Symptoms of COVID-19

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

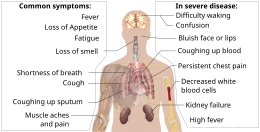

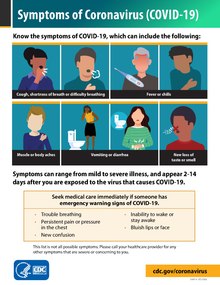

The symptoms of COVID-19 are variable depending on the type of variant contracted, ranging from mild symptoms to a potentially fatal illness.[1][2] Common symptoms include coughing, fever, loss of smell (anosmia) and taste (ageusia), with less common ones including headaches, nasal congestion and runny nose, muscle pain, sore throat, diarrhea, eye irritation,[3] and toes swelling or turning purple,[4] and in moderate to severe cases, breathing difficulties.[5] People with the COVID-19 infection may have different symptoms, and their symptoms may change over time.

Three common clusters of symptoms have been identified: a respiratory symptom cluster with cough, sputum, shortness of breath, and fever; a musculoskeletal symptom cluster with muscle and joint pain, headache, and fatigue; and a cluster of digestive symptoms with abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea.[5] In people without prior ear, nose, or throat disorders, loss of taste combined with loss of smell is associated with COVID-19 and is reported in as many as 88% of symptomatic cases.[6][7][8]

Published data on the neuropathological changes related with COVID-19 have been limited and contentious, with neuropathological descriptions ranging from moderate to severe hemorrhagic and hypoxia phenotypes, thrombotic consequences, changes in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM-type), encephalitis and meningitis. Many COVID-19 patients with co-morbidities have hypoxia and have been in intensive care for varying lengths of time, confounding interpretation of the data.[9]

Of people who show symptoms, 81% develop only mild to moderate symptoms (up to mild pneumonia), while 14% develop severe symptoms (dyspnea, hypoxia, or more than 50% lung involvement on imaging) that require hospitalization, and 5% of patients develop critical symptoms (respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiorgan dysfunction) requiring ICU admission.[10][needs update]

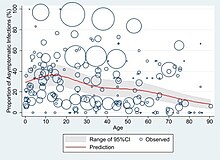

At least a third of the people who are infected with the virus do not develop noticeable symptoms at any point in time.[11][12][13] These asymptomatic carriers tend not to get tested and can still spread the disease.[13][14][15][16] Other infected people will develop symptoms later (called "pre-symptomatic") or have very mild symptoms and can also spread the virus.[16]

As is common with infections, there is a delay, or incubation period, between the moment a person first becomes infected and the appearance of the first symptoms. The median delay for COVID-19 is four to five days[17] possibly being infectious on 1–4 of those days.[18] Most symptomatic people experience symptoms within two to seven days after exposure, and almost all will experience at least one symptom within 12 days.[17][19]

Most people recover from the acute phase of the disease. However, some people continue to experience a range of effects, such as fatigue, for months, even after recovery.[20] This is the result of a condition called long COVID, which can be described as a range of persistent symptoms that continue for weeks or months at a time.[21] Long-term damage to organs has also been observed after the onset of COVID-19. Multi-year studies are underway to further investigate the potential long-term effects of the disease.[22]

The Omicron variant became dominant in the U.S. in December 2021. Symptoms with the Omicron variant are less severe than they are with other variants.[23]

Overview

[edit]

Some less common symptoms of COVID-19 can be relatively non-specific; however the most common symptoms are fever, dry cough, and loss of taste and smell.[1][24] Among those who develop symptoms, approximately one in five may become more seriously ill and have difficulty in breathing. Emergency symptoms include difficulty in breathing, persistent chest pain or pressure, sudden confusion, loss of mobility and speech, and bluish face or lips; immediate medical attention is advised if these symptoms are present.[1] Further development of the disease can lead to complications including pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, septic shock, and kidney failure.

Some symptoms usually appear sooner than others, with deterioration usually developing in the second week.[25] In August 2020, scientists at the University of Southern California reported the "likely" order of initial symptoms of the COVID-19 disease as a fever followed by a cough and muscle pain, and that nausea and vomiting usually appear before diarrhea.[26][non-primary source needed] This contrasts with the most common path for influenza where it is common to develop a cough first and fever later.[26] Impaired immunity in part drive disease progression after SARS-CoV-2 infection.[27] While health agency guidelines tend to recommend isolating for 14 days while watching for symptoms to develop,[28] there is limited evidence that symptoms may develop for some patients more than 14 days after initial exposure.[29]

Symptom profile of variants

[edit]The frequency of symptoms predominating for people with different variants may differ from what was observed in the earlier phases of the pandemic.

Delta

[edit]People infected with the Delta variant may mistake the symptoms for a bad cold and not realize they need to isolate. Common symptoms reported as of June 2021 have been headaches, sore throat, runny nose, and fever.[30][medical citation needed][31]

Omicron

[edit]British epidemiologist Tim Spector said in mid-December 2021 that the majority of symptoms of the Omicron variant were the same as a common cold, including headaches, sore throat, runny nose, fatigue and sneezing, so that people with cold symptoms should take a test. "Things like fever, cough and loss of smell are now in the minority of symptoms we are seeing. Most people don't have classic symptoms." People with cold symptoms in London (where Covid was spreading rapidly) are "far more likely" to have Covid than a cold.[32]

A unique reported symptom of the Omicron variant is night sweats,[33] particularly with the BA.5 subvariant.[34] Also, loss of taste and smell seem to be uncommon compared to other strains.[35][36]

Systemic

[edit]Typical systemic symptoms include fatigue, and muscle and joint pains. Some people have a sore throat.[1][2][24]

Fever

[edit]Fever is one of the most common symptoms in COVID-19 patients. However, the absence of the symptom itself at an initial screening does not rule out COVID-19. Fever in the first week of a COVID-19 infection is part of the body's natural immune response; however in severe cases, if the infections develop into a cytokine storm the fever is counterproductive. As of September 2020, little research had focused on relating fever intensity to outcomes.[37]

A June 2020 systematic review reported a 75–81% prevalence of fever.[2] As of July 2020, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported a prevalence rate of ~45% for fever.[5]

Pain

[edit]A June 2020 systematic review reported a 27–35% prevalence of fatigue, 14–19% for muscle pain, 10–14% for sore throat.[2] As of July 2020, the ECDC reported a prevalence rate of ~63% for muscle weakness (asthenia), ~63% for muscle pain (myalgia), and ~53% for sore throat.[5]

Respiratory

[edit]Cough is another typical symptom of COVID-19, which could be either dry or a productive cough.[2]

Some symptoms, such as difficulty breathing, are more common in patients who need hospital care.[1] Shortness of breath tends to develop later in the illness. Persistent anosmia or hyposmia or ageusia or dysgeusia has been documented in 20% of cases for longer than 30 days.[6][7]

Respiratory complications may include pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[38][39][40][41]

As of July 2020, the ECDC reported a prevalence rate of ~68% for nasal obstruction, ~63% for cough, ~60% for rhinorrhoea or runny nose.[5] A June 2020 systematic review reported a 54–61% prevalence of dry cough and 22–28% for productive cough.[2]

Cardiovascular

[edit]Coagulopathy is established to be associated with COVID-19 in those patients in critical state.[43] Thromboembolic events, such as blood clots show with high risk in COVID-19 patients in some studies.[44] The viral papain-like protease (PLpro) is thought to be involved in the coagulopathy.[45] Proteolytic cleavage of PROS1 and VWF by the PLpro has been reported.[46] Other cardiovascular complications may include heart failure, arrhythmias, and heart inflammation.[47][48][49][50][51] They are common traits in severe COVID-19 patients due to the relation with the respiratory system.[52]

Hypertension seems to be the most prevalent risk factor for myocardial injury in COVID-19 disease. It was reported in 58% of individuals with cardiac injury in a recent meta-analysis.[53]

Several cases of acute myocarditis associated with COVID-19 have been described around the globe and are diagnosed in multiple ways. Taking into consideration serology, leukocytosis with neutrophilia and lymphopenia was found in many patients. Cardiac biomarkers troponin and N-terminal (NT)-prohormone BNP (NT-proBNP) were seen elevated. Similarly, the level of inflammation-related markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer, IL-6, procalcitonin was significantly increased, indicating an inflammatory process in the body. Electrocardiogram findings were variable and ranged from sinus tachycardia, ST-segment elevation, T-wave inversion and ST-depression.[54] In one case, viral particles were seen in the interstitial cell, and another case reported SARS-CoV-2 RT–PCR positivity in the cardiac tissue suggestive of direct viral injury to the myocardium.[55][56] Endomyocardial biopsy [EMB] remains the gold standard invasive technique in diagnosing myocarditis; however, due to the increased risk of infection, it is not done in COVID-19 patients.[citation needed]

The binding of the SARS-CoV-2 virus through ACE2 receptors present in heart tissue may be responsible for direct viral injury leading to myocarditis.[54] In a study done during the SARS outbreak, SARS virus RNA was ascertained in the autopsy of heart specimens in 35% of the patients who died due to SARS.[57] It was also observed that an already diseased heart has increased expression of ACE2 receptor contrasted to healthy individuals.[58] Hyperactive immune responses in COVID-19 Patients may lead to the initiation of the cytokine storm. This excess release of cytokines may lead to myocardial injury.[54]

Neurological

[edit]Patients with COVID-19 can present with neurological symptoms that can be broadly divided into central nervous system involvement, such as headache, dizziness, altered mental state, and disorientation, and peripheral nervous system involvement, such as anosmia and dysgeusia.[59] As was noted, COVID-19 has also been linked to various neurological symptoms at the diagnosis or throughout the disease, with over 90% of individuals with COVID-19 having reported at least one subjective neurological symptom.[60] Some patients experience cognitive dysfunction called "COVID fog", or "COVID brain fog", involving memory loss, inattention, poor concentration or disorientation.[61][62] Other neurologic manifestations include seizures, strokes, encephalitis, and Guillain–Barré syndrome (which includes loss of motor functions).[63][64]

As of July 2020, the ECDC reported a prevalence rate of ~70% for headache.[5] A June 2020 systematic review reported a 10–16% prevalence of headache.[2] However, headache could be mistaken for having a random relationship with COVID-19; there is unambiguous evidence that COVID-19 patients who had never had a recurrent headache suddenly get a severe headache daily because of SARS-CoV-2 infection.[60]

Loss of smell

[edit]In about 60% of COVID-19 patients, chemosensory deficit are reported, including losing their sense of smell, either partially or fully.[65][66][67]

This symptom, if it is present at all, often appears early in the illness.[65] Its onset is often reported to be sudden. Smell usually returns to normal within a month. However, for some patients it improves very slowly and is associated with odors being perceived as unpleasant or different from they originally did (parosmia), and for some people smell does not return for at least many months.[66] It is an unusual symptom for other respiratory diseases, so it is used for symptom-based screening.[65][66]

Loss of smell has several consequences. Loss of smell increases foodborne illness due to inability to detect spoiled food, and may increase fire hazards due to inability to detect smoke. It has also been linked to depression. If smell does not return, smell training is a potential option.[66]

It is sometimes the only symptom to be reported, implying that it has a neurological basis separate from nasal congestion. As of January 2021, it is believed that these symptoms are caused by infection of sustentacular cells that support and provide nutrients to sensory neurons in the nose, rather than infection of the neurons themselves. Sustentacular cells have many Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on their surfaces, while olfactory sensory neurons do not. Loss of smell may also be the result of inflammation in the olfactory bulb.[66]

A June 2020 systematic review found a 29–54% prevalence of olfactory dysfunction for people with COVID-19,[65] while an August 2020 study using a smell-identification test reported that 96% of people with COVID-19 had some olfactory dysfunction, and 18% had total smell loss.[66] Another June 2020 systematic review reported a 4–55% prevalence of hyposmia.[2] As of July 2020, the ECDC reported a prevalence rate of ~70% for loss of smell.[5]

A disturbance in smell or taste is more commonly found in younger people, and perhaps because of this, it is correlated with a lower risk of medical complications.[65]

Loss of taste and chemesthesis

[edit]In some people, COVID-19 causes people to temporarily experience changes in how food tastes (dysgeusia or ageusia).[65][66] Changes to chemesthesis, which includes chemically triggered sensations such as spiciness, are also reported. As of January 2021, the mechanism for taste and chemesthesis symptoms were not well understood.[66]

A June 2020 systematic review found a 24–54% prevalence of gustatory dysfunction for people with COVID-19.[65] Another June 2020 systematic review reported a 1–8% prevalence of hypogeusia.[2] As of July 2020, the ECDC reported a prevalence rate of ~54% for gustatory dysfunction.[5]

Other neurological and psychiatric symptoms

[edit]Other neurological symptoms appear to be rare, but may affect half of patients who are hospitalized with severe COVID-19. Some reported symptoms include delirium, stroke, brain hemorrhage, memory loss, psychosis, peripheral nerve damage, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[68] Neurological symptoms in many cases are correlated with damage to the brain's blood supply or encephalitis, which can progress in some cases to acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Strokes have been reported in younger people without conventional risk factors.[69]

As of September 2020, it was unclear whether these symptoms were due to direct infection of brain cells, or of overstimulation of the immune system.[69]

A June 2020 systematic review reported a 6–16% prevalence of vertigo or dizziness, 7–15% for confusion, and 0–2% for ataxia.[2]

Blood clots and bleeding

[edit]Patients are at increased risk of a range of different blood clots, some potentially fatal, for months following COVID infection. The Guardian wrote, "Overall, they [a Swedish medical team] identified a 33-fold increase in the risk of pulmonary embolism, a fivefold increase in the risk of DVT (deep vein thrombosis) and an almost twofold increase in the risk of bleeding in the 30 days after infection. People remained at increased risk of pulmonary embolism for six months after becoming infected, and for two and three months for bleeding and DVT. Although the risks were highest in patients with more severe illness, even those with mild Covid had a threefold increased risk of DVT and a sevenfold increased risk of pulmonary embolism. No increased risk of bleeding was found in those who experienced mild infections." Anne-Marie Fors Connolly at Umeå University said, "If you suddenly find yourself short of breath, and it doesn't pass, [and] you've been infected with the coronavirus, then it might be an idea to seek help, because we find this increased risk for up to six months."[70]

Other

[edit]Other symptoms are less common among people with COVID-19. Some people experience gastrointestinal symptoms such as loss of appetite, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting.[1][71] A June 2020 systematic review reported a 8–12% prevalence of diarrhea, and 3–10% for nausea.[2]

Less common symptoms include chills, coughing out blood, diarrhea, and rash.[24][72] The so-called "COVID toes" are pink to violaceous papules arising on the hands and feet. These chilblain-like lesions often occur only in younger patients and do not appear until late in the disease or during convalescence.[73] Certain genetic polymorphisms (in the TREX1 gene) have been linked to susceptibility towards developing COVID-toe.[74] A June 2020 systematic review reported a 0–1% prevalence of rash in COVID-19 patients.[2]

Approximately 20–30% of people who present with COVID-19 have elevated liver enzymes, reflecting liver injury.[75][76]

Complications include multi-organ failure, septic shock, and death.[38][39][40][41][excessive citations]

Stages of COVID-19 infection

[edit]There are three stages, according to the way COVID-19 infection can be tackled by pharmacological agents, in which the disease can be classified.[77] Stage I is the early infection phase during which the domination of upper respiratory tract symptoms is present. Stage II is the pulmonary phase in which the patient develops pneumonia with all its associated symptoms; this stage is split with Stage IIa which is without hypoxia and Stage IIb which includes hypoxia. Stage III is the hyperinflammation phase, the most severe phase, in which the patient develops acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis and multi-organ failure.[77]

A similar stereotyped course was postulated to be: the first phase of an incubation period, a second phase corresponding to the viral phase, a third phase corresponding to the state of inflammatory pneumonia, a fourth phase corresponding to the brutal clinical aggravation reflected by acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and finally, in survivors, a fifth phase potentially including lung fibrosis, and persisting in the form of "post-covid" symptoms.[78]

Longer-term effects

[edit]Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

[edit]Following the infection, children may develop multisystem inflammatory syndrome, also called paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome. This has symptoms similar to Kawasaki disease, which can possibly be fatal.[79][80][81]

Long COVID

[edit]Around 10% to 30% of non-hospitalised people with COVID-19 go on to develop long COVID. For those that do need hospitalisation, the incidence of long-term effects is over 50%.[82] Long COVID is an often severe multisystem disease with a large set of symptoms. There are likely various, possibly coinciding, causes.[82] Organ damage from the acute infection can explain a part of the symptoms, but long COVID is also observed in people where organ damage seems to be absent.[83]

By a variety of mechanisms, the lungs are the organs most affected in COVID‑19.[84] In people requiring hospital admission, up to 98% of CT scans performed show lung abnormalities after 28 days of illness even if they had clinically improved.[85] People with advanced age, severe disease, prolonged ICU stays, or who smoke are more likely to have long-lasting effects, including pulmonary fibrosis.[86] Overall, approximately one-third of those investigated after four weeks will have findings of pulmonary fibrosis or reduced lung function as measured by DLCO, even in asymptomatic people, but with the suggestion of continuing improvement with the passing of more time.[84] After severe disease, lung function can take anywhere from three months to a year or more to return to previous levels.[87]

The risks of cognitive deficit, dementia, psychotic disorders, and epilepsy or seizures persists at an increased level two years after infection.[88]Post-COVID Condition

[edit]Longer-term effects of COVID-19 have become a prevalent aspect of the disease itself. These symptoms can be referred to as many different names including post-COVID-19 syndrome, long COVID, and long haulers syndrome. An overall definition of post-COVID conditions (PCC) can be described as a range of symptoms that can last for weeks or months.[21] Long COVID can be present in anyone who has contracted COVID-19 at some point; typically, it is more commonly found in those who had severe illness due to the virus.[21][89]

Symptoms

[edit]Long COVID can attack a multitude of organs such as the lungs, heart, blood vessels, kidneys, gut, and brain.[90] Some common symptoms that occur as a result are fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, chest pains, brain fog, gastrointestinal issues, insomnia, anxiety/depression, and delirium.[91] A difference between acute COVID-19 and PCC is the effect that it has on a person's mind. People are found to be dealing with brain fog and impaired memory, and diminished learning ability which has a large impact on their everyday lives.[89][92] A study that took a deeper look into these specific symptoms took 50 SARS-CoV-2 laboratory-positive patients and 50 SARS-CoV-2 laboratory-negative patients to analyze the variety of neurologic symptoms present during long COVID. The most frequent symptoms included brain fog, headache, numbness, dysgeusia (loss of taste), anosmia (loss of smell), and myalgias (muscle pains) with an overall decrease in quality of life.[89]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Symptoms of Coronavirus". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 February 2021. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Grant MC, Geoghegan L, Arbyn M, Mohammed Z, McGuinness L, Clarke EL, et al. (23 June 2020). "The prevalence of symptoms in 24,410 adults infected by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis of 148 studies from 9 countries". PLOS ONE. 15 (6): e0234765. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1534765G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234765. PMC 7310678. PMID 32574165. S2CID 220046286.

- ^ Pardhan S, Vaughan M, Zhang J, Smith L, Chichger H (1 November 2020). "Sore eyes as the most significant ocular symptom experienced by people with COVID-19: a comparison between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 states". BMJ Open Ophthalmology. 5 (1): e000632. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000632. PMC 7705420. PMID 34192153.

- ^ "COVID toes, rashes: How the coronavirus can affect your skin". www.aad.org. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Clinical characteristics of COVID-19". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 10 June 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b Paderno A, Mattavelli D, Rampinelli V, Grammatica A, Raffetti E, Tomasoni M, et al. (December 2020). "Olfactory and Gustatory Outcomes in COVID-19: A Prospective Evaluation in Nonhospitalized Subjects". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 163 (6): 1144–1149. doi:10.1177/0194599820939538. PMC 7331108. PMID 32600175.

- ^ a b Chabot AB, Huntwork MP (September 2021). "Turmeric as a Possible Treatment for COVID-19-Induced Anosmia and Ageusia". Cureus. 13 (9): e17829. doi:10.7759/cureus.17829. PMC 8502749. PMID 34660038.

- ^ Niazkar HR, Zibaee B, Nasimi A, Bahri N (July 2020). "The neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a review article". Neurological Sciences. 41 (7): 1667–1671. doi:10.1007/s10072-020-04486-3. PMC 7262683. PMID 32483687.

- ^ Jafari E, Azizian R, Asareh A, Akrami S, Karimi N (2022). "Comparative study between bacterial meningitis vs. viral meningitis and COVID-19". Infectious Diseases Research. 3 (2): 9. doi:10.53388/IDR20220525009. ISSN 2703-4631.

- ^ "Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 6 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b Wang B, Andraweera P, Elliott S, Mohammed H, Lassi Z, Twigger A, et al. (March 2023). "Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Age: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 42 (3): 232–239. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000003791. PMC 9935239. PMID 36730054.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Oran DP, Topol EJ (May 2021). "The Proportion of SARS-CoV-2 Infections That Are Asymptomatic : A Systematic Review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 174 (5): 655–662. doi:10.7326/M20-6976. PMC 7839426. PMID 33481642.

- "Transmission of COVID-19". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Nogrady B (November 2020). "What the data say about asymptomatic COVID infections". Nature. 587 (7835): 534–535. Bibcode:2020Natur.587..534N. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03141-3. PMID 33214725. S2CID 227079692.

- ^ a b Gao Z, Xu Y, Sun C, Wang X, Guo Y, Qiu S, et al. (February 2021). "A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection = Wei Mian Yu Gan Ran Za Zhi. 54 (1): 12–16. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.001. PMC 7227597. PMID 32425996.

- ^ Oran DP, Topol EJ (September 2020). "Prevalence of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection : A Narrative Review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 173 (5): 362–367. doi:10.7326/M20-3012. PMC 7281624. PMID 32491919.

- ^ Lai CC, Liu YH, Wang CY, Wang YH, Hsueh SC, Yen MY, et al. (June 2020). "Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Facts and myths". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection = Wei Mian Yu Gan Ran Za Zhi. 53 (3): 404–412. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.02.012. PMC 7128959. PMID 32173241.

- ^ a b Furukawa NW, Brooks JT, Sobel J (July 2020). "Evidence Supporting Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 While Presymptomatic or Asymptomatic". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 26 (7). doi:10.3201/eid2607.201595. PMC 7323549. PMID 32364890.

- ^ a b Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C (October 2020). "Mild or Moderate Covid-19". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (18): 1757–1766. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2009249. PMID 32329974.

- ^ Byrne AW, McEvoy D, Collins AB, Hunt K, Casey M, Barber A, et al. (August 2020). "Inferred duration of infectious period of SARS-CoV-2: rapid scoping review and analysis of available evidence for asymptomatic and symptomatic COVID-19 cases". BMJ Open. 10 (8): e039856. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039856. PMC 7409948. PMID 32759252.

- ^ Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC (August 2020). "Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review". JAMA. 324 (8): 782–793. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12839. PMID 32648899. S2CID 220465311.

- ^ "Half of young adults with COVID-19 had persistent symptoms after 6 months". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ a b c CDC (1 September 2022). "Post-COVID Conditions". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ CDC (11 February 2020). "COVID-19 and Your Health". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ CDC (29 March 2022). "Omicron Variant: What You Need to Know". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Coronavirus". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Schulte-Schrepping J, Reusch N, Paclik D, Baßler K, Schlickeiser S, Zhang B, et al. (September 2020). "Severe COVID-19 Is Marked by a Dysregulated Myeloid Cell Compartment". Cell. 182 (6): 1419–1440.e23. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.001. PMC 7405822. PMID 32810438.

- ^ a b Larsen JR, Martin MR, Martin JD, Kuhn P, Hicks JB (13 August 2020). "Modeling the Onset of Symptoms of COVID-19". Frontiers in Public Health. 8: 473. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00473. PMC 7438535. PMID 32903584. S2CID 221105179.

- ^ Zhao F, Ma Q, Yue Q, Chen H (20 April 2022). "SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Lung Regeneration". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 35 (2): e00188–21. doi:10.1128/cmr.00188-21. PMC 8809385. PMID 35107300.

- ^ "Considerations for quarantine of contacts of COVID-19 cases". World Health Organization.

WHO recommends that all contacts of individuals with a confirmed or probable COVID-19 be quarantined in a designated facility or at home for 14 days from their last exposure.

- ^ Bikbov B, Bikbov A (2021). "Maximum incubation period for COVID-19 infection: Do we need to rethink the 14-day quarantine policy?". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 40: 101976. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.101976. PMC 7816956. PMID 33476809.

Notably, these incubation periods longer than 14 days were registered not only in sporadic cases, but in a substantial proportion reaching... 5.0% out of 339, 7.7% out of 104... patients with traced contacts

- ^ Grove N (14 June 2021). "Delta variant Covid symptoms 'include headaches, sore throat and runny nose'". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Roberts M (14 June 2021). "Headache and runny nose linked to Delta variant". BBC News. London. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Devlin H (15 December 2021). "Londoners with cold symptoms more likely to have Covid, says expert". The Guardian.

- ^ Scribner H (21 December 2021). "Doctor reveals new nightly omicron variant symptom". Deseret News. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Quann J (7 July 2022). "Luke O'Neill: Night sweats now a sign of BA.5 COVID variant". Newstalk. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ "Omicron Symptoms: Here's How They Differ From Other Variants". NBC Chicago.

- ^ Slater J (23 January 2022). "Is a change to your taste or smell a sign of Omicron?". Metro.

- ^ Gul MH, Htun ZM, Inayat A (February 2021). "Role of fever and ambient temperature in COVID-19". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 15 (2): 171–173. doi:10.1080/17476348.2020.1816172. PMC 7544962. PMID 32901576.

- ^ a b Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, et al. (February 2020). "The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health - The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 91: 264–266. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. PMC 7128332. PMID 31953166.

- ^ a b Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA (April 2020). "Care for Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19". JAMA. 323 (15): 1499–1500. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3633. PMID 32159735.

- ^ a b Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R (2020). "Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19)". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32150360. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ a b Heymann DL, Shindo N, et al. (WHO Scientific and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards) (February 2020). "COVID-19: what is next for public health?". Lancet. 395 (10224): 542–545. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30374-3. PMC 7138015. PMID 32061313.

- ^ Razaghi A, Szakos A, Al-Shakarji R, Björnstedt M, Szekely L (31 December 2022). "Morphological changes without histological myocarditis in hearts of COVID-19 deceased patients". Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal. 56 (1): 166–173. doi:10.1080/14017431.2022.2085320. ISSN 1401-7431. PMID 35678649. S2CID 249521076.

- ^ Spyropoulos AC, Bonaca MP (January 2022). "Studying the coagulopathy of COVID-19". Lancet. 399 (10320): 118–119. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01906-1. PMC 8598181. PMID 34800425.

- ^ Alnima T, Mulder MM, van Bussel BC, Ten Cate H (2022). "COVID-19 Coagulopathy: From Pathogenesis to Treatment". Acta Haematologica. 145 (3): 282–296. doi:10.1159/000522498. PMC 9059042. PMID 35499460.

- ^ Baroni M, Beltrami S, Schiuma G, Ferraresi P, Rizzo S, Passaro A, et al. (2024). "In Situ Endothelial SARS-CoV-2 Presence and PROS1 Plasma Levels Alteration in SARS-CoV-2-Associated Coagulopathies". Life. 14 (2): 237. doi:10.3390/life14020237. PMC 10890393. PMID 38398746.

- ^ Reynolds ND, Aceves NM, Liu JL, Compton JR, Leary DH, Freitas BT, et al. (2021). "The SARS-CoV-2 SSHHPS Recognized by the Papain-like Protease". ACS Infect Dis. 7 (6): 1483–1502. doi:10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00866. PMC 8171221. PMID 34019767.

- ^ Long B, Brady WJ, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M (July 2020). "Cardiovascular complications in COVID-19". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 38 (7): 1504–1507. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.048. PMC 7165109. PMID 32317203.

- ^ Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, Fahim M, Arendt C, Hoffmann J, et al. (November 2020). "Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". JAMA Cardiology. 5 (11): 1265–1273. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. PMC 7385689. PMID 32730619.

- ^ Lindner D, Fitzek A, Bräuninger H, Aleshcheva G, Edler C, Meissner K, et al. (November 2020). "Association of Cardiac Infection With SARS-CoV-2 in Confirmed COVID-19 Autopsy Cases". JAMA Cardiology. 5 (11): 1281–1285. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3551. PMC 7385672. PMID 32730555.

- ^ Siripanthong B, Nazarian S, Muser D, Deo R, Santangeli P, Khanji MY, et al. (September 2020). "Recognizing COVID-19-related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management". Heart Rhythm. 17 (9): 1463–1471. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.05.001. PMC 7199677. PMID 32387246.

- ^ Basu-Ray I, Almaddah N, Adeboye A, Soos MP (2021). Cardiac Manifestations Of Coronavirus (COVID-19). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32310612. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Li X, Wang Y, Agostinis P, Rabson A, Melino G, Carafoli E, et al. (July 2020). "Is hydroxychloroquine beneficial for COVID-19 patients?". Cell Death & Disease. 11 (7): 512. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2721-8. PMC 7341710. PMID 32641681.

- ^ Zou F, Qian Z, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Bai J (September 2020). "Cardiac Injury and COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". CJC Open. 2 (5): 386–394. doi:10.1016/j.cjco.2020.06.010. PMC 7308771. PMID 32838255.

- ^ a b c Rathore SS, Rojas GA, Sondhi M, Pothuru S, Pydi R, Kancherla N, et al. (November 2021). "Myocarditis associated with Covid-19 disease: A systematic review of published case reports and case series". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 75 (11): e14470. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14470. PMID 34235815. S2CID 235768792.

- ^ Tavazzi G, Pellegrini C, Maurelli M, Belliato M, Sciutti F, Bottazzi A, et al. (May 2020). "Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock". European Journal of Heart Failure. 22 (5): 911–915. doi:10.1002/ejhf.1828. PMC 7262276. PMID 32275347.

- ^ Kesici S, Aykan HH, Orhan D, Bayrakci B (August 2020). "Fulminant COVID-19-related myocarditis in an infant". European Heart Journal. 41 (31): 3021. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa515. PMC 7314020. PMID 32531024.

- ^ Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Jiang C, Liu PP, Poutanen SM, Penninger JM, et al. (July 2009). "SARS-coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 39 (7): 618–625. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02153.x. PMC 7163766. PMID 19453650.

- ^ Nicin L, Abplanalp WT, Mellentin H, Kattih B, Tombor L, John D, et al. (May 2020). "Cell type-specific expression of the putative SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in human hearts". European Heart Journal. 41 (19): 1804–1806. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa311. PMC 7184464. PMID 32293672.

- ^ Payus AO, Liew Sat Lin C, Mohd Noh M, Jeffree MS, Ali RA (August 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 infection of the nervous system: A review of the literature on neurological involvement in novel coronavirus disease-(COVID-19)". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 20 (3): 283–292. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2020.4860. PMC 7416180. PMID 32530389.

- ^ a b Rabaan AA, Smajlović S, Tombuloglu H, Ćordić S, Hajdarević A, Kudić N, et al. (6 January 2023). "SARS-CoV-2 infection and multi-organ system damage: A review". Biomolecules and Biomedicine. 23 (1): 37–52. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2022.7762. ISSN 2831-090X. PMC 9901898. PMID 36124445.

- ^ Even Mild Cases Can Cause "COVID-19 Fog", Columbia University Irving Medical Center, 21 September 2020

- ^ Belluck P (11 October 2020), "How Brain Fog Plagues Covid-19 Survivors", The New York Times

- ^ Carod-Artal FJ (May 2020). "Neurological complications of coronavirus and COVID-19". Revista de Neurología. 70 (9): 311–322. doi:10.33588/rn.7009.2020179. PMID 32329044. S2CID 226200547.

- ^ Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, Ruiz L, Invernizzi P, Cuzzoni MG, et al. (June 2020). "Guillain-Barré Syndrome Associated with SARS-CoV-2". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (26): 2574–2576. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2009191. PMC 7182017. PMID 32302082.

- ^ a b c d e f g Agyeman AA, Chin KL, Landersdorfer CB, Liew D, Ofori-Asenso R (August 2020). "Smell and Taste Dysfunction in Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 95 (8): 1621–1631. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.030. PMC 7275152. PMID 32753137.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Marshall M (January 2021). "COVID's toll on smell and taste: what scientists do and don't know". Nature. 589 (7842): 342–343. Bibcode:2021Natur.589..342M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00055-6. PMID 33452511.

- ^ Gary JB, Gallagher L, Joseph PV, Reed D, Gudis DA, Overdevest JB (January 2023). "Qualitative Olfactory Dysfunction and COVID-19: An Evidence-Based Review with Recommendations for the Clinician". American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy. 37 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1177/19458924221120117. PMC 9379596. PMID 35957578.

- ^ Zhang R, Sun C, Chen X, Han Y, Zang W, Jiang C, et al. (April 2022). "COVID-19-Related Brain Injury: The Potential Role of Ferroptosis". Journal of Inflammation Research. 15: 2181–2198. doi:10.2147/JIR.S353467. PMC 8994634. PMID 35411172.

- ^ a b Marshall M (September 2020). "How COVID-19 can damage the brain". Nature. 585 (7825): 342–343. Bibcode:2020Natur.585..342M. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02599-5. PMID 32934351. S2CID 221746946.

- ^ Covid linked to 33-fold increase in risk of potentially fatal blood clot Archived 7 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian

- ^ Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ (December 2020). Solomon CG (ed.). "Severe Covid-19". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (25): 2451–2460. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2009575. PMID 32412710. S2CID 218649520.

- ^ "COVID rash: How the virus attacks the skin". www.colcorona.net. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ Massey PR, Jones KM (October 2020). "Going viral: A brief history of Chilblain-like skin lesions ("COVID toes") amidst the COVID-19 pandemic". Seminars in Oncology. 47 (5): 330–334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2020.05.012. PMC 7245293. PMID 32736881.

- ^ Jabalameli N, Rajabi F, Firooz A, Rezaei N (May 2022). "The Overlap between Genetic Susceptibility to COVID-19 and Skin Diseases". Immunological Investigations. 51 (4): 1087–1094. doi:10.1080/08820139.2021.1876086. PMID 33494631. S2CID 231711934.

- ^ Xu L, Liu J, Lu M, Yang D, Zheng X (May 2020). "Liver injury during highly pathogenic human coronavirus infections". Liver International. 40 (5): 998–1004. doi:10.1111/liv.14435. PMC 7228361. PMID 32170806.

- ^ Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB (May 2020). "Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review". JAMA. 323 (18): 1824–1836. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6019. PMID 32282022.

- ^ a b Mouffak S, Shubbar Q, Saleh E, El-Awady R (November 2021). "Recent advances in management of COVID-19: A review". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 143: 112107. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112107. PMC 8390390. PMID 34488083.

- ^ Plaçais L, Richier Q, Noël N, Lacombe K, Mariette X, Hermine O (February 2022). "Immune interventions in COVID-19: a matter of time?". Mucosal Immunology. 15 (2): 198–210. doi:10.1038/s41385-021-00464-w. PMC 8552618. PMID 34711920.

- ^ "Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents temporally related to COVID-19". World Health Organization (WHO). 15 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ HAN Archive – 00432 (Report). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 15 May 2020. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. (February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". Lancet. 395 (10223). Elsevier: 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- ^ a b Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ (March 2023). "Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 21 (3): 133–146. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2. PMC 9839201. PMID 36639608.

- ^ Castanares-Zapatero D, Chalon P, Kohn L, Dauvrin M, Detollenaere J, Maertens de Noordhout C, et al. (December 2022). "Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review". Annals of Medicine. 54 (1): 1473–1487. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2076901. PMC 9132392. PMID 35594336.

- ^ a b Torres-Castro R, Vasconcello-Castillo L, Alsina-Restoy X, Solis-Navarro L, Burgos F, Puppo H, et al. (November 2020). "Respiratory function in patients post-infection by COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Pulmonology. 27 (4). Elsevier BV: 328–337. doi:10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.10.013. PMC 7687368. PMID 33262076. S2CID 227162748.

- ^ Shaw B, Daskareh M, Gholamrezanezhad A (January 2021). "The lingering manifestations of COVID-19 during and after convalescence: update on long-term pulmonary consequences of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)". La Radiologia Medica. 126 (1): 40–46. doi:10.1007/s11547-020-01295-8. PMC 7529085. PMID 33006087.

- ^ Zhao YM, Shang YM, Song WB, Li QQ, Xie H, Xu QF, et al. (August 2020). "Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery". eClinicalMedicine. 25: 100463. doi:10.1016/j.ijtb.2020.11.003. PMC 7654356. PMID 32838236.

- ^ "COVID-19 Lung Damage". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ Taquet M, Sillett R, Zhu L, Mendel J, Camplisson I, Dercon Q, et al. (August 2022). "Neurological and psychiatric risk trajectories after SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies including 1 284 437 patients". The Lancet Psychiatry. 9 (10): 815–827. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00260-7. ISSN 2215-0366. PMC 9385200. PMID 35987197. S2CID 251626731.

- ^ a b c Graham EL, Clark JR, Orban ZS, Lim PH, Szymanski AL, Taylor C, et al. (May 2021). "Persistent neurologic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in non-hospitalized Covid-19 "long haulers"". Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 8 (5): 1073–1085. doi:10.1002/acn3.51350. PMC 8108421. PMID 33755344.

- ^ Landi F, Gremese E, Bernabei R, Fantoni M, Gasbarrini A, Settanni CR, et al. (Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group) (August 2020). "Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach". Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 32 (8): 1613–1620. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x. PMC 7287410. PMID 32529595.

- ^ Scordo KA, Richmond MM, Munro N (June 2021). "Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: Theoretical Basis, Identification, and Management". AACN Advanced Critical Care. 32 (2): 188–194. doi:10.4037/aacnacc2021492. PMID 33942071. S2CID 233722062.

- ^ García-Sánchez C, Calabria M, Grunden N, Pons C, Arroyo JA, Gómez-Anson B, et al. (March 2022). "Neuropsychological deficits in patients with cognitive complaints after COVID-19". Brain and Behavior. 12 (3): e2508. doi:10.1002/brb3.2508. PMC 8933779. PMID 35137561.