Nadi (yoga)

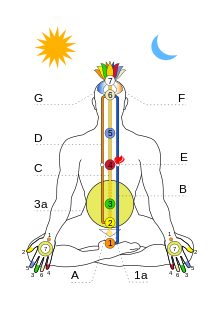

Nāḍī (Sanskrit: नाड़ी, lit. 'tube, pipe, nerve, blood vessel, pulse') is a term for the channels through which, in traditional Indian medicine and spiritual theory, the energies such as prana of the physical body, the subtle body and the causal body are said to flow. Within this philosophical framework, the nadis are said to connect at special points of intensity, the chakras.[1] All nadis are said to originate from one of two centres; the heart and the kanda, the latter being an egg-shaped bulb in the pelvic area, just below the navel.[1] The three principal nadis run from the base of the spine to the head, and are the ida on the left, the sushumna in the centre, and the pingala on the right. Ultimately the goal is to unblock these nadis to bring liberation.

Overview

[edit]Nadi is an important concept in Hindu philosophy, mentioned and described in the sources, some as much as 3,000 years old. The number of nadis of the human body is claimed to be up to hundreds-of-thousands and even millions. The Shiva Samhita treatise on yoga states, for example, that out of 350,000 nadis 14 are particularly important, and among them, the three just mentioned are the three most vital.[1] The three principal nadis are ida, pingala, and sushumna.[2] Ida (इडा, iḍā "comfort") lies to the left of the spine, whereas pingala (पिङ्गल, piṅgala "orange", "tawny", "golden", "solar") is to the right side of the spine, mirroring the ida. Sushumna (Suṣumṇa "very gracious", "kind"[3]) runs along the spinal cord in the center, through the seven chakras. When the channels are unblocked by the action of yoga, the energy of kundalini uncoils and rises up the sushumna from the base of the spine.[2] While the sushumna came to be envisioned as a vertical channel extending upwards from the heart, navel region, or base of the torso, there is an old precedent for the idea that it extends, like the śaktitantu, to the feet: the Mataṅgapārameśvara, a comparatively early Siddhāntatantra, envisions the sushumna running from the tips of the big toes to the crown of the head via the navel and heart. This archaic model of a central channel extending to the feet, linking together the principal series of nine lotuses [i.e., Kapālīśabhairava, the four Devīs and the four Dūtīs] spanning the body’s axis from crest (śikhā) to feet (pāda), may underlie the Brahmayāmala’s conception of the śaktitantu.

The nadis play a role in yoga, as many yogic practices, including shatkarmas, mudras and pranayama, are intended to open and unblock the nadis. The ultimate aim of some yogic practices are to direct prana into the sushumna nadi specifically, enabling kundalini to rise, and thus bring about moksha, or liberation.[4]

Early references

[edit]

"The nāḍis penetrate the body from the soles of the feet to the crown of the head. In them is prāṇa, the breath of life and in that life abides Ātman, which is the abode of Shakti, creatrix of the animate and inanimate worlds." (VU 54/5)[6]

Several of the ancient Upanishads use the concept of nadis (channels). The nadi system is mentioned in the Chandogya Upanishad (8~6 cc. BCE), verse 8.6.6.[7] and in verses 3.6–3.7 of the Prasna Upanishad (second half of the 1 millennium BCE). As stated in the last,

3.6 "In the heart verily is Jivātma. Here a hundred and one nāḍis arise. For each of these nāḍis there are one hundred nāḍikās. For each of these there are thousands more. In these Vyâna moves."

3.7 "Through one of these, the Udâna leads us upward by virtue of good deeds to the good worlds, by sin to the sinful worlds, by both to the worlds of men indeed." (PU Q3)[8][9]

The medieval Sat-Cakra-Nirupana (1520s), one of the later and more fully developed classical texts on nadis and chakras, refers to these three main nadis by the names Sasi, Mihira, and Susumna.[10]

In the space outside the Meru, the right apart from the body placed on the left and the right, are the two nadis, Sasi and Mihira. The Nadi Susumna, whose substance is the threefold Gunas, is in the middle. She is the form of Moon, Sun, and Fire even water also; Her body, a string of blooming Dhatura flowers, extends from the middle of the Kanda to the Head, and the Vajra inside Her extends, shining, from the Medhra to the Head.[11]

Functions and activities

[edit]In hatha yoga theory, nadis carry prana, life force energy. In the physical body, the nadis are channels carrying air, water, nutrients, blood and other bodily fluids around and are similar to the arteries, veins, capillaries, bronchioles, nerves, lymph canals and so on.[1] In the subtle and the causal body, the nadis are channels for so-called cosmic, vital, seminal, mental, intellectual, etc. energies (collectively described as prana) and are important for sensations, consciousness and the spiritual aura.[1]

Yoga texts disagree on the number of nadis in the human body. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika and Goraksha Samhita quote 72,000 nadis, each branching off into another 72,000 nadis, whereas the Shiva Samhita states 350,000 nadis arise from the navel center,[1] and the Katha Upanishad (6.16) says that 101 channels radiate from the heart.[2]

The Ida and Pingala nadis are sometimes in modern readings interpreted as the two hemispheres of the brain. Pingala is the extroverted (Active), solar nadi, and corresponds to the right side of the body and the left side of the brain. Ida is the introverted, lunar nadi, and corresponds to the left side of the body and the right side of the brain.[12]

Three channels (nadis)

[edit]

Central channel (Sushumna)

[edit]Sushumna is the central and most important channel. It connects the base chakra to the crown chakra. It is important in Yoga and Tantra.[13][14] It corresponds to the river Saraswati.

Side channels

[edit]Left channel (Ida)

[edit]Ida is associated with lunar energy. The word ida means "comfort" in Sanskrit. Idā has a moonlike nature and feminine energy with a cooling effect.[15] It courses from the left testicle to the left nostril and corresponds to the Ganges river.

Right channel (Pingala)

[edit]Pingala is associated with solar energy. The word pingala means "orange" or "tawny" in Sanskrit. Pingala has a sunlike nature and masculine energy.[15] Its temperature is heating and courses from the right testicle to the right nostril. It corresponds to the river Yamuna.

Unblocking the channels

[edit]

The purpose of yoga is moksha, liberation and hence immortality in the state of samadhi, union, which is the meaning of "yoga" as described in the Patanjalayayogasastra.[16][17] This is obstructed by blockages in the nadis, which allow the vital air, prana, to languish in the Ida and Pingala channels. The unblocking of the channels is therefore a vital function of yoga.[17] The various practices of yoga, including the preliminary purifications or satkarmas, the yogic seals or mudras, visualisation, breath restraint or pranayama, and the repetition of mantras work together to force the prana to move from the Ida and Pingala into the central Sushumna channel.[17] The mudras in particular close off various openings, thus trapping prana and directing it towards the Sushumna. This allows kundalini to rise up the Sushumna channel, leading to liberation.[17][18][19]

Other traditions and interpretations

[edit]Other cultures work with concepts similar to nadis and prana.

Chinese

[edit]Systems based on Traditional Chinese Medicine work with an energy concept called qi, analogous to prana.[20] Qi travels through meridians analogous to the nadis. The microcosmic orbit practice has many similarities to certain Indian nadi shuddha (channel clearing) exercises and the practice of Kriya Yoga.

Tibetan

[edit]Tibetan medicine borrows many concepts from Yoga through the influence of Tantric Buddhism. One of the Six Yogas of Naropa is a cleansing of the central channel called phowa, enabling the transfer of consciousness to a pure land through the sagittal suture.[21]

The Vajrayana practice of Trul Khor is another practice used to direct and control the flow of energy within the body's energetic meridians through breath control and physical postures.[22]

European

[edit]Sometimes the three main nadis are related to the Caduceus of Hermes: "the two snakes of which symbolize the kundalini or serpent-fire which is presently to be set in motion along those channels, while the wings typify the power of conscious flight through higher planes which the development of that fire confers".[23]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f B. K. S. Iyengar (2010). Light on Pranayama. the Crossroad Publishing Company. pp. Chapter 5: Nadis and Chakras.

- ^ a b c Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 172–173.

- ^ spokensanskrit.de

- ^ a b Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. Chapter 6, especially pages 228–229.

- ^ Varaha Upanishad, c. 1200–1600 CE

- ^ Varahopanisad V, 54/5.

- ^ For reference to Chandogya Upanishad 8.6.6 and interpretation as an early form of the occult physiology see: McEvilley, Thomas. "The Spinal Serpent", in: Harper and Brown, p. 94.

- ^ Nāḍikās are small nadis.

Udâna are often translated as "out-breathing" in this context. Perhaps a metaphor for death. - ^ Prasna Upanishad, Question 3 § 6, 7.

- ^ Sat-Cakra-Nirupana, Purnananda Swami

- ^ Sat-Cakra-Narupana, The Muladhara Cakra, transl. Sir John Woodroffe in The Serpent Power: Being the Ṣaṭ-cakra-nirūpana and Pādukā-pañcaka

- ^ "Nadis". Yoga Dharma. 5 October 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 122, 173, 178, 187, 190, 194, 197, 202.

- ^ Samuel, Geoffrey (2010). The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 255, 271.

- ^ a b Three fundamental nadis

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 4–6, 323.

- ^ a b c d Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 178–181.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 228–233.

- ^ Arthur Avalon, The Serpentine Power (collection of yoga-tantric texts)

- ^ Hankey, Alex; Nagendra, HR; Nagilla, Niharika (2013). "Effects of yoga practice on acumeridian energies: Variance reduction implies benefits for regulation". International Journal of Yoga. 6 (1). Medknow: 61–65. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.105948. ISSN 0973-6131. PMC 3573545. PMID 23439630.

- ^ Georgios, Halkias (October 2019). "Ascending to Heaven after Death: Karma Chags med's Commentary on Mind Transference" (PDF). Revue d'Études Tibétaines (52): 70–89.

- ^ Chaoul, M. Alejandro (October 2003). "Yogic practices in the Bon tradition" (PDF). Wellcome History (24): 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-29. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ C. W. Leadbeater, Chakras, Adyar, 1929

Sources

[edit]- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.

- Sandra, Anderson (2018). "The Nadis: Tantric Anatomy of the Subtle Body". Himalayan Institute. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- "The Three Main Nadis: Ida, Pingala and Sushumna". Hridaya Yoga France. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- "The Ida and Pingala". Yin Yoga. Retrieved 2021-04-03.