Sylhet Division

Sylhet Division

সিলেট বিভাগ ꠍꠤꠟꠐ ꠛꠤꠜꠣꠉ Śilhôṭ-Jalalabad | |

|---|---|

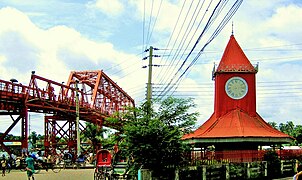

Clockwise from the top: Jaflong, Shahid Siraj Lake, Shah Jalal Dargah, Keane Bridge & Ali Amjad's Clock, Jaintia Princess Irāvati's Inn, and Ratargul Swamp Forest | |

| Nickname: | |

| Coordinates: 24°30′N 91°40′E / 24.500°N 91.667°E | |

| Country | |

| Established | 1995 |

| Capital and largest city | Sylhet |

| Government | |

| • Divisional Commissioner | Abu Ahmed Siddique[2] |

| • Parliamentary constituency | Jatiya Sangsad (19 seats) |

| Area | |

| 12,298.4 km2 (4,748.4 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 334.67 m (1,098 ft) |

| Population | |

| 11,034,952 (Enumerated) | |

| • Urban | 2,065,498 |

| • Rural | 8,968,558 |

| • Metro | 532,748 |

| • Adjusted Population[4] | 11,415,113 |

| Demonym | Sylheti |

| Demographics | |

| • Literacy rate | 71.92% |

| Languages | |

| • Official language | Bengali[5] |

| • Regional language | Sylheti[6][7] |

| • Minority Languages | |

| Time zone | UTC+6 (BST) |

| ISO 3166 code | BD-G |

| HDI (2019) | 0.631[14] medium |

| Notable sport teams | |

| Website | sylhetdiv |

Sylhet Division (Bengali: সিলেট বিভাগ; Sylheti: ꠍꠤꠟꠐ ꠛꠤꠜꠣꠉ)[15][16][17][18] is the northeastern division of Bangladesh. It is bordered by the Indian states of Meghalaya, Assam and Tripura to the north, east and south respectively, and by the divisions of Chittagong to the southwest and Dhaka and Mymensingh to the west.

Prior to the Partition in 1947, it included Karimganj subdivision (presently in Barak Valley, Assam, India). However, Karimganj (including the thanas of Badarpur, Patharkandi and Ratabari) was inexplicably severed from Sylhet by the Radcliffe Boundary Commission. According to Niharranjan Ray, it was partly due to a plea from a delegation led by Abdul Matlib Mazumdar.[19]

Etymology

[edit]

The Sylhet Division is named after its headquarters, the city of Sylhet. Sylhet is the anglicisation of শিলহট (Śilhôṭ), one of the archaic native names for the city.[citation needed] The local name is generally thought to be directly derived from শ্রীহট্ট (Śrīhaṭṭa), the Sanskrit name of the city.[20] The city of Śrīhaṭṭa takes its name from Śrīhaṭṭanātha, the tutelary deity of the Nātha dynasty who promoted the early settlement of Nāthas in the Surma and Barak valleys between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, founding the Śrīhaṭṭa janapada and establishing Śrīhaṭṭanātha idols across the region.[21] The later Hindu rajas of Sylhet, such as Gour Govinda, continued to pay tribute to the deity as Hāṭkeśvara or Haṭṭanātha as evident from the Devipurana and copper-plate inscriptions.[22]

History

[edit]

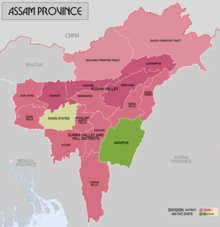

In 1874, the current Sylhet Division, which included Karimganj District, was entirely known as the 'Sylhet district'. On 16 February 1874, Sylhet was separated from mainland Bengal to be made a part of the non-regulation Chief Commissioner's Province of Assam (Northeast Frontier Province) in order to facilitate Assam's commercial development.[23][24] The people of Sylhet submitted a memorandum to the Viceroy protesting the inclusion in Assam.[25] The protests subsided when the Viceroy, Lord Northbrook, visited Sylhet to reassure the people that education and justice would be administered from Bengal,[26] and when the people in Sylhet saw the opportunity of employment in tea estates in Assam and a market for their produce.[27] In 1905, Sylhet district rejoined Bengal as a part of the new Surma Valley Division of Eastern Bengal and Assam. In 1912, the then Sylhet district was once again moved to the newly created Assam Province alongside the other districts of the Surma Valley Division.

Historically, the entire Sylhet region was a single district within the Surma Valley and Hill Districts Division as part of the Assam Province. In 1947, a referendum was held in the Sylhet district, the people of the whole district voting in favour of succession to Pakistan. However, the district's Karimganj subdivision was given to India by Cyril Radcliffe, after apparently being pleaded by a delegation led by Abdul Matlib Mazumdar. The four other subdivisions (North Sylhet, South Sylhet, Habiganj and Sunamganj) joined the Dominion of Pakistan; subsequently forming East Bengal's 'Sylhet district' in the Chittagong division.

Following the Independence of Bangladesh in 1971, Sylhet became part of the newly formed country. In 1984, the four subdivisions of Sylhet district were upgraded to districts as part of H M Ershad's decentralisation programme. The four districts remained in the Chittagong Division until 1995 when they formed the new Sylhet Division.

The Sylhet Division has a "friendship link" with the city of St Albans, in the United Kingdom. The link was established in 1988 when the St Albans District Council supported a housing project in Sylhet as part of the International Year of Shelter for the Homeless. Sylhet was chosen because it is the area of origin for the largest ethnic minority group in St Albans.[28] Sylhet also has many "friendship links" with other cities in the United Kingdom, as the majority of the half-million British Bangladeshis have origins in Sylhet. This includes places such as Rochdale, Oldham, London, and many more places.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

The area around Sylhet is a traditional tea growing area. The Surma Valley is covered with terraces of tea gardens and tropical forests. Srimangal is known as the tea capital of Bangladesh; for miles around, tea gardens are visible on the hill slopes.

The area has over 150 tea gardens, including three of the largest tea plantations in the world, both in terms of area and production. Nearly 300,000 workers, of which more than 75% are women, are employed on the tea estates. Employers prefer to engage women for plucking tea leaves since they do a better job than, but are paid less than, men. A recent drought has killed nearly a tenth of the tea shrubs.

The plantations, or gardens, were mostly developed during the British Raj. The plantations were started by the British, and the managers still live in the white timber houses built during the Raj. The bungalows stand on huge lawns. The service and the lifestyle of managers are still unchanged.

Numerous projects and businesses in the city and in large towns have been funded by Sylhetis living and working abroad. As of 1986, an estimated 95 percent of ethnic British Bangladeshis originated from or had ancestors from the Sylhet region.[29] The Bangladesh government has set up a special Export Processing Zone (EPZ) in Sylhet, in order to attract foreign investors, mainly from the UK.

Sylhet has also benefited from tourism. There are many natural landmarks people tend to visit, such as the Keane Bridge, Ali Amjad's Clock, Lalakhal, Jaflong, Madhabkunda waterfall, Ratargul Swamp Forest, Hakaluki Haor, Lawachara National Park, Tanguar Haor and Bichnakandi.[30] Sylhet is also considered to be the spiritual capital of Bangladesh, due to the resting place of Shah Jalal, a Sufi saint who spread Islam in Bangladesh, along with hundreds of his disciples. The Sylhet Shahi Eidgah is a famous place where Eid prayers take place and it is one of the largest Eidgahs in Bangladesh, built by Farhad Khan during the reign of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. There are a number of hotels and resorts, particularly in Sreemangal Upazila and Bahubal Upazila.

Governance

[edit]

In 1995, Sylhet split from the Chittagong Division and was declared the 6th division of the country. The Sylhet Division is overseen by the Divisional Commissioner, the current Divisional Commissioner is Md. Mashiur Rahman. The Sylhet Division is divided into four districts (Habiganj, Moulvibazar, Sunamganj and Sylhet) and further divided into 35 upazilas (sub-districts). These upazilas are further divided into 323 union parishads. Each union is roughly divided into 9 wards before going to village-level. There are roughly 10,185 villages in the Division. The Division hosts 19 Municipal corporations known as pourashavas, and one city corporation in Sylhet city. It also has 19 Parliamentary constituencies. The headquarters of the Sylhet Division is the city of Sylhet in Sylhet Sadar Upazila, Sylhet District. Pre-partition Sylhet's Karimganj has been governed by India since 1947.

| Name | Capital | Area (km2)[31] | Population 1991 Census |

Population 2001 Census |

Population 2011 Census |

Population

2022 Census |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habiganj District | Habiganj | 2,536.58 | 1,526,609 | 1,757,665 | 2,089,001 | 2,358,747 |

| Moulvibazar District | Moulvibazar | 2,601.84 | 1,376,566 | 1,612,374 | 1,919,062 | 2,123,349 |

| Sunamganj District | Sunamganj | 3,669.58 | 1,708,563 | 2,013,738 | 2,467,968 | 2,695,294 |

| Sylhet District | Sylhet | 3,490.40 | 2,153,301 | 2,555,566 | 3,434,188 | 3,856,974 |

| Total District | 4 | 12,298.4 | 6,765,039 | 7,939,343 | 9,910,219 | 11,034,364 |

| District | Upazila | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habiganj District | |||||||

| Moulvibazar District | |||||||

| Sunamganj District | |||||||

| Sylhet District | |||||||

Geography

[edit]

Geographically the region is surrounded by hillocks (known as tillas) from all three sides except its western plain boundary with the rest of Bengal. In the south of the region (Habiganj, Moulvibazar), eight hill ranges enter the plains of Sylhet running uniformly from the west to the east. They are: Raghunandan, Dinarpur-Shatgaon, Balishira, Bhanugach-Rajkandi, Hararganj-Singla, Patharia, Pratapgarh-Duhalia and Sorrispur-Siddheswar hill ranges. At the centre of the region is also an isolated range known as the Ita Hills.[32]

The region is considered one of the most picturesque and archaeologically rich regions in South Asia. It is home to three national parks; the Lawachara National Park, Khadim Nagar National Park and Satchari National Park, as well as numerous smaller parks and forests such as the Ratargul Swamp Forest, Rema-Kalenga Wildlife Sanctuary. Its burgeoning economy has contributed to the regional attractions of landscapes filled with fragrant orange and pineapple gardens as well as tea plantations. The region has a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am) bordering on a humid subtropical climate (Cwa) at higher elevations. The rainy season from April to October is hot and humid with very heavy showers and thunderstorms almost every day, whilst the short dry season from November to February is very warm and fairly clear. Nearly 80% of the annual average rainfall of 4,200 millimetres (170 in) occurs between May and September.[33]

The physiography of the division consists mainly of hill soils, encompassing a few large depressions known locally as "beels" which can be mainly classified as oxbow lakes, caused by tectonic subsidence primarily during the earthquake of 1762.[32]

Geologically, the division is complex having diverse sacrificial geomorphology; high topography of Plio-Miocene age such as the Khasi and Jaintia Hills and small hillocks along the border. At the centre there is a vast low laying flood plain of recent origin with saucer shaped depressions, locally called haors. There are many haors in the region and the largest ones include Hakaluki, Kawadighi, Tanguar and Hail. Available limestone deposits in different parts of the region suggest that the whole area was under the ocean in the Oligo-Miocene. In the last 150 years, three major earthquakes hit the city, at a magnitude of at least 7.5 on the Richter Scale, the last one took place in 1918, although many people are unaware that Sylhet lies on an earthquake prone zone.[34]

Flora and fauna

[edit]The region is home to the Asian elephant and the One-horned rhinoceros, mostly towards the south. Tigers and leopards were once found throughout the region. Other notable fauna include the Sambar deer, Indian hog deer, Sylhet hara and Sylhet roofed turtle.[35]

The Asian elephant were once found in small numbers in places such as Chapghat, Bhanugach, Chamtolla, Mahram and the Raghunandan hills. More abundantly they are found near streams in Singla and Langai.[32]

Culture

[edit]Language

[edit]

The official language of Sylhet is Bengali, which is used in education and all government affairs in the division. Sylheti is the most widely spoken in the division. At one point, the Sylheti Nagri script was notably popular in its use to write Islamic puthis. The Adivasis and tea labourers brought over during the British colonial rule also have their own native languages such as Khasi, Kuki, Laiunghtor, Meitei, Bishnupriya Manipuri, Hajong, Garo, Odia, Kurmi creole, Hindi, Bhumij and Tripuri.[36]

Architecture

[edit]The intense building of mosques which took place during the Sultanate era indicates the rapidity with which the locals converted to Islam. Today, mosques are present in every Muslim-inhabited village. Bengali mosques are normally covered with several small domes and curved brick roofs decorated with terracotta. Ponds are often located beside a mosque.[37]

Faujdar Farhad Khan built Sylhet Shahi Eidgah in the 1660s under the reign of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. It stands as the largest eidgah of the region.[38]

In 1872, Nawab Moulvi Ali Ahmed Khan of Prithimpassa constructed Ali Amjad's Clock, named after his son, in Sylhet City.[39][40][41] In 1936, a bridge was constructed across the Surma River known as the Keane Bridge. These two historic landmarks are known as the gateway to Sylhet city.

Assam-type architecture developed in Sylhet region under Assam Province during the late modern period.

- Architecture of Sylhet

-

Sylhet Shahi Eidgah entrance

-

Modern architecture in Sylhet

Sports and games

[edit]

Cricket is the most popular sport in Sylhet. Regional cricket teams include Sylhet Thunder, East Zone and the Sylhet Division cricket team. Football is also a common sport and the multi-use Saifur Rahman Stadium are known to host football matches. Beanibazar SC has played in the Bangladesh League. The home stadium of the football club, Sheikh Russel KC, is in Sylhet District Stadium. Board and home games such as Dosh Fochish and its modern counterpart Ludo, as well as Carrom Board, Sur-Fulish, Khanamasi and Chess, are very popular in the region. Nowka Bais is a common traditional rowing competition during the monsoon season when rivers are filled up, and much of the land is under water. Fighting sports include Kabaddi, Latim and Lathi khela.

Demography

[edit]

The division's population is over 12 million and Bengalis make up a large majority of the region's population. The tribal and Adivasi population tend to live in secluded rural areas of the region primarily near the hills and tea gardens. They are made up of several ethnic groups such as the Bishnupriya Manipuris, Khasi, Lalengs, Tripuris, Meiteis, Garos, and Kukis. In the nineteenth century, the British brought over indigenous peoples from other parts of British India to work as tea garden labourers such as the Kurmis, Musahars, Bauris, Beens, Bonaz, Sabar and Bhumij amongst others.[42]

Religion

[edit]Islam is the largest religion in the whole region practised by the Bengali Muslims. Sunni Islam is the largest denomination with majority following the Hanafi school of law although some also follow the Shafi'i and Hanbali madhhabs.[43] There are significant numbers of people who follow Sufi ideals similar to the Barelvis, the most influential is the teachings of Abdul Latif Chowdhury Fultali of Zakiganj – a descendant of one of the disciples of Shah Jalal.[44] The revivalist Deobandi movement is also popular in the region with Jamia Tawakkulia Renga being a notable centre and many are part of the Tablighi Jamaat. Haji Shariatullah's Faraizi movement was very popular during the British period and Wahhabism is adopted by some upper-class families.[45] The Ahmadiyya community is mostly concentrated in Selbaras, which was the ancestral home of Ahmad Toufiq Choudhury, the leader of Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at Bangladesh.[46][47]

There is a very small minority of Shia Muslims who gather every year during Ashura for the Mourning of Muharram processions. Places of procession include the Prithimpasha Nawab Bari in Kulaura, home to a royal Shia family, as well as Rajtila.

Hinduism is the second largest religion practised by the Bengali Hindus as well as majority of the Bishnupriya Manipuri, Beens, Bhumij, Bonaz, Sabar, Musahar, Kurmi, Lalengs, Bauris and Tripuri population. Sylhet has the largest concentration of Hindus in Eastern Bengal and is a part of the Shakta pitha.

Other minority religions include Christianity (including the Roman Catholic Diocese of Sylhet and Sylhet Presbyterian Synod), Ka Niam Khasi, Sanamahism, Songsarek as well as animism. In the early 20th century, there were over a hundred Marwaris from Rajasthan that were living in Sylhet, mostly as merchants and followed Jainism.[35]: 90

There was a presence of Sikhism in Sylhet after Guru Nanak's visit in 1508 to spread the religion. Kahn Singh Nabha has stated that in memory of Nanak's visit, Gurdwara Sahib Sylhet was established.[citation needed] This Gurdwara was visited twice by Tegh Bahadur and many hukamnamas were issued to this temple by Guru Gobind Singh. In 1897, the gurdwara fell down after the earthquake.

In popular culture

[edit]- In season 4, episode 6, of Call the Midwife, the midwives tend to a woman from the Sylhet Division.[48]

See also

[edit]- Divisions of Bangladesh

- Folk deities of Sylhet

- List of people from Sylhet

- Sylhet roofed turtle

- Sylhet Hara

References

[edit]- ^ https://metrosylhet.judiciary.gov.bd/en/menu/page/history-of-district-judiciary

- ^ "List of Divisional Commissioners". Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Kala Pahar (The Highest peak of Greater Sylhet and Northern Bangladesh)". Wikiloc | Trails of the World. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f National Report (PDF). Population and Housing Census 2022. Vol. 1. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. November 2023. p. 386. ISBN 978-9844752016.

- ^ "The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh". Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Sylheti". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ চৌধুরী, ফারজানা (18 June 2021). "যুক্তরাষ্ট্রে আঞ্চলিক ভাষার স্বীকৃতি পেল 'সিলেটি' ভাষা" (in Bengali). Prothom Alo. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "বিলুপ্তির পথে হাজং ভাষাবৈচিত্র্য". Janakantha. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

দেশের উত্তর-পূর্বাঞ্চলের নেত্রকোনা, ময়মনসিংহ, শেরপুর, সুনামগঞ্জ ও সিলেটের আংশিক এলাকার ১০৮টি গ্রামে হাজং সম্প্রদায়ের বসবাস।

- ^ Mintu Deshwara, Pinaki Roy (21 February 2021). "The last of the Kharia speakers". Retrieved 2 January 2024.

After our death, nobody will speak this language [Kharia]. I tried to teach the language to the younger people but they do not show interest and laugh at me when I speak in Kharia.

- ^ নিজস্ব প্রতিবেদক (11 February 2023). "খাসি ভাষা ধরে রাখার চেষ্টায় বিদ্যালয় চালু". Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ নিজস্ব প্রতিবেদক (11 December 2023). "বিপন্ন 'কুরুখ' ভাষা রক্ষায় নতুন উদ্যোগ". Prothom Alo. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Jengcham, Subhas (2012). "Bonaz". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ "Bangladesh". Ethnologue. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Mowbray, Harris (24 June 2021). "Propose to include Sylheti Nagri numerals in the UCS" (PDF).

- ^ Omniglot (16 March 2023). "Sylheti at a glance".

- ^ Simard, Candide (2007). "Introducing the Sylheti language and its people".

- ^ Camden, SOAS (11 December 2021). "Sylheti Project is SOAS Camden".

- ^ Ray, Niharranjan (1 January 1980). Bangalir itihas (in Bengali). Paschimbanga Samiti. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Monsur Musa (1999). "History of the Study of the Dialect of Sylhet: Some Problems". In Sharif Uddin Ahmed (ed.). Sylhet: History and Heritage. Bangladesh Itihas Samiti. p. 588. ISBN 978-984-31-0478-6.

- ^ Chowdhury, Mujibur Rahman (31 July 2019). "গৌড়-বঙ্গে মুসলিম বিজয় এবং সুফি-সাধকদের কথা" [Muslim conquest in Gauḍa-Vaṅga and discussion about Sufi ascetics]. Sylheter Dak (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Choudhury, Achyut Charan (2000) [1916]. "উত্তর শ্রীহট্টের নামতত্ত্ব". Srihatter Itibritta: Uttorangsho (in Bengali). Kolkata: Kotha. p. 21. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Tanweer Fazal (2013). Minority Nationalisms in South Asia. Routledge. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-317-96647-0.

- ^ Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 261. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785. S2CID 145546471.

To make [the Province] financially viable, and to accede to demands from professional groups, [the colonial administration] decided in September 1874 to annex the Bengali-speaking and populous district of Sylhet.

- ^ Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 261. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785. S2CID 145546471.

A memorandum of protest against the transfer of Sylhet was submitted to the viceroy on 10 August 1874 by leaders of both the Hindu and Muslim communities.

- ^ Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 262. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785. S2CID 145546471.

It was also decided that education and justice would be administered from Calcutta University and the Calcutta High Court respectively.

- ^ Hossain, Ashfaque (2013). "The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (1): 262. doi:10.1017/S0026749X1200056X. JSTOR 23359785. S2CID 145546471.

They could also see that the benefits conferred by the tea industry on the province would also prove profitable for them. For example, those who were literate were able to obtain numerous clerical and medical appointments in tea estates, and the demand for rice to feed the tea labourers noticeably augmented its price in Sylhet and Assam enabling the Zaminders (mostly Hindu) to dispose of their produce at a better price than would have been possible had they been obliged to export it to Bengal.

- ^ Sylhet, Bangladesh Archived 19 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine.St.Albans District Council.

- ^ Gardner, Katy (July 1992). "International migration and the rural context in Sylhet". New Community. 18 (4): 579–590. doi:10.1080/1369183X.1992.9976331.

- ^ "Best Things to Do in Sylhet Division of Bangladesh". Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Sajahan Miah (2012). "Sylhet Division". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ a b c E M Lewis (1868). "Sylhet District". Principal Heads of the History and Statistics of the Dacca Division. Calcutta: Calcutta Central Press Company. pp. 281–326.

- ^ Monthly Averages for Sylhet, BGD Archived 1 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine MSN Weather. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ Siddiquee, Iqbal (10 February 2006). "Sylhet growing as a modern urban centre". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ a b B C Allen (1905). Assam District Gazetteers. Vol. 2. Calcutta: Government of Assam.

- ^ Jengcham, Subhash. "Mushahar". Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Oleg Grabar (1989). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Brill Archive. pp. 58–72. ISBN 978-90-04-09050-7. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Ali Ahmad. "Vide". Journal of Assam Research Society. VIH: 26.

- ^ Kadir Jibon, Abdul (11 September 2018). "Ali Amjad's Tower Clock". Daily Sun. Dhaka. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ Alam, Mahabub (20 July 2016). এখনও সময় জানায় আমজাদের সেই ঘড়ি [Ali Amjad's clock still telling the time!]. Banglanews24.com (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Chowdhury, Aftab (5 October 2016). আলী আমজাদের ঘড়ি [The Clock of Ali Amjad]. Bangladesh Pratidin (in Bengali). Dhaka. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Jengcham, Subhash. "Bhumij". Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Islam in Bangladesh". OurBangla. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ Dr David Garbin (17 June 2005). "Bangladeshi Diaspora in the UK : Some observations on socio-culturaldynamics, religious trends and transnational politics" (PDF). University of Surrey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ Hunter, William Wilson (1875). "District of Sylhet: Administrative History". A Statistical Account of Assam. Vol. 2.

- ^ AK Rezaul Karim (15 October 2005). "Zikr-e-Khair". The Fortnightly Ahmadi (in Bengali). 68 (6/7). Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at, Bangladesh.

- ^ "Death Anniversary". The Daily Star. 10 August 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ "'Call The Midwife' Season 4 Premiere: Nurse Barbara Learns About Culture As Cynthia Returns in Sneak Peek [VIDEO]". ENSTARZ. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.