Talk:Bulgarian language/Archive 1

| This is an archive of past discussions about Bulgarian language. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

| Archive 1 | Archive 2 | Archive 3 |

Moods

There seem to be at least 6 grammatically distinct tenses in the subjunctive. However, some of them serve primarily in the formation of coplex verb forms like "I want to do" while others are colloquially used only to convey doubt (impossible to translate). Maybe these last ones should be separated their own dubitative mood, since they are not only semantically, but also gramatically distinct.

Consonants

Somebody please fix the table with the consonants because it doesn't have the dz sound.

Bulgar

I've weakened the claim that the suffixed article is an inheritance from Bulgar. First I've heard of it. But it might be true, so I haven't removed it entirely. I thought the orthodox story was that since Romanian, Bulgarian, and Albanian form a Sprachbund for the article, and neither the Romance nor Slavonic branches otherwise have it, it must have been an Albanian innovation. I don't know anything about Bulgar, not even what branch of 'Altaic' it was in, but neither Mongolian nor Turkish has a definite article. (Turkish omits accusative marking on indefinite objects.) Gritchka 19:30 26 Jul 2003 (UTC)

- Actually, Romanians and Bulgarians had direct commercial/cultural links since the Bulgarians came in the Balkans and about 1000 years ago there was even a Romanian-Bulgarian common state, but both Romanians and Bulgarians had almost no link with Albanians that could bring an article.

- A better explanation is that the Tracians had this suffixed article since Thracians were living in Romania, Bulgaria and Albania. Albanians may have directly inherited it (since Albanians are direct descendents of the Thracians), Romanians kept it from the Dacian language (a Thracian dialect) into the Latin after the Roman conquest and Bulgarians, establishing themselves in a region already inhabited by Thracians, add it into their language. Bogdan 11:52, 19 Sep 2003 (UTC)

- A very similiar suffixised article exists in Aramiac and other west semitic languages, a diliact of Aramiac which was lingua franca in a large area circa 1st cent may have gotten in the Bugarian, including a great mixure of people from turkey for example. AFAIK, there aren't definate conclusions yet.

- I'll start an article about Balkan linguistic union in the next week. :-) Bogdan | Talk 10:59, 22 Jun 2004 (UTC)

It may be helpful to include Bulgarian grammar here. [[User:Poccil|Poccil (Talk)]] 22:36, Jun 20, 2004 (UTC)

How many consonant phonemes?

So how many consonant phonemes are there in Bulgarian? 33 as declared or 36 as in the table? Zsigri (talk) 07:01, 22 January 2009 (UTC)

Macedonian naysayers

In Routledge's The Slavonic Languages, edited by Bernard Comrie, the section on Bulgarian explains that it is really only the Bulgarian and Greek linguists who do not recognise Macedonian as a separate language, whilst the general community of linguists does. I've highlighted that accordingly. Crculver 10:08, 22 Jun 2004 (UTC)

History of Bulgarian

- I've updated the history of Bulgarian using the aforementioned work The Slavonic Languages. I also emphasized that while Bulgarian is descended from Old Church Slavonic, so as other languages in the Balkan region, and therefore the name "Old Bulgarian" is considered an anachronism by reputable modern linguists. Crculver 16:01, 10 Aug 2004 (UTC)

- Excellent. Juro 16:16, 10 Aug 2004 (UTC)

VMORO

Generally agree with most of the edits but I've made some corrections. 1. A.Schleicher, M.Hatala and L.Geitler in the 19th century talk about Old Bulgarian and I have reflected that. 2. No Bulgarian linguist (and as far as I am aware, no Greek one) has ever recognised the Macedonian language, so the definition "most" is incorrect.

Just an observation

It's so comfortable that you two (Crculver and Juro) turned out logged at the same time and Crculver just happened to look the things we were arguing about with Juro in the dictionary...

Are you suggesting that Juro is identical with Crculver?!!! Juro 11:46, 11 Aug 2004 (UTC)

- I think it's silly to suggest that there's some sort of conspiracy. In the summer I spend a good 16 hours a day at the computer, so there's no surprise that I am logged in at the same time as someone else. Furthermore, I am a philologist, so it's quite understandable that I have a large library which I can consult for my work, including a number of works on Slavonic comparative linguistics. Incidentally, you would do well to take a look at some of those works, because you are generally editing from a Bulgarian-centric viewpoint, whereas I would prefer you support the international viewpoint that, among other things, recognises Macedonian as a separate language for centuries. Crculver 14:32, 11 Aug 2004 (UTC)

- All linguists in Greece and Bulgaria are united in Not recognising the Macedonian language, as well as some foreign linguists (certainly a minority), for ex. Austrian Otto Kronsteiner. What my opinion is is irrelevant, I am just stating the facts. If I edited from a "Bulgarian-centric viewpoint", I would have said smth like "Macedonian language does not exist and has never existed, it is a southwestern Bulgarian dialect". As for "the international viewpoint, which recognises Macedonian as a separate language for centuries", that is certainly untrue in its "centuries" part.

- Articles with definite article are something normal and used without any help words,

- e.g. English "the new one" is Bulgarian 'noviat'.

This phrase is not very clear. What do you mean by "Articles with definite article" ? Noviat looks like an adjectiv (novi) + definite article (-iat). Bogdan | Talk 13:12, 12 Aug 2004 (UTC)

Also, I was wondering whether the meaning is equivalent to the Romanian: (Noul = adj. "nou" + article. "-l")

example:

Rom: "Noul este superior vechiului".

Eng: "What's new is superior to what's old".

Bogdan | Talk 13:21, 12 Aug 2004 (UTC)

It was a mistake, it is an adjective.

As for the sentence, it's pretty much like Romanian: "Новото е по-добро от старото" ново - new, neutr. sing то - neutr. art.

Though I must confess the sentence sounds a bit strange in Bulgarian

"Bulgarian demonstrates several linguistic innovations that set it apart from other Slavic languages, such as the elimination of noun declension, the development of a suffixed definite article (possibly inherited from the Bulgar language), the lack of a verb infinitive, and the retention and further development of the Proto-Slavic verb system. There are various verb forms to express non-witnessed, retold, and doubtful action."

I replaced 'innovations' with developments. The connotation of 'innovation' implies an improvement upon previous circumstances. The word 'development' captures the same denotation without implying improvement. It is important to highlight Bulgarian's unique characteristics in comparison to other languages in the surrounding area (Macedonian, Albanian, Romanian) and in contrast to other languages of the Slavic branch, but this should be done in neutral language. It is no more an innovation of Bulgarian's to move away from synthetic structure than it as an innovation of Estonian's to move toward it (from agglutinative).

Nationalism and linguistics do not go well together. Norwegian and Danish are mutually intelligible and far more dialects than separate languages, but one does not see any hissy-fits over the matter on their wiki articles.

- the word 'innovations' is used in this mannar in the lingiustic jargon, meaning something like 'a mutation ie, not borrowed or inherited', and does not try to imply improvement in such context, I believe this was naive jargon use rather than 'nationalism'

- That's right, there is nothing remotely nationalistic or emotional about the word "innovation" as used in a linguistic sense. It simply means that a grammatical feature was newly created and introduced, and not borrowed from another language or inherited from a parent language. It's an innocent word.

- — Stephen 12:03, 4 Dec 2004 (UTC)

Bolgar words

Are there any words in Bulgarian that definitely derive from the Bolgars? Alexander 007

- If you mean these: [1] and [2], but I warn you that many words are wrongly added. Bogdan | Talk 11:40, 26 Nov 2004 (UTC)

Yes. Many of those alleged "Turkic" words are in fact from other sources (Romanian, Slavonic, possibly even Thracian, etc.). In fact, one of these lists (if not both) I've looked through before. I was amused to see the attempted derivation of calugar from Turkic. Alexander 007

Elimination of Noun Declension

"Bulgarian demonstrates several linguistic developments that set it apart from other Slavic languages, such as the elimination of noun declension..."

- Isn't the Vocativus case preserved in Bulgarian? as in "дай ми бабо, дай ми я", a google search shows these forms are still used online.

Of course the Vocative case is still preserved, it is used regularly, but there are no other cases.

Old Church Slavonic connection needs work

This article needs to explain that while some Old Church Slavonic texts can be termed Old Bulgarian, others cannot. Cyril and Methodius never set foot in Bulgaria, coming from Thessaloniki. In instructing the Slavs of Moravia they used general Proto-South-Slavonic, and the translations and writings which were created by the Moravian students (such as the Kiev Folia) were too far north to suffer any Bulgarian influence. It is only in the texts first written after the explusion within the Kingdom of Bulgaria that there is any influence from the language of the Bulgarians. Furthermore, this explanation should be done succinctly, as anything too specific would rather go on the Old Church Slavonic page. Crculver 10:59, 11 Dec 2004 (UTC)

I'm afraid we know who will not allow any mention of these facts ...Juro 22:03, 11 Dec 2004 (UTC)

I've gone ahead and made a large redaction. I have removed any information which is too pertinent only to Old Church Slavonic. VMORO et al, you are welcome to move those statements to the Old Church Slavonic article and put them into better shape there. Conciseness is to be desired in an encyclopedia article, and if someone wanted to see polemics about OCS, they can look at the OCS article. No use wasting them time of people who are mostly reading about later forms of the language. I have tried to clarify that only the OCS writings made within Bulgarian can be fairly well called "Old Bulgarian", as the manuscripts from the Moravian tradition have no connection to Bulgaria at all, but I might try to polish this more later Crculver 00:54, 12 Dec 2004 (UTC)

- I agree with you with the exception of one single thing: The phonological and grammatical peculiarities found in Old Church Slavonic are characteristic only for Bulgarian, what do you mean by terming them vaguely South Slavic? As from the 9th/10th century we can talk about several distinct Slavic nations, and if South Slavic can be deemed an term for the 6th and the 7th century, it is not for the 9th century. I'll see what I can do to shorten the text here tomorrow. VMORO

- I will be removing the things again from the article. If you want to fight this, I will submit this to Requests for Mediation. I have at my desk a mountain of scholarly works, quotation of which will serve to show that you are attempting to deny the real state of things for nationalistic reasons. I can also present the testimony of several professors of comparative Slavonic linguistics who are unhappy with this kind of slant.

- And I will repeat once again, Cyril and Methodius never set foot in the Kingdom of Bulgaria. Ever. Any "Bulgarian features" which show up in the northern OCS manuscripts can only be due to the fact that they are general South Slavonic features, found at the time among the non-Bulgarian Slavonic community of Thessaloniki. Crculver 03:00, 12 Dec 2004 (UTC)

- And which is:...??? VMORO

- I'm going to spell this out very simply, pay attention. 1) Cyril and Methodius were from Thessaloniki, they never went to Bulgarian. 2) Therefore, their own language cannot be called "Old Bulgarian". 3) The Kiev Folia, the text of which was produced by their Moravian students, contains many of the same linguistic features present in Bulgaria, but was in no way influenced by Bulgarian. 4) Therefore, those linguistics features cannot be called "Bulgarian", for they are not specific to it, but must be generally called South Slavonic. This is what reputable linguistics do. See Schlamstieg, Nandris, Huntley, Schenker, etc. etc. If you disagree with this, you not only disagree with the bulk of comparative Slavonic scholarship (which already suggests you're wrong), but with simple logic. Crculver 03:26, 12 Dec 2004 (UTC)

- May be I should spell out my question for you: if they are not Bulgarian, what were they? And since when the language of a people corresponds to its borders? And sure, Juro, that separate Slavic languages can be distinguished long before the 11th century, there is something called comparative linguistics. VMORO

- They are "South Slavs". That is what they are called by reputable scholars. They cannot be called Bulgarians because Thessaloniki was outside of the area where the Bulghars, the biggest element of a distinct Bulgarian people back then, settled. Incidentally, Juro is correct. There are comparative linguists who venture that Common Slavonic lasted up to the 13th century. I'll find some names for you. Crculver 04:23, 12 Dec 2004 (UTC)

I am actually satisfied with your answer - for the time being. I haven't forgotten my promise. Cheers, VMORO

- Exactly... I can only add that it is even disputed whether one can distinguish separate Slavic languages before the 11th century... Juro 03:45, 12 Dec 2004 (UTC)

Online Dictionary

There should be a better online Bulgarian-English dictionary than the one provided by the link below the article. Alexander 007

- I agree, it's really horrible. It would be better to have nothing at all. There is an online dictionary at http://sa.dir.bg/ that is very fast and easy to use. It needs work, but it's useful just as it is.

- — Stephen 13:06, 31 Dec 2004 (UTC)

Thanks. The Dictionary you linked to is what I was looking for.Alexander 007 02:02, 1 Jan 2005 (UTC)

Palatal plosives

Quote:

- Soft /g/ and /k/ (/gʲ/ and /kʲ/, respectively) are articulated not on the velum but on the palatum and are palatal consonants.

In that case, shouldn't they be /ɟ/ and /c/ rather than /gʲ/ and /kʲ/?

—Naddy 17:35, 10 Mar 2005 (UTC)

- Are /ɟ/ and /c/ plosives? 'Cause as far as I remember they were fricatives whereas k' and g' are plosives. VMORO 20:56, Mar 11, 2005 (UTC)~

- /c/ and /ɟ/ are plosives, though to speakers of a language without them they'll sound a little like affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/. But the palatalised consonants in Slavic languages are different from palatal consonants, as I understand things. Palatal /c/, for example, is made with the tip of the tongue touching the palate, while palatalised /kʲ/ seems to me to be made the back of the tongue touching the velum, as with a regular /k/, but slightly further forward than /k/; foreign learners are encouraged to do this by simultaneously pronouncing a palatal approximant /j/... so, in short, the article's wrong. ;o) J.K. 07:34, 12 Mar 2005 (UTC)

- You are free to correct it in this case:-)))) Your assumptions are basically correct with one exception - soft "k" and "g" are pronounced much more forward than the hard ones and they are articulated not with the back of the tongue but with the middle part of it. VMORO 13:40, Mar 12, 2005 (UTC)~

- So how do the Polish palatals ź [ʑ], ś [ɕ], dź [dʑ], ć [tɕ] relate to the Bulgarian ones? Is, say, [ʑ] vs. [zʲ] just a difference in notation or are these actually different consonants? —Naddy 12:56, 21 Mar 2005 (UTC)

I'll have to answer again that I don't know as I am not a Slavist and do not have a good idea of Polish consonants. [zʲ] in Bulgarian is a normal "z" with a [ʲ] nuance, the Polish one seems to be a bit more like /ʒ/... VMORO 22:04, Mar 21, 2005 (UTC)~

I'll have to correct you - k' and g' are indeed palatals (at least in Bulgarian) and are articulated on the palatum. I am a linguist, though unfortunately not a Slavist:-(( VMORO 19:02, Mar 13, 2005 (UTC)~

- Hmmm. I take your point, but nevertheless those sounds are quite distinct from /c/ and /ɟ/. It may only be a matter of the part of the tongue they're articulated with (tip and/or blade for /c/ and middle for /kʲ/), but as things stand people still might mix them up. How to phrase it to make the difference clear? J.K. 23:35, 13 Mar 2005 (UTC)

- I don't have even the slightest idea:-))) I guess the greatest confusion will be the link to voiced/voiceless palatal plosive as people will surely think then it is /c/ and /ɟ/ we are talking about and not k' anf g'...

VMORO 15:07, Mar 15, 2005 (UTC)

Alright, I think that we really should have [c] and [ɟ] instead of /kj/ and /gj/ as they are palatals in Bulgarian. OK, [c] in BG doesn't sound exactly like hungarian [c] (<ty>), but there has got to be some consistency, it doesn't make sense to have [c] in Greek & Slavo-Macedonian and [kʲ] in Bulgarian since in all 3 languages 'k' before front vowels is a palatal consonant—[c]—and not a velar one. Also there is a slight difference in the place of articulation of к and г before о/у and а/ъ. In the former case they're articulated on the velum and in the latter the tongue slightly shifts towards the palate.

Cyrillic italics vs. bold or underlining

Just a note about the italicizing of Bulgarian examples in the Morphology section.... I agree that the italics look nicer than bolding, but they are a problem for anyone who is not comfortable with the Cyrillic script. I have no problem with them, but most foreigners seem to have difficulty reading them. Consider, for example, глътки на дърветата, глътки на дърветата, глътки на дърветата, глътки на дърветата, глътки на дърветата, глътки на дърветата. In my opinion, we should not be using italics for any of the Bulgarian examples, but should use one of the other styles that I have shown here. —Stephen 11:47, 18 Mar 2005 (UTC)

- Yeah, it will probably cause difficulties for them, I chose italics only because the other language articles I checked use italics when examples from the mother tongue are quoted. If you consider that underlining or the two other scripts you quoted are a better option, feel free to reformat the text. VMORO 13:46, Mar 19, 2005 (UTC)~

Clitic doubling

I'm the editor of the article on clitic doubling, but unfortunately I only know about it as it works Spanish. Could someone enlighten me about clitic doubling in Bulgarian? I know that it exists and it has certain particular rules,[3] but that's it. I'd like to have some input from native speakers. Clitic doubling is, roughly, when you mention e. g. the object of a verb, and you also use a pronoun that refers to it: "I gave her a present to my mother." It'd be nice to mention clitic doubling in the Bulgarian language article, too. --Pablo D. Flores 15:24, 9 May 2005 (UTC)

- There is clitic doubling but it is mostly emphatic. You could say: Аз го дадох подаръка на майка ми - I gave it the present to my mother. Or: Аз й го дадох подаръка на майка ми - I gave her it the present to my mother. If one speaks formally, the sentence will, however, have to be: I gave the present to my mother. It is rather colloquial and that's why it is not treated extensively in grammars. VMORO 23:09, Jun 21, 2005 (UTC)

- Thanks a lot. I've added the info to the article in a new "Syntax" section. However, now clitic doubling is all I know about Bulgarian syntax. :) I've marked the section as stub. --Pablo D. Flores 10:32, 22 Jun 2005 (UTC)

- I have fixed the examples to use "ѝ" instead of "й", as that is the correct way to write the single dative female pronoun ("to her"). Lots of Bulgarians use "й" instead of "ѝ", as the traditional Bulgarian keyboard layouts do not offer an easy way to stress words. However, using "й" or just "и" is incorrect. It really should be "ѝ". I also updated the section for Word Stress to mention this rule. Ironcode 12:44, 19 May 2007 (UTC)

Note:

Аз (го) дадох подаръка на Мария. (lit. "I gave it the present to Maria.") Аз (ѝ го) дадох подаръка на Мария. (lit. "I gave her it the present to Maria.")

I'm a native speaker but I can't quite grasp the idea the author of the text is implying so I can't give a better example. Please elaborate on the concept of clitic doubling and whether it implies the addition of the parenthesised words above or their omission. If these words are included the result is a constuct that would generally only be used by an illiterate person. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 84.21.220.54 (talk) 16:28, 19 February 2009 (UTC)

Vowels

Kostja, there are three different types of "a" (or may be even many more), a front one, a central one and a back one. In languages which don't differentiate between them, they are just allophones.

For the second, phonetics is a relative science and in different languages, the same vowels/consonants are described in a completely different way. For one reason or another, "a" in Bulgarian is considered a central vowel - probably for the sake of conveniency as it makes pair with "ъ", which can not be described as anything else but a central vowel. You can check this in any textbook in Modern Bulgarian or any book in Bulgarian phonetics. When I wrote the Bulgarian language article, I have used primarily a Western textbook which also classified the vowel as central. VMORO 23:19, Jun 21, 2005 (UTC)

I changed the mid vowels (e and o) to be mid-high instead of mid-low, all of the literature I've read about Bulgarian (and I'll admit it's not much) say nothing about the vowels being mid-low. If someone can produce a source that indicates the vowels as mid-low then it'll be appropriate to change it back.AEuSoes1 03:27, 20 September 2005 (UTC)

- I am really not concerned about mid-low and mid-high, in a language with lax vowels such as Bulgarian, this is irrelevant. However, you keep changing the vowels [ɛ] [ɔ] to plain e and o and this is incorrect. e and o are much higher (or more closed) than [ɛ] and [ɔ] and they don't exist in Bulgarian or in any other Slavic language (may be with the exception of Slovenian). There are several grades of shading between o and u and a and @ (2 in the first pair and 3 in the second one), depending on the position of the vowel with regard to the stressed syllable. And finally, shading between i and e is the norm in most Eastern Bulgarian dialects but it is not ALLOWED in the formal language (for example, not [rika] but only [reka] without any shading). I have used mostly a compilation by Routledge on all Slavic languages - for the sake of English terminology. Otherwise, I draw on the classes in Modern Bulgarian which I've had at the university - I am a linguist. VMORO 21:27, 23 September 2005 (UTC)

- All right, I guess that works. Since those are the vowels, I'll change the whole article to fit it since the changes that you are holding to make the article inconsistant. I will, however, revert my other changes. The phrase "approaching each other, though without merging completely" doesn't make sense. "Allowed" is a prescriptive term and if it's only for the formal language then that should be in the article. AEuSoes1 21:05, 26 September 2005 (UTC)

- The phrase which you questioned - There are several grades of shading between o and u and a and @ (2 in the first pair and 3 in the second one), depending on the position of the vowel with regard to the stressed syllable - if you can think of a better way to put it, pls do. VMORO 08:33, 27 September 2005 (UTC)

- I think the value for ъ in stressed position should be marked as [ɘ] or at least as [ɤ̟] given that cardinal [ɤ] is a back vowel, whereas ъ is central and it kinda makes no sense. Also, all possible srcs I've found online give sound examples of [ɤ] that sound really distinct from BG ъ. Here are some: src 1, src 2, scr 3. Also, in 'Houston/Хюстън' <ъ> is NOT stressed therefore it should be marked as [ə] (or even [ɐ] if you want, but this only applies to really careful and well-articulated speech).

Perfective/Imperfective Pairs

Regarding the paragraph:Most Bulgarian verbs have perfective-imperfective pairs (imperfective<>perfective: идвам<>дойда “come”, уча<>науча “study”). Perfective stems are usually formed from imperfective ones by suffixation or prefixation.

I don't think pairs of the kind уча<>науча are considered perfective-imperfective pairs anymore. Although науча is derived from уча using a prefix, these are considered two separate words with two separate, although close, meanings. The imperfective counterpart of науча is научавам. These two are considered by some to be different forms of the same word. Уча is an imerfective verb without perfective counterpart. The prefix на- adds a sense of completion, but IMHO that is not equivalnt to "perfectiveness". The verb уча refers to the process of just studying something, while the verb науча refers to the proces of studiyng and rememberring something in its entirety. The later process may be reffered in both perfective (науча) and imperfective manner(научавам).

It is the same way with other preficess, and much easier to comprehend when the meaning the prefix adds to te word is not completion: from пиша (to write): запиша - записвам (to write down), опиша - описвам (to describe), подпиша - подписвам (to sign), etc., I dont see a reason why the pair напиша - написвам should be treated differently, or as in the example above, науча - научавам.

I wanted to hear some oppinions before I made any changes.--Beesuke 6 July 2005 14:42 (UTC)

- You are partially right but only partially. What is the perfective counterpart of уча in this case? Non-existent? науча may be a separate word but with regard to уча, it is used as the verb's perfective counterpart. науча can form a perfective-imperfective pair with научавам, as well - I don't see what is so confusing in that... A language is, anyway, a living organism, formal criteria can facilitate its understanding but they are not all-valid. VMORO 08:43, 27 September 2005 (UTC)

- It's better to think of verbs like уча, науча, научавам or пиша, напиша, написвам as a triad - the first verb is imperfective, the second - perfective and the third - secondary imperfective, because in most other non-slavic languages they would be translated by just one verb (for example in English the slight change in meaning which occurs when adding the prefix на- is unimportant and the last three verbs all mean "to write"). Arath 15:10, 18 August 2006 (UTC)

- You are partially right but only partially. What is the perfective counterpart of уча in this case? Non-existent? науча may be a separate word but with regard to уча, it is used as the verb's perfective counterpart. науча can form a perfective-imperfective pair with научавам, as well - I don't see what is so confusing in that... A language is, anyway, a living organism, formal criteria can facilitate its understanding but they are not all-valid. VMORO 08:43, 27 September 2005 (UTC)

There are some verbs in Bulgarian thatbhave only imperfective stems - like уча. Adding the prefix in this case changes the meaning - slightly.

population

Does anyone have a source for the native speaking population of Bulgarian? Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece, Romania, and Moldova together constitue 6.7 million, but this article has 16 million (presumably not all native speakers). Thanks, kwami 07:45, 3 November 2005 (UTC)

The population of Bulgaria is 7.7 million, however how many speakers of Bulgarian exist in Greece, Turkey, Macedonia, Albania, Moldova, Ukraine and Romania is something I'm afraid nobody can tell for sure. Numbers vary a lot.

I think that the Bulgarian speaking population is even around 10 million people, and Macedonian language is highly inteligible with Bulgarian. Actually a lot of specialists think that it's a dialect of Bulgarian. For example in Northern Greece, in the European part of Turkey, in the Dobrudja (Добруджа) region in Romania and in Southeastern Serbia thirty or fourty years ago the main population spoke Bulgarian. In official documents are declared 7.7 million speakers because of political reasons. In short: on the Balkans everything is too confused, so I think we should use only official facts because other nations can feel offended.Trutnuth 12:35, 21 August 2007 (UTC)

Common expressions

Could someone who speaks Bulgarian check on my edit? I'm not sure if I'm legitimatizing a vandal or not. Thanks. Melchoir 05:50, 7 November 2005 (UTC)

Your list of expressions is OK! L.Kolev

Spelling Reform of 1945

Can anyone please write something about the spelling reform of 1945? Particularly what interets me is:

- How were yat and yus pronounced before they were removed?

- Was the iotated yus used considered a separate letter? How was it pronounced?

- Was the Ъ at the end of the word completely unpronounced in speech by that time? When did disappear from speech?

- I saw in an old dctionary that the word for "language" was written язикъ and now it is written език. What was the rule for replacing я with е?

- What other changes were made?

There are also the non-linguistic matters:

- What was the public reaction in Bulgaria?

- Who initiated the reform? The Russians or someone else?

- Are there today any advocates for going back to the old spelling?

Thank you very much in advance!--Amir E. Aharoni 20:43, 8 November 2005 (UTC)

- The yus was (and still is) pronounced as Ъ in standard Bulgarian, мъка (variations у, мука in the Torlak dialects, a, мака in the Macedonian dialects and o, мока in the Rodopian dialects.

- There was a rul that the yat should be pronounced the way it's written now but it was never concidered obligatory - the tsar for example and a lot of the MPs followed strictly the western pronunciation - бел - бели, and not as the rule says бял - бели.

- The iotated yus was concidered a separate letter but was removed by Marin Drinov in his reform in the 1880s.

- The final Ъ lost its pronunciation in the 15th century.

- Язикъ is a russism, the norm was езикъ, now език.

- The reform was generally accepted cause it was seen as necessary but a lot of speakers of western dialects and especially the Macedonians from Pirin Macedonian and the diaspora wanted to keep the yat as a unifing letter although not on its ethimological place but only when the western and eastern prounuciantion differ. But there wasn't really any room for public debate in 1945.

- The reform was purely Bulgarian deed.

- There are some right wing cultural and political organisation (like VMRO-BND) which advocate reintroduction only of the yat. Miko Stavrev.

Actually the spelling reform had a trial run in 1921-23 under the Stamboliyski government. It was abolished after the June 9, 1923 coup. --Vladko 07:56, 23 February 2007 (UTC)

- ѫ was pronounced as ъ at least where we have it today, here are a few examples from something printed before 1945: хвѫрчѫ, спѫ, бѫдѫще, потѫнала, рѫка, мѫгли гѫсти, дѫбѫтъ and so forth. As for the yat, now this is a tough one, based on what I've heard from migrants who've left bulgaria before 1945 I'd say that it was pronounced as 'е' in positions where there is я today, those illiterate morons who call themselves 'journalists' and who constantly mangle the BG language made fun of Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha for saying „вервайте ми” instead of „вярвайте ми”. However, it should be clear that my observations are based mostly on listening to people who used to live in Sofia before they fled. I guess back then speaking in your local dialect was not deemed as something negative. Also, my guess is that in the eastern half of the country it was pronounced as 'я', but not in every single position of course. I can't possibly imagine anybody pronouncing „съвѣсть” or „цѣна” or „очитѣ” with /ja/ (well, at least in the late 19th/early 20th century).

- I managed to find Ѭ only in Найден Геров's dictionary, in the two other books I have from before 1945 (one from 1932 and the other from the 1880s) there is no such letter. In Gerov's dictionary there is a separate entry for Ѭ so my assumption is that it had the status of a separate letter and it was pronounced the way 'я' is. However, you should note that he considers „ш, ч, ж” to be 'soft' consonants and he writes it (along with я) after them.

- All weak ers began to drop out of pronunciation during the Old Bulgarian period and by the end of it they were gone. For your information weak are the ers:

- In word-final position.

- Before a syllable containing a vowel different than er.

- All odd ers in a word with more than 2 consecutive er-containing syllables.

- Erm, pretty much the same rule that lead to using the north-eastern dialects as a basis for the standard language... I guess. You can still hear the word „язик” in western bulgaria.

- Well what you've written is not entirely true, because today's Bulgarian ъ does not represent only big yus, it also represents the yers. For example the word сърце has never been pronounced сѫрце. You can see that in many Slavic languages it is not written at all: срце (in Serbian and Macedonian, it would be сурце and сарце if it contained ѫ). In Russian ѫ gave у and ъ gave о, so: сънъ gave сон, рѫка - рука, ѫгълъ - угол, сѫобщение - сообщение. So it is хвърчѫ and спѭ, not хвѫрчѫ, спѫ,(you say аз спя not аз спа). Here´s a list that might help you. Arath 16:14, 8 April 2007 (UTC)

- Also. In the eastern dialects ѣ is pronounced я when it is stressed and the next syllable does not contain е or и (of course there are some exceptions) . That's why nobody pronounces „съвѣсть”, „цѣна” and „очитѣ” with я, because ѣ is not stressed. Arath 09:30, 9 April 2007 (UTC)

Cyrillic in Wikipedia

Please see the new page at Wikipedia:Naming conventions (Cyrillic), aimed at

- Documenting the use of Cyrillic and its transliteration in Wikipedia

- Discussing potential revision of current practices

- Italics in Cyrillics:

- A guideline on whether or not to italicize Cyrillics (and all scripts other than Latin) is being debated at Wikipedia talk:Manual of Style (text formatting)#Italics in Cyrillic and Greek characters. - - Evv 16:14, 13 October 2006 (UTC)

Article

To my consideration the deffinite article suffix is not used in that way! The article ending depends on what the word ends. You have "bashta" (father), which is a noun in masculine gender, but the definite form is "bashtata( the father). "Dyado" (grandfather), again in masculine gender has a defenite form of "dyadoto, etc. As I am no linguist please consult the Petar Pashov book "Prakticheska balgarska gramatica" (Practical Bulgarian Grammar).

Tourist phrases

I removed the section containing "common phrases". If you wish to show examples of Bulgarian, please do so by excerpts of literary works, not by listing ways of how to buy bread or to greet someone. We already have list of common phrases in various languages for this purpose, eventhough I personally think it belongs in a wikibook, rather than an encyclopedia.

Peter Isotalo 12:59, 27 December 2005 (UTC)

Removal of referenced material

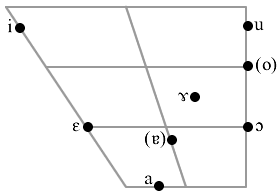

The IPA handbook has been removed from the reference section twice now, along with reverts of the very useful and illustrative vowel chart and kwami's corrections concerning some of the fricatives. I really don't understand the point of removing the only source the article has in favor of innacurate information as well as the information attached to it.

Peter Isotalo 00:06, 28 December 2005 (UTC)

- Oh man, I didn't even see that reference at the bottom. I apologize. Kwami's corrections are correct as far as the Bulgarian postalveolars not being Russian, but considering that most readers of the page will be unfamiliar with the minute details of Russian phonetics and the Russian phonemes chart has a different symbol for its postalveolar sound anyway, it seems unnecessary, especially in a table. I also think that since the page that is linked to is called "postalveolar" and the official IPA chart labels those sounds postalveolar that it's best to keep it simple and call these sounds "postalveolar" here as well.

- Both Russian and Bulgarian postalveolars are often transcribed with the same symbols. There have been some recent reversions on the Russian article to ʃ and ʒ, just like Bulgarian. Also, a lot of people coming to the various Slavic language articles will have some knowledge of Russian, and might think that Bulgarian has been similarly mistranscribed. Combine the two, and a heads-up might prove worthwhile. kwami 05:39, 3 January 2006 (UTC)

- You are right, an illistrative vowel chart is very useful. My understanding of how the vowel charts work is that you don't put allophones on it. I suppose we could alter the image and put the allophonic vowels in parenthesis. AEuSoes1 01:50, 28 December 2005 (UTC)

- Usually it's limited to phonemes, but in this case there's obviously not a problem since there are so few phonetic vowels to deal with. The chart is also explained quite clearly in the paragraph right below it. And no matter what, removing a perfectly correct chart altogether is the least constructive solution.

- Peter Isotalo 15:22, 29 December 2005 (UTC)

Gross misinformation

Look: I don't care where you took this chart from, remember well: Bulgarian has six vowels, SIX, SIX, SIX and NOT eight. There are four other allophones (two between a and @ and two between o and u), which appear in unstressed syllables depending on the position of the unstressed syllable to the stressed syllable within a certain word. If you are posting also allophones and not only phonemes (the reasonable question is why you are doing this but we'll deal with this some other time), then the vowel chart should include all ten of them and not only eight with information which is an allophone and which is a phoneme. But you don't know that, do you?

Then we get to another reasonable question: why do you think that you can erase the whole vowel section with the vowel descriptions? Ha?

So: you post a chart which is WRONG and then you erase a section which is RIGHT. What the hell are you doing? I am getting tired of non-experts who read something somewhere and then come and try to wreak havoc on articles which they understand nothing about. A couple of months ago, one user was trying to change the article Bulgaria because he had read that the Bulgarians were descendants of the Shumers. In two words, your edit is pretty much of the same value and worth. For the phonetics section here, I've used the Routledge compendium on Slavic languages (1991) and the newest Bulgarian edition of New Bulgarian - phonetics, grammar and syntax. Please, consult any book on Bulgarian phonetics before you come again with this vowel chart. VMORO 14:09, 31 December 2005 (UTC)

- Nothing has been removed, VMORO. I only summarized the previous information, which is overly verbose at times. And it would be really helpful if you made proper refernces to your sources. You're specifying no authors, no ISBNs and, as far as I can tell, titles that don't exist.

- Peter Isotalo 15:27, 1 January 2006 (UTC)

Please be civil, and stop removing referenced material

VMORO, Wikipedia is a collaborative effort, and edit summaries like "I'll remove whatever I wish" are inappropriate here. So are the slurs against other editors' level of knowledge that I see above. Please review WP:NPA. Please discontinue this unconstructive revert warring and pull in your horns. Wikipedia runs on civility. If I don't see a change I intend to either protect the article or—if you continue to post this intemperately—block you for disruption. Bishonen | talk 14:32, 31 December 2005 (UTC).

- Followup: Well, that was roundly ignored. I have blocked VMORO for 24 hours for unrepentant edit warring and disruption, specifically for this edit summary. Wikipedia runs on civility. Bishonen | talk 06:03, 3 January 2006 (UTC)

So anyway, I looked here [4] and it also verifies that Bulgarian has six vowel phonemes. I suggest that whoever can do so should take the vowel chart that's been made and edit it to either remove the allophones or put them in parenthesis. It is fairly misleading to put eight vowels in a language that has only six, even if there is a detailed paragraph underneath explaining which ones are allophones. AEuSoes1 20:32, 31 December 2005 (UTC)

- Well, why don't you make an effort and contact the creator of the images, Aeusoes? It sure would be a lot more constructive than just removing them or supporting the idea that no vowel chart at all is better than a vowel chart with allophones in it.

- Peter Isotalo 15:27, 1 January 2006 (UTC)

- Okay. I actually stopped removing the chart since I figured it could be edited. But before the chart was put in, the article had a little table to indicate vowels which is certainly not nothing. AEuSoes1 02:05, 2 January 2006 (UTC)

You try to be civil and stop removing referenced material

So, one of the sources, which I've used used is already added, the other one will follow later today when I check the name. So, let's see if you are gonna remove referenced material. As regards who's the author of the article you need to contact - well, that's me, feel free to contact me. VMORO 10:11, 4 January 2006 (UTC)

Expand this article please Balkan Slavic Future tenses Bonaparte talk 08:14, 2 January 2006 (UTC)

- I've deleted it because you just copyvio'd it from Tomić's paper — interesting as it was... - FrancisTyers 17:00, 19 April 2006 (UTC)

Turkish/Ottoman

Just an outsider's 2 cents: I noticed there was a bout of reverting here about a sentence dealing with Turkish/Ottoman, which was in danger of being drawn into an apparently ongoing edit war. I'm not going to comment on the behaviour of the parties involved, but I'd like to point out that I find this addition by User:81.213.83.14 somewhat unfortunate: "the Turkish language, which was the official language of Ottoman empire along with Ottoman language (which was a version of Turkish)." [5] It may be useful in some contexts to distinguish (modern) Turkish proper from Ottoman, but it seems to make little sense to treat the two as if they had been two separate, contemporary forms side by side with each other. "Ottoman" didn't exist "along with" the official language of the Ottoman empire, it surely was that official language? Lukas 14:02, 3 January 2006 (UTC)

Vowel Chart

I am hereby placing the vowel chart on the talk page until it is brought into conformity with the actual state of affairs in the Bulgarian language:

VMORO 10:34, 4 January 2006 (UTC)

- The chart has been taken from the Bulgarian section of the IPA handbook which has been compiled by Elmar Ternes and Tatjana Vladimirova-Buhtz and I've pointed out many times that all the vowels are not meant to indicate phonemes and I've made this very clear in the article as well. The chart was made by IceKarma based on photos of the vowel charts in the handbook taken by me, since I was the one who asked him to do it.

- As for the analysis of 6 phonemes with 4 allophones, which VMORO is insisting on, this is exactly what the info in the handbook says, except that that the allophones of two of the phoneme pairs are identical. This is pretty much the same as what the current info says, except that the current info is a lot more vague.

- The symbols used are really a matter of finer detail on the part of the vowel chart makers. [ə] is quite close to [ɤ] and choosing the latter symbol is much more sensible, since it is a near-back vowel. The same goes for [ɐ], which is also very close to [ə]. Using schwa for both [ɐ] and [ɤ] would be to over-simplify an already quite uncomplicated vowel system.

- Peter Isotalo 15:24, 4 January 2006 (UTC)

- No, it wouldn't be to over-simplify it, cause it's really that simple! Like VMORO, I am a native speaker of Bulgarian. We speak Bulgarian and we know what vowels we pronounce, when we speak. I myself might not be a philologist, but I am very interested in linguistics and, especially, phonetics and I also believe I am a well educated person, who speaks correct Bulgarian (I've been working as a journalist). Considering all this, you shoul not only believe VMORO, but me too, when we tell you that there are 6 vowels in Bulgarian, that is all. It's a nice and simple vowel system, which I am proud of, unlike the awfully complex vowel systems of all Germanic languages.

- Please, don't take that as a personal insult, especially since its not your fault what your language sounds like and you haven't chosen it :) I just don't like it that you people up there North have so many freaking vowels, large groups of which sound like mere variations of one vowel, which we have to twist our mouths and make strange faces in order to pronounce correctly :) (Note that I'm not saying they are not separate vowels, cause I for one know they are, I'm just saying that, to an average Bulgarian, they sound the same). It's all a real mess for any Bulgarian (likewise an Italian or Spaniard, I guess), who tries to learn English, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, etc. But what is worse is that for speakers of those Germanic languages, who don't know linguistics and phonetics, it's equally hard to comprehend the simplicity of our nice 6 vowels, so it always an agony to try and explain to them the pronunciation of even one simple Bulgarian word. I've also had frustrating arguments with friends of mine from New Zealand, who don't believe me, when I tell them their "e" (as in "pet") sounds similar to the "i" (as in "pit") of other English speakers - so, in their NZ accent, the word "pet" e.g. sounds like "pit". They claim it's completely different, believe it or not! This is because they have so many forms of "i", perceived as separate vowels, that they can't comprehend that for us it all sounds like "i", cause we only have one form of it. Of course, all I've said in this paragraph is just my personal opinion - other people may like the diversity of the Germanic phonetic systems more than the simplicity of the ones of Bulgarian, Italian, etc. :)

- Anyway, I digress. The main thing I wanted to say was: please, leave our language alone and don't confuse readers with vowel charts like that one. We don't need such "finer detail on the part of the vowel chart makers", when we don't actually have that detail in the language. There is no need for 2 or 3 symbols for just one vowel, which can simply be represented with the schwa - it's the closed one of the central pair of vowels, the "a" being the open one. It was also awfully hard for me to explain to those same NZ friends of mine how that vowel is pronounced in Bulgarian, which is amazing, considering how often it occurs (though apparently in variations) in English. I would have expected that from native speakers of Italian, Spanish or Russian, where they don't even have that vowel, but I didn't expect it from native English speakers :( The problem is for them there seem to be several different [ə] sounds in English and they are all different from the Bulgarian one. For me they all sound similar to it. Don't get me wrong - I don't deny the existence of the numerous vowels in Germanic languages - I'm just happy we only have six and I don't have to moo like a cow etc., when I speak my language :P And I believe it should be represented in the article exactly that way - i.e. I support keeping the current version of the disputed section or revising the vowel chart before putting it back in there.

Christomir

Christomir

- Anyway, I digress. The main thing I wanted to say was: please, leave our language alone and don't confuse readers with vowel charts like that one. We don't need such "finer detail on the part of the vowel chart makers", when we don't actually have that detail in the language. There is no need for 2 or 3 symbols for just one vowel, which can simply be represented with the schwa - it's the closed one of the central pair of vowels, the "a" being the open one. It was also awfully hard for me to explain to those same NZ friends of mine how that vowel is pronounced in Bulgarian, which is amazing, considering how often it occurs (though apparently in variations) in English. I would have expected that from native speakers of Italian, Spanish or Russian, where they don't even have that vowel, but I didn't expect it from native English speakers :( The problem is for them there seem to be several different [ə] sounds in English and they are all different from the Bulgarian one. For me they all sound similar to it. Don't get me wrong - I don't deny the existence of the numerous vowels in Germanic languages - I'm just happy we only have six and I don't have to moo like a cow etc., when I speak my language :P And I believe it should be represented in the article exactly that way - i.e. I support keeping the current version of the disputed section or revising the vowel chart before putting it back in there.

Christomir: Your conversation with your NZ friends is typical for laypeople. An important concept in linguistic is that of a phoneme. This is what should be depicted in a phonology chart. The vowels in <pit> and <pet> are different phonemes in English (see English phonology. The distinction between phonemes is often difficult for a non-native speaker. On the other hand, there are variations in the pronunciation of phonemes according to the context (called allophones). These variations are mostly done unconsciously and therefore are not perceived by a native speaker, but they are noticed by non-native speakers. The actual pronunciation of phonemes is the subject of the discipline of phonetics. I do not speak or understand Bulgarian, but it appears to me that there are indeed six vowel phonemes in Bulgarian. These phonemes may differ in pronunciation, depending on if they occur in stressed or unstressed position, and on regional variations (see: Accent (linguistics)). A vowel chart as the one at the top of this section cannot accurately represent the phonemes, because each entry consists of an IPA symbol and therefore a specific pronunciation. A better choice would be to have a table with the six phonemes, showing their "standard" pronunciation in stressed and unstressed position. (By "standard" I mean how an educated person would speak in a neutral context, such as a news show in TV). However, because native speakers untrained in linguistic usually do not hear the difference of variants in pronunciation of a phoneme, it is important to consult scientific sources about Bulgarian phonetics. This is mandatory according to Wikipedia guidelines: judging from your own experience as a native speaker would be original research and is not permissible. Andreas 15:51, 13 January 2006 (UTC)

- I never said I thought the vowels in pit and pet in New Zealand English are the same, because I realize that (even in that) they are different phonemes. (In other forms of English they are completely different and almost the same as the Bulgarian "i" and "e".) I just said they sounded similar for us Bulgarians and the New Zealand "e" sounded almost the same as the "i" of non-New Zealand English. But my friend claimed they were completely different, which you have to admit they are not (though I don't know if you people have ever listened to a Kiwi speaking :P). She also claimed that all the [ə]'s in English were different, e.g. the vowel in fur was completely different from the one in stolen. In that case I'm not sure if English phonetics says they are different phonemes or not, but I'm sure for a Bulgarian they sound exactly the same, only one is stressed and the other is not. But, anyway, the subject here is the vowels in Bulgarian, rather than those in English. With all I've been saying I just wanted to show how complicated the vowel system of some languages is and how simple the one of Bulgarian is in comparison. And I'm glad it is :)

Christomir

Christomir

- I don't think that Christomir was providing original research, he was backing up other sources. To my knowledge, I haven't seen any vowel charts that put in unstressed allophones the way the Bulgarian chart has. This vowel chart for Amharic does, but indicates the allophones the way I mentioned before, with parenthesese. I contacted IceKarma but he doesn't seem to be responding and I don't know how to upload pictures. AEuSoes1 18:16, 13 January 2006 (UTC)

- Bulgarian has six vowel phonemes. No has questioned this even once, but I'm glad we've cleared it up once and for all.

- There is a problem here, though. There is no such thing as "standard pronunciation" of any IPA vowel. IPA symbols technically represent cardinal vowels, which are theoretical entities. There are languages that have vowel position which match the theoretical cardinal positions almost exactly, but these are mostly exceptions. Using typed characters for symbols is very ambiguous, and much more prone to dispute, since any vowel that happens to be between two cardinal positions could very well be argued to be either symbol. For example, [u] and [o] or [y] and [ø], or in this case [ɐ] and [ɤ]. Both could very well be interpreted as [ə], which is entirely unsatisfactory. For this reason a table is actually a rather poor alternative to a chart, and for other reasons as well. Displaying IPA as text is not possible on all computers. A vowel chart in the form of an image solves this problem universally and provides some reference when comparing to other languages. I'd also like to point out that the vowel chart depicts an educated form from of Standard Bulgarian, not some exotic rural dialect.

- As for the issue of native speakers having some sort of last say over "their own" language article, I can only echo Andreas comments and point out that being a native speaker doesn't qualify you in the least to be a competent analyst of your own language. Native speaker input is always welcome and will often lead to great articles, but under no circumstances does it trump the contributions of non-natives.

- Since I have consulted the source on Bulgarian phonology provided by VMORO without finding anything that actually contradicts the vowel chart I will reinsert the chart in the article with the appropriate comments. If anyone feels like removing it again, please accompany the removal with a detailed explanation as to why you feel it is wrong (the focus should be on "why" not "it is wrong") and why you feel entitled to reject the IPA handbook as a reliable source; i.e. violate Wikipedia:Verifiability. I'm going to stress the importance of factual argumentation, because merely expressing an editorial opinion about the accuracy of a phonological fact is no more relevant than expressing an opinion about the density of chlorine or the coronation of Queen Victoria.

- And please just drop the parenthasis quibble for now. I'm sure it'll be a great vowel chart once we get them in there, but removing it just because of a subjective triviality is pedantic beyond reason.

- Peter Isotalo 19:56, 13 January 2006 (UTC)

- Just for the record: the Amharic page has a chart and a table. No explanations are given there of what the parentheses stand for. Andreas 20:49, 13 January 2006 (UTC)

Here you go: Andreas 21:36, 13 January 2006 (UTC) File:Bulgarian vowel chart mod.png

- Ahh, I am grateful! Thank you Ανδρέας. And Peter, I never removed the vowel chart because it didn't have parenthesis, I restored the table because at the time I felt that the vowel chart was incorrect. Two weeks ago. Before we even began this discussion. If you want to keep bringing that up, I'll bring up the time you neglected to rinse off your plate and just left it in the sink!!

- I took out the X-Sampa stuff since that's mainly for situations when you can't put in IPA and we can. I also put in "lexicon" as an alternative to "word-stock" but only once. It gives it a little bit of flavor. mmm, tasty! AEuSoes1 03:05, 14 January 2006 (UTC)

We have still to decide which IPA symbol to use for the schwa. Andreas 03:50, 14 January 2006 (UTC)

I'd suggest going with whatever the conventional literature says. It can always be one of those, they-say-it's-this-but-it's-really-that kinds of things like using wedge in RP. AEuSoes1 04:08, 14 January 2006 (UTC)

- I can't find any discrepancy worth mentioning. The Slavonic Languages uses /a/ for /a/ and /ă/ for /ɤ/ respectively. I didn't have time to read the entire chapter on Bulgarian vowels, so I don't know if it's the source of the schwa. Whatever it is, I feel that using [ɐ] for the mid-central allophone is much more accurate.

- Peter Isotalo 10:14, 14 January 2006 (UTC)

- Hey, I don't speak any "exotic rural dialect"!! I know very well how literary Bulgarian is spoken correctly - I am a journalist, soon to be a TV reporter and, hopefully one day, a TV presenter. I was very good at Bulgarian lessons in school and I can tell you they only teach six vowels. I am also sure they only teach six vowels in Bulgarian Philology at university too, although I've never studied it (you can ask VMORO about that one, I think I saw him saying somewhere that he was a philologist). So who do you think knows Bulgarian better - our scientists or some foreign ones? Have you ever thought that IPA are mere people, not gods and, as such, they are not faultless, so it's possible they might have made a mistake for once? Expressing an opinion about this issue is completely different from expressing an opinion about the density of chlorine or the coronation of Queen Victoria, since those fact are much more popular and widely studied that the issue in subject. Also, the fact that you didn't find anything that actually contradicts the vowel chart in that source on Bulgarian phonology doesn't necessarily mean it isn't there, it only means you weren't able to find it :) Also, I don't believe than any one of us was being a dick, but you might just be one for implying that ;)

Christomir

Christomir

- Hey, I don't speak any "exotic rural dialect"!! I know very well how literary Bulgarian is spoken correctly - I am a journalist, soon to be a TV reporter and, hopefully one day, a TV presenter. I was very good at Bulgarian lessons in school and I can tell you they only teach six vowels. I am also sure they only teach six vowels in Bulgarian Philology at university too, although I've never studied it (you can ask VMORO about that one, I think I saw him saying somewhere that he was a philologist). So who do you think knows Bulgarian better - our scientists or some foreign ones? Have you ever thought that IPA are mere people, not gods and, as such, they are not faultless, so it's possible they might have made a mistake for once? Expressing an opinion about this issue is completely different from expressing an opinion about the density of chlorine or the coronation of Queen Victoria, since those fact are much more popular and widely studied that the issue in subject. Also, the fact that you didn't find anything that actually contradicts the vowel chart in that source on Bulgarian phonology doesn't necessarily mean it isn't there, it only means you weren't able to find it :) Also, I don't believe than any one of us was being a dick, but you might just be one for implying that ;)

- If there is any evidence of contradiction in the sources, you're welcome to point it out. Otherwise, I find it ironic that you praise "your" scientists compared to "some foreign ones", because the source presented by me (the IPA handbook) was written by two Bulgarians while the source presented by VMORO (The Slavonic languages) seems to have been written by a native English-speaker. Not that this actually matters, though, since a trained phonetician can be adept at analyzing almost any language. Of course it helps to be a native speaker, but only with the proper education and training.

- Peter Isotalo 09:05, 15 January 2006 (UTC)

- When I said "Bulgarian scientists", I wasn't thinking about the sources - I was talking about the people, who decide what is taught in Bulgaria. Are you trying to convince me that all students in Bulgaria are intentionally taught wrong? Or maybe the scientists who write the textbooks etc. are just stupid?

OK, I'll stop arguing here, since I don't want to be a pest. I'll just assume that I am uneducated and untrained. Christomir

Christomir

- When I said "Bulgarian scientists", I wasn't thinking about the sources - I was talking about the people, who decide what is taught in Bulgaria. Are you trying to convince me that all students in Bulgaria are intentionally taught wrong? Or maybe the scientists who write the textbooks etc. are just stupid?

- Few, if any, countries teach advanced phonology of their own language to students unless they actually take a course in linguistics on a university level. There's simply no need for it because native speakers know how to speak their language properly anyway and have it internalized without having to be taught things like phonetics theoretically. Things like orthography and diction are what's focused on. (Illiterate people can speak a language fluently without a single day of schooling.) But ask any average student of any country about the finer points of the phonology of their own language and I can tell you that most of them will get most of it wrong. They'll pronounce it perfectly, but won't be able to explain most of it on a theoretical level. So, naturally, this is by no means unique to Bulgaria.

- Peter Isotalo 15:59, 16 January 2006 (UTC)

Excuse me. I'm a native speaker and to me this vowel chart seems wrong. I can't really say how many allophones any of the vowels has but what I disagree with is that the phoneme for the "а" sound is shown as more front than the phoneme for the "ъ" sound. However, they actually stand on the same line regarding frontness/backness - the position of the tongue regarding frontness/backness is the same, just the "а" is more open. In fact, the vowel chart which has been provided for Amharic represents much better the relation of the two vowels in Bulgarian - as there they are on the same frontness/backness line! How can I prove it? Well... First of all, I have observed it while pronouncing the two vowels - but I realize that no one can check that. I also have a book - "Modern Bulgarian Language", which says that the place of articulation of "а" and "ъ" is the same. But it looks like it has not been put online so I can't show it to you as evidence... Still, I hope you'll consider what I have written!

- Well the chart has been made from an actual speaker. Every language has its dialects. In my dialect of English, /e/ is actually higher than /ɪ/AEuSoes1 22:13, 11 February 2006 (UTC)

- Anonymous user, if you read the discussions about vowels that have been going on on this talkpage, you'll find all the answers to your questions. If you have a source that claims that two vowels that are considered separate phonemes have the same place of articulation, then you've either misread your source or it's quite obviously incorrect, since all other sources are in agreement on this. Quite a few have been cited so far.

- Peter Isotalo 00:07, 13 February 2006 (UTC)

- Thank you for your answers. However, I'm afraid I don't see why two vowels that are considered separate phonemes can't have the same place of articulation. For example, "o" and "u" - their place of articulation is the same, the only difference is that "o" is more open than "u". Maybe it will be best if I try to translate the part of the Phonetics section from the "Modern Bulgarian Language" which deals with the opposition between "а" and "ъ". Here it is:

- "According to the width of the passage between the most raised part of the tongue and the palate the vowels are divided into narrow and wide. During the articulation of the wide vowels (е, а, о) the space between the tongue and the palate is wide while during the articulation of the narrow (и, ъ, у) the passage is narrower.

- To each wide vowel corresponds one narrow, WHICH HAS THE SAME PLACE OF ARTICULATION but with a lower position of the tongue: (е-и, а-ъ, о-у)."

- I must admit there is a mistake in this text - the narrow vowels should have a "higher" and not a "lower" position of the tongue but I'm sure this is a case of oversight. Furthermore, later in the book an articulation chart of the vowels is given and there the narrow vowels are represented as higher than the wide ones. But what I wanted to show is that according to "Modern Bulgarian Language" the vowels "а" and "ъ" have the same place of articulation, the only difference is that "а" is more open than "ъ". This, combined with the fact that I notice the same when I pronounce "а" and "ъ" (from "а" I just raise my lower jaw to produce "ъ"; I don't move the tongue backwards) makes me come to the conclusion that in Bulgarian "ъ" is not a more back vowel than "а" - instead, they are at the same place according to frontness/backness. That's why I think the vowel chart in the "Bulgarian language" article is wrong.

- About the dialects - I know that some Bulgarian dialects reduce "е" to "и" but I haven't heard of dialectal variation of the frontness/backness of "ъ"... But even if there are some people who pronounce "ъ" a little more back than "а", what is most important is that for Bulgarian speakers the DEFINING feature of "ъ" is that it is the closed counterpart of "а". That's what Bulgarians are taught at school from an early age. And since in the Bulgarian speakers' conscience "ъ" is the closed counterpart of "а", it would be logical that they would pronounce the two vowels at one and the same place (regarding frontness/backness)... or at least very close to each other. And I think that should be represented in the vowel chart.

It's strange that Tilkov and Boyadzhiev have used the term "place of articulation" to refer to the frontness/backness continuum, but NOT to vowel height. It doesn't make much sense to me. Furthermore, when we studied linguistics, the distinction "place of articulation" vs "active organ of articulation" wasn't used for vowels at all, it was only for consonants. That is confirmed by the present articles on "place of articulation" and "vowel" in Wikipedia, as well as by my textbook in linguistics from 1965.

I must admit that I, too, have problems imagining "a" being THAT front. But the fact that we native speakers aren't conscious of that doesn't mean that it isn't true: we don't learn our Bulgarian phonetics at school. Look, if you find another vowel chart for Bulgarian, and one that comes from a source as authoritative as the present one, then replacing the present chart might become an option. --85.187.44.128 14:17, 19 March 2006 (UTC)

- Let us replace /a/ with /ɑ/? According to the so-called 'academic grammar' i.e. the three volume grammar on Bulgarian syntax, phonology and morphology, published by the BG Academy of Sciences, it is a back vowel, more precisely an open back unrounded vowel, to quote them precisely „Артикулационните характеристики определят гласната [a] по следния начин: по учленително място тя е задна, по степен на издигане на езика — ниска, а по проход между гърба на езика и небцето — широка” (In not the best translation: 'The articulatory characteristics define the vowel [a] in the following way: according to its place of articulation as back, by the vertical position of the tongue — low, and by the opening between the blade of the tongue and the palate — wide'). Also according to Vladimir Zhobov its IPA representation should be with /ɑ̟/ (/ɑ/ with a plus-like sign under it) indicating, I believe, it's advanced, same for ɤ actually i.e. /ɤ̟/. However he later states that both а and ъ are more central („по-скоро централни” as he puts it) and on his chart vertically they're in the same position, I believe according to him they'd be classified as open near-back unrounded vowel and close-mid near-back unrounded vowel respectively. At any rate they all agree it's more back than front, ok the table does put it in the 'Central' column, but the IPA symbol is of a front vowel and the chart is plain wrong.

Hi all, I've created a vectorized Bulgarian vowel chart that may be more conducive to editing/debating/tweaking. ǝɹʎℲxoɯ (contrib) 03:59, 19 February 2009 (UTC)

Terminology quibbles

Hey, Peter and VMORO, if you two go on fighting over "lexis", "word stock" and "vocabulary", or "writing system" vs. "alphabet", or "sound system", or whatnot, you risk nomination for "lamest edit war of the year", and the year has only just started. Take a break, you two! ;-) (By the way, I personally find all these expressions perfectly acceptable, and if you really can't agree, I offer to be the arbiter and decide on the authority of my own whims.) Lukas 16:59, 8 January 2006 (UTC)

RfC comments

I have skimmed the more recent edits and recommend that:

- Peter and especially VMORO start taking each other's knowledge and insights more seriously, which should enable them to reach consensus on more complex issues like the vowel chart dispute. Reread WP:NPOV and WP:NOR. If you can't reach consensus -- take a break, as Lukas said.

- simple differences of opinion about usage (with references for both points of view) be left for other editors to decide. Especially where both proposed terms are generic words as opposed to linguistic terminology. Take a break.

If I may suggest some pointers:

- A possible consensus on the vowel chart issue -- is it feasible to put both approaches in, possibly indicating (based on references to reputable sources) their relative importance, various uses, etc.?

- A distinction can sometimes be made between two versions of the same language: the "cultural language" and the "spoken language" (colloquial language/vernacular). Perhaps this helps you resolve the Ottoman vs. Turkish problem. I think the current wording (I'm not sure if it already reflects a consensus) needs to be improved.

- When two terms are proposed for the same concept, it can be helpful if both terms are given, one of them in parentheses.

Perhaps I will give some examples by editing the article myself (feel free to revert if you don't agree). But even when you have reached a version everyone agrees on, you shouldn't be surprised when someone else comes along and edits it into something you wish you had written but didn't think of. I am not commenting on any WP:CIV, WP:NPA, etc. issues since this is an Article RfC, not a User Conduct RfC. By the way, is the Terminology Quibbles section a response to the RfC? If so, you may want to move it into the RfC Comments section. I hope this helps. AvB ÷ talk 10:19, 10 January 2006 (UTC)

- The Turkish/Ottoman thang is not my quibble. I'm simply trying to include info on phonology I believe is relevant and to copyedit the article into good, reasonably uncomplicated English. I've also tried arguing facts concenring the vowel chart already. I'm still waiting for VMORO to return the favor.

- Peter Isotalo 15:06, 10 January 2006 (UTC)

- I hope you'll get more comments from others. Once again, you would both do well to reread policies such as WP:NPOV, WP:NOR and WP:NPA from top to bottom, even if you think you know them by heart. Then try to work things out in good faith -- or take that break. This advice is meant for the both of you but VMORO needs it the most I'm afraid. I hope to see you reach consensus. Much more rewarding than ending up with warnings and one or more user blocks. AvB ÷ talk 16:57, 11 January 2006 (UTC)

Sources

- When unstressed both a and ъ are pronounced the same way - somewhere between a and ъ - like u in but.

- When unstressed both o and у are pronounced somewhere between о and y.

Bulgarian is a language which, like a number of Slavic languages, disprefers unstressed mid vowels. The degree to which unstressed mid vowels are disliked varies from dialect to dialect, as do the strategies used to avoid them. In most dialects of Bulgarian (including the standard dialect), unstressed mid vowels are raised: o become u, and e becomes i. [7]

The maximum number of vowel phonemes (6) is only met in stressed position, while in unstressed position this number is smaller. In the pairs /a - з/ and /o - u/, the distinction “close - open” is neutralised and the actual realisation depends on the position of the respective vowel relative to the position of lexical acccent in the word. In the pair / e - i / the close - open opposition, while still functional in minimal pairs such as векове /veko’ve/ (ages) - викове /viko’ve/ (cries - noun, pl.), also shows a tendency towards neutralisation (Tilkov and Boyadzhiev 1990:63-4) [8]

The phonetic realization of stress is rather language-specific. Trubetzkoy (1939) pointed out that in Bulgarian the contrast between close /u/ and mid // found in stressed syllables is neutralized in unstressed syllables, where only /u/ - the closer phoneme - occurs. [9]

/a/ and /ɤ/ are neutralised to [ɐ] in unstressed positions: ритам 'I kick'—ритъм 'rhythm' [ˈritɐm]. Similarly, [o] is the unstressed neutralisation of /ɔ/ and /u/: оказвам 'I exert, render' —указвам 'I indicate' [oˈкazvɐm]. [10]

Results of a spectral analysis of vowel reduction in Bulgarian (N = 2 educated male speakers of the Sofia dialect) & model experiments that test these results are reported. The hypothesis was that reduction of Bulgarian open vowels is related to neutralization of mandibular depression, weakening or elimination of lingual & labial compensation for mandibular errors, & weakening of pharyngeal narrowing: models were developed to match spectral regression for pharyngeal /a/, palatal /e/, & pharyngovelar /o/. The experiments indicate that reduction is gradual rather than discrete, suggesting that an underlying articulatory plan for a complete rendering is executed with varying degrees of attention, depending on which components are neutralized & how far. The articulatory behavior modeled in the experiments successfully reproduced the observed spectral reduction. Results demonstrate that the reduction of Bulgarian /e, a, o/ in unstressed syllables can be explained in terms of partial or complete neutralization of mandibular depression, lip spreading or rounding, pharyngeal activity, & compensation. [11]

As evidence for this statement, note that while all six vowels may occur in stressed syllables, only /i/, /e/, // and /u/ occur in unstressed syllables [12]

In a language like Bulgarian, /a/ reduces to schwa (neutralising with a phonemic schwa which does not undergo reduction by raising) and /e/ and /o/ reduce to /i/ and /u/ respectively. [13] Andreas 17:29, 14 January 2006 (UTC)

Anderson, J. 1996. The representation of vowel reduction: Non-specification and reduction in Old English and Bulgarian. STUDIA LINGUISTICA 50 (2): 91-105.

WOOD, SAJ; PETTERSSON, T. 1988. VOWEL REDUCTION IN BULGARIAN - THE PHONETIC DATA AND MODEL EXPERIMENTS. FOLIA LINGUISTICA 22 (3-4): 239-262.

PETTERSSON, T; WOOD, S. 1987. VOWEL REDUCTION IN BULGARIAN AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR THEORIES OF VOWEL PRODUCTION - A REVIEW OFTHE PROBLEM. FOLIA LINGUISTICA 21 (2-4): 261-279.

TOOPS, G. 1986. VOCATIVE FORMS AND VOWEL REDUCTION IN BULGARIAN. WELT DER SLAVEN-HALBJAHRESSCHRIFT FUR SLAVISTIK 31 (2): 324-335. Andreas 18:25, 14 January 2006 (UTC)

Recall from section 2.3.2.1. that other languages, such as Bulgarian, show a slightly different pattern of vowel distribution in strong vs. weak syllables. Like Dutch, Bulgarian shows the full range of vowel contrasts in stressed syllables, but in unstressed syllables vowels do not reduce to schwa, but to a subset of the vowels in Bulgarian. Pettersson & Wood (1987:266) claim that the vowels in Bulgarian have the following distribution in stressed vs. unstressed positions: (54)

| stressed | unstressed | |

|---|---|---|

| /i/ | [i] | [i] |

| /e/ | [e], [ɛ] | [i] |

| /u/ | [u] | [u] |

| /o/ | [o], [ɔ], | [u] |

| /ă/ | [ɐ], [ ɜ]. [ɘ ] | [ɐ] |

| /a/ | [a] | [ɐ] |

The difference in vowel distribution in stressed vs. unstressed syllables is accounted for by referring to the licensing relations that hold between these positions (Harris 1997). Prosodic words are typically subdivided into feet, and a foot typically contains two syllables, a strong and a weak one. The strong, or stressed, syllable licenses the weak, or unstressed, syllable in a foot. This dependency relation suggests that restrictions are imposed on the unstressed nucleus by the stressed nucleus. In Bulgarian this is evidenced by the fact that the unstressed nucleus has to contain a vowel that consists of a subset of the elements that makes up the corresponding vowel in stressed position. [14] [15]Andreas 19:36, 14 January 2006 (UTC)

Hungary

According to Hungary as well as Demographics of Hungary, there is no sizable population of Bulgarian-speakers in Hungary. Alexander 007 22:18, 31 January 2006 (UTC)

- Bulgarians cites 3,000 Bulgarians in Hungary. Is that enough to mention Hungary? Alexander 007 22:21, 31 January 2006 (UTC)

- There are more Swedish speakers in London than that, but I certainly wouldn't mention it in the (Swedish language) infobox. I'm removing Hungary and shortening the part about Bulgarian diasporas. I'm tempted to remove Macedonia as well, not because I want to take sides in the Bulgarian/Macedonian conflict, but because it's likely to be far fewer than is justified for the infobox. I suggest that you take up (relevant) minority speaker populations up under the header "Geographic distribution".

- Peter Isotalo 20:47, 4 February 2006 (UTC)

There are some 1000 Yiddish speakers in Sweden, however this doesn't stop the Swedes from giving it a 'minority language' status.

Sources about Bulgarian in R. Macedonia

I suggest FunkyFly and other users to point out sources about their thesis that Bulgarian is spoken in Macedonia. Many relevant and neutral sources state that Bulgarian isn't spoken in Macedonia, as for example: