Sydney Harbour Bridge

Sydney Harbour Bridge | |

|---|---|

View from Port Jackson, October 2019 | |

| Coordinates | 33°51′08″S 151°12′38″E / 33.85222°S 151.21056°E |

| Carries | Bradfield Highway Cahill Expressway North Shore railway line footpath cycleway |

| Crosses | Port Jackson |

| Locale | Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Begins | Dawes Point |

| Ends | Milsons Point |

| Owner | Transport for NSW |

| Maintained by | Transport for NSW |

| Preceded by | Gladesville Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Through arch bridge |

| Trough construction | Steel |

| Pier construction | Granite-faced concrete |

| Total length | 1,149 m (3,770 ft) |

| Width | 48.8 m (160 ft) |

| Height | 134 m (440 ft) |

| Longest span | 503 m (1,650 ft) |

| No. of spans | 1 |

| Clearance below | 49 m (161 ft) at mid-span |

| No. of lanes | 8 |

| Rail characteristics | |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrified | 1500 V DC overhead |

| History | |

| Constructed by | Dorman Long |

| Construction start | 28 July 1923 |

| Construction end | 19 January 1932 |

| Opened | 19 March 1932 |

| Inaugurated | 19 March 1932 |

| Replaced by | Sydney Harbour Tunnel (concurrent use since 1992) |

| Statistics | |

| Toll | Time-of-day (southbound only) |

| Official name | Sydney Harbour Bridge, Bradfield Hwy, Dawes Point – Milsons Point, NSW, Australia |

| Type | National Heritage List |

| Designated | 19 March 2007 |

| Reference no. | 105888 |

| Class | Historic |

| Place File No. | 1/12/036/0065 |

| Official name | Sydney Harbour Bridge, approaches and viaducts (road and rail); Pylon Lookout; Milsons Point Railway Station; Bradfield Park; Bradfield Park North; Dawes Point Park; Bradfield Highway |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 25 June 1999 |

| Reference no. | 781 |

| Type | Road Bridge |

| Category | Transport – Land |

| Location | |

| |

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is a steel through arch bridge in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, spanning Sydney Harbour from the central business district (CBD) to the North Shore. The view of the bridge, the Harbour, and the nearby Sydney Opera House is widely regarded as an iconic image of Sydney, and of Australia itself. Nicknamed "The Coathanger" because of its arch-based design, the bridge carries rail, vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian traffic.[1][2]

Under the direction of John Bradfield of the New South Wales Department of Public Works, the bridge was designed and built by British firm Dorman Long of Middlesbrough, and opened in 1932.[3][4] The bridge's general design, which Bradfield tasked the NSW Department of Public Works with producing, was a rough copy of the Hell Gate Bridge in New York City. The design chosen from the tender responses was original work created by Dorman Long, who leveraged some of the design from its own Tyne Bridge.[5]

It is the tenth-longest spanning-arch bridge in the world and the tallest steel arch bridge, measuring 134 m (440 ft) from top to water level.[6] It was also the world's widest long-span bridge, at 48.8 m (160 ft) wide, until construction of the new Port Mann Bridge in Vancouver was completed in 2012.[7][8]

Structure

[edit]

The southern end of the bridge is located at Dawes Point in The Rocks area, and the northern end at Milsons Point on the lower North Shore. There are six original lanes of road traffic through the main roadway, plus an additional two lanes of road traffic on its eastern side, using lanes that were formerly tram tracks. Adjacent to the road traffic, a path for pedestrian use runs along the eastern side of the bridge, whilst a dedicated path for bicycle use runs along the western side. Between the main roadway and the western bicycle path lies the North Shore railway line.

The main roadway across the bridge is known as the Bradfield Highway and is about 2.4 km (1.5 mi) long, making it one of the shortest highways in Australia.[9]

Arch

[edit]

The arch is composed of two 28-panel arch trusses; their heights vary from 18 m (59 ft) at the centre of the arch, to 57 m (187 ft) at the ends next to the pylons.[10]

The arch has a span of 504 m (1,654 ft), and its summit is 134 m (440 ft) above mean sea level; expansion of the steel structure on hot days can increase the height of the arch by 18 cm (7.1 in).[11]

The total weight of the steelwork of the bridge, including the arch and approach spans, is 52,800 tonnes (52,000 long tons; 58,200 short tons), with the arch itself weighing 39,000 tonnes (38,000 long tons; 43,000 short tons).[12] About 79% of the steel, specifically those technical sections constituting the curve of the arch, was imported pre-formed from England, with the rest being sourced from the Newcastle Steelworks.[13] On site, Dorman Long & Co set up two workshops at Milsons Point, at the site of the present day Luna Park, and fabricated the steel into the girders and other required parts.[13]

The bridge is held together by six million Australian-made hand-driven rivets supplied by the McPherson company of Melbourne,[14][15] the last being driven through the deck on 21 January 1932.[13][16] The rivets were heated red-hot and inserted into the plates; the headless end was immediately rounded over with a large pneumatic rivet gun.[17] The largest of the rivets used weighed 3.5 kg (8 lb) and was 39.5 cm (15.6 in) long.[12][18] The practice of riveting large steel structures, rather than welding, was, at the time, a proven and understood construction technique, whilst structural welding had not at that stage been adequately developed for use on the bridge.[17]

Pylons

[edit]

At each end of the arch stands a pair of 89-metre-high (292 ft) concrete pylons, faced with granite.[19] The pylons were designed by the Scottish architect Thomas S. Tait,[20] a partner in the architectural firm John Burnet & Partners.[21]

Some 250 Australian, Scottish, and Italian stonemasons and their families relocated to a temporary settlement at Moruya, 300 km (186 mi) south of Sydney, where they quarried around 18,000 m3 (635,664 cu ft) of granite for the bridge pylons.[13] The stonemasons cut, dressed, and numbered the blocks, which were then transported to Sydney on three ships built specifically for this purpose. The Moruya quarry was managed by John Gilmore, a Scottish stonemason who emigrated with his young family to Australia in 1924, at the request of the project managers.[13][22][23] The concrete used was also Australian-made and supplied from Kandos.[24][25][26][27]

Abutments at the base of the pylons are essential to support the loads from the arch and hold its span firmly in place, but the pylons themselves have no structural purpose. They were included to provide a frame for the arch panels and to give better visual balance to the bridge. The pylons were not part of the original design, and were only added to allay public concern about the structural integrity of the bridge.[28]

Although originally added to the bridge solely for their aesthetic value, all four pylons have now been put to use. The south-eastern pylon contains a museum and tourist centre, with a 360° lookout at the top providing views across the Harbour and city. The south-western pylon is used by Transport for NSW to support its CCTV cameras overlooking the bridge and the roads around that area. The two pylons on the north shore include venting chimneys for fumes from the Sydney Harbour Tunnel, with the base of the southern pylon containing the Transport for NSW maintenance shed for the bridge, and the base of the northern pylon containing the traffic management shed for tow trucks and safety vehicles used on the bridge.

In 1942, the pylons were modified to include parapets and anti-aircraft guns designed to assist in both Australia's defence and general war effort.[29]

History

[edit]Early proposals

[edit]

There had been plans to build a bridge as early as 1814, when convict and noted architect Francis Greenway reputedly proposed to Governor Lachlan Macquarie that a bridge be built from the northern to the southern shore of the harbour.[6][30] In 1825, Greenway wrote a letter to the then "The Australian" newspaper stating that such a bridge would "give an idea of strength and magnificence that would reflect credit and glory on the colony and the Mother Country".[30]

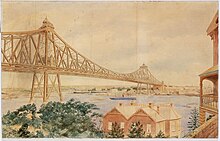

Nothing came of Greenway's suggestions, but the idea remained alive, and many further suggestions were made during the nineteenth century. In 1840, naval architect Robert Brindley proposed that a floating bridge be built. Engineer Peter Henderson produced one of the earliest known drawings of a bridge across the harbour around 1857. A suggestion for a truss bridge was made in 1879, and in 1880 a high-level bridge estimated at £850,000 was proposed.[30]

In 1900, the Lyne government committed to building a new Central railway station and organised a worldwide competition for the design and construction of a harbour bridge, overseen by Minister for Public Works Edward William O'Sullivan.[31] G.E.W. Cruttwell, a London based engineer, was awarded the first prize of £1,000. Local engineer Norman Selfe submitted a design for a suspension bridge and won the second prize of £500. In 1902, when the outcome of the first competition became mired in controversy, Selfe won a second competition outright, with a design for a steel cantilever bridge. The selection board were unanimous, commenting that, "The structural lines are correct and in true proportion, and... the outline is graceful".[32] However due to an economic downturn and a change of government at the 1904 NSW State election construction never began.[33]

A unique three-span bridge was proposed in 1922 by Ernest Stowe with connections at Balls Head, Millers Point, and Balmain with a memorial tower and hub on Goat Island.[34][35]

Planning

[edit]In 1914, John Bradfield was appointed Chief Engineer of Sydney Harbour Bridge and Metropolitan Railway Construction, and his work on the project over many years earned him the legacy as the father of the bridge.[3] Bradfield's preference at the time was for a cantilever bridge without piers, and in 1916 the NSW Legislative Assembly passed a bill for such a construction, however it did not proceed as the Legislative Council rejected the legislation on the basis that the money would be better spent on the war effort.[30]

Following World War I, plans to build the bridge again built momentum.[6] Bradfield persevered with the project, fleshing out the details of the specifications and financing for his cantilever bridge proposal, and in 1921 he travelled overseas to investigate tenders. His confidential secretary Kathleen M. Butler handled all the international correspondence during his absence, her title belying her role as project manager as well as a technical adviser.[36][37] On return from his travels Bradfield decided that an arch design would also be suitable[30] and he and officers of the NSW Department of Public Works prepared a general design[6] for a single-arch bridge based upon New York City's Hell Gate Bridge.[5][38] In 1922 the government of George Fuller passed the Sydney Harbour Act 1922, specifying the construction of a high-level cantilever or arch bridge across the Harbour between Dawes Point and Milsons Point, along with construction of necessary approaches and electric railway lines,[30] and worldwide tenders were invited for the project.[3]

As a result of the tendering process, the government received twenty proposals from six companies; on 24 March 1924 the contract was awarded to Dorman Long & Co of Middlesbrough, England well known as the contractors who later built the similar Tyne Bridge in Newcastle Upon Tyne, for an arch bridge at a quoted price of AU£4,217,721 11s 10d.[3][30] The arch design was cheaper than alternative cantilever and suspension bridge proposals, and also provided greater rigidity making it better suited for the heavy loads expected.[30] In 1924, Kathleen Butler travelled to London to set up the project office within those of Dorman, Long & Co., "attending the most difficult and technical questions and technical questions in regard to the contract, and dealing with a mass of correspondence".[39]

Bradfield and his staff were ultimately to oversee the bridge design and building process as it was executed by Dorman Long and Co, whose Consulting Engineer, Sir Ralph Freeman of Sir Douglas Fox and Partners, and his associate Georges Imbault, carried out the detailed design and erection process of the bridge.[3] Architects for the contractors were from the British firm John Burnet & Partners of Glasgow, Scotland.[21] Lawrence Ennis, of Dorman Long, served as Director of Construction and primary onsite supervisor throughout the entire build, alongside Edward Judge, Dorman Long's Chief Technical Engineer, who functioned as Consulting and Designing Engineer.

The building of the bridge coincided with the construction of a system of underground railways beneath Sydney's CBD, known today as the City Circle, and the bridge was designed with this in mind. The bridge was designed to carry six lanes of road traffic, flanked on each side by two railway tracks and a footpath. Both sets of rail tracks were linked into the underground Wynyard railway station on the south (city) side of the bridge by symmetrical ramps and tunnels. The eastern-side railway tracks were intended for use by a planned rail link to the Northern Beaches;[40] in the interim they were used to carry trams from the North Shore into a terminal within Wynyard station, and when tram services were discontinued in 1958, they were converted into extra traffic lanes. The Bradfield Highway, which is the main roadway section of the bridge and its approaches, is named in honour of Bradfield's contribution to the bridge.

Construction

[edit]

Bradfield visited the site sporadically throughout the eight years it took Dorman Long to complete the bridge. Despite having originally championed a cantilever construction and the fact that his own arched general design was used in neither the tender process nor as input to the detailed design specification (and was anyway a rough copy of the Devil's Gate bridge produced by the NSW Works Department), Bradfield subsequently attempted to claim personal credit for Dorman Long's design. This led to a bitter argument, with Dorman Long maintaining that instructing other people to produce a copy of an existing design in a document not subsequently used to specify the final construction did not constitute personal design input on Bradfield's part. This friction ultimately led to a large contemporary brass plaque being bolted very tightly to the side of one of the granite columns of the bridge to makes things clear.[41]

The official ceremony to mark the turning of the first sod occurred on 28 July 1923, on the spot at Milsons Point where two workshops to assist in building the bridge were to be constructed.[42][43]

An estimated 469 buildings on the north shore, both private homes and commercial operations, were demolished to allow construction to proceed, with little or no compensation being paid. Work on the bridge itself commenced with the construction of approaches and approach spans, and by September 1926 concrete piers to support the approach spans were in place on each side of the harbour.[42]

As construction of the approaches took place, work was also started on preparing the foundations required to support the enormous weight of the arch and loadings. Concrete and granite faced abutment towers were constructed, with the angled foundations built into their sides.[42]

Once work had progressed sufficiently on the support structures, a giant creeper crane was erected on each side of the harbour.[44] These cranes were fitted with a cradle, and then used to hoist men and materials into position to allow for erection of the steelwork. To stabilise works while building the arches, tunnels were excavated on each shore with steel cables passed through them and then fixed to the upper sections of each half-arch to stop them collapsing as they extended outwards.[42]

Arch construction itself began on 26 October 1928. The southern end of the bridge was worked on ahead of the northern end, to detect any errors and to help with alignment. The cranes would "creep" along the arches as they were constructed, eventually meeting up in the middle. In less than two years, on 19 August 1930, the two halves of the arch touched for the first time. Workers riveted both top and bottom sections of the arch together, and the arch became self-supporting, allowing the support cables to be removed. On 20 August 1930 the joining of the arches was celebrated by flying the flags of Australia and the United Kingdom from the jibs of the creeper cranes.[42][45]

Once the arch was completed, the creeper cranes were then worked back down the arches, allowing the roadway and other parts of the bridge to be constructed from the centre out. The vertical hangers were attached to the arch, and these were then joined with horizontal crossbeams. The deck for the roadway and railway were built on top of the crossbeams, with the deck itself being completed by June 1931, and the creeper cranes were dismantled. Rails for trains and trams were laid, and road was surfaced using concrete topped with asphalt.[42] Power and telephone lines, and water, gas, and drainage pipes were also all added to the bridge in 1931.[citation needed]

The pylons were built atop the abutment towers, with construction advancing rapidly from July 1931. Carpenters built wooden scaffolding, with concreters and masons then setting the masonry and pouring the concrete behind it. Gangers built the steelwork in the towers, while day labourers manually cleaned the granite with wire brushes. The last stone of the north-west pylon was set in place on 15 January 1932, and the timber towers used to support the cranes were removed.[19][42]

On 19 January 1932, the first test train, a steam locomotive, safely crossed the bridge.[46] Load testing of the bridge took place in February 1932, with the four rail tracks being loaded with as many as 96 New South Wales Government Railways steam locomotives positioned end-to-end.[47] The bridge underwent testing for three weeks, after which it was declared safe and ready to be opened.[42] The first trial run of an electric train over the bridge was successfully completed on both lines 11 March 1932.[48] On 19 March 1932, 632 people were the first fare-paying passengers to cross the bridge by rail, paying a premium of 10 s. for the privilege, but they were not the first members of the public to do so. That distinction fell to a pair of clergymen who inadvertently boarded the test train of the previous day, and were discovered too late to be ejected.[49] The construction worksheds were demolished after the bridge was completed, and the land that they were on is now occupied by Luna Park.[50]

The standards of industrial safety during construction were poor by today's standards. Sixteen workers died during construction,[51] but surprisingly only two from falling off the bridge. Several more were injured from unsafe working practices undertaken whilst heating and inserting its rivets, and the deafness experienced by many of the workers in later years was blamed on the project. Henri Mallard between 1930 and 1932 produced hundreds of stills[52] and film footage[53] which reveal at close quarters the bravery of the workers in tough Depression-era conditions.[citation needed]

Interviews were conducted between 1982-1989 with a variety of tradesmen who worked on the building of the bridge. Among the tradesmen interviewed were drillers, riveters, concrete packers, boilermakers, riggers, ironworkers, plasterers, stonemasons, an official photographer, sleepcutters, engineers and draughtsmen.[54]

The total financial cost of the bridge was AU£6.25 million, which was not paid off in full until 1988.[55]

Official opening ceremony

[edit]The bridge was formally opened on Saturday, 19 March 1932.[56] Among those who attended and gave speeches were the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Philip Game, and the Minister for Public Works, Lawrence Ennis. The Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang, was to open the bridge by cutting a ribbon at its southern end.[57]

However, just as Lang was about to cut the ribbon, a man in military uniform rode up on a horse, slashing the ribbon with his sword and opening the Sydney Harbour Bridge in the name of the people of New South Wales before the official ceremony began. He was promptly arrested.[58] The ribbon was hurriedly retied and Lang performed the official opening ceremony and Game thereafter inaugurated the name of the bridge as Sydney Harbour Bridge and the associated roadway as the Bradfield Highway. After they did so, there was a 21-gun salute and an Royal Australian Air Force flypast. The intruder was identified as Francis de Groot. He was convicted of offensive behaviour and fined £5 after a psychiatric test proved he was sane, but this verdict was reversed on appeal. De Groot then successfully sued the Commissioner of Police for wrongful arrest and was awarded an undisclosed out of court settlement. De Groot was a member of a right-wing paramilitary group called the New Guard, opposed to Lang's leftist policies and resentful of the fact that a member of the British royal family had not been asked to open the bridge.[58] De Groot was not a member of the regular army but his uniform allowed him to blend in with the real cavalry. This incident was one of several involving Lang and the New Guard during that year.[citation needed]

A similar ribbon-cutting ceremony on the bridge's northern side by North Sydney's mayor, Alderman Primrose, was carried out without incident. It was later discovered that Primrose was also a New Guard member but his role in and knowledge of the de Groot incident, if any, are unclear.[citation needed] The pair of golden scissors used in the ribbon cutting ceremonies on both sides of the bridge was also used to cut the ribbon at the dedication of the Bayonne Bridge, which had opened between Bayonne, New Jersey, and New York City the year before.[59][60]

Despite the bridge opening in the midst of the Great Depression, opening celebrations were organised by the Citizens of Sydney Organising Committee, an influential body of prominent men and politicians that formed in 1931 under the chairmanship of the lord mayor to oversee the festivities. The celebrations included an array of decorated floats, a procession of passenger ships sailing below the bridge, and a Venetian Carnival.[61] A message from a primary school in Tottenham, 515 km (320 mi) away in rural New South Wales, arrived at the bridge on the day and was presented at the opening ceremony. It had been carried all the way from Tottenham to the bridge by relays of school children, with the final relay being run by two children from the nearby Fort Street Boys' and Girls' schools. After the official ceremonies, the public was allowed to walk across the bridge on the deck, something that would not be repeated until the 50th anniversary celebrations.[30] Estimates suggest that between 300,000 and one million people took part in the opening festivities,[30] a phenomenal number given that the entire population of Sydney at the time was estimated to be 1,256,000.[62]

There had also been numerous preparatory arrangements. On 14 March 1932, three postage stamps were issued to commemorate the imminent opening of the bridge. Several songs were composed for the occasion.[63] In the year of the opening, there was a steep rise in babies being named Archie and Bridget in honour of the bridge.[64] One of three microphones used at the opening ceremony was signed by 10 local dignitaries who officiated at the event, Philip Game, John Lang, MA Davidson, Samuel Walder, D Clyne, H Primrose, Ben Howe, John Bradfield, Lawrence Ennis and Roland Kitson. It was supplied by Amalgamated Wireless Australasia, who organised the ceremony's broadcast and collected by Philip Geeves, the AWA announcer on the day. The radio is now in the collection of the Powerhouse Museum.[65]

The bridge itself was regarded as a triumph over Depression times, earning the nickname "the Iron Lung", as it kept many Depression-era workers employed.[66]

Operations

[edit]In 2010, the average daily traffic included 204 trains, 160,435 vehicles and 1650 bicycles.[67]

Road

[edit]

From the Sydney CBD side, motor vehicle access to the bridge is via Grosvenor Street, Clarence Street, Kent Street, the Cahill Expressway, or the Western Distributor. Drivers on the northern side will find themselves on the Warringah Freeway, though it is easy to turn off the freeway to drive westwards into North Sydney or eastwards to Neutral Bay and beyond upon arrival on the northern side.[citation needed]

The bridge originally only had four wider traffic lanes occupying the central space which now has six, as photos taken soon after the opening clearly show. In 1958 tram services across the bridge were withdrawn and the tracks replaced by two extra road lanes; these lanes are now the leftmost southbound lanes on the bridge and are separated from the other six road lanes by a median strip. Lanes 7 and 8 now connect the bridge to the elevated Cahill Expressway that carries traffic to the Eastern Distributor.

In 1988, work began to build a tunnel to complement the bridge. It was determined that the bridge could no longer support the increased traffic flow of the 1980s. The Sydney Harbour Tunnel was completed in August 1992 and carries only motor vehicles.

The Bradfield Highway is designated as a Travelling Stock Route[68] which means that it is permissible to herd livestock across the bridge, but only between midnight and dawn, and after giving notice of intention to do so. In practice, the last time livestock crossed the bridge was in 1999 for the Gelbvieh Cattle Congress.[69]

Tidal flow

[edit]The bridge is equipped for tidal flow operation, permitting the direction of traffic flow on the bridge to be altered to better suit the morning and evening peak hour traffic patterns.[70]

The bridge has eight lanes, numbered one to eight from west to east. Lanes three, four and five are reversible. One and two always flow north. Six, seven, and eight always flow south. The default is four each way. For the morning peak hour, the lane changes on the bridge also require changes to the Warringah Freeway, with its inner western reversible carriageway directing traffic to the bridge lane numbers three and four southbound. Until September 1982, during the evening peak the tidal flow was set as six northbound and two southbound lanes.[71]

The bridge has a series of overhead gantries which indicate the direction of flow for each traffic lane. A green arrow pointing down to a traffic lane means the lane is open. A flashing red "X" indicates the lane is closing, but is not yet in use for traffic travelling in the other direction. A static red "X" means the lane is in use for oncoming traffic. This arrangement was introduced in January 1986, replacing a slow operation where lane markers were manually moved to mark the centre median.[72]

It is possible to see odd arrangements of flow during night periods when maintenance occurs, which may involve completely closing some lanes. Normally this is done between midnight and dawn, because of the enormous traffic demands placed on the bridge outside these hours.[citation needed]

When the Sydney Harbour Tunnel opened in August 1992, lane 7 became a bus lane.[73][74]

Tolls

[edit]

The vehicular traffic lanes on the bridge are operated as a toll road. Since January 2009, there is a variable tolling system for all vehicles headed into the CBD (southbound). The toll paid is dependent on the time of day in which the vehicle passes through the toll plaza. The toll varies from a minimum value of $2.50 to a maximum value of $4.[75] There is no toll for northbound traffic (though taxis travelling north may charge passengers the toll in anticipation of the toll the taxi must pay on the return journey). In 2017, the Bradfield Highway northern toll plaza infrastructure was removed and replaced with new overhead gantries to service all southbound traffic.[76] Following on from this upgrade, in 2018 all southern toll plaza infrastructure was also removed.[77] Only the Cahill Expressway toll plaza infrastructure remains. The toll was originally placed on travel across the bridge, in both directions, to recoup the cost of its construction. This was paid off in 1988, but the toll has been kept (indeed increased) to recoup the costs of the Sydney Harbour Tunnel.[78][79]

Originally it cost a car or motorcycle six pence to cross, a horse and rider being three pence. Use of the bridge by bicycle riders (provided that they use the cycleway) and by pedestrians is free. Later governments capped the fee for motorcycles at one-quarter of the passenger-vehicle cost, but now it is again the same as the cost for a passenger vehicle, although quarterly flat-fee passes are available which are much cheaper for frequent users.[80] Originally there were six toll booths at the southern end of the bridge, these were replaced by 16 booths in 1950.[81] The toll was charged in both directions until 4 July 1970 when changed to only be applied to southbound traffic.[82][83]

After the decision to build the Sydney Harbour Tunnel was made in the early 1980s, the toll was increased (from 20 cents to $1, then to $1.50 in March 1989, and finally to $2 by the time the tunnel opened) to pay for its construction.[84] The tunnel also had an initial toll of $2 southbound. After the increase to $1, a concrete barrier on the bridge separating the Bradfield Highway from the Cahill Expressway was increased in height, because of the large numbers of drivers crossing it illegally from lane 6 to 7, to avoid the toll.

The southbound toll was increased to $2.20 in July 2000 to account for the newly imposed goods and services tax (GST).[85][86] The toll increased again to $3 in January 2002.[87]

In July 2008, a new electronic tolling system called e-TAG was introduced. The Sydney Harbour Tunnel was converted to this new tolling system while the Sydney Harbour Bridge itself had several cash lanes. The electronic system as of 12 January 2009 has now replaced all booths with E-tag lanes.[88] In January 2017 work commenced to remove the southern toll booths.[89] In August 2020, the remaining toll booths at Milsons Point were removed.[90][91] Tolls rose in October 2023 for the first time in 14 years.[92]

Pedestrians

[edit]The pedestrian-only footway is located on the east side of the bridge. Access from the northern side involves climbing an easily spotted flight of stairs, located on the east side of the bridge at Broughton Street, Kirribilli. Pedestrian access on the southern side is more complicated, but signposts in The Rocks area now direct pedestrians to the long and sheltered flight of stairs that leads to the bridge's southern end. These stairs are located near Gloucester Street and Cumberland Street.

The bridge can also be approached from the south by accessing Cahill Walk, which runs along the Cahill Expressway. Pedestrians can access this walkway from the east end of Circular Quay by a flight of stairs or a lift. Alternatively it can be accessed from the Botanic Gardens.[93]

Cyclists

[edit]

The bike-only cycleway is located on the western side of the bridge. Access from the northern side involves carrying or pushing a bicycle up a staircase, consisting of 55 steps, located on the western side of the bridge at Burton Street, Milsons Point. A wide smooth concrete strip in the centre of the stairs permits cycles to be wheeled up and down from the bridge deck whilst the rider is dismounted. A campaign to eliminate the steps on this popular cycling route to the CBD has been running since at least 2008.[94][95] On 7 December 2016 the NSW Roads Minister Duncan Gay confirmed that the northern stairway would be replaced with a A$20 million ramp alleviating the needs for cyclists to dismount. At the same time the NSW Government announced plans to upgrade the southern ramp at a projected cost of A$20 million. Both projects are expected to be completed by late 2020.[96][97][98] Access to the cycleway on the southern side is via the northern end of the Kent Street cycleway and/or Upper Fort Street in The Rocks.[99]

Rail

[edit]The bridge lies between Milsons Point and Wynyard railway stations, located on the north and south shores respectively, with two tracks running along the western side of the bridge. These tracks are part of the North Shore railway line.

In 1958, tram services across the bridge were withdrawn and the tracks they had used were removed and replaced by two extra road lanes; these lanes are now the leftmost southbound lanes on the bridge and are still clearly distinguishable from the other six road lanes. The original ramp that took the trams into a terminus at the underground Wynyard railway station is still visible at the southern end of the main walkway under lanes 7 and 8, although around 1964, the former tram tunnels and station were converted for use as a carpark for the Menzies Hotel and as public parking. One of the tunnels was converted for use as a storage facility after reportedly being used by the NSW police as a pistol firing range.[100]

Maintenance

[edit]

The Sydney Harbour Bridge requires constant inspections and other maintenance work to keep it safe for the public, and to protect from corrosion. Among the trades employed on the bridge are painters, ironworkers, boilermakers, fitters, electricians, plasterers, carpenters, plumbers, and riggers.[38]

The most noticeable maintenance work on the bridge involves painting. The steelwork of the bridge that needs to be painted is a combined 485,000 m2 (120 acres), the equivalent of sixty football fields. Each coat on the bridge requires some 30,000 L (6,600 imp gal) of paint.[38] A special fast-drying paint is used, so that any paint drops have dried before reaching the vehicles or bridge surface.[18] One notable identity from previous bridge-painting crews is Australian comedian and actor Paul Hogan, who worked as a bridge rigger before rising to media fame in the 1970s.[6]

In 2003 the Roads & Traffic Authority began completely repainting the southern approach spans of the bridge. This involved removing the old lead-based paint, and repainting the 90,000 m2 (22 acres) of steel below the deck. Workers operated from self-contained platforms below the deck, with each platform having an air extraction system to filter airborne particles. An abrasive blasting was used, with the lead waste collected and safely removed from the site for disposal.[38]

Between December 2006 and March 2010 the bridge was subject to works designed to ensure its longevity. The work included some strengthening.[101]

Since 2013, two grit-blasting robots specially developed with the University of Technology, Sydney have been employed to help with the paint stripping operation on the bridge.[102] The robots, nicknamed Rosie and Sandy,[103] are intended to reduce workers' potential exposure to dangerous lead paint and asbestos and the blasting equipment which has enough force to cut through clothes and skin.[104]

-

Stan Giddings, maintenance worker painting Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1945, by Alec Iverson

-

Maintenance crew painting the bridge

-

Bridge arch after strengthening, with some new steel outlined in red

Tourism

[edit]South-east pylon

[edit]

Even during its construction, the bridge was such a prominent feature of Sydney that it would attract tourist interest. One of the ongoing tourist attractions of the bridge has been the south-east pylon, which is accessed via the pedestrian walkway across the bridge, and then a climb to the top of the pylon of about 200 steps.[16]

Not long after the bridge's opening, commencing in 1934, Archer Whitford first converted this pylon into a tourist destination.[105] He installed a number of attractions, including a café, a camera obscura, an Aboriginal museum, a "Mother's Nook" where visitors could write letters, and a "pashometer". The main attraction was the viewing platform, where "charming attendants" assisted visitors to use the telescopes available,[105] and a copper cladding (still present) over the granite guard rails identified the suburbs and landmarks of Sydney at the time.[106]

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 saw tourist activities on the bridge cease, as the military took over the four pylons and modified them to include parapets and anti-aircraft guns.[107]

In 1948, Yvonne Rentoul opened the "All Australian Exhibition" in the pylon. This contained dioramas, and displays about Australian perspectives on subjects such as farming, sport, transport, mining, and the armed forces. An orientation table was installed at the viewing platform, along with a wall guide and binoculars. The owner kept several white cats in a rooftop cattery, which also served as an attraction, and there was a souvenir shop and postal outlet.[108] Rentoul's lease expired in 1971, and the pylon and its lookout remained closed to the public for over a decade.[109]

The pylon was reopened in 1982, with a new exhibition celebrating the bridge's 50th anniversary.[110] In 1987 a "Bicentennial Exhibition" was opened to mark the 200th anniversary of European settlement in Australia in 1988.[111]

The pylon was closed from April to November 2000 for the Roads & Traffic Authority and BridgeClimb to create a new exhibition called "Proud Arch". The exhibition focussed on Bradfield, and included a glass direction finder on the observation level, and various important heritage items.[112]

The pylon again closed for four weeks in 2003 for the installation of an exhibit called "Dangerous Works", highlighting the dangerous conditions experienced by the original construction workers on the bridge, and two stained glass feature windows in memory of the workers.[113]

BridgeClimb

[edit]

In the 1950s and 1960s, there were occasional newspaper reports of climbers who had made illegal arch traversals of the bridge by night. In 1973 Philippe Petit walked across a wire between the two pylons at the southern end of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Since 1998, BridgeClimb[114] has made it possible for tourists to legally climb the southern half of the bridge. Tours run throughout the day, from dawn to night, and are only cancelled for electrical storms or high wind.[115]

Groups of climbers are provided with protective clothing appropriate to the prevailing weather conditions, and are given an orientation briefing before climbing. During the climb, attendees are secured to the bridge by a wire lifeline. Each climb begins on the eastern side of the bridge and ascends to the top. At the summit, the group crosses to the western side of the arch for the descent. Each climb takes three-and-a-half-hours, including the preparations.[115]

In December 2006, BridgeClimb[114] launched an alternative to climbing the upper arches of the bridge. The Discovery Climb allows climbers to ascend the lower chord of the bridge and view its internal structure. From the apex of the lower chord, climbers ascend a staircase to a platform at the summit.[114]

Celebrations and protests

[edit]Since the opening, the bridge has been the focal point of much tourism, national pride and even protests[116]

50th Anniversary celebrations

[edit]In 1982, the 50th anniversary of the opening of the bridge was celebrated. For the first time since its opening in 1932, the bridge was closed to most vehicles with the exception of vintage vehicles, and pedestrians were allowed full access for the day.[13] The celebrations were attended by Edward Judge, who represented Dorman Long.[117][118]

Bicentennial Australia Day celebrations

[edit]Australia's bicentennial celebrations on 26 January 1988 attracted large crowds in the bridge's vicinity as merrymakers flocked to the foreshores to view the events on the harbour. The highlight was the biggest parade of sail ever held in Sydney, square-riggers from all over the world, surrounded by hundreds of smaller craft of every description, passing majestically under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The day's festivities culminated in a fireworks display in which the bridge was the focal point of the finale, with fireworks streaming from the arch and roadway. This was to become the pattern for later firework displays.[citation needed]

Sydney New Year's Eve

[edit]The Harbour Bridge has been an integral part of the Sydney New Year's Eve celebrations, generally being used in spectacular ways during the fireworks displays at 9pm and midnight. In recent times, the bridge has included a ropelight display on a framework in the centre of the eastern arch, which is used to complement the fireworks. The scaffolding and framework were clearly visible for some weeks before the event, revealing the outline of the design.

During the millennium celebrations in 2000, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was lit up with the word "Eternity", as a tribute to the legacy of Arthur Stace a Sydney artist who for many years inscribed said word on pavements in chalk in copperplate writing despite the fact that he was illiterate.[119]

The effects have been as follows:[120]

- NYE1997: Smiley face

- NYE1999: The word "Eternity" in copperplate writing[121]

- NYE2000: Rainbow Serpent and Federation Star

- NYE2001: Uluru, the Southern Cross and the Dove of Peace

- NYE2002: Dove of Peace and the word "PEACE"

- NYE2003: Light show

- NYE2004: "Fanfare"

- NYE2005: Three concentric hearts

- NYE2006: Coathanger and a diamond

- NYE2007: Mandala

- NYE2008: The Sun

- NYE2009: Taijitu Symbol, a Blue moon and a ring of fire

- NYE2010: Handprint, "X" Mark and a Spot

- NYE2011: Thought Bubble, Sun and Endless Rainbow

- NYE2012: Butterfly and a Lip

- NYE2013: Eye

- NYE2014: Light bulb

- NYE2015 onwards: Light shows

The numbers for the New Year's Eve countdown also appear on the eastern side of the Bridge pylons.[122]

Walk for Reconciliation

[edit]In May 2000, the bridge was closed to vehicular access for a day to allow a special reconciliation march—the "Walk for Reconciliation" – to take place. This was part of a response to an Aboriginal Stolen Generations inquiry, which found widespread suffering had taken place amongst Australian Aboriginal children forcibly placed into the care of white parents in a little-publicised state government scheme. Between 200,000 and 300,000 people were estimated to have walked the bridge in a symbolic gesture of crossing a divide.[123]

Sydney 2000 Olympics

[edit]During the Sydney 2000 Olympics in September and October 2000, the bridge was adorned with the Olympic Rings. It was included in the Olympic torch's route to the Olympic stadium. The men's and women's Olympic marathon events likewise included the bridge as part of their route to the Olympic stadium. A fireworks display at the end of the closing ceremony ended at the bridge. The east-facing side of the bridge has been used several times since as a framework from which to hang static fireworks, especially during the elaborate New Year's Eve displays.[124]

Formula One promotion

[edit]In 2005 Mark Webber drove a Williams-BMW Formula One car across the bridge.[125]

75th anniversary

[edit]

In 2007, the 75th anniversary of its opening was commemorated with an exhibition at the Museum of Sydney, called "Bridging Sydney".[126] An initiative of the Historic Houses Trust, the exhibition featured dramatic photographs and paintings with rare and previously unseen alternative bridge and tunnel proposals, plans and sketches.[127]

On 18 March 2007, the 75th anniversary of the Sydney Harbour Bridge was celebrated. The occasion was marked with a ribbon-cutting ceremony by the governor, Marie Bashir and the Premier of New South Wales, Morris Iemma. The bridge was subsequently open to the public to walk southward from Milsons Point or North Sydney. Several major roads, mainly in the CBD, were closed for the day. An Aboriginal smoking ceremony was held at 7:00pm.[128][129]

Approximately 250,000 people (50,000 more than were registered) took part in the event. Bright green souvenir caps were distributed to walkers. A series of speakers placed at intervals along the bridge formed a sound installation. Each group of speakers broadcast sound and music from a particular era (e.g. King Edward VIII's abdication speech; Gough Whitlam's speech at Parliament House in 1975), the overall effect being that the soundscape would "flow" through history as walkers proceeded along the bridge. A light-show began after sunset and continued late into the night, the bridge being bathed in constantly changing, multi-coloured lighting, designed to highlight structural features of the bridge. In the evening the bright yellow caps were replaced by orange caps with a small, bright LED attached. The bridge was closed to walkers at about 8:30pm.[citation needed]

Breakfast on the Bridge

[edit]On 25 October 2009 turf was laid across the eight lanes of bitumen, and 6,000 people celebrated a picnic on the bridge accompanied by live music.[130] The event was repeated in 2010.[131] Although originally scheduled again in 2011, this event was moved to Bondi Beach due to traffic concerns about the prolonged closing of the bridge.[132][133]

80th anniversary

[edit]On 19 March 2012, the 80th anniversary of the Sydney Harbour Bridge was celebrated with a picnic dedicated to the stories of people with personal connections to the bridge.[134] In addition, Google dedicated its Google Doodle on the 19th to the event.[135] The proposal to upgrade the bridge tolling equipment was announced by the NSW Roads Minister Duncan Gay.[136]

Protests

[edit]Various protests have caused disruptions on the Sydney Harbour Bridge. In 2019, Greenpeace activists scaled the bridge and they were arrested soon after.[137] In 2021, a number of truck and bus drivers clogged the bridge for a number of hours; they were protesting the COVID-19 lockdown.[138]

Violet Coco blocked one lane of traffic in 2022 as part of a climate change protest.[139]

Flags

[edit]

Historically the flags of Australia and New South Wales had been flown above the bridge with the Aboriginal flag flown for nineteen days a year.[140] In February 2022, Premier Dominic Perrottet announced that the Australian, New South Wales and the Aboriginal flags were to permanently fly with a third pole erected.[141][142] In July 2022, it was announced that the Aboriginal flag would replace the New South Wales flag, which was given a prominent location within the Macquarie Street East redevelopment, near the Royal Mint and Hyde Park Barracks.[143]

Quotations

[edit]

There the proud arch Colossus like bestride

Yon glittering streams and bound the strafing tide.— Prophetic observation of Sydney Cove by Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin, from his poem "Visit of Hope to Sydney Cove, near Botany Bay", (1789).

I open this bridge in the name of His Majesty the King and all the decent citizens of NSW.

— Francis de Groot "opening" the Sydney Harbour Bridge, (1932). His organisation, the New Guard, had resented the fact that King George V had not been asked to open the bridge.[144]

To get on in Australia, you must make two observations. Say, "You have the most beautiful bridge in the world" and "They tell me you trounced England again in the cricket." The first statement will be a lie. Sydney Bridge [sic] is big, utilitarian and the symbol of Australia, like the Statue of Liberty or the Eiffel Tower. But it is very ugly. No Australian will admit this.

...in a gesture of anomalous exhilaration, at the worst time of the depression Sydney opened its Harbour Bridge, one of the talismanic structures of the earth, and by far the most striking thing ever built in Australia. At that moment, I think, contemporary Sydney began, perhaps definitive Sydney.

— Jan Morris gives her own assessment of the bridge in her book Sydney, (1982)[146]

...you can see it from every corner of the city, creeping into frame from the oddest angles, like an uncle who wants to get into every snapshot. From a distance it has a kind of gallant restraint, majestic but not assertive, but up close it is all might. It soars above you, so high that you could pass a ten-storey building beneath it, and looks like the heaviest thing on earth. Everything that is in it – the stone blocks in its four towers, the latticework of girders, the metal plates, the six-million rivets (with heads like halved apples) – is the biggest of its type you have ever seen... This is a great bridge.

— American travel-writer Bill Bryson's impressions of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in his book Down Under (2000).[147]

Heritage listing

[edit]

At the time of construction and until recently, the bridge was the longest single span steel arch bridge in the world. The bridge, its pylons and its approaches are all important elements in townscape of areas both near and distant from it. The curved northern approach gives a grand sweeping entrance to the bridge with continually changing views of the bridge and harbour. The bridge has been an important factor in the pattern of growth of metropolitan Sydney, particularly in residential development in post World War II years. In the 1960s and 1970s the Central Business District had extended to the northern side of the bridge at North Sydney which has been due in part to the easy access provided by the bridge and also to the increasing traffic problems associated with the bridge.[148][149]

Sydney Harbour Bridge was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 25 June 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[149]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

The bridge is one of the most remarkable feats of bridge construction. At the time of construction and until recently it was the longest single span steel arch bridge in the world and is still in a general sense the largest.[148][149]

- Bradfield Park North (Sandstone Walls)

"The archaeological remains are demonstrative of an earlier phase of urban development within Milsons Point and the wider North Sydney precinct. The walls are physical evidence that a number of 19th century residences existed on the site which were resumed and demolished as part of the Sydney Harbour Bridge construction".[149][150][151]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

The bridge, its pylons and its approaches are all important elements in townscape of areas both near and distant from it. The curved northern approach gives a grand sweeping entrance to the bridge with continually changing views of the bridge and harbour.[148][149]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The bridge has been an important factor in the pattern of growth of metropolitan Sydney, particularly in residential development in post World War II years. In the 1960s and 1970s the Central Business District had extended to the northern side of the bridge at North Sydney which has been due in part to the easy access provided by the bridge and also to the increasing traffic problems associated with the bridge.[148][149]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

- Bradfield Park North (Sandstone Walls)

"The archaeological remains have some potential to yield information about the previous residential and commercial occupation of Milsons Point prior to the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge transport link".[149][150][151]

Engineering heritage award

[edit]

The bridge was listed as a National Engineering Landmark by Engineers Australia in 1988, as part of its Engineering Heritage Recognition Program.[152]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "7BridgesWalk.com.au". Bridge History. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge". Government of Australia. 14 August 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Dr J.J.C. Bradfield". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Olympic connections across the UK". BBC News. 19 January 2012. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ a b James Weirick (2007). "Radar Exhibition – Bridging Sydney". Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Sydney Harbour Bridge". culture.gov.au. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 20 September 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ "Widest Bridge". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Port Mann Bridge". Transportation Investment Corporation. British Columbia: Province of British Columbia. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

Once complete, the new 10-lane Port Mann Bridge will the second largest and longest cable-supported bridge in North America, and at 65 metres wide it will be the widest bridge in the world.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge Facts for Kids". Facts For Kids. 12 May 2016. Archived from the original on 27 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ "Sydney Bridge Information". October 2016. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ "The construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge". Year 9 NSW//History//Investigating History. Red Apple Education. 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- ^ a b "Bridge Facts". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bridge History". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ Sydney Harbour Bridge. Dorman, Long & Co. 1932. p. 13.

- ^ C. Mackaness, ed. (2007). Bridging Sydney. Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales.

- ^ a b "Sydney Harbour Bridge Info". Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Engineering Materials: Rivets". Sydney Harbour Bridge. NSW Government: Board of Studies. Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ a b "The Sydney Harbour Bridge". This is Australia.com.au. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ a b "South East Pylon History: 1922 – 1932". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Smiles, Sam (1998). Going modern and being British: 1910–1960. Intellect Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-871516-95-1.

- ^ a b Nisbet, Gary. "John Burnet & Son". Glasgow – City of Sculpture. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ "To make a bridge. Where did the granite of the Sydney Harbour Bridge come from?". Inside History Magazine. 19 April 2014. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Moruya History". Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Kandos Cement". Sydney Morning Herald. 19 March 1932. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ "Cement and the Bridge Part Played by Kandos Co". Lithgow Mercury. 7 March 1932. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ "Stands the Test Kandos Cement Used for Harbour Bridge". Trove. Mudgee Guardian. 19 May 1930. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ "Kandos a Great Industry". The Sydney Mail. 7 September 1927. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Lalor, Peter (2006) [2005]. The bridge. Allen & Unwin. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-74175-027-0.

- ^ "1942–1945 (WWII)" (PDF). The Pylon Lookout. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Archives In Brief 37 – A brief history of the Sydney Harbour Bridge". The State Archives. NSW Government. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ "A Short History of the Sydney Harbour Bridge" (PDF). Transport NSW. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Arthur, Ian (2001). Norman Selfe, Man of the North Shore. unpublished essay submitted for the North Shore History Prize. pp. 21–24. Cited in Freyne, Catherine (2009). "Selfe, Norman". Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Ellmoos and Murray (2015). "Building the Sydney Harbour Bridge | The Dictionary of Sydney". dictionaryofsydney.org. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "Design Tenders and Proposals". NSW Government. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ McCallum, Jake (8 July 2016). "Rare plans for the Sydney Harbour Bridge show how the iconic landmark could have looked". Hornsby Advocate. News Corp Australia. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ "THE BRIDGE DESIGNER AND HIS SECRETARY". Sydney Morning Herald. 28 February 1924. p. 10. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "International Woman Suffrage News". 5 December 1924. Retrieved 28 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d "Sydney Harbour Bridge repainting" (PDF). Roads & Traffic Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ "The Vote". 10 October 1924. Retrieved 28 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Wynyard Former Tram Tunnels". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Lalor, Peter (2006). The bridge : an epic story of an Australian icon - the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-74176-069-9. OCLC 86108534.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Six million rivets: The timeline". Sydney Harbour Bridge. NSW Government: Board of Studies. Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ North Shore Bridge Railway Gazette 5 October 1923 page 417

- ^ Nicholson, John (2001). Building the Sydney Harbour Bridge (Google books). Allen & Unwin. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-86508-258-5. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

There was one creeper crane on each side of the harbour.

- ^ The Sydney Harbour Bridge Railway Gazette 18 March 1932 page 433

- ^ "First Train to Cross the Bridge". Sydney Morning Herald. No. 29, 342. New South Wales, Australia. 20 January 1932. p. 14. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ 125th Anniversary Special] Roundhouse October 1980

- ^ "First Electric Train to Cross the Sydney Harbour Bridge". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 29, 387. New South Wales, Australia. 12 March 1932. p. 16. Retrieved 17 August 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Harbor Bridge". Daily Advertiser (Wagga Wagga). New South Wales, Australia. 22 March 1932. p. 2. Retrieved 16 August 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "About Luna Park - Amusement Park in Sydney | Luna Park Sydney". www.lunaparksydney.com. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ^ "AtlasDirect news". Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- ^ Henri Mallard (photographer); introduced by Max Dupain and Howard Tanner. "Building the Sydney Harbour Bridge". Melbourne: Sun Books in association with Australian Centre for Photography, 1976. ISBN 0-7251-0232-2

- ^ The Construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, film by Mallard, Henri.; Litchfield, Frank.[Sydney]: Institution of Engineers, Australia, Sydney Division, [1995].

- ^ "Richard Raxworthy - interviews, 1982-1989, with Sydney Harbour Bridge builders, relating experiences 1923-1932". State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge". sydney.com. Destination NSW. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ Wendy Lewis, Simon Balderstone and John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland Publishers. pp. 140–142. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- ^ "National Museum of Australia - Sydney Harbour Bridge opens". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ a b "On this day in history: Sydney Harbour Bridge opens". Australian Geographic. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Two States Open Bayonne Bridge, Forming Fifth Link". New York Times. 15 November 1931. p. 1. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "Hails Bridge at Sydney". New York Times. 18 March 1932. p. 43. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ New South Wales Government Printing Office (1932). Photographs of Opening of Sydney Harbour Bridge [picture]. Government Printing Office, Sydney. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "SYDNEY'S POPULATION". Singleton Argus. New South Wales, Australia. 9 May 1932. p. 1. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge - Bridge Ahoy!". Bridge Ahoy!. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge Trivia". National Film & Sound Archive. 6 March 2017. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ "Reiss (Reisz) carbon granule microphone used at Sydney Harbour Bridge opening". Powerhouse Museum. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Tomalin, Terry (26 September 2000). "View won't leave you speechless; Series: Out there; Summer Olympics: Sydney 2000". St Petersburg Times. No. South Pinellas Edition. St. Petersburg, FL. p. 7C.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge precinct". Roads & Maritime Services. 17 May 2017. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "NSW drovers rally to save historic travelling stock routes". The Wilderness Society. 27 August 2008. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Ellicott, John (3 March 2017). "Can't be done for Herd of Hope? Here's proof it can". The Land. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Managing the network". Roads & Maritime Services. 6 September 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Tidal Flow Operation on the Sydney Harbour Bridge Main Roads December 1983 page 109

- ^ Annual Report for year ended 30 June 1986] Department of Main Roads

- ^ Harbour Bridge Public Transport Lane Fleetline issue 198 January 1992 page 13

- ^ Opening of Sydney Harbour Tunnel & Gore Hill Freeway Australian Bus Panorama issue 8/3 October 1992 page 38

- ^ Toll costs by road Archived 4 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine Government of New South Wales

- ^ "Northern toll plaza precinct upgrade". Roads & Maritime Services. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ "Southern toll plaza precinct upgrade". Roads & Maritime Services. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ At Last! Sydney Harbour Bridge Paid For Daily Telegraph 25 July 1988 page 1

- ^ Don't we own the Bridge yet? The Daily Telegraph 15 June 2009

- ^ "Motorcyclists". Roads & Traffic Authority. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Sydney Harbour Bridge Truck & Bus Transportation March 1950 page 9

- ^ Introduction of One-Way Toll Collection on Sydney Harbour Bridge Main Roads September 1970 pages 24/25

- ^ Reaching the North Trolley Wire issue 200 June 1982 page 23

- ^ Annual report for year ended 30 June 1989] Roads & Traffic Authority

- ^ Sydney Harbour Bridge Tolling (PDF). Roads & Traffic Authority. March 2011. ISBN 9781921899126. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Walker, Frank; West, Andrew (1 July 2020). "From the Archives, 2000: PM Howard braves public's reaction to GST". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "The Sydney Harbour Bridge turns 90". University of Sydney. 18 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Sydney Harbour Bridge cashless tolling Roads & Traffic Authority

- ^ Southern toll plaza precinct upgrade Roads & Maritime Services 6 January 2017

- ^ Sydney Harbour Bridge toll booths to be removed Archived 16 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine Transport for NSW 15 June 2020

- ^ Northern toll plaza precinct upgrade Archived 7 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Roads & Maritime Services

- ^ Sydney Harbour Bridge and Tunnel tolls to rise Transport for NSW 23 September 2023

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge Walk". Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "HarbourLink". Sydneyharbourlink.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ HarbourLink – North Sydney Council Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McNally, Lucy (7 December 2016). "Sydney Harbour Bridge cyclists can expect $35 million bike ramp and upgrade by 2020". ABC News. Australia. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Stempien, Filip (7 December 2016). "New ramps and cycleways for Sydney Harbour Bridge". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ McNab, Heathery (8 August 2016). "Plan in the works to ramp up access to Sydney Harbour Bridge". Daily Telegraph. Australia. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Cycleway Finder". Roads & Maritime Services (Version 3 ed.). Government of New South Wales. 2016. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Hidden stairs revealed at Wynyard Station after more than 50 years". Commercial Property & Real Estate News. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge Upgrade" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ Wendy Frew (18 July 2013). "Spick and span". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Bryant, Chris (5 June 2014). "Dawn of a robot revolution as army of machines escape the factory". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "Grit-blasting robots clean Sydney Harbour Bridge". bbc.co.uk. 18 July 2013. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Southeast Pylon History: 1934". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Glass View Finder". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Southeast Pylon History: 1939 – 1945". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Southeast Pylon History: 1948". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Southeast Pylon History: 1971". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Southeast Pylon History: 1982". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Southeast Pylon History: 1987". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Southeast Pylon History: 2000". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Southeast Pylon History: 2003". Pylon Lookout: Sydney Harbour Bridge. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ a b c "BridgeClimb". BridgeClimb. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ a b "BridgeClimb - Pre-Climb Checklist". BridgeClimb Sydney. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ "Department of the Environment and Energy". Department of the Environment and Energy. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Reid, Carlton (2017). Bike Boom. doi:10.5822/978-1-61091-817-6. ISBN 978-1-61091-872-5. S2CID 159268848. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge". bestbridge.net. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ "New Years Eve fireworks on the Sydney Harbour Bridge and Eternity, 1999". City of Sydney Archives. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "World atlas of street art and graffiti". Choice Reviews Online. 51 (7): 51–3581. 2014. ISSN 0009-4978. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Dennis, Anthony (1 January 2000). "Millennium dawns". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge". bestbridge.net. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Marching for a fresh beginning". Sydney Morning Herald. 28 May 2010. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour - New Year's Eve Fireworks". sydney.com. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "NSW: F1 driver Mark Webber to hoon across the Harbour Bridge". 18 February 2005. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ Bridging Sydney Historic Houses Trust, New South Wales

- ^ "Bridging Sydney". Sydney Living Museums. 17 January 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. "Cap marking 75th anniversary of Sydney Harbour Bridge". Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, Australia. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "REUTERS". 18 March 2007. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Harbour Bridge picnic may become annual". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ "Breakfast on the Bridge". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ "Breakfast on the Bridge". 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 28 December 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ "Breakfast moves from bridge to beach". 15 October 2011. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge 80th Birthday". Roads & Traffic Authority. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012.

- ^ "Google doodles for Sydney Harbour Bridge 80th birthday". Mumbrella. 18 March 2012. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ "Harbour Bridge celebrates 80th birthday". The Age. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ "Police arrest 15 after Greenpeace activists dangle from Harbour Bridge". ABC News. 13 May 2019. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Truckies block bridges in protest of NSW Covid-19 restrictions". 17 July 2021. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Gladstone, Nigel; Carmody, Broede (2 December 2022). "As it happened: Labor's industrial relations reforms pass the Senate; Liberals to finalise Voice to parliament position next year". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ Rabe, Tom (18 June 2022). "Aboriginal flag to fly permanently atop Harbour Bridge by end of year". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Meacham, Savannah (5 February 2022). "Aboriginal flag Sydney Harbour Bridge: NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet says flag will fly permanently over landmark". Nine.com.au. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Aboriginal flag will fly high and proud on Sydney Harbour Bridge". The New Daily. 5 February 2022. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Rabe, Tom (10 July 2022). "Aboriginal flag to permanently replace NSW flag atop Sydney Harbour Bridge". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "JJC Bradfield and JT Lang: the movers and shakers". Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Michener, James, Return to Paradise, (1951), Corgi Books:London, page 275

- ^ Morris, Jan, Sydney (1982), Faber & Faber, London. Page 24

- ^ Bryson, Bill (2000). Down Under. Transworld. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-552-99703-X.

- ^ a b c d Walker and Kerr, 1974.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Sydney Harbour Bridge, approaches and viaducts (road and rail)". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00781. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ a b Statement of Heritage Impact - Sandstone Walls: Bradfield Park North, Milsons Point (2003: 8)

- ^ a b McFadyen and Stuart, HLA Envirosciences

- ^ "Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1932-". Engineers Australia. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Sydney Harbour Bridge, approaches and viaducts (road and rail)".

- BridgeClimb (2007). "BridgeClimb".

- Di Fazio, B. (2001). Bradfield Park North, Milsons Point Archaeological Assessment.

- Douglas, Peter (2005). Archaeological Management of Proposed Development of Bradfield Park Plaza, Bradfield Park South at Milsons Point NSW.

- Four papers on the design and construction of the bridge in volume 238 of the Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, 1935 Kinley

- GHD Transportation Consultants Pty Ltd (1982). Environmental Impact Statement for ninth lane and fottway on Sydney Harbour Bridge Sydney NSW.

- Hughes, Nathanael (Photographer) (2015). Archival Photographic Recording of Bay 9, Middlemiss Street, Lavender Bay, NSW.

- Knezevic, Daniel,(1947), "The Lost Bridge"

- McFadyen, K.; Stuart, I.; HLA Envirosciences (2003). Statement of Heritage Impact - Sandstone Walls: Bradfield Park North, Milsons Point.

- O'Brien, Geraldine (25 August 2003). "Men of steel who built the bridge with hard yakka". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Russell, Meaghan; McFadyen, Kylie; HLA Envirosciences (2003). Section 65A Research Design: Cesspit or Well, Bradfield Park North, Milsons Point.

- Ryan, Peter; Percival, Daniel (2005). Bradfield Park Lightning Pit: Photographic recording of Heritage Items (August 2005).

- RTA oral history program (2007). SydneyHarbourbridge celebrating 75 years / [electronic resource].

- Tourism NSW (2007). "Sydney Harbour Bridge Pylon Lookout".

- Walker and Kerr (1974). National Trust Classification Card - Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Attribution

[edit]![]() This Wikipedia article contains material from Sydney Harbour Bridge, approaches and viaducts (road and rail), entry number 781 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Sydney Harbour Bridge, approaches and viaducts (road and rail), entry number 781 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

External links

[edit]- Sydney Harbour Bridge at Structurae

- Sydney City Council

- "Sydney Harbour Bridge". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 8 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]. Features 'Sydney Harbour Bridge' by Jim Poe, 2014 and 'Building the Sydney Harbour Bridge' by Laila Ellmoos and Lisa Murray, 2015, with images.

- BridgeClimb

- Sydney Harbour Bridge turns 75 – Feature from Daily Telegraph

- Men at work: Sydney's Harbour Bridge – Australian Geographic Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- 75th Anniversary Celebrations Archived 31 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- NSW Bike Plan – Bicycle Information for New South Wales

- Sydney Harbour Bridge Archived 26 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine – News and Events