STS-135

Atlantis lands at the Kennedy Space Center on July 21, 2011, bringing the Shuttle program to an end. | |

| Names | Space Transportation System-135 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | ISS logistics |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2011-031A |

| SATCAT no. | 37736 |

| Mission duration | 12 days, 18 hours, 28 minutes, 50 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 8,505,161 km (5,284,862 mi) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Atlantis |

| Launch mass |

|

| Landing mass | 102,682 kg (226,375 lb) |

| Payload mass | 12,890 kg (28,418 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 4 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | July 8, 2011 15:29:04 UTC,[1][2] 11:29:04 am EDT |

| Launch site | Kennedy, LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | July 21, 2011, 09:57:54 UTC, 5:57:54 am EDT |

| Landing site | Kennedy, SLF Runway 15 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Inclination | 51.6° |

| Period | 91 minutes |

| Docking with ISS | |

| Docking date | July 10, 2011 15:07 UTC |

| Undocking date | July 19, 2011 06:28 UTC |

| Time docked | 8 days, 15 hours and 21 minutes |

From left: Walheim, Hurley, Ferguson and Magnus | |

STS-135 (ISS assembly flight ULF7)[3] was the 135th and final mission of the American Space Shuttle program.[4][5] It used the orbiter Atlantis and hardware originally processed for the STS-335 contingency mission, which was not flown. STS-135 launched on July 8, 2011, and landed on July 21, 2011, following a one-day mission extension. The four-person crew was the smallest of any shuttle mission since STS-6 in April 1983. The mission's primary cargo was the Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) Raffaello and a Lightweight Multi-Purpose Carrier (LMC), which were delivered to the International Space Station (ISS). The flight of Raffaello marked the only time that Atlantis carried an MPLM.[6]

Although the mission was authorized, it initially had no appropriation in the NASA budget, raising questions about whether the mission would fly. On January 20, 2011, program managers changed STS-335 to STS-135 on the flight manifest. This allowed for training and other mission specific preparations.[7] On February 13, 2011, program managers told their workforce that STS-135 would fly regardless of the funding situation via a continuing resolution.[8] Until this point, there had been no official references to the STS-135 mission in NASA documentation for the general public.[9][10][11][12]

During an address at the Marshall Space Flight Center on November 16, 2010, NASA administrator Charles Bolden said that the agency needed to fly STS-135 to the station in 2011 due to possible delays in the development of commercial rockets and spacecraft designed to transport cargo to the ISS. "We are hoping to fly a third shuttle mission (in addition to STS-133 and STS-134) in June 2011, what everybody calls the launch-on-need mission... and that's really needed to [buy down] the risk for the development time for commercial cargo", Bolden said.[13]

The mission was included in NASA's 2011 authorization,[14] which was signed into law on October 11, 2010, but funding remained dependent on a subsequent appropriations bill. United Space Alliance signed a contract extension for the mission, along with STS-134; the contract contained six one-month options with NASA in order to support continuing operations.[15]

The federal budget approved in April 2011 called for US$5.5 billion for NASA's space operations division, including the shuttle and space station programs. According to NASA, the budget running through September 30, 2011, ended all concerns about funding the STS-135 mission.[16]

Crew

[edit]

NASA announced the STS-335/135 crew on September 14, 2010.[17] Only four astronauts were assigned to this mission, versus the normal six or seven, because there were no other shuttles available for a rescue following the retirement of Discovery and Endeavour. If the shuttle was seriously damaged in orbit, the crew would have moved into the International Space Station and returned in Russian Soyuz capsules, one at a time, over the course of a year. All STS-135 crew members were custom-fitted for a Russian Sokol space suit and molded Soyuz seat liner for this possibility.[18] The reduced crew size also allowed the mission to maximize the payload carried to the ISS.[19] It was the only time that a Shuttle crew of four flew to the ISS. The last shuttle mission to fly with just four crew members occurred 28 years earlier: STS-6 on April 4, 1983, aboard Space Shuttle Challenger.

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Christopher Ferguson Third and last spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Douglas Hurley Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Sandra Magnus Third and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 Flight Engineer |

Rex Walheim Third and last spaceflight | |

Crew seat assignments

[edit]| Seat[20] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the flight deck. Seats 5–7 are on the mid-deck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ferguson | ||

| 2 | Hurley | ||

| 3 | Magnus | ||

| 4 | Walheim | ||

| 5 | Unused | ||

| 6 | Unused | ||

| 7 | Unused | ||

Funding

[edit]With support from both the House of Representatives and the Senate, the fate of STS-135 ultimately depended on whether lawmakers could agree to fund converting the mission from launch-on-need to an actual flight.[4] On July 15, 2010, a Senate committee passed the 2010 NASA reauthorization bill, authored by Senator Bill Nelson (D-FL), to direct NASA to fly an extra Space Shuttle mission (STS-135) pending a review of safety concerns.[21] The bill still needed the approval of the full Senate. A draft NASA reauthorization bill considered by the House Science & Technology Committee did not provide for an extra shuttle mission.[22] On July 22, 2010, during a meeting of the House Science Committee, U.S. Rep. Suzanne Kosmas (D-FL) successfully amended the House version of the bill to add an additional shuttle mission to the manifest.[23]

On August 5, 2010, the Senate passed its version of the NASA reauthorization bill, just before lawmakers left for the traditional August recess.[24][25] On August 20, 2010, NASA managers approved STS-135 mission planning targeting a June 28, 2011, launch.[4] On September 29, 2010, the House of Representatives approved the Senate-passed bill on a 304–118 vote.[26] The bill, approved by the U.S. Congress, went to President Barack Obama for his signature.[27]

On October 11, 2010, Obama signed the legislation into law, allowing NASA to move forward with STS-135,[5][28] though without specific funding. Generally, the average cost of a shuttle mission was about $450 million.[29]

On January 20, 2011, STS-135's designation was officially changed from STS-335.[7] On February 14, 2011, NASA managers announced that STS-135 would fly regardless of the funding situation in Congress.[30]

Mission parameters

[edit]- Mass:[2]

- Total liftoff weight: 4,521,143 pounds (2,050,756 kg)

- Orbiter liftoff weight: 266,090 pounds (120,700 kg)

- Orbiter landing weight: 226,375 pounds (102,682 kg)

- Payload weight: 28,418 pounds (12,890 kg)

- Perigee: TBD

- Apogee: TBD

- Inclination: 51.6°

- Period: 91 minutes

Payload

[edit]STS-135 delivered supplies and equipment to provision the space station through 2012, following the end of NASA's Space Shuttle program. Since the ISS program was extended to 2024[31] (now 2030), the station is resupplied by the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services program which took over resupply missions from the Shuttle. A shuttle extension beyond STS-135 wasn't seriously considered, and an ISS extension was never intended to be a guaranteed shuttle program extension,[32] and the Shuttle program officially ended after STS-135.[33]

-

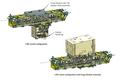

STS-135: MPLM rack complement.

-

STS-135: LMC RRM up and ETCS/PM down payload.

-

Graphic representation of the RRM on ELC-4 with the SPDM on the right.

-

Pico-Sat Solar Cell (PSSC-2) experimental picosatellite breakdown.

Multi-Purpose Logistics Module

[edit]The Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) Raffaello made up the majority of the payload. This was Raffaello's fourth trip to the International Space Station since 2001 and the 12th use of an MPLM. Unlike previous MPLM missions that delivered large compartments and devices to outfit the space station laboratories, STS-135 delivered only bags and supply containers. The MPLM was filled with 16 resupply racks, which is the maximum that it could handle. Eight Resupply Stowage Platforms (RSPs), two Integrated Stowage Platforms (ISPs), six Resupply Stowage Racks (RSRs) and one Zero-G Stowage Rack (ZSR), which sits above another rack during transport.[34]

On flight day 4, Raffaello was lifted out of Atlantis's payload bay using the station's Canadarm2. It was berthed to nadir port of the Harmony node. After completing the cargo transfers to the ISS, Raffaello was loaded with almost 5,700 pounds (2,600 kg) of unneeded equipment and station waste to be brought back to Earth. On flight day 11, the MPLM was detached from Harmony and was secured in the cargo bay of the shuttle.

Lightweight Multi-Purpose Carrier

[edit]The Lightweight Multi-Purpose Carrier (LMC) was also carried on STS-135. The External Thermal Cooling System (ETCS) Pump Module (PM) stored on ESP-2, which failed and was replaced on orbit in August 2010, rode home on the LMC so that a failure analysis can be performed on the ground. The Robotic Refueling Mission rode up to the station on the underside of the LMC and was placed onto the ELC-4.

Robotic Refueling Mission

[edit]Atlantis carried the Robotic Refueling Mission (RRM) developed by the Satellite Servicing Capabilities project at the Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC).[35] It planned to demonstrate the technology and tools to refuel satellites in orbit by robotic means.[36] After the proof of concept, the long-term goal of NASA is to transfer the technology to the commercial sector.[36]

RRM included four tools, each with electronics and two cameras and lights. Additionally, it had pumps and controllers and electrical systems such as electrical valves and sensors.[37]

The RRM payload was transported to the Kennedy Space Center in early March 2011, where the GSFC team performed the final preparations for space flight.[citation needed] Once up on the International Space Station, RRM will be installed into the ELC-4.[clarification needed] The Dextre robot was planned to be used in 2012 and 2013 during the refueling demonstration experiments.[38]

Picosatellite Solar Cell Testbed 2

[edit]Space Shuttle Atlantis carried a miniaturised satellite known as PSSC-2, or Picosatellite Solar Cell Testbed 2 into orbit. PSSC-2 was successfully deployed from the shuttle's cargo bay on flight day 13, becoming the 180th and last Space Shuttle payload to be placed into orbit.

TriDAR

[edit]The mission was the third flight of the TriDAR sensor package designated DTO-701A (Detailed Test Objective), a 3D dual-sensing laser camera, intended for use as an autonomous rendezvous and docking sensor.[39] It was developed by Neptec Design Group and funded by NASA and the Canadian Space Agency. TriDAR had previously flown on STS-128 and STS-131, aboard Space Shuttle Discovery. TriDAR provides guidance information that can be used for rendezvous and docking operations in orbit, planetary landings and vehicle inspection/navigation of robotic rovers. It does not rely on any reference markers, such as reflectors, positioned on the target spacecraft, instead using a laser-based 3D sensor and a thermal imager. Geometric information contained in successive 3D images is matched against the known shape of the target object to calculate its position and orientation in real-time.

The sensor was emplaced on the exterior airlock truss next to a Trajectory Control System (TCS) sensor. The TriDAR hardware was installed in Atlantis's payload bay on April 6, 2011. On STS-135, TriDAR was used to demonstrate technology for autonomous rendezvous and docking in orbit.

Down-mass payload

[edit]STS-135 returned to Earth carrying several items of downmass payload. The failed ammonia Pump Module that was replaced in August 2010 was returned inside Atlantis's payload bay, on the upper side of the LMC. Also, a problematic Common Cabin Air Assembly (CCAA) Heat Exchanger (HX) was expected to be returned inside the MPLM. The shuttle also brought back material, including experiments, in its middeck lockers. Since STS-135 only had four crew members, astronauts did not occupy the middeck. Resultingly, compared to previous shuttle missions to the Space Station, additional storage space was available.

-

Raffaello in the Space Station Processing Facility.

-

A view of the RRM on the underside of the LMC in the SSPF with technicians for scale

-

The failed Pump Module (PM) on the right in this image of the ESP-2 platform

Other supplies

[edit]An iPhone was used by astronauts to log experiments, and was left on the ISS for future use.[40] Two Nexus S smartphones were also installed inside Synchronized Position Hold, Engage, Reorient, Experimental Satellites (SPHERES) to allow the crew to pilot them aboard the ISS.[41]

Shuttle processing

[edit]

External Tank 138 (ET-138) was produced at the Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans and arrived at the Kennedy Space Center on the Pegasus barge.[42] After offloading, the tank was transported into a checkout cell inside the VAB on July 14, 2010.

NASA initially planned for STS-134 (Endeavour) to fly with the newer ET-138 and for the LON STS-335 (Atlantis) mission to utilize the refurbished ET-122 only in the event that a rescue of Endeavour's crew were required. During Hurricane Katrina, ET-122 was damaged at the Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans and while the tank was certified as completely flight-worthy after its repairs were completed, NASA management ruled that ET-122 posed a slightly higher risk of losing foam from the repaired areas and therefore assigned it to the STS-335 mission that would likely never fly. However, once it was decided to fly Atlantis on a full STS-135 mission, the tank assignments were swapped so that in the event STS-134 (Endeavour) were to suffer damage from ET-122, Atlantis with the newer and less risky ET-138 would be poised to rescue Endeavour's crew.[43]

In early December 2010, ground technicians installed the main engines on Atlantis. The Shuttle received the center engine on December 7, 2010, followed by the lower-right engine and the lower-left on December 8 and 9, 2010 respectively inside Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF-1). The event marked the last set of main engines to be installed on a Space Shuttle.[44]

Stacking operations of the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) for the mission commenced in the evening hours of March 29, 2011.[45] Technicians inside the VAB, lifted the left-aft segment from the handling crate and carefully maneuvered into High Bay No. 1 and finally onto the mobile launch platform. The booster stacking was completed in mid April. The completed boosters had a mixture of refurbished and unflown elements (11 sections on each booster). For example, the forward dome for the right-hand booster is new, while the upper cylinder on the left booster flew with STS-1 – the historic maiden flight of Space Shuttle Columbia.[46] (For detailed information on the STS-135 boosters, see[47])

After completing the assembly process, the ET-138 was mated to the SRBs on April 25.[48]

Visit by President Obama's family

[edit]President Barack Obama, his wife Michelle Obama, and their daughters, Malia and Sasha, viewed Atlantis at the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF-1) on their visit to the Kennedy Space Center on April 29, 2011.[49] The president's family missed the launch of Endeavour on the STS-134 mission, as the first launch attempt was scrubbed due to problems with two heaters on one of Endeavour's auxiliary power units (APUs).

During their tour of the Orbiter Processing Facility, the president's family was accompanied by United Space Alliance tile technician Terry White and astronaut Janet Kavandi. Standing under the wings of Space Shuttle Atlantis, White gave the president and his family an informal tutorial.[50]

Rollover

[edit]

On the early morning of May 17, 2011, Space Shuttle Atlantis departed OPF-1 and headed to the VAB for mating operations with ET-138.[51] The short trip took longer than normal and allowed the shuttle workers to pose for a photo opportunity with the shuttle. The four STS-135 astronauts were also present to greet the workers and representatives of the media.[52][53] Atlantis remained on the Orbiter Transport System overnight, as opposed to heading over to High Bay 1 on the same day.

Inside the VAB transfer aisle, lifting operations to rotate Atlantis vertically commenced on May 18, 2011. The crane that hoisted the shuttle placed it into the adjacent high bay. Atlantis was next lowered to meet up with the external tank and the two solid rocket boosters. The mating operations were completed on May 19, 2011. On the same day, NASA officially announced July 8, 2011, as the intended launch date of the STS-135 mission.

Rollout

[edit]Atlantis was rolled out to Launch Pad 39A on June 1.[54] The first motion of Atlantis out of the Vehicle Assembly Building began at 20:42 EDT on May 31, 2011. Due to a minor hydraulic leak on a corner valve for the jacking and elevation system on the crawler-transporter, the move was delayed by 40 minutes.[55] After the 3.4-mile (5.5 km) journey, the shuttle was secured on the launch pad at 03:29 EDT on June 1, 2011.[56][57][58]

Large crowds, including the families of NASA's workforce, were present during the rollout. The STS-135 crew was also at the Kennedy Space Center to witness the last-ever rollout of a Space Shuttle. The crew participated in an informal Question & Answer session with news media, which was aired live on NASA TV. While Atlantis was rolled out to the launch pad, Endeavour was landing a few miles away at the Shuttle Landing Facility, touching down on Kennedy Space Center's Runway 15 at 02:34 EDT after completing its final mission, STS-134.

-

President Obama and his family view Atlantis at OPF-1.

-

Atlantis is lowered toward the External Tank and the Solid Rocket Boosters.

-

The shuttle's main cargo, the Raffaello MPLM and LMC, inside the payload bay.

-

Atlantis at the Launch Pad after completing its rollout.

External tank fueling test

[edit]Atlantis's external tank for the STS-135 mission was put through a tanking test on June 15, 2011, to check the health of the tank's stringers.[59] It was slightly delayed due to a lightning storm which passed over the Kennedy Space Center. During the test, technicians detected a hydrogen fuel valve leak in Atlantis's main engine No. 3, as it recorded temperatures below normal levels.[60] The leaking hydrogen valve was replaced on June 21.[61]

On June 18, engineers also commenced X-ray inspections to verify the performance of the radius block doublers that were installed over the top of the stringers. The stringers form the backbone of ET-138's central "intertank" compartment that separates the upper liquid oxygen tank from the larger liquid hydrogen tank below. The installation of the doublers on ET-138 was ordered after engineers found stringer cracks in the tank used for Discovery's STS-133 mission. Technicians finished all X-ray scans of the stringers on June 24, well ahead of schedule. After analyzing the results, they found no issues.[62]

Payload canister

[edit]

The STS-135 payload canister's move to Launch Pad 39A began in the night of June 16.[63] The canister's lifting up of the pad structure to place it into the cleanroom happened on the next day.[64] Technicians at the launch pad closed the Rotating Service Structure (RSS) back around Atlantis to gain access to the orbiter's payload bay. The payload bay doors were opened on the night of June 18 and the cargo was installed into the shuttle's payload bay on June 20.

Terminal countdown demonstration test

[edit]The STS-135 crew then traveled to Kennedy Space Center, arriving in T-38 training jets just after 17:30 EDT on June 20 to take part in the countdown dress rehearsal and emergency training drills.[65] After the arrival, the four astronauts spoke to reporters at the runway and acknowledged the historic nature of the final shuttle mission. "We're incredibly proud to represent the final flight," noted the commander, Chris Ferguson.[66] During the training, the crew spent time learning pad 39A evacuation procedures and test-drove an armored tank available for the astronauts to escape the area. They also boarded Atlantis for a full countdown simulation on June 23.

Launch attempts

[edit]| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 Jul 2011, 11:29:04 am | Success | — | initially 30%, later 60% | Initial weather reports indicated concerns for clouds, thunderstorms and lightning in the area. Countdown was held at 31 seconds to verify gaseous oxygen vent arm had fully retracted. Launch time 11:29:04[67][68] |

Mission timeline

[edit]July 8 (Flight Day 1 – Launch)

[edit]

The launch day was threatened by unfavorable weather leaving only a 30% chance of a launch occurring;[69] this changed an hour before launch to 60% chance of launch.[70] Launch director Mike Leinbach conducted the final series of GO/NO GO polls to verify the launch readiness. Shuttle Launch Integration Manager Michael P. Moses also issued a waiver for return to launch site (RTLS) weather. Later at the post-launch news conference, Moses explained that his decision was based on the fact although a few showers that were popping up within the 20-nautical-mile (37 km) radius from the Shuttle Landing Facility at RTLS landing were a launch constraint, the showers would have been cleared by the time of a RTLS landing (if it did) 35 minutes later.

At the end of the poll Leinbach told the crew "Good luck to you and your crew on the final flight of this true American icon. Good luck, godspeed and have a little fun up there" to which commander Chris Ferguson replied "Thanks to you and your team Mike, until the very end you all made it look easy. The Shuttle will always be reflection of what a great nation can do when it dares to be bold and commit to follow through. We're completing a chapter of a journey that will never end. The crew of Atlantis is ready to launch".

At T−31 seconds, just before Atlantis's computers were supposed to take control of the flight, the launch countdown clock stopped. This was because of a lack of an indication that the Gaseous Oxygen Vent Arm had retracted and properly latched, a problem that had never occurred during previous launches in the program's history. Soon the launch team was able to verify the Vent Arm's position with the help of a closed circuit camera, and the countdown clock resumed after approximately 2 minutes, 18 seconds.

The final flight of Space Shuttle Atlantis launched from the Kennedy Space Center on July 8 at 11:29:03.9 EDT with launch commentator George Diller saying, "All three engines up and burning, two, one, zero and liftoff! The final liftoff of Atlantis – on the shoulders of the space shuttle, America will continue the dream".[71] The launch was cheered by a crowd of nearly one million inside the Kennedy Space Center and in the surrounding area.[72][73] Powered flight conformed to the standard timeline, with the two boosters separating from the ET after two minutes and five seconds, and the main engine cutoff (MECO) occurring at 15:37:28 GMT at a Mission Elapsed Time (MET) of 8 minutes and 24 seconds. The external tank, ET-138, separated from the shuttle at 15:37:49 GMT. A modification made in the ET-138 camera allowed it to beam back video of the tank's disintegration in the atmosphere.[74] A further boost from the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines (the OMS-1 burn) was not required due to the nominal MECO, and Atlantis settled into an initial 225 x 58 km roughly 51.6 degree orbit.[75] The crew performed several course correction actions on Flight Day 1. These included the 64 seconds OMS-2 burn which pushed Atlantis into a 230 x 158 km orbit and the NC-1 engine firing for 94 seconds to adjust the shuttle's orbital path to match with the Space Station. The NC-1 firing altered the shuttle's velocity by about 144.7 ft/s (44.1 m/s).

NASA held a post-launch news conference at 12:10 CDT with Bill Gerstenmaier, Robert Cabana (director of NASA's John F. Kennedy Space Center), Mike Moses and Mike Leinbach.

After opening the shuttle's payload bay doors at 17:03:20 GMT, the crew began configuring Atlantis for on-orbit operations. The Ku-band antenna was deployed and the self-test was completed with satisfactory results.[76] CAPCOM astronaut Barry Wilmore radioed the crew from mission control in Houston, reporting that a preliminary analysis found no signs of any significant debris or impact damage during the ascent.[77] Commander Ferguson and Pilot Hurley also powered up the Shuttle's Robotic Arm and checked its functions ahead of next day's planned thermal protection survey.

-

Crew at the traditional pre-launch breakfast.

-

Crew alongside the Astrovan before heading to the launch pad.

-

The crew after arriving at the launch pad.

-

Michael Leinbach monitors the launch countdown from Firing Room Four of the Launch Control Center at the KSC.

-

Launch of Atlantis viewed through the window of a Shuttle Training Aircraft.

-

ET-138 floats away from the shuttle.

July 9 (Flight Day 2 – TPS survey)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

A crowd at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center greeted the crew with a unique "good morning" call. "Good morning Atlantis, the Marshall Space Flight Center hopes you enjoyed your ride to orbit."[78] We wish you a successful mission and a safe return home," the workers said in a recorded video message.[79]

The main objective of the day was to inspect Atlantis's thermal protection system, using the shuttle's robotic arm and the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) to look for any signs of launch damage.[80] To do so, Commander Ferguson, Pilot Hurley and Mission Specialist Magnus used the shuttle's robotic arm and the OBSS to get a close up look at reinforced carbon–carbon wing leading edges and the nose cap of the shuttle. The robotic arm grappled the OBSS at 6:58 a.m. EDT. After raising out the arm-boom assembly, the crew activated the camera and laser sensor package on the boom to first scan the starboard wing. The nose cap was surveyed next followed by the port wing. The gathered visual and electronic data were downlinked during numerous Ku band communication opportunities to the ground. With imagery on their hand, experts began to review the data. The heat shield survey started around 11:00 UTC, was wrapped about five hours later. In his NASA TV commentary, NASA Public Affairs Officer, Rob Navias, said that most of the time, the crew worked ahead of schedule opting to take meals while working. The crew received high praise for their efficient work from the Mission Control Houston including CAPCOM astronaut Stephen Robinson who communicated with them during the survey.

While the TPS survey was under way, Mission Specialist Walheim spent much of his afternoon on the shuttle's middeck. He worked to prepare items carried into orbit there for transfer to the space station.[81] Later in the day, Walheim worked with Hurley to check out the rendezvous tools that would be used during Atlantis's docking with the ISS on Flight Day 3. Meanwhile, Ferguson and Magnus installed the center-line camera in the window of the shuttle's hatch for a view that would help them align Atlantis with the space station.

The NC2 and NC3 course correction burns were also performed during Flight Day 2 to change the flight path of Atlantis en route to the ISS. The NC3 maneuver lasted seven seconds and changed the shuttle's velocity by about 1.5 feet per second (0.46 m/s). Aboard the ISS, the Expedition 28 crew completed the pressurization of Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA-2), located at the forward docking port of the Harmony module, ahead of the shuttle's docking. Crew members Fossum, Volkov and Furukawa also held a meeting with the ground imagery experts to discuss the planned photography shoot during Atlantis's rendezvous pitch maneuver (RPM).

During the mission status briefing from the Johnson Space Flight Center (JSC), shuttle flight director Kwatsi Alibaruho said that Atlantis was off to one of the smoothest starts of any mission in the 30-year history of NASA's shuttle program. He told reporters, "I think this is certainly one of the better starts that we have seen".[citation needed]

July 10 (Flight Day 3 – Docking)

[edit]

The STS-135 crew began their day at 07:29 UTC and prepared to dock with the ISS.[82] The crew encountered a minor problem when Atlantis's General Purpose Computer (GPC3) failed.[83] However, this held no impacts for the rendezvous and docking operations as two GPCs proved sufficient.

Commander Chris Ferguson and pilot Douglas Hurley performed a series of rendezvous burns (NH, NC4, NCC, MC1-4 and TI) to boost the orbit of Atlantis to match with that of the ISS. At 11:40 UTC, with about 9 miles (14 km) separating the shuttle and the ISS, Ferguson performed the final 12-second terminal initiation (TI) burn, firing the left OMS engine of Atlantis at 12:29 UTC. It placed the shuttle 1,000 feet (300 m) below the Space Station at 13:51 UTC.[84] By 13:26 UTC, with Ferguson flying Atlantis from the aft flight deck, the shuttle positioned 600 feet (180 m) beneath the ISS and began the 360-degree flip rendezvous pitch maneuver (RPM). As the shuttle's underside rotated into view, three of the Expedition 28 ISS crew members – Sergei Volkov, Mike Fossum and Satoshi Furukawa using cameras with 1000 mm, 800 mm and 400 mm lenses, respectively, photographed Atlantis's under belly for 90 seconds, as part of post-launch inspections of the thermal protection system. The photos were sent to mission control in Houston to be evaluated by experts on the ground to look for any damage.

Atlantis docked with the ISS Pressurized Mating Adapter-2 at 15:07 UTC as the two orbited 220 miles (350 km) over the South Pacific Ocean east of New Zealand.[85] This was Atlantis's 19th docking to a Space Station. "Houston, station, Atlantis, capture confirmed and we see free drift," radioed Hurley, confirming the successful docking.[86] In reply, "Atlantis arriving," said Ron Garan after the ceremonial ringing of the station's bell. "Welcome to the International Space Station for the last time".[87] A series of leak checks were done on both sides of the hatches, before they were opened at 16:47 UTC. Shortly afterwards, the shuttle crew floated into the station's Harmony module at 16:55 UTC. After a brief welcoming ceremony by the station crew, Atlantis's astronauts received the standard station safety briefing.

The crew then got to work with Ferguson and Hurley using the shuttle arm to take its OBSS from the station's Canadarm2 operated by Garan and Furukawa. The station arm had plucked the OBSS from its stowage position on the shuttle cargo bay sill. The handoff was to prepare to use the boom for any shuttle heat shield late inspections if required. Magnus worked with TV setup and Walheim transferred spacewalk gear.

During Flight Day 3, flight controllers began monitoring reports from the Department of Defense's U.S. Strategic Command that an orbital debris piece of the Russian satellite COSMOS 375 may come near the station and shuttle complex about noon the next day. The team updated tracking information following the docking and determined that no course correction maneuver was necessary.[88]

-

Atlantis over the Bahamas.

-

Closeup view of the ISS as photographed by a STS-135 crewmember.

-

After the hatch opening, the ISS and STS-135 crews are united.

July 11 (Flight Day 4 – MPLM installation)

[edit]

The main objective of Flight Day 4 was to install the Raffaello MPLM on the nadir port of the station's Harmony module.[89] The crew started their day in space at 7:02. The song Tubthumping by Chumbawamba was played to wake the astronauts up.[90] Mission Specialist Sandra Magnus, along with Pilot Doug Hurley, used the Canadarm2, beginning at 9:09 UTC, to remove the Raffaello module from the payload bay of Atlantis. The two installed the MPLM on the Harmony node at 10:46 UTC.[91] After leak checks, hatches between Raffaello and the ISS were opened before noon.

Because Atlantis launched on time with a full load of onboard consumables for its electricity-generating fuel cells, and due to power saving operations employed during the first three days, on Flight Day 4, NASA's managers approved a one-day mission extension. According to NASA, the mission was extended primarily to allow the crew to spend more time on cargo transfers. CAPCOM Megan McArthur also notified commander Chris Ferguson that the Mission Management Team decided not to do a Focused Inspection of the Atlantis's heat shield. The Damage Assessment Team had only found one tile ding along with four areas of minor damage to insulating blankets, said chairman Leroy Cain during the day's Mission Management Briefing aired on NASA TV.

Shortly before the end of their workday, STS-135 crew members and Expedition 28 crew members Ron Garan, Mike Fossum and Satoshi Furuakawa met for about an hour to review procedures for the next day's spacewalk.[92]

-

A Virtual view (recreation) of an STS-134 image edited to show how the two MPLMs would look during STS-135.

-

Rex Walheim on the flight deck of Atlantis

-

Hurley moves around supplies and equipment in Leonardo PMM.

July 12 (Flight Day 5 – Station spacewalk)

[edit]

Flight day 5 saw Expedition 28 Flight Engineers Mike Fossum and Ron Garan perform a spacewalk.[93] Because of a short training flow and a requirement to launch the shuttle with a reduced crew of four, NASA opted not to utilize two spacewalkers from the STS-135 crew. The main tasks for the spacewalk included retrieving a failed pump module from an external stowage platform of the ISS for return to Earth inside the shuttle's cargo bay, installing two experiments and repairing a new base for the station's robotic arm. The spacewalk began at 13:22 UTC (NASA Rule). For identification, Fossum's EMU spacesuit had red stripes around the legs, while Garan's had no markings. The spacewalkers used Canadarm2 to retrieve the pump module which failed in 2010. Operated by STS-135 Pilot Hurley and Mission Specialist Magnus in the station's cupola, Garan rode Canadarm2 to the pump module's stowage platform where he and Fossum removed it. Still on the arm, Garan took the pump module inside Atlantis's payload bay. There Fossum bolted it into place on the LMC. The astronauts next removed the Robotics Refueling Mission (RRM) experiment from the payload bay. Fossum, now on the arm, carried the experiment to a platform on Dextre for temporary storage, while Garan cleaned up tools and equipment in the payload bay of Atlantis. Recognizing the historical significance, Mission Specialist Rex Walheim, who served as the intra-vehicular officer to coordinate the spacewalk from Atlantis's flight deck, radioed: "Take a look around, Ronny. You're the last EVA person in the payload bay of a shuttle."[94]

Upon completion of the installation, Fossum moved to the front of the Zarya module and freed a wire stuck in one latch door at a data grapple fixture. The fixture had been installed during STS-134, the previous shuttle mission. The grapple fixture serves as a base for Canadarm2, considerably extending its range of operation on the Russian segment of the ISS. Garan also deployed a materials experiment (MISSE-8) that focuses on optical reflector materials, also installed during STS-134, on the Express Logistics Carrier (ELC-2) FRAM-3 site on the station's starboard truss. Back together again, Fossum and Garan moved on to the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA-3) on the Tranquility node. They installed an insulating cover on the end of the adapter, an area exposed to considerable sunshine.

The two astronauts completed the six-hour, 31-minute spacewalk at 19:53 UTC.[95] It was the 160th spacewalk in support of ISS assembly and maintenance and 249th spacewalk by U.S. astronauts.[96] Inside the shuttle-station complex, transfer of material from the Raffaello MPLM began.

A urine processor in a U.S. toilet located in the Tranquility module was turned off since on Flight Day 4, as the astronauts reported a strong odor from the equipment. The decision was made since during the spacewalk, Hurley and Magnus used a robotics work station in the cupola.

-

Fossum rides on Canadarm2 as he transfers the RRM to the Dextre robot. Note MPLM Raffaello in the background.

-

Sandy Magnus works inside the Cupola

-

A composite of photos taken during the station spacewalk of the overall ISS from ELC-2, note MISSE-8 PEC on the right

-

MISSE-8 ORMatE-III exposure plate' placed on ELC-2 during the spacewalk

July 13 (Flight Day 6 – Cargo transfers)

[edit]

The Atlantis crew received a special wakeup message from Sir Elton John to start flight day 6.[97] The message followed the day's wakeup song which was played at 6:29 UTC.[98] Atlantis's crew focused on unpacking supplies from the Raffaello MPLM. The crew started the day 26 percent through the combined 15,069 pounds of cargo to transfer in or out of Raffaello. The MPLM was launched with 9,403 pounds of cargo and was expected to return 5,666 pounds when Atlantis landed. The supplies and equipment that Atlantis astronauts delivered to the orbiting outpost was expected to keep the station well supplied through 2012.[99]

The crew had some help from the station crew of Andrey Borisenko, Sergei Volkov and Satoshi Furukawa in the transfer operations. Crew members also opened the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA-3), attached to the Tranquility node, and stored some of the material from Raffaello there. Station lead flight director Chris Edelen said at an afternoon briefing that about 50% of the cargo had been moved from Raffaello and the shuttle's middeck to the space station.[100]

All four shuttle crew members took some time out of their work at 16:54 UTC to talk with reporters from WBNG-TV and WICZ-TV in Binghamton, New York, near Pilot Doug Hurley's home town of Apalachin and KGO-TV of San Francisco.

During Flight Day 6, Space Shuttle Discovery was moved from the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF-2) to the nearby Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to enter storage. This move was planned in order to house Atlantis in OPF-2 after landing.[101]

July 14 (Flight Day 7 – Cargo transfers/Off-duty)

[edit]

Flight Day 7 saw crew unpacking more cargo from the Raffaello MPLM.[102]

The crew also took some time off to participate in several special events. At 10:59 UTC, Commander Ferguson and Mission Specialist Magnus spoke with reporters from Fox News Radio and KTVI-TV and KSDK-TV in St. Louis. Then, at about 13:20 UTC, the entire crew was interviewed by WBBM-TV in Chicago, KTVU-TV in Oakland, California, and WTXF-TV in Philadelphia. Afterward the shuttle crew had most of the afternoon off.[103] For dinner, both the Atlantis and station crews enjoyed a special "All-American Meal" of barbecue brisket or grilled chicken and baked beans, southwestern corn and apple pie.[104] NASA invited the public to share in it, virtually.

NASA on flight day 7 released the video captured by cameras mounted on each of Atlantis's solid rocket boosters showing the launch of the shuttle.

The shuttle astronauts went to sleep as planned but were awakened by the sound of a master alarm on board Atlantis at 22:07 GMT. The tone signaled a failure with one of Atlantis's five IBM AP-101 General Purpose Computers (GPCs) No. 4.[105] The alarm prompted Commander Ferguson to head to Atlantis and evaluate the issue. GPC-4 was running system management software at the time of failure. Ferguson with the help of Ground Control later transferred the failed GPC's programs onto GPC-2. The transfer took about 45 minutes, bypassing an expected period of loss of signal by utilizing communications at White Sands, New Mexico. After activating GPC-2 and with Atlantis in good shape, Ferguson and other crew members went back to sleep. "You all have done an absolutely fabulous job. We have polled the room, everyone is ready for you to go back to sleep," radioed CAPCOM Shannon Lucid from Mission Control.[106]

As a result of the extra time spent on fixing the GPC-4 issue, Mission Control extended the crew sleep period by 30 minutes. Although no root cause was immediately identified, ground controllers immediately ruled out any connection between GPC-4 malfunction and the problem suffered by GPC-3 ahead of docking.[107]

July 15 (Flight Day 8 – Cargo transfers)

[edit]

The crew awakened at 4:59 UTC to a special message and a song from Sir Paul McCartney.[108] The wake up call was 30 minutes later than Atlantis's crew had been scheduled in order to give them time to make up sleep they lost over the course of the night due to the failure of GPC-4. Early on the day, Atlantis commander Ferguson and pilot Hurley re-loaded software and successfully restarted the GPC-4.[109] Flight controllers in Houston also downloaded data dumps to carefully monitor the computer to make sure that it was running normally.

While Ferguson and Hurley focused on computer troubleshooting, Mission Specialists Magnus and Walheim together with the station crew continued to work on cargo transfers between Atlantis and the ISS. Walheim also transferred EMU/airlock items to Atlantis that wouldn't be needed in the post-shuttle era.

Several media interviews happened at about 10:45 UTC. Ferguson and Doug Hurley talked with representatives of CBS Radio, KYW-TV in Philadelphia and Associated Press. Next, beginning at 12:04 UTC all STS-135 crew members talked with WPVI-TV and KYW Radio, both of Philadelphia, and Reuters. At the 45-minute crew news conference, Atlantis crew members and their station colleagues gathered in the Japanese Kibo Laboratory to take questions from news media. Reporters at four NASA centers, NASA headquarters and in Japan participated.

President Barack Obama, at about 16:30 UTC also called the combined Expedition 28 and Atlantis crews.[110] He thanked those who had supported the shuttle program and said that he was proud of all the crew members. Shuttle Commander Chris Ferguson said that all the partners on the station were honored to represent their home countries in this multinational effort and station Flight Engineer Sergei Volkov described the station and shuttle crews, from three nations, as "one big family".[111]

During the Mission Status Briefing, the STS-135 lead flight director, Kwatsi Alibaruho, said that transfers were right on timeline with 70% complete. The crew was ahead of timeline on earlier days but the computer problem caused them to slow down. He further mentioned that the latch on Atlantis's middeck locker for LiOH canisters was broken, and as a result, the entire panel had been fastened to floor with fasteners. The LiOH canisters are used to scrub carbon dioxide from the cabin air inside the shuttle. When Atlantis is docked to the space station, the station Carbon Dioxide Removal Assembly (CDRA)[112] takes care of both the station's and Atlantis's air revitalization. However, when Atlantis flew solo after undocking, LiOH canisters were required. Regarding the GPC-4 issue, Alibaruho said that it was a very infrequent failure, happened before only on STS-9 and the last time a problem occurred on GPC 4 was on Atlantis's STS-71 mission.

July 16 (Flight Day 9 – Cargo transfers)

[edit]

Flight day 9 was the bonus day added by the Mission Management Team earlier on the week as a result of Atlantis having been able to save enough cryogenic oxygen and hydrogen to power its fuel cells an extra day. Throughout the day, the four member STS-135 crew spent more time to move supplies and equipment between the ISS and the Raffaello MPLM.[113]

Early on the day, Commander Ferguson and Pilot Hurley also spent some time working to successfully repair the door that gives the crew access to the LiOH canisters. Mission Specialist Magnus spent about an hour and a half in the morning taking microbial air samples on various locations in the space station. The collected samples will be returned for study and further analysis. Magnus also worked the Japanese Experiment Module Remote Manipulator System (JEMRMS). Mission Specialist Walheim along with station crew member Mike Fossum continued work with spacewalking equipment in the Quest airlock. Some of them will be left on the station, and will be utilized during an upcoming Russian spacewalks on August 3, 2011. Hurley working with station crew member Ron Garan stored some of the cargo in Atlantis's middeck to be returned. Since no astronaut was riding in the mid-deck on the way back, it was expected to be fully packed with 1564 pounds of cargo. Among cargo brought to the space station, 2281 pounds were also in the mid-deck.

The STS-135 crew also provided a recorded message as a tribute to Atlantis, the entire Space Shuttle Program and team. In the message, Ferguson spoke about the U.S. flag displayed behind them that was flown on the first Space Shuttle mission, STS-1. It was flown on this mission to be presented to the space station crew. The flag remained displayed on board the space station until the next crew launched from the U.S. to the International Space Station retrieved it for return to Earth, which was done by the Crew Dragon Demo-2 crew on June 1, 2020.[114][115]

In a video celebrating the centennial of naval aviation, Commander Ferguson and Pilot Hurley also paid tribute to U.S. naval aviators. Among many those who have made significant contributions to the U.S. human space program, Hurley mentioned several names such as Alan Shepard, the first American to fly in space; John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth; Neil Armstrong and Eugene Cernan, the first and last humans to set foot on the Moon; John Young and Robert Crippen, the first pilots of the Space Shuttle; and Ferguson and Hurley, the commander and the pilot of the current (last) shuttle flight.

Just before the crew prepared to go for sleep, CAPCOM Megan McArthur notified them that the flight controllers thought that the GPC-4 failure was caused by a single event upset (teams on the ground listed a Coronal Mass Ejection as one of three potential contributing factors)[116] and that GPC-4 was a healthy machine. Furthermore, she mentioned that the plan was to assign systems management (SM) to GPC-4 the next morning and if no further problems arose, it was to be kept for undocking.

July 17 (Flight Day 10 – Cargo transfers/Off duty)

[edit]

On Flight Day 10, the crew of Atlantis wrapped up the transfer work inside the Raffaello MPLM. During the Mission Status Briefing, Space Station lead Flight Director Chris Edelen said that "They (crew) reached a key milestone today in that the Raffaello logistics module was closed out, all the cargo that (came) up to space station has been transferred over, that was actually completed a couple of days ago, and today they've packed Raffaello with all the return cargo that's going to be coming back to Earth".[117] STS-135 delivered 9,403 pounds (4,265 kg) of cargo in the MPLM up to the space station and the crew packed up 5,666 pounds (2,570 kg) of returning cargo inside the MPLM. The crew also installed the control and power assemblies in the hatch leading into the MPLM. On the next day, the controllers were used to drive the bolts to release the MPLM from Node 2.

At 10:10 UTC, pilot Doug Hurley and Mission Specialist Rex Walheim answered videotaped questions from students at NASA Explorer Schools across the United States. It was the last interactive educational event conducted by a Space Shuttle crew.[118]

After their midday meal, Mission Specialist Sandra Magnus and Commander Chris Ferguson worked a little over an hour continuing to move experiments and equipment to and from Atlantis's middeck. At the end 84% of middeck transfers were completed. The crew transferred a new science refrigerator (GLACIER) from the Shuttle's middeck to the Space Station. Another couple of noteworthy middeck payloads that were transferred included the mass spectrometer in the mass constituent analyzer, a device in the U.S. segment that samples air from different parts of the station to determine its constituents. Flight Engineer Ron Garan removed the broken spectrometer and moved it to Atlantis's middeck for return. The suspect gyroscope in the TVIS treadmill located in the Russian segment removed by Flight Engineer Sergey Alexandrovich Volkov was also placed in the middeck. After completing those transfers, the shuttle crew had most of the afternoon off.

NASA TV also showed a recorded video in which Magnus, a soccer enthusiast and Station Flight Engineer Satoshi Furukawa cheer on their country's women's world cup soccer teams.[119] On July 17, the U.S. team played against Japan, in the 2011 FIFA Women's World Cup final in Hannover, Germany. Japan won the final on a penalty shoot-out following a 2–2 tie after extra time.

July 18 (Flight Day 11 – MPLM return, farewells/Hatch closure)

[edit]The STS-135 crew returned the MPLM back to Atlantis's payload bay on flight day 11, closed the hatches between the Space Station and the Shuttle and prepared for next day's undocking.[120]

Beginning at 5:03 UTC, the hatches separating Raffaello MPLM and the ISS were closed. With station's Canadarm2 locked onto Raffaello, commands were issued at 10:14 UTC to begin the releasing operations of the 16 motorized bolts holding the MPLM in place on the station's Node 2. Arm operators, Mission Specialist Magnus and Pilot Hurley working inside the cupola, un-berthed Raffaello at 10:48 UTC and moved it back to Atlantis's payload bay. The move was completed by around 11:48 UTC. The securing of the Raffaello in the shuttle's payload bay marked the tenth and final transfer of an MPLM in the history of the Space Shuttle program.

Atlantis and Space Station crew members said their goodbyes and closed hatches between the two spacecraft at 14:28 UTC, ending seven days, 21 hours, 41 minutes of joined docked operations.[121]

At the farewell ceremony, Commander Ferguson presented to the station a small U.S. flag that had flown on STS-1. He also presented a shuttle model signed by program officials and the mission's lead shuttle and station flight directors. "What you don't see is the signatures of the tens of thousands who rose to orbit with us over the past 30 years, if only in spirit," Ferguson said.[122]

Ferguson thanked Expedition 28 commander Andrey Borisenko for the hospitality and his crew's help in making the mission a success. Borisenko replied by wishing the shuttle crew a safe trip home and happy landings. Station Flight Engineer Ron Garan especially thanked Magnus for her "load master" activity of moving cargo between the two spacecraft.

Shortly after the crew returned to Atlantis, hatches between the two spacecraft were closed. They carried out tasks to prepare for the undocking from the Space Station. Ferguson and Hurley installed the centerline camera while hatch leak checks were still under way. Hurley and Walheim also checked out the rendezvous tools.

July 19 (Flight Day 12 – Undocking)

[edit]

Space Shuttle Atlantis undocked from the Space Station early on flight day 12, marking the end of shuttle visits to the orbiting outpost.[123] With pilot Douglas Hurley at the control, undocking occurred at 6:28 UTC as the two spacecraft flew through orbital night above the Pacific Ocean east of Christchurch, New Zealand.[124] Shortly after, in keeping with naval tradition, flight engineer Ron Garan rang the station's bell in the Harmony module, and said "Atlantis, departing the International Space Station for the last time."

After undocking, Atlantis moved away, to a station keeping point about 600 feet (180 m) ahead of the ISS. Before beginning a final half-lap unique fly, pilot Doug Hurley paused the shuttle by firing thrusters for a moment and during this time the space station changed its orientation by rotating 90 degrees to the right.[125] That gave the Atlantis crew a good opportunity to take still camera photographs and shoot video of station areas not normally documented in previous shuttle fly-arounds. The images were expected to help experts on the ground to get additional information on the station's conditions. The half-lap fly around which began around 7:30 UTC was completed about 25 minutes later.

Teams in both shuttle and station flight control rooms in Houston were working their last shuttle shift. Commander Ferguson thanked the Orbit 1 team of shuttle flight controllers headed by Flight Director Kwatsi Alibaruho. He urged them to pause a moment on their way out and "make a memory." From the station flight control room, CAPCOM Daniel Tani, told Ferguson that it had been "a pleasure and an honor" to support the mission. "We are proud to be the last of a countless line of mission control teams who have watched while shuttles visited the ISS. The ISS wouldn't be here without the shuttle," noted Tani. "It's been an incredible ride. On behalf of the four of us, we're really appreciative we had the opportunity to work with you on this pivotal mission," replied Ferguson.[126]

At the end of the half-loop, Atlantis did two TI separation burns, the second at 8:18 UTC to move away from the vicinity of the space station.

After their midday meal, Ferguson, Hurley and Mission Specialist Sandra Magnus did the late survey of Atlantis's heat shield, focused on the reinforced carbon carbon (RCC) of the wing leading edges and the nose cap. They used the shuttle's RMS and its 50-foot (15 m) OBSS to look first at the starboard wing, then the nose cap and finally the port wing. The crew completed the inspections at 2:30 UTC. Magnus and ground engineers began reviewing the collected data to verify that shuttle's TPS has received no impact damage from micrometeoroids or space junk during its docked operations or fly-around of the station. At the end of a highly successful day in space, the crew members went to bed at 4:59 UTC.

-

View from Atlantis as the station completes its 90-degree yaw to port

-

Full starboard side view of the station as Atlantis begins its half-loop fly-around

-

Fly-around commences

-

STS-135 final fly-around of the ISS

-

Fly-around almost complete, the view of the port side of the station from Atlantis

July 20 (Flight Day 13 – PicoSat deployment/Landing prep)

[edit]

One more satellite takes its place in the sky,

The last of many that the shuttle let fly.

Magellan, Galileo, Hubble, and more,

Have sailed beyond her payload bay doors.

There've filled science books, and still more to come,

The shuttle's legacy will live on when her flying is done.

We wish PicoSat success in space where it roams,

It can stay up here, but we're going home.

Yes soon for the last time we'll gently touch down,

Then celebrate the shuttle with our friends on the ground.

— Rex Walheim

Flight day 13 was the final full day in space for the STS-135 crew. They spent the day checking out Atlantis′s flight control surfaces and hot-firing its reaction control system (RCS) jets, making sure everything was ready for deorbit.[127] Mission managers cleared Atlantis for re-entry after reviewing results of the late inspection survey of the shuttle's heat shield, performed by the crew on the flight day 12.

Atlantis's crew also deployed an 8.2-lb (3.7-kg), 5×5×10-inch technology demonstration picosatellite, the Pico-Satellite Solar Cell experiment (PSSC-2), into a low Earth orbit at around 360 km,[128] from inside a spring ejection canister in the shuttle's payload bay.[129] The picosatellite relayed data back on the performance of its solar cells, which were based on new technology intended for use on future satellites. PSSC-2, which was deployed at 7:54 UTC, was the 180th and final payload deployed by a Space Shuttle. Shortly after, CAPCOM astronaut Barry Wilmore congratulated the crew from the ground on the successful deployment. Mission specialist Rex Walheim marked the milestone by reciting an original poem. "Outstanding, Rex, we applaud you," Wilmore said amid cheers from the Houston Flight Control Room.[130]

The crew also participated in one last round of interviews with reporters on the ground. At 8:44 UTC, the crew talked with ABC News, CBS News, CNN, Fox News, and NBC News.

Later in the day, the crew finished their final preparations for Atlantis's planned landing. Commander Ferguson and Pilot Hurley practiced landing procedures with a video game-like simulator,[131] the Portable Inflight Landing Operations Trainer (PILOT). At 6:15 UTC, Ferguson, Hurley and Walheim powered up one of the APUs to conduct OPS-8 activities. This process verified the functionality of Atlantis's flight control surfaces, actuating the rudder, speed brakes, wing and tail body flaps which guided the shuttle through the atmosphere. They then stowed the Ku-Band antenna at 10:34 p.m. EDT and went to sleep.

The Empire State Building in New York City paid tribute to 30 years of Space Shuttle flights by lighting up in red, white and blue throughout the night of July 20.[132]

July 21 (Flight Day 14 – Landing)

[edit]

The final day began with the wakeup song "God Bless America" played at 12:29 UTC. According to CAPCOM Shannon Lucid, the song was dedicated to not only the entire crew, but also to all "the men and women who put their heart and soul into the shuttle program for all these years".[133]

The weather outlook for the landing was promising, with 10-mile (16 km) visibility and 1 mph (1.6 km/h) crosswinds.[134][135][136] Flight controllers decided against delaying the landing until daylight, citing the excellent weather conditions.[137][138] The crew was given a "go" to start "fluid loading", which involved drinking large amounts of liquids and salt tablets. The protocol assists the incoming astronauts from space with weightlessness conditions to re-adapt to Earth's gravity.

The de-orbit burn occurred at 4:49:04 a.m. EDT for three minutes and 17 seconds to decelerate the craft over the Indian Ocean near northwestern Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.[134] The shuttle was re-oriented into forward, right-side-up free-flight.[134][137] The Shuttle crew continued its descent and entered the Earth's atmosphere around 5:25 a.m. EDT.[137] Shuttle technicians moved onto the shuttle landing site around 5:35 a.m. EDT.[137] The craft eventually decelerated to coast at 223 miles per hour (359 km/h).[134] The Space Shuttle landed at the Kennedy Space Center on runway 15 at 5:57:00 am EDT. Nose Gear touch down occurred at 5:57:20 am EDT. Wheelstop occurred at 5:57:54 am EDT.[134][135][139]

Recognizing the conclusion of an era, Mission Commentator Rob Navias declared on nose wheel touchdown "Having fired the imagination of a generation, a ship like no other, its place in history secured, the space shuttle pulls into port for the last time. Its voyage, at an end." Just after wheels stop, also recognizing the historical enormity of the final landing, Commander Chris Ferguson said "Mission complete, Houston, After serving the world for over 30 years, the shuttle has earned its place in history, and it has come to a final stop." to which Entry CAPCOM Barry Wilmore replied "We congratulate you, Atlantis, as well as the thousands of passionate individuals across this great space faring nation who truly empowered this incredible spacecraft which for three decades has inspired millions around the globe. Job well done America!" Ferguson replied "The Space Shuttle changed the way we viewed the world. It's changed the way we view our universe. There's a lot of emotion today, but one thing is indisputable: America's not gonna stop exploring. Thank you Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Endeavour and our ship Atlantis. Thank you for protecting us and bringing this program to such a fitting end. God bless The United States of America."

Hundreds turned out at Kennedy Space Center to witness the last landing of a Space Shuttle. An estimated 4,000 shuttle program workers also gathered to watch TV coverage at the Johnson Space Center in Texas. Inside Mission Control, team members shook hands, hugged and took pictures of each other experiencing the historical occasion.

After working through the checklists to safely power down the shuttle, the crew egressed Atlantis into the Crew Transport Vehicle (CTV). Shortly after, the Houston Mission Control Center handed over Atlantis to the landing convoy at the KSC. The crew performed the traditional walk-around of the shuttle after walking down the stairs from the CTV. On the runway, they also met NASA Administrator Charles Bolden, NASA Deputy Administrator Lori Garver, KSC Center Director Robert Cabana, shuttle program manager John Shannon, launch director Mike Leinbach, Atlantis flow manager Angie Brewer, and other NASA officials. Charles Bolden and Commander Ferguson spoke briefly on the tarmac. Ferguson did note that the door to the Waste Collection System in the shuttle's mid-deck flew open during entry. After the speech, the crew got into the AstroVan for the ride to the crew quarters building where they spend the night before returning to Houston the next day.

Atlantis was towed back to Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF-2) where a walk-around for NASA/Kennedy Space Center employees was held. Following the event, the shuttle was returned to OPF-2 vacated by Space Shuttle Discovery on July 13 where technicians processed Atlantis in preparation for the shuttle's retirement as a museum exhibit in the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex.[140]

-

Long range ground track on orbit 200

-

Atlantis and the STS-135 crew touchdown video

-

STS-135 crew inside the orbiter post APU shutdown

-

Atlantis thirty minutes after touchdown

Welcome home ceremonies

[edit]

On July 21, 2011, NASA hosted an employee appreciation event outside OPF-2, with Atlantis parked.[141] Cheryl Hurst, the director of education and external relations at KSC, spoke first and invited Susan Lambert to lead the crowd with the American national anthem. A Pledge of Allegiance followed from KSC children, and NASA Administrator Charles Bolden and KSC Director Robert Cabana spoke to the shuttle program employees. During the event, Rita Wilcoxson and Patricia Stratton were presented with highest NASA honors: the Distinguished Service Medal and the Distinguished Public Service Medal respectively. The citations on both were identical, stating "for continuous outstanding leadership contributions provided to the nation's space shuttle program". A public "welcome home" ceremony was held for the crew at Houston's Ellington Field Hangar 990 on July 22.[142]

Wake-up calls

[edit]NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, and first used music to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[143]

For STS-135, some of the wake-up calls were accompanied by greetings, from either the performing artist or NASA employees.

| Flight Day | Song | Artist | Greeting | Played for | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "Viva la Vida" | Coldplay | Employees at the Marshall Space Flight Center | Douglas Hurley | MP3 WAV Video |

| Day 3 | "Mr. Blue Sky" | Electric Light Orchestra | Christopher Ferguson | MP3 WAV Video | |

| Day 4 | "Tubthumping" | Chumbawamba | Sandra Magnus | MP3 WAV Video | |

| Day 5 | "More" | Matthew West | Rex Walheim | MP3 WAV Video | |

| Day 6 | "Rocket Man" | Elton John | Elton John | STS-135 Crew | MP3 WAV Video |

| Day 7 | "Man on the Moon" (A cappella version) | Michael Stipe | Michael Stipe | STS-135 Crew | MP3 WAV Video |

| Day 8 | "Good Day Sunshine" | The Beatles | Paul McCartney | STS-135 Crew | Video |

| Day 9 | "Run the World (Girls)" | Beyoncé Knowles | Beyoncé Knowles | Sandra Magnus | Video |

| Day 10 | "Celebration" | Kool & the Gang | Employees at the Stennis Space Center | Sandra Magnus | WAV Video |

| Day 11 | "Days Go By" | Keith Urban | Employees at the Johnson Space Center | Rex Walheim | Video |

| Day 12 | "Don't Panic" | Coldplay | Douglas Hurley | Video | |

| Day 13 | "Fanfare for the Common Man" | Aaron Copland | Employees at the Kennedy Space Center | Christopher Ferguson | Video |

| Day 14 | "God Bless America" | Kate Smith | Shannon Lucid on behalf of all previous missions and to the people that made them happen | STS-135 Crew and "for all the men and women who put their hearts and souls into the Shuttle program for all these years" | Video |

See also

[edit]- 2011 in spaceflight

- List of human spaceflights

- List of International Space Station spacewalks

- List of Space Shuttle missions

References

[edit]- ^ "Launch and Landing". NASA. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "STS-135 Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 11, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ "Consolidated Launch Manifest". NASA. Archived from the original on July 5, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Bergin, Chris (August 20, 2010). "NASA managers approve STS-135 mission planning for June 28, 2011 launch". NASA Space flight. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Obama signs Nasa up to new future". BBC News. October 11, 2010.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (June 17, 2011). "STS-135/ULF-7 – The Final Flight's Timeline Takes Shape". NASA space flight. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Dean, James (January 20, 2011). "Atlantis Officially Designated Final Shuttle Mission". Florida Today. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ Bergin, Chris. "NASA managers insist STS-135 will fly – Payload options under assessment". NASA Space Flight.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Additional Shuttle Mission Almost Guaranteed". Universe Today. September 30, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ Carreau, Mark (October 25, 2010). "Panel Says STS-135 Decision Merits Urgency". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on April 20, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ Malik, Tariq (October 27, 2010). "Why does shuttle Discovery look so dirty?". NBC News. Retrieved November 20, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Matthews, Mark K; Block, Robert (October 28, 2010). "Budget cuts could doom extra shuttle launch". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ Svitak, Amy (November 19, 2010). "Bolden Says Extra Shuttle Flight Needed As Hedge Against Additional COTS Delays". Space News. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ "An Act To authorize the programs of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for fiscal years 2011 through 2013, and for other purposes" (PDF). US Government Printing Office. September 29, 2010. p. 53. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Carreau, Mark (April 11, 2011). "USA Receives $436.5 million Shuttle Extension". Aviation Weekly.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Clark, Stephen (April 21, 2011). "Federal budget pays for summer shuttle flight". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "NASA Assigns Crew for Final Launch on Need Shuttle Mission". NASA. September 14, 2010. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (June 22, 2011). "Last Space Shuttle crew practices for 8 July launch". The Washington Post. The Associated Press.

- ^ "Final Mission". Houston Chronicle. April 22, 2011. Archived from the original on April 7, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ "STS-135". Spacefacts. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Stephen Clark (July 15, 2010). "Compromise NASA bill gets bipartisan endorsement". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ Clarke, Stehphen. "House legislation would undo White House's NASA wish list". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (July 22, 2010). "STS-135 Is Almost A Certainty". NASA Watch. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ Stephen Clark (August 6, 2010). "Senate approves bill adding extra space shuttle flight". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ Chris Bergin (August 10, 2010). "Payload planning pre-empts an imminent NASA decision on STS-135". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ Abrams, Jim (September 29, 2010). "NASA bill passed by Congress would allow for one additional shuttle flight in 2011". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ "NASA Administrator Thanks Congress for 2010 Authorization Act Support". NASA. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ Harwood, William (October 11, 2010). "President Obama signs space program agenda into law". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center FAQ". NASA.gov. NASA. November 17, 2000. Archived from the original on July 5, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (February 14, 2011). "NASA managers insist STS-135 will fly – Payload options under assessment".

- ^ Malick, Tariq (January 8, 2014). "International Space Station Gets Life Extension Through 2024". Space.com. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ Since NASA had even before 2009 terminated many contracts with suppliers, shut down many facilities, and terminated or transferred many employees required to keep the Space Shuttles flying, any extension of the shuttle program at this point (for multiple flights after STS-135) would require a substantial portion of the expenses necessary to start the program in the late 1970s. In other words, the NASA Space Shuttle program had already been dismantled to such an extent that large parts of the program would essentially have to be re-developed from scratch.

- ^ Atkeison, Charles (February 14, 2010). "NASA to add extra shuttle flight". SpaceLaunch News.

- ^ "STS-135 Press Kit (PDF)" (PDF). NASA. July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 18, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- ^ "Robotic Refueling Mission (RRM)". NASA. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ^ a b Werner, Debra (April 2, 2010). "NASA Plans To Refuel Mock Satellite at the Space Station". SPACE NEWS. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ Cheung, Ed. "Satellite Servicing Demonstration". edcheung.com. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ "Robotic Refueling Module, Soon To Be Relocated to Permanent Space Station Position". NASA website. August 16, 2011. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Luu, Tim; Ruel, Stephanie; Labrie, Martin (July 1, 2012). "TriDAR Test Results Onboard Final Shuttle Mission, Applications for Future of Non-Cooperative Autonomous Rendezvous & Docking" (PDF). robotics.estec.esa.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2023. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ Gaudin, Sharon (July 8, 2011). "Atlantis blasts off on historic last mission". Computerworld Inc. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Calamia, Matthew (July 8, 2011). "Android Joins IPhone in Space". Mobiledia Corp. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (July 13, 2010). "Right OMS Pod set for re-installation as ET-138 arrives at KSC for STS-134". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (August 24, 2010). "Managers delay STS-134 ET/SRB mate ahead of tank allocation options". NASAspaceflight.com.

- ^ "Final set of shuttle main engines installed". Spaceflightnow.com. December 10, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Ray, Justin (March 29, 2011). "Stacking of final shuttle rocket boosters underway". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ Ray, Justin (April 18, 2011). "Booster stacking finished for final shuttle flight". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ "Case Use HistorySTS-135, June 2011 Flight Set 114" (PDF). Spaceflight Now. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Travis, Matthew (April 18, 2011). "STS-135: External tank is mated to the solid rocket boosters for Space Shuttle Atlantis launch". SpaceflightNews.net. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (April 30, 2011). "Obama visits wounded congresswoman at space center". Space NBC News. Retrieved April 30, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Hall, Mimi (April 29, 2011). "Obama visits Cape Canaveral". USA TODAY. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ Chris Bergin (May 17, 2011). "STS-135: Atlantis heads to VAB for mating with ET-138". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Stephen Clark (May 17, 2011). "Atlantis rolls closer to summer launch". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Moskowitz, Clara (May 17, 2011). "NASA Prepares Shuttle Atlantis for One Final Launch". SPACE.com. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "STS 135 RSS Feed – Atlantis Updates". NASA. June 1, 2011. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ Seshan, Balasubramanyam (June 1, 2011). "NASA Space Shuttle Atlantis Roll Out to Kennedy Space Center's Launch Pad (PHOTOS)". INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS TIMES. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "NASA's Shuttle Atlantis at Launch Pad, Liftoff Practice Set". PR Newswire. June 1, 2011. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ Travis, Matthew (June 1, 2011). "STS-135: STS-135: More of Atlantis on the launch pad ready for the final space shuttle mission". SpaceflightNews.net. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ Travis, Matthew (June 1, 2011). "STS-135: Atlantis sits on the launch pad ready for the final space shuttle mission". SpaceflightNews.net. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (June 15, 2011). "STS-135: ET-138 Tanking Test reveals SSME Fuel Valve issue". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Harwood, William (June 16, 2011). "Atlantis tank inspections, engine valve swap on tap". SPACEflight Now. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Harwood, William (June 22, 2011). "Shuttle tank inspections going well, valve replaced". Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ "External tank inspections proceeding smoothly, fuel valve replaced | Space Shuttle, STS-135, Space News, International Space Station". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ Kremer, Ken (June 18, 2011). "Final Payload for Final Shuttle Flight Delivered to the Launch Pad". UNIVERSE TODAY. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Ray, Justin (June 19, 2011). "Shuttle Atlantis receives payloads for space station". Spaceflight NOW. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Ray, Justin (June 20, 2011). "Shuttle crew comes to town for practice countdown". Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (June 21, 2011). "STS-135: Crew arrives for TCDT as MFV work begins on SSME-3". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ "NASA – Landing". NASA. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Dean, James (July 6, 2011). "Atlantis in great shape for launch, weather permitting". Florida Today. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011.

- ^ "Atlantis Blasts Off on Final Flight for Space Shuttle Program". FOX News Network, LLC. July 8, 2011. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ DeCotis, Mark (July 9, 2011). "Shuttle Atlantis reaches orbit for final time". FOX News Network, LLC. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Davis, Jason (July 8, 2011). "Atlantis lifts off for the shuttle programs final mission". The Planetary Society Blog. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ "Space shuttle Atlantis in historic final lift-off". BBC News. July 8, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ "Shuttle Atlantis reaches orbit for final time". USA Today. July 9, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (June 8, 2011). "STS-135: Tank Camera modification aimed at filming footage of ET-138′s death". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ "Atlantis begins final mission". Space Launch Report. July 8, 2011. Archived from the original on May 17, 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Bergin, Chris (July 8, 2011). "STS-135: Initial Ascent Reviews point to superb launch performance by Atlantis". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved July 8, 2011.