaneously think about multiple concepts has been shown to be a vital component of learning.

Definitions

[edit]Cognitive flexibility can be seen from a variety of viewpoints. A synthesized research definition of cognitive flexibility is a switch in thinking, whether that is specifically based on a switch in rules or broadly based on a need to switch one’s previous beliefs or thoughts to new situations. Moreover, it refers to simultaneously considering multiple aspects of thought at once, whether they be two aspects of a specific object, or many aspects of a complex situation. Other terms for cognitive flexibility include mental flexibility, shifting, mental set or cognitive shifting, task switching/shifting, and attention switching/shifting.

Most commonly, cognitive flexibility refers to the mental ability to adjust thinking or attention in response to changing goals and/or environmental stimuli.[1] Researchers have more specifically described cognitive flexibility as the capacity to shift or switch one’s thinking and attention between different tasks or operations typically in response to a change in rules or demands.[2] For example, when sorting cards based on specific rules, children are considered cognitively flexible if they are able to successfully switch from sorting cards based on the color of the object to sorting based on the type of object on the card. Cognitive flexibility has been more broadly a described s the ability to adjust one’s thinking from old situations to new situations[3] as well as the ability to overcome responses or thinking that have become habitual and adapt to new situations.[4] Thus, if one is able to overcome previously held beliefs or habits (when it is required for new situations) then they would be considered cognitively flexible. Lastly, the ability to simultaneously consider two aspects of an object, idea, or situation at one point in time[5] refers to cognitive flexibility. According to this definition, when sorting cards based on specific rules, children are considered cognitively flexible rules if they can sort cards based on the color of the objects and type of objects on the card simultaneously. Similarly, cognitive flexibility has been defined as having the understanding and awareness of all possible options and alternatives simultaneously within any given situation.[6]

Contributing Factors

[edit]Regardless of the specificity of the definition, researchers have generally agreed that cognitive flexibility is a component of executive functioning, higher-order cognition involving the ability to control one’s thinking.[7] Executive functioning includes other aspects of cognition, including inhibition, memory, emotional stability, planning, and organization. Cognitive flexibility is highly related with a number of these abilities, including inhibition, planning and working memory.[2] Thus, when an individual is better able to suppress aspects of a stimulus to focus on more important aspects (i.e. inhibit color of object to focus on kind of object), they are also more cognitively flexible. In addition, they are better at being able to plan and organize as well as have better memory capabilities and strategies.

Researchers have also argued that cognitive flexibility is a component of multiple classification, as originally described by Piaget, whereby children must be able to classify objects in several different ways simultaneously so as to flexibly think about them.[8] Similarly, in order to be cognitively flexible they must overcome centration, which is the tendency for young children to solely focus on one aspect of an object/situation.[9] For example, when children are young they may be solely able to focus on one aspect of an object (i.e. color of object), and be unable to focus on both aspects (i.e. both color and kind of object). Thus, research suggests if an individual is centrated in their thinking, then they will be more cognitively inflexible.

Research has suggested that cognitive flexibility is related to other cognitive abilities, such as fluid intelligence,[10] reading fluency, and reading comprehension.[8] Fluid intelligence is described as the ability to solve problems in new situations; thus, when one is able to reason fluidly, then they are more likely to be cognitively flexible. In addition, those who are able to be cognitively flexible have been shown to have the ability to switch between and/or simultaneously think about sounds and meanings, which increases their reading fluency and comprehension. Cognitive flexibility has also been shown to be related to one’s ability to cope in particular situations. For example, when individuals are better able to shift their thinking from situation to situation they will focus less on stressors within these situations.[11]

In general, researchers in the field focus on development of cognitive flexibility between the ages of three and five. However, cognitive flexibility has been shown to be a broad concept that can be studied with all different ages and situations. Thus, with tasks ranging from simple to more complex, research suggests that there is a developmental continuum that spans from infancy to adulthood.

Measures/Assessments

[edit]Varying tests are appropriate for distinguishing between different levels of cognitive flexibility at different ages. Following are the common tests used to assess cognitive flexibility in the order of the applicable age.

A-not-B Task

[edit]In the A-not-B Task, children are shown an object hidden at Location A within their reach, and are then prompted to search for the object at Location A, where they find it. This activity is repeated several times, with the hidden object at Location A. Then, in the critical trial, the object is hidden in Location B, a second location within easy reach of child. Typically, children younger than one year search for the object under Location A, where the object had been previously hidden. However, after their first birthday, children are capable of switching to locate the object in Location B, demonstrating flexibility. Researchers have agreed that the A-not-B task is a easy task that measures cognitive flexibility during infancy.[12][13]

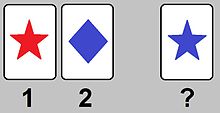

Dimensional Change Card Sorting Task (DCCS)

[edit]In the Dimensional Change Card Sorting Task, children are asked to sort cards by a single dimension (such as color) initially, and are subsequently required to alter their strategy to sort cards based on a second dimension (such as shape). Typically, research shows that 3-year-old children are able to sort cards based on a single dimension, but are unable to switch to sort the cards based on a second dimension. However, 5-year-old children are able to sort cards based on one dimension and can then switch to sorting cards on a second dimension.[13][14]

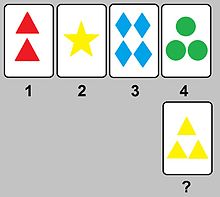

Multiple Classification Card Sorting Task

[edit]In the Multiple Classification Card Sorting Task, children are shown cards and asked to sort them based on two different dimensions (e.g. by color-yellow and blue, and kind of object-animals and foods) simultaneously into four piles within a matrix (e.g. yellow animals, yellow foods, blue animals and blue foods). This task appears to be more difficult as research has shown that 7-year-old children were incapable of sorting cards based on the two dimensions simultaneously. These children focused on the two dimensions separately, whereas 11-year-old children were capable of sorting cards based on these two dimensions simultaneously. This demonstrates an increase in cognitive flexibility between the ages of 7 and 11 years.[5][8]

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

[edit]The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) is used to determine an individual's competence in abstract reasoning, and the ability to change problem-solving strategies when needed.[15] In this test, a number of cards are presented to the participants. The figures on the cards differ with respect to color, quantity, and shape. The participants are then given a pile of additional cards and are asked to match each one to one of the previous cards. Typically, children between ages 9 and 11 are able to show the cognitive flexibility that is needed for this test.[13][16]

Stroop Test

[edit]The Stroop Test is also known as the Color-word Naming Test. In this paradigm, three cards populate the deck: the "color card" which displays patches of different colors, and the participants are asked to utter the names of the colored patches as rapidly as possible. The "word card" displays the names of colors printed in black and white ink, and the participants are asked read aloud the color names as rapidly as possible. The final card type is the "color-word card", which displays the names of the colors printed in an ink of a conflicting color (e.g. the word RED be printed in yellow), and participants are required to name the colors of the inks while ignoring the conflicting printed color names. The basic score on each card is the total time (in seconds) the participant takes to utter the required verbalization.[17] Typically, naming the color of the word takes longer and results in more errors when the color of the ink does not match the name of the color. At this situation, adults typically take longer to respond than children because adults are more sensitive to the meaning of a certain word of color and thus are more likely to be affected by it when naming the color of this word.

Neural Underpinnings

[edit]The mechanisms underlying cognitive flexibility have been explored extensively using various methods. Human studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have revealed a variety of distinct regions of the brain that work in concert from which flexibility could be predicted reliably, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), basal ganglia, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and posterior parietal cortex (PPC).[18]

The regions active during engagement of cognitive flexibility depend on the task and various factors involved in flexibility that are used to assess the behavior, as flexible thinking requires aspects of inhibition, attention, working memory, response selection, and goal maintenance.[2] Several studies using task switching paradigms have demonstrated the complexities of the network involved in cognitive flexibility. Activation of the dorsolateral PFC has been shown during resolution of interference of irrelevant task sets.[19] Another study further extended these results by demonstrating that the level of abstractness of the switch type influenced recruitment of differing regions in the PFC depending on whether the participant was asked to make a cognitive set switch, a response switch, or a stimulus or perceptual switch. A set switch would require switching between task rules, as with the WCST, and is considered to be the most abstract. A response switch would require different response mapping, such as circle right button and square left button and vice versa. Lastly, a stimulus or perceptual set switch would require a simple switch between a circle and a square. Activation is mediated by the level of abstractness of the set switch in an anterior to posterior fashion within the PFC, with the most anterior activations elicited by set switches and the most posterior activations resulting from stimulus or perceptual switches.[20] The basal ganglia is active during response selection[21] and the PPC, along with the inferior frontal junction are active during representation and updating of task sets called domain general switching.

Development of Cognitive Flexibility

[edit]Children can be strikingly inflexible when assessed using traditional tests of cognitive flexibility, but this does not come as a surprise considering the many cognitive processes involved in the mental flexibility, and the various developmental trajectories of such abilities. With age, children generally show increases in cognitive flexibility which is likely a product of the protracted development of the frontoparietal network evident in adults, with maturing synaptic connections, increased myelination and regional gray matter volume[22] occurring from birth to mid-twenties.

Deficits in Cognitive Flexibility

[edit]Diminished cognitive flexibility has been noted in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders such as Anorexia nervosa, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Schizophrenia, Autism, and in a subset of people with ADHD[23][24] . Each of these disorders exhibit varying aspects of cognitive inflexibility. For example, those with obsessive compulsive disorder experience difficulty shifting their attentional focus as well as inhibiting motor responses.[25] Children with autism show a slightly different profile with deficits in adjusting to changing task contingencies, while often maintaining the ability to respond in the face of competing responses.[26] Potential treatments may lie in neurochemical modulation. Juveniles with Anorexia nervosa have marked decreases in set-shifting abilities, possibly associated with incomplete maturation of prefrontal cortices associated with malnutrition.[27] One can also consider people with addictions to be limited in cognitive flexibility, in that they are unable to flexibly respond to stimuli previously associated with drug.[28]

Cognitive Flexibility and Aging

[edit]The elderly often experience deficits in cognitive flexibility. The aging brain undergoes physical and functional changes including a decline in processing speed, central sensory functioning, white matter integrity, and brain volume. Regions associated with cognitive flexibility such as the PFC and PC atrophy, or shrink, with age, but also show greater task-related activation in older individuals when compared to younger individuals.[29] This increase in blood flow is potentially related to the evidence that atrophy heightens blood flow and metabolism, which is measured as the BOLD response, or blood-oxygen-level dependence, with fMRI. Studies suggest that aerobic exercise and training can have plasticity inducing effects that could potentially serve as an intervention in old age that combat the decline in executive function.[30]

Implications for Education and General Learning

[edit]Educational Applications

[edit]Cognitive flexibility and other executive function skills are crucial to success both in classroom settings and life. A study examining the impact of cognitive intervention for at-risk children in preschool classrooms found that children who received such intervention for one to two years significantly outperformed their peers. Compared to same-age children who were randomly assigned to the control condition (a literacy unit developed by the school district), preschoolers who received intervention achieved accuracy scores of 85% on tests of inhibitory control (self-discipline), cognitive flexibility, and working memory.[31] Their peers in the control (no intervention) condition, on the other hand, demonstrated only 65% accuracy. Educators involved in this study ultimately opted to implement the cognitive skills training techniques instead of the district-developed curriculum.

Further indicative of the role cognitive flexibility plays in education is the argument that how students are taught greatly impacts the nature and formation of their cognitive structures, which in turn affect students’ ability to store and readily access information.[32] A crucial aim of education is to help students learn as well as appropriately apply and adapt what they have learned to novel situations. This is reflected in the integration of cognitive flexibility into educational policy regarding academic guidelines and expectations. For example, as outlined in the Common Core Standards Initiative, which largely dictates school standards varying by state, educators are expected to present within the classroom “high level cognitive demands by asking students to demonstrate deep conceptual understanding through the application of content knowledge and skills to new situations”.[33] This ability is the essence of cognitive flexibility, and a teaching style focused on promoting it has been seen to foster understanding especially in disciplines where information is complex and nonlinear.[34] A counterexample is evident in cases where such material is presented in an oversimplified manner and learners fail to transfer their knowledge to a new domain.

Impact on Teaching and Curriculum Design

[edit]An alternative educational approach informed by cognitive flexibility is hypertext, which is frequently computer-supported instruction. Computers allow for complex data to be presented in a multidimensional and coherent format, allowing users to access that data as needed. Hypertext documents, therefore, include nodes – bits of information – and links, the pathways between these nodes. Applications for teacher education have involved teacher-training sessions based on video instruction, whereby novice teachers viewed footage of master teachers conducting a literacy workshop. In this example, the novice teachers received a laserdisc of the course content, a hypertext document that allowed the learners to access content in a self-directed manner. These cognitive flexibility hypertexts (CFH) provide a “three-dimensional” and “open-ended” representation of material for learners, enabling them to incorporate new information and form connections with preexisting knowledge.[35] While further research is needed to determine the efficacy of CFH as an instructional tool, classrooms where cognitive flexibility theory is applied in this manner are hypothesized to result in students more capable of transferring knowledge across domains.

Classroom application of cognitive flexibility must not rely solely on computer-based instruction. Researchers in the field advocate a teaching style that incorporates group problem-solving activities and demands higher-level thought.[36] According to this process, a teacher initially poses a single question in a number of ways. Next, students discuss the problem with the teacher and amongst themselves, asking questions. In forming these questions, students are actively brainstorming and recalling prior knowledge. At this point, the teacher provides specific conditions of the issue discussed, and students must adapt their prior knowledge, along with that of their peers, to generate a solution. Other curriculum designs tailored to young children such as “Tools of the Mind” incorporate practices which aim to improve students’ capacity to shift and prolong attention as well as think “outside the box” (i.e. generate creative solutions).

Learning Applications Beyond the Classroom

[edit]A vastly different application can be seen in the study of cognitive flexibility and video games. Examining the trait under the guise of “mental flexibility,” Dutch researchers observed that players of first-person shooter games (e.g. Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto) exhibited greater “mental flexibility” on a series of measures than did non-gamers.[37] The researchers posit that, while video game play may be controversial due to frequently graphic content, harnessing the effect of such games could lead to similar gains in various populations (e.g. the elderly, who face cognitive decline) and is therefore socially relevant.

Public awareness of cognitive flexibility has increased in recent years. As a result, several online programs marketed to those seeking to increase cognitive ability – by way of specifically focusing on cognitive flexibility training techniques - have been created. One such program, Luminosity, offers customers a “Core Brain Training” package that consists of sections focused on fundamentals, speed, accuracy, memory, attention, flexibility (purely a component of cognitive flexibility), problem-solving, and further training sections. Similar websites market “brain fitness” to customers and focus on improving visual and spatial processing, recall, attention, and executive functions as a whole. Presently, the efficacy of such programs requires further research and analysis before any clear benefits can be determined.

References

[edit]- ^ Scott, W. A. (1962). "Cognitive complexity and cognitive flexibility". American Sociological Association. 25: 405–414. doi:10.2307/2785779.

- ^ a b c Miyake, A. (2000). "The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex "frontal lobe" tasks: A latent variable analysis". Cognitive Psychology. 41: 49–100. doi:10.1006/cogp.1999.0734.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Deak, G. O. (2003). "The development of cognitive flexibility and language abilities". Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 31: 271–327. PMID 14528664.

- ^ Moore, A. (2009). "Mediation, mindfulness, and cognitive flexibility". Conscious Cognition. 18: 176–186. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bigler, R. S. (1992). "Cognitive mechanisms in children's gender stereotyping: Theoretical and educational implications of a cognitive-based intervention". Child Development. 63: 1351–1363. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01700.x. PMID 1446556.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Martin, M. M. (1995). "A new measure of cognitive flexibility". Psychological Reports. 76: 623–626. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.76.2.623.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cooper-Kahn, J.; Dietzel, L. "What is executive functioning?". Archived from the original on 2009-01-19. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Cartwright, K. B. (2002). "Cognitive development and reading: The relation of reading-specific multiple classification skill to reading comprehension in elementary school children". Journal of Educational Psychology. 94: 56–63. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.1.56.

- ^ Piaget, J. (1972). "The mental development of the child". In Weiner, I. B.; Elkind, D (ed.). Readings in Child Development. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 271–279. ISBN 0471925748.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Colzanto, L. S. (2006). "Intelligence and cognitive flexibility: Fluid intelligence correlates with feature "unbinding" across perception and action". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 13: 1043–1048. doi:10.3758/BF03213923.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Han, H. D. (1998). "Performance enhancement with low stress and anxiety modulated by cognitive flexibility". Korean Neuropsychiatric Association. 7: 221–226. PMID PMC3182387.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zelazo, P. D. (1998). "Cognitive complexity and control: II. The development of executive function in childhood". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 7: 121–126. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10774761.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Kirkham, N. Z. (2003). "Helping children apply their knowledge to their behavior on a dimension-switching task". Developmental Science. 6: 449–476. doi:10.1111/1467-7687.00300.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zelazo, P.D. (1996). "An age-related dissociation between knowing rules and using them". Cognitive Development. 11 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1016/S0885-2014(96)90027-1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Biederam J, Faraone S, Monutaeux M; et al. (2000). "Neuropsychological functioning in nonreferred siblings of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 109 (2): 252–65. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.252.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chelune, G. J. (1986). "Developmental norms for the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 8: 219–228. doi:10.1080/01688638608401314.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jensen, A. R. (1965). "Scoring the stroop test". Acta Psychologica. 24 (0): 398–408. doi:10.1016/0001-6918(65)90024-7.

- ^ Leber, AB (9 September). "Neural predictors of moment-to-moment fluctuations in cognitive flexibility". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105 (36): 13592–7. PMID 18757744.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hyafil, A (2009). "Two mechanisms for task switching in the prefrontal cortex". J Neurosci. 29: 5135–5142. PMID 19386909.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kim, C (Mar 30). "Common and distinct mechanisms of cognitive flexibility in prefrontal cortex". J Neurosci. 31 (13): 4771–9. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.06.013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Yehene, E (2008). "Basal ganglia play a unique role in task switching within the frontal-subcortical circuits: evidence from patients with focal lesions". J Cogn Neurosci. 20 (6): 1079–93. PMID 18211234.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Morton, JB (2009). "Age-related changes in brain activation associated with dimensional shifts of attention: An fMRI study". Neuroimage. 46: 249–256. PMID 19457388.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Steinglass, JE (2006). "Set shifting deficit in anorexia nervosa". J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 12 (3): 431–5. PMID 16903136.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Etchepareborda, MC (2004). "Cognitive flexibility, an additional symptom of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Is it a therapeutically predictive element?][Article in Spanish]". Rev Neurol. 38 (Suppl 1): S97-102. PMID 15011162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chamberlain, SR (2005). "The neuropsychology of obsessive compulsive disorder: the importance of failures in cognitive and behavioural inhibition as candidate endophenotypic markers". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 29 (3): 399–419. PMID 15820546.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kriete, T (2005). "Impaired cognitive flexibility and intact cognitive control in autism: A computational cognitive neuroscience approach". In Proceedings of the 27th annual conference of the cognitive science society: 1190–1195. doi:10.1.1.123.5160.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bühren, K (2012). "Cognitive flexibility in juvenile anorexia nervosa patients before and after weight recovery". Journal of Neural Transmission. 119 (9): 1047–1057. doi:10.1007/s00702-012-0821-z.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stalnaker, TA (2009). "Neural substrates of cognitive inflexibility after chronic cocaine exposure". Neuropharmacology. 56 (Suppl 1): 63–72. PMID 18692512.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Greenwood, PM (2007). "Functional plasticity in cognitive aging: review and hypothesis". Neuropsychology. 21 (6): 657–73. PMID 17983277.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Masley, S (2009). "Aerobic exercise enhances cognitive flexibility". Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 16: 186–193. doi:10.1007/s10880-009-9159-6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Diamond, A. (2007). "Preschool Program Improves Cognitive Control". Science. 318 (5855): 1387–1388. doi:10.1126/science.1151148.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Boger-Mehall, Stephanie R. (2007). "Cognitive Flexibility Theory: Implications for Teaching and Teacher Education". Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "33. Common Core State Standards Initiative Standards-Setting Criteria" (PDF).

- ^ Chikatla, Suhana (2007). "Cognitive Flexibility Theory". University of South Alabama. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Spiro, Rand (1992). "5". In Duffy, Thomas M. (ed.). Constructivism and the Technology of Instruction: A Conversation (1 ed.). Routledge. pp. 57–75. ISBN 0805812725.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stephens, Elizabeth Campbell (1995). "The design, development, and evaluation of Literacy education : application and practice (LEAP) : an interactive hypermedia program for English/language arts teacher education" (Book, thesis/dissertation, manuscript). University of Houston M.D. Anderson Library Houston, TX 77004 United States: University of Houston. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Colzato, Lorenza S. (2010). "DOOM'd to switch: superior cognitive flexibility in players of first person shooter games". Front. Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

Wlbaccus (talk) 06:02, 10 October 2012 (UTC) Wlbaccus (talk) 18:55, 8 October 2012 (UTC) Wlbaccus (talk) 01:33, 29 October 2012 (UTC) --Wlbaccus (talk) 15:17, 30 October 2012 (UTC)

Comment to the editors of this text

[edit]I am not a legal expert, but revealing the procedure in WSCT might be a copyright infringement and it will destroy its clinical value. Please reconsider! Lova Falk talk 18:36, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

Comment to Lova Falk

[edit]Lova Falk, thank you for your input. As graduate students working with the APS wiki initiative, we had not considered that aspect of informing the public about the WCST. We'll take this into consideration before making and changes to the site.--Wlbaccus (talk) 18:56, 29 October 2012 (UTC)

Two more comments to the editors of this text

[edit]Hi there! Two more comments:

- Please, don't use capital letters only in the first word of the headings (apart from names etc). For instance: Neural underpinnings

- We don't use wikilinks in the titles of sections and subsections. Either a wikilink is put the first time the term comes in the text, or you can write {{main|article}} underneath the title. For instance:

===Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST)===

{{main|Wisconsin Card Sorting Test}}

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test bladibladibla...

gives:

Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST)

[edit]The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test bladibladibla...

Thank you! Lova Falk talk 17:19, 30 October 2012 (UTC)

GA Review

[edit]| GA toolbox |

|---|

| Reviewing |

- This review is transcluded from Talk:Cognitive flexibility/GA1. The edit link for this section can be used to add comments to the review.

Reviewer: TheSpecialUser (talk · contribs) 10:29, 1 November 2012 (UTC)

- Giving the issues in few minutes. Thanks! TheSpecialUser TSU 10:29, 1 November 2012 (UTC)

I fear that a lot of work should be done on the article in order to get this upto GA standards and I'm extremely sorry that this'll be a quick fail. Here are the primary reasons for the failure:

- Per WP:LEAD, it should summarize the article and at present it is only giving 3 definitions by different authors and not by any world renowned organization etc.

- Ref issues - there are plenty of them but all of them are not well formatted and 90%+ of them are not readable. They will require ISBN or any link so that the material cited could be verified.

- I cite few grammatical errors in the prose as well as copyediting is required from someone who is expert in the topic

- MoS fixes are needed a lot. Example, the headings and sub-headings should not be in italic form.

- Despite of 80+ refs, many facts remain unsourced in the article. If you are aiming for GA, each and every fact should cite at least one ref to reliable source using well formatted citation.

I appreciate the efforts but unfortunately, this article is not near to GA status; these issues cannot be addressed easily. Once addressed the concerns above, anyone can re-nominate it. Thank you. TheSpecialUser TSU 10:51, 1 November 2012 (UTC)

These changes have been addressed. Please see the updated page. Obrien.sarah (talk) 05:23, 10 December 2012 (UTC)

1. Citations. A good article should not have [citation needed] tags. 2. Also, the formatting is inconsistent, this is a minor point, but inline citations should be after the punctuation with no spaces. 3. Further, especially the lead section covers a lot of ground, but only provides one citation. It would be great to have a few more references to back up the many claims being made. 4. Formatting. Headings should be full page width (neural underpinnings is cut short by the image.) 5. You could add the psychology sidebar to the article (copy it from another article, e.g. the deferred gratification article). If you do this, the TOC looks a lot better if it is directly under the lead section.

These issues listed above have been corrected. Please refer to the main article page. Obrien.sarah (talk) 04:06, 11 December 2012 (UTC)

GA review on hold CabbageX (talk) 21:35, 13 December 2012 (UTC)