Super Science Stories

Super Science Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine published by Popular Publications from 1940 to 1943, and again from 1949 to 1951. Popular launched it under their Fictioneers imprint, which they used for magazines, paying writers less than one cent per word. Frederik Pohl was hired in late 1939, at 19 years old, to edit the magazine; he also edited Astonishing Stories, a companion science fiction publication. Pohl left in mid-1941 and Super Science Stories was given to Alden H. Norton to edit; a few months later Norton rehired Pohl as an assistant. Popular gave Pohl a very low budget, so most manuscripts submitted to Super Science Stories had already been rejected by the higher-paying magazines. This made it difficult to acquire good fiction, but Pohl was able to acquire stories for the early issues from the Futurians, a group of young science fiction fans and aspiring writers.

Super Science Stories was an initial success, and within a year Popular increased Pohl's budget slightly, allowing him to pay a bonus rate on occasion. Pohl wrote many stories himself, to fill the magazine and to augment his salary. He managed to obtain stories by writers who subsequently became very well known, such as Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein. After Pohl entered the army in early 1943, wartime paper shortages led Popular to cease publication of Super Science Stories. The final issue of the first run was dated May of that year. In 1949 the title was revived with Ejler Jakobsson as editor; this version, which included many reprinted stories, lasted almost three years, with the last issue dated August 1951. A Canadian reprint edition of the first run included material from both Super Science Stories and Astonishing Stories; it was unusual in that it published some original fiction rather than just reprints. There were also Canadian and British reprint editions of the second incarnation of the magazine.

The magazine was never regarded as one of the leading titles of the genre, but has received qualified praise from science fiction critics and historians. Science fiction historian Raymond Thompson describes it as "one of the most interesting magazines to appear during the 1940s", despite the variable quality of the stories.[1] Critics Brian Stableford and Peter Nicholls comment that the magazine "had a greater importance to the history of sf than the quality of its stories would suggest; it was an important training ground".[2]

Publication history

[edit]Although science fiction (sf) had been published before the 1920s, it did not begin to coalesce into a separately marketed genre until the appearance in 1926 of Amazing Stories, a pulp magazine published by Hugo Gernsback. By the end of the 1930s the field was booming,[3] and several new sf magazines were launched in 1939.[4] Frederik Pohl, a science fiction fan and aspiring writer, visited Robert Erisman, the editor of Marvel Science Stories and Dynamic Science Stories, to ask for a job.[5] Erisman did not have an opening for him, but told Pohl that Popular Publications, a leading pulp publisher, was starting a new line of low-paying magazines and might be interested in adding a science fiction title.[6] On October 25, 1939, Pohl visited Rogers Terrill at Popular, and was hired immediately, at the age of nineteen,[7] on a salary of ten dollars per week.[8][notes 1] Pohl was given two magazines to edit: Super Science Stories and Astonishing Stories.[7][10] Super Science Stories was intended to carry longer pieces, and Astonishing focused on shorter fiction; Super Science Stories was retitled Super Science Novels Magazine in March 1941, reflecting this policy, but after only three issues the title was changed back to Super Science Stories.[1]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 2/1 | |||||||

| 1941 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | 3/1 | 3/2 | |||||||

| 1942 | 3/3 | 3/4 | 4/1 | 4/2 | ||||||||

| 1943 | 4/3 | 4/4 | ||||||||||

| Issues of the first run of Super Science Stories, showing volume/issue number. The colors identify the editors for each issue: Frederik Pohl until August 1941, and Alden H. Norton for the remaining issues. | ||||||||||||

Popular was uncertain of the sales potential for the two new titles and decided to publish them under its Fictioneers imprint, which was used for lower-paying magazines.[7][11] Super Science Stories' first issue was dated March 1940; it was bimonthly, with Astonishing Stories appearing in the alternate months.[5] In Pohl's memoirs he recalls Harry Steeger, one of the company owners, breaking down the budget for Astonishing for him: "Two hundred seventy-five dollars for stories. A hundred dollars for black and white art. Thirty dollars for a cover." For Super Science Stories, Steeger gave him an additional $50 as it was 16 pages longer, so his total budget was $455 per issue.[12] Pohl could only offer half a cent per word for fiction, well below the rates offered by the leading magazines.[7][13][notes 2] Super Science Stories sold well, despite Pohl's limited resources:[5] Popular was a major pulp publisher and had a strong distribution network, which helped circulation. Steeger soon increased Pohl's budget, to pay bonuses for popular stories.[5][notes 3] Pohl later commented that he was uncertain whether the additional funds really helped to bring in higher quality submissions, although at the time he assured Steeger it would improve the magazine.[16] Some of the additional money went to Ray Cummings, a long-established SF writer who came to see Pohl in person to submit his work. Cummings refused to sell for less than one cent a word; Pohl had some extra money available when Cummings first visited him. Though he disliked Cummings' work he was never able to bring himself to reject his submissions, or even to tell him that he could not really afford to pay the rate Cummings was asking. Pohl comments in his memoirs that "for months he [Cummings] would turn up regularly as clockwork and sell me a new story; I hated them all, and bought them all."[17]

By reducing the space he needed to fill with fiction, Pohl managed to stretch his budget. A long letter column took up several pages but required no payment, and neither did running advertisements for Popular's other magazines. Some authors sent inaccurate word counts with the stories they submitted, and savings were made by paying them on the basis of whichever word count was less—the author's or one done by Popular's staff. The result was a saving of forty to fifty dollars per issue. Snipped elements of black and white illustrations were also reused to fill space, as multiple uses of the same artwork did not require additional payments to the artist.[18]

Towards the end of 1940 Popular doubled Pohl's salary to twenty dollars per week.[8][notes 4] In June 1941 Pohl visited Steeger to ask for a further raise, intending to resign and work as a freelance writer if he was unsuccessful. Steeger was unreceptive, and Pohl commented later "I have never been sure whether I quit or got fired".[20][notes 5] Instead of replacing Pohl, Popular assigned editor-in-chief Alden H. Norton to add the magazines to his responsibilities. The arrangement lasted for seven months, after which Norton asked Pohl to return as his assistant.[5] Norton offered Pohl thirty-five dollars a week as an associate editor, substantially more than the twenty dollars a week he had received as editor, and Pohl readily accepted.[22][23]

Pohl was not eligible to be drafted for military service as he was married, but by the end of 1942 his marriage was over and he decided to enlist. As voluntary enlistment was suspended, he was unable to join the army immediately, but eventually was inducted on April 1, 1943.[24] Paper was difficult to obtain because of the war, and Popular decided to close the magazine down; the final issue, dated April 1943, was assembled with the assistance of Ejler Jakobsson.[25][26][notes 6]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 5/4 | 6/1 | |||||||

| 1950 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 6/4 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | ||||||

| 1951 | 7/4 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | ||||||||

| Issues of the second run of Super Science Stories, showing volume/issue number. Ejler Jakobsson was editor throughout. | ||||||||||||

In late 1948, as a second boom in science fiction publishing was beginning, Popular decided to revive the magazine.[1] Jakobsson later recalled hearing about the revival while on vacation, swimming in a lake, five miles from a phone: "A boy on a bicycle showed on shore and shouted, 'Call your office.'" When he reached a phone, Norton told him that the magazine was being relaunched and would be given to Jakobsson to edit. Damon Knight, who was working for Popular at the time, also worked on the magazine as assistant editor, although he was not credited.[25] The relaunched magazine survived for almost three years, but the market for pulps was weak, and when Knight left in 1950 to edit Worlds Beyond Jakobsson was unable to sustain support for it within Popular. It ceased publication with the August 1951 issue.[28]

Contents and reception

[edit]Because of the low rates of pay, for the most part, the stories submitted to Super Science Stories in its first year had already been rejected elsewhere. Pohl was a member of the Futurians, a group of science fiction fans that included Isaac Asimov, C.M. Kornbluth, Richard Wilson and Donald Wollheim; they were eager to become professional writers and were keen to submit stories to Pohl.[5] The Futurians were prolific; in Pohl's first year as an editor he bought a total of fifteen stories from them for the two magazines.[1] Pohl contributed material himself, usually in collaboration with one or more of the Futurians.[5] Particularly after his marriage to Doris Baumgardt in August 1940, Pohl realized that his salary covered their apartment rent with almost no money left over. He began to augment his income by selling his work to himself as well as to other magazines.[8] The first story Pohl ever published that was not a collaboration was "The Dweller in the Ice", which appeared in the January 1941 Super Science Stories.[29] All the stories Pohl bought from himself were published under pseudonyms; he used pseudonyms for everything he wrote until the 1950s.[30]

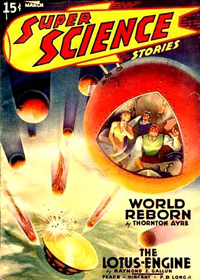

The first issue, dated March 1940, contained "Emergency Refueling", James Blish's first published story, two stories by John Russell Fearn (one under the pseudonym "Thornton Ayre"), fiction by Frank Belknap Long, Ross Rocklynne, Raymond Gallun, Harl Vincent and Dean O'Brien; and a poem by Kornbluth, "The Song of the Rocket", under the pseudonym "Gabriel Barclay".[31][32] Blish's most notable contribution to the magazine was "Sunken Universe", which appeared in the May 1942 issue under the pseudonym "Arthur Merlyn".[1] This later formed part of "Surface Tension", one of Blish's most popular stories.[1][32] Other writers whose first story appeared in Super Science Stories include Ray Bradbury, Chad Oliver, and Wilson Tucker.[7][33] Bradbury's first sale, "Pendulum", was bought by Norton, and appeared in the November 1941 issue;[7] Tucker's writing career began with "Interstellar Way Station" in May 1941,[31][33] and Oliver's "The Land of Lost Content" appeared in the November 1950 Super Science Stories.[1] Asimov appeared four times in Super Science Stories, starting with "Robbie", his first Robot story, under the title "Strange Playfellow".[34]

Although most stories submitted to Super Science Stories were rejects from the better-paying magazines such as Astounding Science Fiction, Pohl recalled in his memoirs that John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding, would occasionally pass on a good story by a prolific author because he felt readers did not want to see the same authors in every issue. As a result, Pohl was able to print L. Sprague de Camp's Genus Homo, in the March 1941 Super Science Stories, and Robert Heinlein's "Let There Be Light" and "Lost Legacy" in the May 1940 and November 1941 issues: these were stories which, in Pohl's opinion, "would have looked good anywhere".[35] Pohl also suggested that Campbell rejected some of Heinlein's stories because they contained mild references to sex. A couple of readers did complain, with one disgusted letter writer commenting "If you are going to continue to print such pseudosophisticated, pre-prep-school tripe as "Let There Be Light", you should change the name of the mag to Naughty Future Funnies".[35][notes 7]

The second run of Super Science Stories included some fiction that had first appeared in the Canadian reprint edition, which outlasted the US original. It printed eleven stories that had been acquired but not printed by the time Popular shut Super Science Stories and Astonishing down in early 1943. These included "The Black Sun Rises" by Henry Kuttner, "And Then – the Silence", by Ray Bradbury and "The Bounding Crown" by James Blish.[25][notes 8] From mid-1950 a reprint feature was established. This led to some reader complaints, with one correspondent pointing out that it was particularly galling to discover that Blish's "Sunken Universe", reprinted in the November 1950 issue, was a better story than the original material in the magazine.[1] The magazine also reprinted stories from Famous Fantastic Mysteries, which Popular had acquired from Munsey Publishing in 1941.[36]

Some of the original stories were well-received: for example, Ray Bradbury's "The Impossible", which appeared in the November 1949 issue, and was later included in Bradbury's book The Martian Chronicles, is described by sf historian Raymond Thompson as a "haunting ... comment on man's attempts to realize his conflicting hopes and dreams". Thompson also comments positively on Poul Anderson's early story "Terminal Quest", in Super Science Stories's final issue, dated August 1951; and on Arthur C. Clarke's "Exile of the Eons" in the March 1950 issue.[1] John D. MacDonald also contributed good material.[28]

The book reviews in Super Science Stories were of a higher standard than elsewhere in the field. Historian Paul Carter regards Astonishing and Super Science Stories as the place where "book reviewing for the first time began to merit the term 'literary criticism'", adding "it was in those magazines that the custom began of paying attention to science fiction on the stage and screen also".[5][37] The artwork was initially amateurish, and although it improved over the years, even the better artists such as Virgil Finlay and Lawrence Stevens continued to produce clichéd depictions of half-dressed women threatened by robots or aliens.[1] H. R. van Dongen, later a prolific cover artist for Astounding, made his first science fiction art sale to Super Science Stories for the cover of the September 1950 issue.[38]

Sf historian Mike Ashley regards Super Science Stories as marginally better than its companion magazine, Astonishing, adding "both are a testament to what a good editor can do with a poor budget".[7] According to sf critics Brian Stableford and Peter Nicholls, the magazine "had a greater importance to the history of sf than the quality of its stories would suggest; it was an important training ground".[2]

Bibliographic details

[edit]The first run of Super Science Stories was edited by Frederik Pohl from March 1940 through August 1941 (nine issues), and then by Alden H. Norton from November 1941 through May 1943 (seven issues). Ejler Jakobsson was the editor throughout the second run from January 1949 to August 1951. The publisher of both versions was Popular Publications, although the first was issued under its Fictioneers imprint. It was pulp-sized throughout both runs. At its launch, the magazine had 128 pages and was priced at 15 cents; the price increased to 20 cents when it grew to 144 pages in March 1941, and again to 25 cents for the May 1943 issue, which again had 128 pages. The second run was priced at 25 cents throughout and had 112 pages. The title was Super Science Stories for both runs except for three issues from March to August 1941, which were titled Super Science Novels Magazine. The volume numbering was completely regular, with seven volumes of four numbers and a final volume of three numbers. It was bimonthly for the first eight issues, from March 1940 to May 1941, and then went to a regular quarterly schedule.[1]

Canadian and British editions

[edit]| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | |||||||||

| 1943 | 1/4 | 1/5 | 1/6 | 1/7 | 1/8 | 1/9 | ||||||

| 1944 | 1/10 | 1/11 | 1/12 | 1/13 | 1/14 | 1/15 | ||||||

| 1945 | 1/16 | 1/17 | 1/18 | 1/19 | 1/20 | 1/21 | ||||||

| Issues of the Canadian edition of Super Science Stories, showing volume/issue number. Alden H. Norton was editor throughout. | ||||||||||||

In 1940, as part of the War Exchange Conservation Act, Canada banned the import of pulp magazines. Popular launched a Canadian edition of Astonishing Stories in January 1942, which lasted for three bimonthly issues and reprinted two issues of Astonishing and one issue of Super Science Stories. With the August 1942 issue the name was changed to Super Science Stories, and the numeration was begun again at volume 1 number 1; as a result the magazine is usually listed by bibliographers as a separate publication from the Canadian Astonishing, but in many respects it was a direct continuation. The price was 15 cents throughout; it lasted for 21 regular bimonthly issues in a single volume; the last issue was dated December 1945. It was published by Popular Publications' Toronto branch, and the editor was listed as Alden H. Norton.[36][39]

Each issue of the Canadian edition corresponded to one issue of either Astonishing or Super Science: for example, the first two Canadian issues drew their contents from the February 1942 Super Science Stories and the June 1942 Astonishing, respectively. This pattern continued for ten issues. The next issue, dated April 1944, contained several reprints from the US editions, but also included two original stories that had not appeared anywhere before—these had been acquired for the US magazine and remained in inventory. A total of eleven of these original stories appeared in the Canadian Super Science Stories. Later issues of the magazine also saw many reprints from Famous Fantastic Mysteries;[36] in tacit acknowledgment of the new source of material, the title was changed to Super Science and Fantastic Stories from the December 1944 issue.[25] The artwork was mostly taken from Popular's US magazines but some new art appeared, probably by Canadian artists. There was no other Canadian presence: the letters page, for example, contained letters from the US edition.[36]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 1950 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||

| 1951 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||||||

| 1952 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |||||||

| 1953 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |||||||||

| Issues of the two British editions of Super Science Stories, showing volume/issue number | ||||||||||||

In 1949, when the second run of the US Super Science Stories began, another Canadian edition appeared, but this was identical in content to the US version.[36] Two British reprint editions of the second run also appeared, starting in October 1949. The first was published by Thorpe & Porter; the issues, which were not dated or numbered, appeared in October 1949 and February and June 1950. The contents were drawn from the US issues dated January 1949, November 1949, and January 1950 respectively; each was 96 pages and was priced at 1/-. The second reprint edition was published by Pemberton's; these were 64 pages and again were undated and were priced at 1/-.[1]

The British issues are abridged versions of US issues from both the first and second series. The titles corresponded to the titles on the US magazine from which the stories were taken, so all were titled Super Science Stories except for the April 1953 issue, which was titled Super Science Novels Magazine.[1]

| Number | British release date | Corresponding US issue |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (unnumbered) | October 1949 | January 1949 |

| 2 (unnumbered) | February 1950 | November 1949 |

| 3 (unnumbered) | June 1950 | January 1950 |

| 1 | September 1950 | April 1949 |

| 2 | January 1951 | September 1950 |

| 3 | April 1951 | November 1950 |

| 4 | June 1951 | January 1951 |

| 5 | August 1951 | April 1951 |

| 6 | November 1951 | June 1951 |

| 7 | March 1952 | August 1951 |

| 8 | June 1952 | May 1943 |

| 9 | July 1952 | February 1943 |

| 10 | September 1952 | August 1942 |

| 11 | November 1952 | November 1942 |

| 12 | February 1953 | May 1942 |

| 13 | April 1953 | May 1941 |

| 14 | June 1953 | November 1941 |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pohl later realized that he got the job by an accident of timing; he applied just as the publisher needed new editors for a new line of magazines. Pohl commented that "they would have hired Mothra, or Og, Son of Fire, just about as readily right then, because they were very interested in expanding".[9]

- ^ By 1938, John W. Campbell at Astounding Stories was paying one cent per word, with a bonus for the readers' favorite story in the issue.[13]

- ^ For example, Isaac Asimov records that he was paid five-eighths of a cent per word for his story "Half-Breeds on Venus" in the June 1940 Astonishing Stories,[14] and Pohl paid himself three-quarters of a cent per word for "The King's Eye", which appeared in the February 1941 Astonishing under Pohl's "James McCreigh" pseudonyms.[15]

- ^ It is not clear from Pohl's memoirs exactly when this happened. According to his autobiographical essay "Ragged Claws" he was paid ten dollars a week for the first six months, which would imply his pay was increased in about April 1940. However, in his autobiography, The Way the Future Was, he makes it clear that the pay raise occurred after he was married in August 1940.[8][19]

- ^ Steeger was probably complaining about poor sales: Isaac Asimov recalls finding out on June 13, 1941, about Pohl's departure from Popular, and notes "his magazines were doing poorly, and he was being relieved of his editorial position".[21]

- ^ According to Pohl, there was ample paper at the mills in Canada, but because of the war there was no transportation available to bring it to the US.[27]

- ^ Pohl quotes a sample of the offensive material from "Let There Be Light": "'I suggest you follow the ancient Chinese advice to young women about to undergo criminal assault.' 'What's that?' 'Relax.'"[35]

- ^ "The Black Sun Rises" was first published in June 1944; "And Then – the Silence" first appeared in October 1944; and "The Bounding Crown" first appeared in December 1944. All three were first published in the US in the January 1949 Super Science Stories.[25][31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Raymond H. Thompson, "Super Science Stories", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines, pp. 631–635.

- ^ a b Brian Stableford & Peter Nicholls, "Super Science Stories", in Clute & Nicholls, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, p. 1187.

- ^ Malcolm Edwards & Peter Nicholls, "SF Magazines", in Clute & Nicholls, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, pp. 1066–1068.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 237–255.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Milton Wolf & Raymond H. Thompson, "Astonishing Stories", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines, pp. 117–122.

- ^ Pohl,The Way the Future Was, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 158–160.

- ^ a b c d Pohl, The Way the Future Was, p. 98.

- ^ Pohl, Early Pohl, p. 23.

- ^ "Astonishing Stories" in Tuck, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Vol. 3, p. 547.

- ^ Pohl, Early Pohl, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Pohl, The Way the Future Was, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Ashley, Time Machines, p. 107.

- ^ Asimov, In Memory Yet Green, p. 269.

- ^ Pohl, Early Pohl, p. 25.

- ^ Pohl, The Way the Future Was, p. 89.

- ^ Pohl, The Way the Future Was, p. 90.

- ^ Pohl, The Way the Future Was, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Frederik Pohl, "Ragged Claws", in Aldiss & Harrison, Hell's Cartographers, p. 155.

- ^ Pohl, The Way the Future Was, p. 102.

- ^ Asimov, Early Asimov: Vol. 2, p. 197.

- ^ Pohl, The Way the Future Was, p. 107.

- ^ Pohl, Early Pohl, p. 85.

- ^ Pohl, The Way the Future Was, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b c d e Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Pohl, Early Pohl, p. 131.

- ^ Pohl, Early Pohl, p. 129.

- ^ a b Ashley, Transformations, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Pohl, Early Pohl, p. 9.

- ^ Pohl, Early Pohl, p. 8.

- ^ a b c See the individual issues. For convenience, an online index is available at "Magazine:Super Science Stories – ISFDB". Al von Ruff. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Peter Nicholls, "James Blish", in Clute & Nicholls, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, pp. 135–137.

- ^ a b John Clute & Peter Nicholls, "Wilson Tucker", in Clute & Nicholls, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, p. 1244.

- ^ Asimov, Early Asimov: Vol. 2, pp. 235–237.

- ^ a b c Pohl, The Way the Future Was, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b c d e Raymond H. Thompson, "Super Science Stories (Canadian)", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines, pp. 635–637.

- ^ Carter, Creation of Tomorrow, p. 296.

- ^ Robert Weinberg, "Henry Richard van Dongen", in Weinberg, Biographical Dictionary of Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Grant Thiessen, "Astonishing Stories (Canadian)", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines, pp. 122–123.

Sources

[edit]- Aldiss, Brian W.; Harrison, Harry (1976). Hell's Cartographers. London: Futura. ISBN 0-86007-907-4.

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines:The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Ashley, Mike (2005). Transformations: The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-779-4.

- Asimov, Isaac (1973). The Early Asimov, or Eleven Years of Trying: Volume 2. London: Panther Books. ISBN 0-586-03936-8.

- Asimov, Isaac (1979). In Memory Yet Green. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-13679-X.

- Carter, Paul A. (1977). The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04211-6.

- Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- Pohl, Frederik (1979). The Way the Future Was. London: Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-02672-3.

- Pohl, Frederik (1980). The Early Pohl. London: Dobson. ISBN 0-234-72198-7.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1982). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3. Chicago: Advent:Publishers. ISBN 0-911682-26-0.

- Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (1985). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Weinberg, Robert (1985). A Biographical Dictionary of Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

External links

[edit]- Super Science Stories, images of all covers of Super Science Stories