TGF beta receptor 1

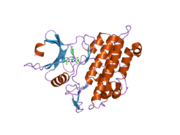

Transforming growth factor beta receptor I (activin A receptor type II-like kinase, 53kDa) is a membrane-bound TGF beta receptor protein of the TGF-beta receptor family for the TGF beta superfamily of signaling ligands. TGFBR1 is its human gene.

Function

[edit]The protein encoded by this gene forms a heteromeric complex with type II TGF-β receptors when bound to TGF-β, transducing the TGF-β signal from the cell surface to the cytoplasm. The encoded protein is a serine/threonine protein kinase. Mutations in this gene have been associated with Loeys–Dietz aortic aneurysm syndrome (LDS, LDAS).[5]

Interactions

[edit]TGF beta receptor 1 has been shown to interact with:

Inhibitors

[edit]- GW-788,388

- LY-2109761

- Galunisertib (LY-2157299)

- SB-431,542

- SB-525,334

- RepSox[24]

Animal studies

[edit]Defects are observed when the TGFBR-1 gene is either knocked-out or when a constitutively active TGFBR-1 mutant (that is active in the presence or absence of ligand) is knocked-in.

In mouse TGFBR-1 knock-out models, the female mice were sterile. They developed oviductal diverticula and defective uterine smooth muscle, meaning that uterine smooth muscle layers were poorly formed. Oviductal diverticula are small, bulging pouches located on the oviduct, which is the tube that transports the ovum from the ovary to the uterus. This deformity of the oviduct occurred bilaterally and resulted in impaired embryo development and impaired transit of the embryos to the uterus. Ovulation and fertilization still occurred in the knock-outs, however remnants of embryos were found in these oviductal diverticula.[25]

In mouse TGFBR-1 knock-in models where a constitutively active TGFBR-1 gene is conditionally induced, the over-activation of the TGFBR-1 receptors lead to infertility, a reduction in the number of uterine glands, and hypermuscled uteri (an increased amount of smooth muscle in the uteri).[26]

Research into how turning off the TGFBR-1 gene affects spinal cord development in mice led to the discovery that, when the gene is turned off, external genitalia instead form as two hind legs.[27]

These experiments show that the TGFB-1 receptor plays a critical role in the function of the female reproductive tract. They also show that genetic mutations in the TGFBR-1 gene may lead to fertility issues in women.

References

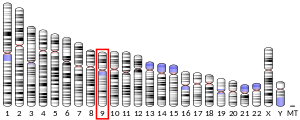

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000106799 – Ensembl, May 2017

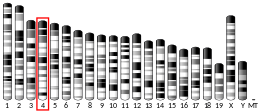

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000007613 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: TGFBR1 transforming growth factor, beta receptor I (activin A receptor type II-like kinase, 53kDa)".

- ^ a b Razani B, Zhang XL, Bitzer M, von Gersdorff G, Böttinger EP, Lisanti MP (March 2001). "Caveolin-1 regulates transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta/SMAD signaling through an interaction with the TGF-beta type I receptor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (9): 6727–38. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008340200. PMID 11102446.

- ^ Guerrero-Esteo M, Sanchez-Elsner T, Letamendia A, Bernabeu C (August 2002). "Extracellular and cytoplasmic domains of endoglin interact with the transforming growth factor-beta receptors I and II". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (32): 29197–209. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111991200. hdl:10261/167807. PMID 12015308.

- ^ Barbara NP, Wrana JL, Letarte M (January 1999). "Endoglin is an accessory protein that interacts with the signaling receptor complex of multiple members of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (2): 584–94. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.2.584. PMID 9872992.

- ^ Wang T, Donahoe PK, Zervos AS (July 1994). "Specific interaction of type I receptors of the TGF-beta family with the immunophilin FKBP-12". Science. 265 (5172): 674–6. Bibcode:1994Sci...265..674W. doi:10.1126/science.7518616. PMID 7518616.

- ^ Liu F, Ventura F, Doody J, Massagué J (July 1995). "Human type II receptor for bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs): extension of the two-kinase receptor model to the BMPs". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 15 (7): 3479–86. doi:10.1128/mcb.15.7.3479. PMC 230584. PMID 7791754.

- ^ Kawabata M, Imamura T, Miyazono K, Engel ME, Moses HL (December 1995). "Interaction of the transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor with farnesyl-protein transferase-alpha". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (50): 29628–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.50.29628. PMID 8530343.

- ^ Wrighton KH, Lin X, Feng XH (July 2008). "Critical regulation of TGFbeta signaling by Hsp90". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (27): 9244–9. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800163105. PMC 2453700. PMID 18591668.

- ^ Mochizuki T, Miyazaki H, Hara T, Furuya T, Imamura T, Watabe T, Miyazono K (July 2004). "Roles for the MH2 domain of Smad7 in the specific inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (30): 31568–74. doi:10.1074/jbc.M313977200. PMID 15148321.

- ^ Asano Y, Ihn H, Yamane K, Kubo M, Tamaki K (January 2004). "Impaired Smad7-Smurf-mediated negative regulation of TGF-beta signaling in scleroderma fibroblasts". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 113 (2): 253–64. doi:10.1172/JCI16269. PMC 310747. PMID 14722617.

- ^ Koinuma D, Shinozaki M, Komuro A, Goto K, Saitoh M, Hanyu A, Ebina M, Nukiwa T, Miyazawa K, Imamura T, Miyazono K (December 2003). "Arkadia amplifies TGF-beta superfamily signalling through degradation of Smad7". The EMBO Journal. 22 (24): 6458–70. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg632. PMC 291827. PMID 14657019.

- ^ Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Causing CG, Bonni S, Zhu H, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL (December 2000). "Smad7 binds to Smurf2 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the TGF beta receptor for degradation". Molecular Cell. 6 (6): 1365–75. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00134-9. PMID 11163210.

- ^ Hayashi H, Abdollah S, Qiu Y, Cai J, Xu YY, Grinnell BW, Richardson MA, Topper JN, Gimbrone MA, Wrana JL, Falb D (June 1997). "The MAD-related protein Smad7 associates with the TGFbeta receptor and functions as an antagonist of TGFbeta signaling". Cell. 89 (7): 1165–73. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80303-7. PMID 9215638. S2CID 16552782.

- ^ a b Datta PK, Moses HL (May 2000). "STRAP and Smad7 synergize in the inhibition of transforming growth factor beta signaling". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 20 (9): 3157–67. doi:10.1128/mcb.20.9.3157-3167.2000. PMC 85610. PMID 10757800.

- ^ Griswold-Prenner I, Kamibayashi C, Maruoka EM, Mumby MC, Derynck R (November 1998). "Physical and functional interactions between type I transforming growth factor beta receptors and Balpha, a WD-40 repeat subunit of phosphatase 2A". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 18 (11): 6595–604. doi:10.1128/mcb.18.11.6595. PMC 109244. PMID 9774674.

- ^ Datta PK, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Moses HL (December 1998). "Identification of STRAP, a novel WD domain protein in transforming growth factor-beta signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (52): 34671–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.52.34671. PMID 9856985.

- ^ Ebner R, Chen RH, Lawler S, Zioncheck T, Derynck R (November 1993). "Determination of type I receptor specificity by the type II receptors for TGF-beta or activin". Science. 262 (5135): 900–2. Bibcode:1993Sci...262..900E. doi:10.1126/science.8235612. PMID 8235612.

- ^ Oh SP, Seki T, Goss KA, Imamura T, Yi Y, Donahoe PK, Li L, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P, Kim S, Li E (March 2000). "Activin receptor-like kinase 1 modulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling in the regulation of angiogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (6): 2626–31. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.2626O. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.6.2626. PMC 15979. PMID 10716993.

- ^ Kawabata M, Chytil A, Moses HL (March 1995). "Cloning of a novel type II serine/threonine kinase receptor through interaction with the type I transforming growth factor-beta receptor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (10): 5625–30. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.10.5625. PMID 7890683.

- ^ Mishra, Tarun; Bhardwaj, Vipin; Ahuja, Neha; Gadgil, Pallavi; Ramdas, Pavitra; Shukla, Sanjeev; Chande, Ajit (June 2022). "Improved loss-of-function CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in human cells concomitant with inhibition of TGF-β signaling". Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids. 28: 202–218. doi:10.1016/j.omtn.2022.03.003. PMC 8961078. PMID 35402072. S2CID 247355285.

- ^ Li Q, Agno JE, Edson MA, Nagaraja AK, Nagashima T, Matzuk MM (October 2011). "Transforming growth factor β receptor type 1 is essential for female reproductive tract integrity and function". PLOS Genetics. 7 (10): e1002320. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002320. PMC 3197682. PMID 22028666.

- ^ Gao Y, Duran S, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Burghardt RC, Bayless KJ, Bartholin L, Li Q (February 2015). "Constitutive activation of transforming growth factor Beta receptor 1 in the mouse uterus impairs uterine morphology and function". Biology of Reproduction. 92 (2): 34. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.114.125146. PMC 4435420. PMID 25505200.

- ^ Reardon, Sara (2024-03-28). "Scientists made a six-legged mouse embryo — here's why". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-00943-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Massagué J (June 1992). "Receptors for the TGF-beta family". Cell. 69 (7): 1067–70. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90627-O. PMID 1319842. S2CID 54268875.

- Wrana JL (1998). "TGF-beta receptors and signalling mechanisms". Mineral and Electrolyte Metabolism. 24 (2–3): 120–30. doi:10.1159/000057359. PMID 9525694. S2CID 84458561.

- Josso N, di Clemente N, Gouédard L (June 2001). "Anti-Müllerian hormone and its receptors". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 179 (1–2): 25–32. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00467-1. PMID 11420127. S2CID 27316217.