Surkotada

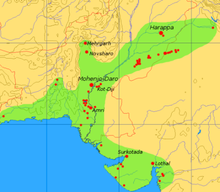

Surkotada is an archaeological site located in Rapar Taluka of Kutch district, Gujarat, India which belongs to the Indus Valley civilisation (IVC).[1][2] It is a smaller fortified IVC site with 1.4 hectares (3.5 acres) in area.[3]: 220

Location and environment

[edit]The site at Surkotada is located 160 km (99 mi) north-east of Bhuj, in the district of Kutch, Gujarat. The ancient mound stands surrounded by an undulating rising ground clustered by small sandstone hills. These hills are covered with red laterite soil giving the entire region a reddish-brown colour. The vegetation is scarce and consists of cactus, small babul and pilu trees and thorny shrubs. These give green patches to the red environment. The mound was discovered in 1964 by J. P. Joshi of the Archaeological Survey of India. The mound is higher on the western side and lower on the eastern side and has an average height of 5 to 8 m (16 to 26 ft). In the ancient days, a river 750 m (½ mi) wide flowed past the north-eastern side of the site. This river, which emptied into the Little Rann, might have been an important reason for siting the town here. Now this river is only a small nalla (stream).

Chronology

[edit]The chronology of the occupation of the site at Surkotada is not the same as other Harappan / Indus Valley civilization sites. The dates from Surkotada are later than most Harappan sites but conform well with the occupational dates from Lothal and Kalibangan. In other words, the Harappans did not establish a settlement in Surkotada in the earliest phase of Harappan maturity but did so almost towards the end. The site of Surkotada was occupied for a period of 400 years with no breaks or desertions. Archaeologists have divided the history of settlement in Surkotada into three cultural phases. The following is a description of the three phases in terms of the building activity:

Period IA (2100 BC – 1950 BC)

[edit]The earliest occupants of Surkotada had affiliations with an antecedent culture. They built a citadel with mud-brick and mud-lump fortification with a rubble veneer of five to eight courses over a raised platform of hard rammed yellow earth. The platform had an average height of 1.5 m (4.9 ft) and the average base width of the fortification wall was 7 m (23 ft). The bricks used were in the ratio 1:2:4 which conforms with mature Harappan standards. The height of this wall was 4.5 m (15 ft). The residential area was also built with a fortification wall having a thickness of 3.5 m (11 ft). The citadel had two entrances one on the southern side and one on the eastern side for accessing the residential area. In the residential area a drain, a bathroom with a small platform and a soakage jar in every house prove the well known sanitary arrangement and drainage system of the Harappan

Period IB (1950 BC – 1800 BC) There is no break in the continuity of settlement from phase IA to phase IB, but this period has been defined separately due to the arrival of a new wave of people who used a new form of pottery and instruments. They retained the structure of the citadel but added a mud brick reinforcement to the inside of the fortification wall. As this would have only reduced the area within the citadel, it is not clear why they did this. The end of period IB is marked by a thick layer of ash which represents a widespread conflagration.

Period IC (1800 BC – 1700 BC)

[edit]After the fire of period IB, a new group of people came to Surkotada though the site does not show any break in the continuity of settlement. The new people followed their predecessors in the layout of the settlement and made a citadel and a residential complex on the same lines made of rubble and dressed stones. These measured respectively

Layout of the city and architectural remains

[edit]The total built up area of Surkotada of the period IC is in the form of a rectangle aligned along the cardinal directions. It measures 120 m (390 ft) east-west and about 60 m (200 ft) north-south. Despite its small size, archaeologists consider Surkotada very important. It had been treated by its builders at par with Kalibangan and Lothal in terms of planning. The gates of Surkotada have also been treated with care and in some respects are different from general Harappan trends. Moreover, many scholars feel that the location of Surkotada was strategic to control the eastward migration of the Harappans from Sind. Surkotada also supports the concept of the feudal system of administration in the civilization . In other words, Surkotada could have functioned as a regional capital or garrison town.

The plan of Surkotada is composed of two squares - the one to the east is called the residential complex and measures 60 by 55 m (197 by 180 ft) while the one on the west is the citadel and it measures 60 by 60 m (200 by 200 ft). The citadel is the higher of the two. The fortification wall of the citadel has an average base width of 3.5–4 m (11–13 ft) and has two 10 by 10 m (33 by 33 ft) bastions on the southern wall. Similar bastions are expected on the northern wall but have not been excavated yet.

On the southern wall of the citadel there is a centrally placed gateway projecting out. This gateway measure 10 by 23 m (33 by 75 ft) and has steps and a ramp leading up to the main entrance which has two guard rooms. There is a 1.7 m (5+1⁄2 ft) wide passage leading into the entrance. The citadel consists of large houses some of which have up to nine rooms each. From the citadel there is an entrance in the east wall, again 1.7 m (5+1⁄2 ft) wide, for access to the residential complex.

The residential area consists of houses which are the smaller than the citadel houses. A typical example is a house with five interconnected rooms, a courtyard closed on three sides and a platform outside facing the street. The platform would have been used for transactions and as a shop. The southern fortification wall of the residential area also has an entrance which has received a different treatment by its builders. It differs from other Harappan gates in the sense that it is a straight entrance and not a staggered or bent one. The gate itself is set in the thickness of the fortification wall while there are two guard rooms projecting out. The fortification wall of the residential complex has an average thickness of 3.4 m (11 ft) and has bastions at the corners which are smaller than the ones on the citadel fortification wall.

All these features show mature Harappan traits even up to 1700 BC which chronologically is quite remarkable. Mature Harappan principles were being followed in Surkotada long after the civilization itself had started declining and most other sites had decayed or died out.

As of today there is no evidence of a city scale settlement near the citadel complex of Surkotada, as one might be expected on the lines of Mohenjo-daro and Kalibangan. About 500 m (1,600 ft) south-east of the citadel, there is a low mound which represents some sort of small habitation but the Harappan vestiges are scarce. Archaeologists feel that the possibility of the existence of a large settlement is remote but cannot be ruled out.

Horse remains

[edit]During 1974, the Archaeological Survey of India undertook excavations in this site. J. P. Joshi and A. K. Sharma reported findings of bones at all levels (circa 2100-1700 BCE), which they described as horse bones.[4][5] Sándor Bökönyi (1997), on examining the bone samples found at Surkotada, opined that at least six samples probably belonged to true horse.[1][2][6]

However, archeologists Richard H. Meadow and Ajita Patel disagree, on the grounds that the remains of the Equus ferus caballus horse are difficult to distinguish from other equid species such as Equus asinus (donkeys) or Equus hemionus (onagers).[2][7][8][note 1]

Other significant finds

[edit]Presence of Mongooses were found in Surkotada as well as in Mohenjadaro, Harappa, and Rangpur, indicating that these animals were kept as a protection against snakes. Elephant bones and wolf bones (tamed?) were also found at Surkotada.[3]: 130–131

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Indigenous Aryanist point to isolated finds and interpretations to argue for the presence of horses in the IVC:[9] according to the Ministry of Culture of India, an animal figurine from Lothal, dated to the 3rd millennium BCE, is a horse head;[10] according to Erwin Neumayer, the Daimabad "chariot" had "a yoke fit for the neck of horses rather then [sic] cattle";[11][a] copper vehicle models of carts with animals with arched neck were interpreted in 1970 by Stuart Piggott as of horses. [12]

- Subnotes

- ^ Archaeologists are not unanimous about the date of these sculptures. On the basis of the circumstantial evidence, M. N. Deshpande, S. R. Rao and S. A. Sali are of view that these objects belong to the Late Harappan period. But on the basis of analysis of the elemental composition of these artifacts, D. P. Agarwal concluded that these objects may belong to the historical period. His conclusion is based on the fact these objects contain more than 10% Arsenic, while no Arsenical alloying has been found in any other Chalcolithic artifacts.Dhavalikar, M. K. (1982). Daimabad Bronzes (PDF). in Gregory L. Possehl. ed. Harappan Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. pp. 361–66. ISBN 0-85668-211-X.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bökönyi, Sándor (1997), "Horse remains from the prehistoric site of Surkotada, Kutch, late 3rd millennium B.C.", South Asian Studies, 13 (1): 297, doi:10.1080/02666030.1997.9628544

- ^ a b c Meadow, Richard H.; Patel, Adjita (1997). "A Comment on "Horse Remains from Surkotada" by Sándor Bökönyi". South Asian Studies. 13 (1): 308–315. doi:10.1080/02666030.1997.9628545. ISSN 0266-6030.

- ^ a b Jane McIntosh (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- ^ Archaeological Survey of India. Indian Archaeology 1974-75.

- ^ Bryant, Edwin (6 September 2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press. pp. 172–. ISBN 978-0-19-803151-2.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 158. ISBN 9788131711200.

- ^ Bryant 2001, pp. 169–175.

- ^ Sharma, Ram Sharan (1999). Ancient India. New Delhi: NCERT. p. 60.

- ^ Bryant 2001.

- ^ "Horse Head". Museums of India. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Chariots in the Chalcolithic Rock Art of Indian A Slide Show, Neumayer Erwin

- ^ Piggott, Stuart (1970). "Copper Vehicle-Models in the Indus Civilization". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 102 (2): 200–202. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00128394. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25203212.