Striptease

A striptease is an erotic or exotic dance in which the performer gradually undresses, either partly or completely, in a seductive and sexually suggestive manner.[1] The person who performs a striptease is commonly known as a "stripper" or an "exotic" or "burlesque" dancer.

The origins of striptease as a performance art are disputed and various dates and occasions have been given from ancient Babylonia to 20th century America. The term "striptease" was first recorded in 1932. In Western countries, the venues where stripteases are performed on a regular basis are now usually called strip clubs, though they may be performed in venues such as pubs (especially in the United Kingdom), theaters and music halls. At times, a stripper may be hired to perform at a bachelor or bachelorette party. In addition to providing adult entertainment, stripping can be a form of sexual play between partners. This can be done as an impromptu event or – perhaps for a special occasion – with elaborate planning involving fantasy wear, music, special lighting, practiced dance moves, or unrehearsed dance moves.

Striptease involves a slow, sensuous undressing. The stripper may prolong the undressing with delaying tactics such as the wearing of additional clothes or putting clothes or hands in front of just undressed body parts such as the breasts or genitalia. The emphasis is on the act of undressing along with sexually suggestive movement, rather than the state of being undressed. In the past, the performance often finished as soon as the undressing was finished, though recently strippers may continue dancing in the nude.[2][3] The costume the stripper wears before disrobing can form part of the act. In some cases, audience interaction can form part of the act, with the audience urging the stripper to remove more clothing, or the stripper approaching the audience to interact with them.

Striptease and public nudity have been subject to legal and cultural prohibitions and other aesthetic considerations and taboos. Restrictions on venues may be through venue licensing requirements and constraints and a wide variety of national and local laws. These laws vary considerably around the world, and even between different parts of the same country. H. L. Mencken is credited with coining the word ecdysiast – from "ecdysis", meaning "to molt" – in response to a request from striptease artist Georgia Sothern, for a "more dignified" way to refer to her profession. Gypsy Rose Lee, one of the most famous striptease artists of all time, approved of the term.[4][5][6]

History

[edit]

The origins of striptease as a performance art are disputed and various dates and occasions have been given from ancient Babylonia to 20th century America. The term "striptease" was first recorded in 1932.[8]

There is a stripping aspect in the ancient Sumerian myth of the descent of the goddess Inanna into the Underworld (or Kur). At each of the seven gates, she removed an article of clothing or a piece of jewelry. As long as she remained in hell, the earth was barren. When she returned, fecundity abounded. Some believe this myth was embodied in the dance of the seven veils of Salome, who danced for King Herod, as mentioned in the New Testament in Matthew 14:6 and Mark 6:21-22. However, although the Bible records Salome's dance, the first mention of her removing seven veils occurs in Oscar Wilde's play Salome, in 1893.

In ancient Greece, the lawgiver Solon established several classes of prostitutes in the late 6th century BC. Among these classes of prostitutes were the auletrides: female dancers, acrobats, and musicians, noted for dancing naked in an alluring fashion in front of audiences of men.[9][10][11] In ancient Rome, dance featuring stripping was part of the entertainments (ludi) at the Floralia, an April festival in honor of the goddess Flora.[12] Empress Theodora, wife of 6th-century Byzantine emperor Justinian is reported by several ancient sources to have started in life as a courtesan and actress who performed in acts inspired from mythological themes and in which she disrobed "as far as the laws of the day allowed". She was famous for her striptease performance of Leda and the Swan.[13] From these accounts, it appears that the practice was hardly exceptional nor new. It was, however, actively opposed by the Christian Church, which succeeded in obtaining statutes banning it in the following century. The degree to which these statutes were subsequently enforced is, of course, opened to question. What is certain is that no practice of the sort is reported in texts of the European Middle Ages.

An early version of striptease became popular in England at the time of the Restoration. A striptease was incorporated into the Restoration comedy The Rover, written by Aphra Behn in 1677. The stripper is a man; an English country gentleman who sensually undresses and goes to bed in a love scene. (However, the scene is played for laughs; the prostitute he thinks is going to bed with him robs him, and he ends up having to crawl out of the sewer.) The concept of striptease was also widely known, as can be seen in the reference to it in Thomas Otway's comedy The Soldier's Fortune (1681), where a character says: "Be sure they be lewd, drunken, stripping whores".[14]

Striptease became standard fare in the brothels of 18th century London, where the women, called "posture girls", would strip naked on tables for popular entertainment.[15]

Striptease was also combined with music, as in the 1720 German translation of the French La Guerre D'Espagne (Cologne: Pierre Marteau, 1707), where a galant party of high aristocrats and opera singers entertain themselves with hunting, play and music in a three-day turn at a small château:

The dancers, to please their lovers the more, dropped their clothes and danced totally naked the nicest entrées and ballets; one of the princes directed the delightful music, and only the lovers were allowed to watch the performances.[16]

An Arabic custom, first noted by French colonialists and described by the French novelist Gustave Flaubert may have influenced the French striptease. The dances of the Ghawazee in North Africa and Egypt consisted of the erotic dance of the bee performed by a woman known as Kuchuk Hanem. In this dance, the performer disrobes as she searches for an imaginary bee trapped within her garments. It is likely that the women performing these dances did not do so in an indigenous context, but rather, in response to the demand for this type of entertainment.[17] Middle Eastern belly dance, also known as oriental dancing, was popularized in the United States after its introduction on the Midway at the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago by a dancer known as Little Egypt.[18]

Some claim the origin of the modern striptease lies in Oscar Wilde's play Salome (play), in 1893. In the Dance of the Seven Veils, the female protagonist dances for King Herod and slowly removes her veils until she lies naked.[19] After Wilde's play and Richard Strauss's operatic version of the same, first performed in 1905, the erotic "dance of the seven veils" became a standard routine for dancers in opera, vaudeville, film and burlesque. A famous early practitioner was Maud Allan, who in 1907 gave a private performance for King Edward VII.

French tradition

[edit]

In the 1880s and 1890s, Parisian shows such as the Moulin Rouge and Folies Bergère were featuring attractive scantily clad women dancing and tableaux vivants. In this environment, an act in the 1890s featured a woman who slowly removed her clothes in a vain search for a flea crawling on her body. The People's Almanac credits the act as the origin of modern striptease.

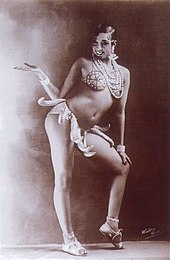

In 1905, the notorious Dutch dancer Mata Hari, later shot as a spy by the French authorities during World War I, was an overnight success from the debut of her act at the Musée Guimet.[20] The most celebrated segment of her act was her progressive shedding of clothing until she wore just a jeweled bra and some ornaments over her arms and head but exposing her pubic region.[21] Another landmark performance was the appearance at the Moulin Rouge in 1907 of an actress called Germaine Aymos, who entered dressed only in three very small shells. In the 1920s and 1930s, Josephine Baker danced topless in the danse sauvage at the Folies, and other such performances were provided at the Tabarin. These shows were notable for their sophisticated choreography and often featuring the women in glitzy sequins and feathers. In his 1957 book Mythologies, semiotician Roland Barthes interpreted this Parisian striptease as a "mystifying spectacle", a "reassuring ritual" where "evil is advertised the better to impede and exorcise it".[22] By the 1960s "fully nude" shows were provided at such places as Le Crazy Horse Saloon.[23]

American tradition

[edit]In the United States, striptease started in traveling carnivals and burlesque theatres, and featured famous strippers such as Gypsy Rose Lee and Sally Rand. The vaudeville trapeze artist Charmion performed a "disrobing" act onstage as early as 1896, which was captured in the 1901 Edison film Trapeze Disrobing Act. Another milestone for modern American striptease is the possibly legendary show at Minsky's Burlesque in April 1925 that inspired the novel and film The Night They Raided Minsky's. Another performer, Hinda Wassau, claimed to have inadvertently invented the striptease in 1928 when her costume was shaken loose during a shimmy dance. Burlesque theatres in New York were prohibited from staging striptease performances in a legal ruling of 1937, leading to the decline of these "grindhouses" (named after the bump 'n grind entertainment on offer).[24] However many striptease stars were able to work in other cities and, eventually, nightclubs.

The 1960s saw a revival of striptease in the form of topless go-go dancing. This eventually merged with the older tradition of burlesque dancing. Carol Doda of the Condor Night Club in the North Beach section of San Francisco is given the credit of being the first topless go-go dancer.[25] The club opened in 1964 and Doda's première topless dance occurred on the evening of June 19 of that year.[26][27] The large lit sign in front of the club featured a picture of her with red lights on her breasts. The club went "bottomless" on September 3, 1969 and began the trend of explicit "full nudity" in American striptease dancing.[28] which was picked up by other establishments such as Apartment A Go Go.[29] San Francisco is also the location of the notorious Mitchell Brothers O'Farrell Theatre. Originally an X-rated movie theater this striptease club pioneered lap dancing in 1980, and was a major force in popularizing it in strip clubs on a nationwide and eventually worldwide basis.[30]

British tradition

[edit]

In Britain in the 1930s, when Laura Henderson began presenting nude shows at the Windmill Theatre, London, censorship regulations prohibited naked girls from moving while appearing on-stage. To get around the prohibition, the models appeared in stationary tableaux vivants.[31][32] The Windmill girls also toured other London and provincial theatres, sometimes using ingenious devices such as rotating ropes to move their bodies round, though strictly speaking, staying within the letter of the law by not moving of their own volition. Another example of the way the shows stayed within the law was the fan dance, in which a naked dancer's body was concealed by her fans and those of her attendants, until the end of her act in when she posed nude for a brief interval whilst standing still.

In 1942, Phyllis Dixey formed her own company of girls and rented the Whitehall Theatre in London to put on a review called The Whitehall Follies.

By the 1950s, touring striptease acts were used to attract audiences to the dying music halls. Arthur Fox started his touring shows in 1948 and Paul Raymond started his in 1951. Paul Raymond later leased the Doric Ballroom in Soho and opened his private members club, the Raymond Revuebar, in 1958. This was one of the first of the private striptease members clubs in Britain.

In the 1960s, changes in the law brought about a boom of strip clubs in Soho with "fully nude" dancing and audience participation.[33] Pubs were also used as a venue, most particularly in the East End with a concentration of such venues in the district of Shoreditch. This pub striptease seems in the main to have evolved from topless go-go dancing.[34] Though often a target of local authority harassment, some of these pubs survive to the present day. An interesting custom in these pubs is that the strippers walk round and collect money from the customers in a beer jug before each individual performance. This custom appears to have originated in the late 1970s when topless go-go dancers first started collecting money from the audience as the fee for going "fully nude".[34] Private dances of a more raunchy nature are sometimes available in a separate area of the pub.[3]

Japan

[edit]Striptease became popular in Japan after the end of World War II. When entrepreneur Shigeo Ozaki saw Gypsy Rose Lee perform, he started his own striptease revue in Tokyo's Shinjuku neighborhood. During the 1950s, Japanese "strip shows" became more sexually explicit and less dance-oriented, until they were eventually simply live sex shows.[35]

Today

[edit]Modern striptease acts typically follow the sequence established in Burlesque: commencing in a dress, baring the upper body first, and continuing to a final reveal of the pelvic region. The traditional performance ended at this point, but modern acts usually continue with a nude dance section. This last element forms the major part of the act in small strip clubs and bars, but performances in larger venues (such as those done by feature dancers) usually place as much weight on the dance in the earlier sections. Striptease dance routines are usually improvised, except for male strippers who generally choreograph their performances and focus as much on the earlier sections as the later.[36]

Recently pole dancing has come to dominate the world of striptease. In the late 20th century, pole dancing was practised in exotic dance clubs in Canada. These clubs grew up to become a thriving sector of the economy. Canadian style pole dancing, table dancing and lap dancing, organized by multi-national corporations such as Spearmint Rhino, was exported from North America to (among other countries) the United Kingdom, the nations of central Europe, Russia and Australia. In London, England a raft of such so-called "lap dancing clubs" grew up in the 1990s, featuring pole dancing on stage and private table dancing, though, despite media misrepresentation, lap-dancing in the sense of bodily contact was forbidden by law.[37]

"Feature shows" are used to generate interest from potential customers who otherwise would not visit the establishment but know the performer from other outlets. A headlining star of a striptease show is referred to as a feature dancer, and is often a performer with credits such as contest titles or appearances in adult films or magazines. The decades-old practice continued through the late 2000s (decade) to the present day with high-profile adult film performers such as Jenna Haze and Teagan Presley scheduling feature shows through the US.

In December 2006, a Norwegian court ruled that striptease is an art form and made strip clubs exempt from value added tax.[38]

New Burlesque

[edit]In the latter 1990s, a number of solo performers and dance groups emerged to create Neo-burlesque, a revival of the classic American burlesque striptease of the early half of the 20th century. New Burlesque focuses on dancing, costumes and entertainment (which may include comedy and singing) and generally eschews full nudity or toplessness. Some burlesquers of the past have become instructors and mentors to New Burlesque performers such as The Velvet Hammer Burlesque and The World Famous Pontani Sisters.[citation needed] The pop group Pussycat Dolls began as a New Burlesque troupe.

Male strippers

[edit]

Until the 1970s, strippers in Western cultures were almost invariably female, performing to male audiences. Since then, male strippers have also become common. Before the 1970s, dancers of both sexes appeared largely in underground clubs or as part of a theatre experience, but the practice eventually became common enough on its own. Well-known troupes of male strippers include Dreamboys in the UK and Chippendales in the US. Male strippers have become a popular option to have at a bachelorette party.

Private dancing

[edit]A variation on striptease is private dancing, which often involves lap dancing or contact dancing. Here the performers, in addition to stripping for tips, also offer "private dances" which involve more attention for individual audience members. Variations include private dances like table dancing where the performer dances on or by customer's table rather than the customer being seated in a couch.

Striptease and the law

[edit]From ancient times to the present day, striptease was considered a form of public nudity and subject to legal and cultural prohibitions on moral and decency grounds. Such restrictions have been embodied in venue licensing regulations, and national and local laws, including liquor licensing restrictions.

United States

[edit]Numerous U.S. jurisdictions have enacted laws regulating the striptease. One of the more notorious local ordinances is San Diego Municipal Code 33.3610,[39] specific and strict in response to allegations of corruption among local officials[40] which included contacts in the nude entertainment industry. Among its provisions is the "six-foot rule", copied by other municipalities, that requires that dancers maintain a six-foot (1.8 m) distance while performing.

Other rules forbid "full nudity". In some parts of the U.S., laws forbid the exposure of female (though not male) nipples, which must be covered by pasties.[2] In early 2010, the city of Detroit banned fully exposed breasts in its strip clubs, following the example of Houston, where a similar ordinance was implemented in 2008.[41] The city council has since softened the rules, eliminating the requirement for pasties[42] but keeping other restrictions. Both cities were reputed to have rampant occurrences of illicit activity linked to striptease establishments.[43][44] For some jurisdictions, even certain postures can be considered "indecent" (such as spreading the legs).[45][self-published source]

United Kingdom

[edit]In Britain in the 1930s, when the Windmill Theatre, London, began to present nude shows, British law prohibited performers moving whilst in a state of nudity.[46] To get around that rule, models appeared naked in stationary tableaux vivants. To keep within the law, sometimes devices were used which rotated the models without them moving themselves. Fan dances were another device used to keep performances within the law. These allowed a naked dancer's body to be concealed by her fans or those of her attendants, until the end of an act, when she posed naked for a brief interval whilst standing stock still, and the lights went out or the curtain dropped to allow her to leave the stage. Changes in the law in the 1960s brought about a boom of strip clubs in Soho, with "fully nude" dancing and audience participation.[33] Following the introduction of the Policing and Crime Act 2009, a local authority licence is required for venues in England and Wales (and later Scotland) where live nude entertainment takes place more than 11 times a year.[47][48]

Iceland

[edit]The legal status of striptease in Iceland was changed in 2010, when Iceland outlawed striptease.[49] Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, Iceland's prime minister said: "The Nordic countries are leading the way on women's equality, recognizing women as equal citizens rather than commodities for sale."[50] The politician behind the bill, Kolbrún Halldórsdóttir, said: "It is not acceptable that women or people in general are a product to be sold."[50]

In popular culture

[edit]Film

[edit]

1940s–1950s

[edit]Mary Martin reprised her famous fur coat striptease of "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" in the 1940 movie Love Thy Neighbor and the 1946 Cole Porter biopic Night and Day.[51]

Lady of Burlesque (known in the UK as Striptease Lady) (1943) based on the novel The G-String Murders (1941), by famous striptease artist Gypsy Rose Lee, stars Barbara Stanwyck as a stripper who gets involved in the investigation of murders at a burlesque house. A play by Gypsy Rose Lee entitled The Naked Genius (1943) was the inspiration for Doll Face (1945), a musical about a burlesque star (Vivian Blaine) who wants to become a legitimate actress.

Gilda (1946), showcases one of the most famous stripteases in cinematic history, performed by Rita Hayworth to "Put the Blame on Mame", though in the event she removes just her gloves, before the act is terminated by a jealous admirer. Murder at the Windmill (1949) (US title: Mystery at the Burlesque), directed by Val Guest is set at the Windmill Theatre, London and features Diana Decker, Jon Pertwee and Jimmy Edwards. Salome (1953) once again features Rita Hayworth doing a striptease act; this time as the famous biblical stripper Salome, performing the Dance of the Seven Veils. According to Hayworth's biographers this erotic dance routine was "the most demanding of her entire career", necessitating "endless takes and retakes".[52] Expresso Bongo (1959) is a British film which features striptease at a club in Soho, London.

1960s–1970s

[edit]In 1960, the film Beat Girl cast Christopher Lee as a sleazy Soho strip club owner who gets stabbed to death by a stripper. Gypsy (1962), features Natalie Wood as the famous burlesque queen Gypsy Rose Lee in her memorable rendition of "Let Me Entertain You". It was re-made for TV in 1993 Starring Bette Midler as Mama Rose and Cynthia Gibb as Gypsy Rose Lee. The Stripper (1963) featured Gypsy Rose Lee, herself, giving a trademark performance in the title role. A documentary film, Dawn in Piccadilly, was produced in 1962 at the Windmill Theatre. In 1964, We Never Closed (British Movietone) depicted the last night of the Windmill Theatre. In 1965, the feature film Viva Maria! starred Brigitte Bardot and Jeanne Moreau as two girls who perform a striptease act and get involved in revolutionary politics in South America.

Also produced in 1965 was Carousella, a documentary about Soho striptease artistes, directed by John Irvin. Another documentary film, which looked at the unglamorous side of striptease, is the 1966 film called,"Strip", filmed at the Phoenix Club in Soho. Secrets of a Windmill Girl (1966) featured Pauline Collins and April Wilding and was directed by Arnold L. Miller. The film has some fan dancing scenes danced by an ex-Windmill Theatre artiste. The Night They Raided Minsky's (1968) gives a possibly legendary account of the birth of striptease at Minsky's Burlesque theatre in New York. In 1968, the sci-fi film Barbarella depicted Jane Fonda stripping in zero-gravity conditions whilst wearing her spacesuit. Marlowe (1969) stars Rita Moreno playing a stripper, in the finale of the movie simultaneously delivering dialogue with the title character and performing a vigorous dance on stage. The Beatles movie Magical Mystery Tour has a scene where all the men on the tour bus go to a gentleman's club and watch a woman strip on stage.

Ichijo's Wet Lust (1972), Japanese director Tatsumi Kumashiro's award-winning Roman porno film featured the country's most famous stripper, Sayuri Ichijō, starring as herself.[53] A British film production of 1976 is the film Get 'Em Off, produced by Harold Baim. Alain Bernardin the owner of the Crazy Horse in Paris directed the film,"Crazy Horse de Paris" [1977]. Paul Raymond's Erotica (1981) stars Brigitte Lahaie and Diana Cochran and was directed by Brian Smedley-Aston. The Dance routines were filmed at the Raymond Revuebar Theatre.

1980s–1990s

[edit]In addition to lesser-known videos such as A Night at the Revuebar (1983), the 1980s also featured mainstream films involving stripping. These included Flashdance (1983), which told the story of blue-collar worker Alexandra (Alex) Owens (Jennifer Beals), who works as an exotic dancer in a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania bar at night and at a steel mill as a welder during the day. Stripping also was part of "genre" films, such as horror thriller Fear City (1984), by Abel Ferrara, about a mass-murderer who terrorizes dancers working at a seedy strip club in Times Square, New York City. The erotic drama 9½ Weeks (1986) depicted Kim Basinger stripping to the tune of "You Can Leave Your Hat On" by Joe Cocker. Stripped to Kill (1987) was an exploitation film from Roger Corman about a lady cop who poses as a stripper to catch a murderer; which was followed by a sequel of the same name. Ladykillers (1988), was a 'whodunnit' murder mystery involving the murders of male strippers by an unknown female assailant. Blaze (1989) features Lolita Davidovitch as notorious stripper Blaze Starr. Starr herself appears in the film in a cameo role.

Massive Attack : Eleven Promos. "Be Thankful For What You've Got" (1992), directed by Baillie Walsh, includes one dance routine by Ritzy Sparkle at the Raymond Revuebar Theatre. Exotica (1994), directed by Atom Egoyan, is set in a Canadian lap-dance club, and portrays a man's (Bruce Greenwood) obsession with a schoolgirl stripper named Christina (Mia Kirshner). Showgirls (1995) was directed by Paul Verhoeven and starred Elizabeth Berkley and Gina Gershon. Striptease (1996), was an adaptation of the novel starring Demi Moore. Barb Wire (1996), starred Pamela Anderson (of Baywatch fame), who performs a wet striptease. The Full Monty (1997) is a story of British ex-steel workers who form a Chippendales-style dance revue and decide to strip naked to make an extra buck. It featured songs including an updated version of David Rose's big hit The Stripper and Tom Jones's version of "You Can Leave Your Hat On". The Players Club (1998) starred LisaRaye as a girl who becomes a stripper to earn enough money to enter college and study journalism.

2000s–present

[edit]Dancing at the Blue Iguana (2000) is a feature film starring Daryl Hannah. The female cast of the film researched the film by dancing at strip clubs and created their parts and their storylines to be as realistic as possible. The Raymond Revuebar the Art of Striptease (2002) is a documentary, directed by Simon Weitzman. Los Debutantes (2003) is a Chilean film set in a strip-club in Santiago. In the Cradle 2 the Grave a 2003 action film a woman named Daria, played by Gabrielle Union performs a striptease to distract a man named Odion, played by Michael Jace from the infiltration of a night club owned by a crime lord named Jump Chambers, played by Chi McBride. Portraits of a Naked Lady Dancer (2004) is a documentary, directed by Deborah Rowe. In Closer (2004), Natalie Portman plays Alice, a young stripper just arrived in London from America. Crazy Horse Le Show (2004) features dance routines from the Crazy Horse, Paris. Mrs Henderson Presents (2005) portrays the erotic dance routines and nude tableau-vivants which featured at the Windmill Theatre before and during World War II. The film Factotum (2005) (by Norwegian director Bent Hamer) concludes with Matt Dillon (in the role of Henry Chinaski - an alter ego of Charles Bukowski, who wrote the novel on which the film is based) having an artistic epiphany whilst watching a stripper in a strip club. I Know Who Killed Me (2007) stars Lindsay Lohan as Dakota Moss, an alluring stripper involved in the machinations of a serial killer, and features a long striptease sequence at a strip club. Planet Terror (2007) stars Rose McGowan as Cherry Darling, a beautiful go-go dancer who aspires to quit her job. In 2009 a DVD called, "Crazy Horse Paris" featuring Dita Von Teese was released. Magic Mike (2012) features a male stripper Mike Lane (Channing Tatum) guiding a younger male stripper in his first steps into stripping in clubs.

Television

[edit]- BBC Panorama (1964) episode produced for the last night of the Windmill Theatre in 1964. Richard Dimbleby interviews Sheila van Damm.

- Get Smart (1967) CONTROL scientist Dr. Steele also works as a stripper, with her lab located at the striptease theatre.

- "If it Moves it's Rude-The Story of the Windmill Theatre" (1969). A BBC television documentary on the Windmill Theatre.

- For the Record: Paul Raymond (1969), the British stripclub owner Paul Raymond told his own story, on LWT.

- Peek a Boo (1978), alternative name The One and Only Phyllis Dixey, stars Lesley-Anne Down, Christopher Murney, Michael Elphick, Elaine Paige and Patricia Hodge. Drama documentary on Phyllis Dixey.

- 'Allo 'Allo! Helga frequently does a striptease in front of General Von Klinkerhoffen.

- Neighbours (1985) The character of Daphne is originally a stripper at Des's bucks party, and eventually goes on to marry him.

- Married... with Children (1987–1997) often featured Al Bundy, Jefferson D'Arcy, and the NO MA'AM crew spending a night at the Nudie Bar.

- Soho Stories (1996) BBC2. A series of 12 documentary programmes screened from October 28, 1996 to November 20, 1996. Some programmes featured the Raymond Revuebar Theatre.

- Humor es...los comediantes (1999) Televisa. In her first appearance on this series, Aida Pierce portrayed her elderly alter ego, Virginola, who drinks a bottle of youth serum, and then performs a striptease, taking off her sweater, skirt, scarf, and even her wig, revealing a black sheer bodysuit and pants...and Pierce herself. Pierce began cohosting the series the next year.

- The Sopranos (1999–2007). Business was often conducted at the Bada Bing strip club.

- Normal, Ohio (2000)

- Stripsearch (2001–), an ongoing Australian reality television show which centers around the training of male strippers.

- Sex in the 70s-The King of Soho (2005), ITN. A television documentary on Paul Raymond.A longer version of the documentary was produced in 2008 after the death of Paul Raymond under the title,"Soho Sex King-The Paul Raymond Story".

- in Sos mi vida (2006), there were two striptease scenes which performed by Natalia Oreiro and Facundo Arana.

- Degrassi: The Next Generation (2007), In the two part season 6 finale titled Don't You Want Me, Alex Nunez resorts to stripping after her mother and herself do not have enough money to pay the rent on their apartment.

- Various episodes of the Law & Order series have the cast conducting interviews in strip clubs.

- True Stories: Best Undressed (2010) A documentary about the Miss Nude Australia Contest which is for dancers. Partly filmed from the Crazy Horse Revue, Adelaide, Australia. Screened 22-6-2010 on Channel 4.

- Confessions of a Male Stripper (2013), The Dreamboys were featured in an hour-long documentary special on Channel 4 exploring the life of male strippers.

Theatre

[edit]- Mary Martin became a star with her fur coat striptease performances of "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" in Cole Porter's Broadway musical Leave It to Me![51]

- The Full Monty (2000) is an Americanized stage adaptation of the 1997 British film of the same name, in which a group of unemployed male steelworkers put together a strip act at a local club.

- Jekyll and Hyde (1997). The character of Lucy Harris (originally portrayed by Linda Eder) works as a prostitute and stripper in a small London club called The Red Rat, where she meets a multi-dimension man named Doctor Henry Jekyll, who turns into his evil persona Mr. Edward Hyde. Lucy performs the song ‘Bring on the Men’ during a show at the Red Rat (which was later replaced with ‘Good ‘n’ Evil’ in the Broadway production, some claiming ‘Bring on the Men’ was too ‘risqué’.).

- Ladies Night is a New Zealand stage comedy about unemployed male workers who put on a strip show at a club as a way to raise some money. A version was also written for the United Kingdom. There are many parallels with The Full Monty, although Ladies Night predates that film.

- Barely Phyllis is a play about Phyllis Dixey which was first staged at the Pomegranate Theatre, Chesterfield in 2009.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Richard Wortley (1976) A Pictorial History of Striptease: 11.

- ^ a b Richard Wortley (1976) A Pictorial History of Striptease.

- ^ a b Clifton, Lara; Ainslie, Sarah; Cook, Julie (2002). Baby Oil and Ice: Striptease in East London. Do-Not Press. ISBN 9781899344857.

- ^ "Fathers I Have Known – H.L. Mencken, H. Allen Smith" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2004-12-13.

- ^ Mencken, Henry Louis (1923). The American language: an inquiry into the development of English in the United States (3 ed.). A. A. Knopf.

- ^ "Gypsy and the Ecdysiasts". May 21, 2010. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Image from Der spanische, teutsche, und niederländische Krieg oder: des Marquis von ... curieuser Lebens-Lauff, vol. 2 (Franckfurt/ Leipzig, 1720), p.238

- ^ "First known use of striptease 1932". Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Zaplin, Ruth (1998). Female offenders: critical perspectives and effective interventions. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-8342-0895-7.

- ^ Jeffreys, Sheila (2009). The industrial vagina: the political economy of the global sex trade. Taylor & Francis. pp. 86–106. ISBN 978-0-415-41233-9.

- ^ Baasermann, Lugo (1968). The oldest profession: a history of prostitution. Stein and Day. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0-450-00234-2.

- ^ As described by Ovid, Fasti 4.133ff.; Juvenal, Satire 6.250–251; Lactantius, Divine Institutes 20.6; Phyllis Culham, "Women in the Roman Republic," in The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 144; Christopher H. Hallett, The Roman Nude: Heroic Portrait Statuary 200 B.C.–A.D. 300 (Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 84.

- ^ Evans, James Allan (2003). The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. University of Texas Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-292-70270-7.

- ^ Robert Hendrickson (1997) QPB Encyclopedia of Word and Phrase Origins. New York, Facts on File, Inc: 227

- ^ "The Shocking History of striptease". Archived from the original on 2013-08-16.

- ^ The German text reads "Die Tänzerinnen, um ihren Amant desto besser zu gefallen, zohen ihre Kleider ab, und tantzten gantz nackend die schönsten Entrèen und Ballets; einer von den Printzen dirigirte dann diese entzückende Music, und stunde die Schaubühne niemand als diesen Verliebten offen.", Der spanische, teutsche, und niederländische Krieg oder: des Marquis von ... curieuser Lebens-Lauff, Bd. 2 (Franckfurt/ Leipzig, 1720), S.238, recapitulated in Olaf Simons, Marteaus Europa oder der Roman, bevor er Literatur wurde (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001), pp.617–635.

- ^ Parramore, Lynn (2008). Reading the Sphinx: Ancient Egypt in Nineteenth-Century Literary Culture. Macmillan. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-230-60328-8.

- ^ Carlton, Donna (1994). Looking for Little Egypt. IDD Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-9623998-1-7.

- ^ Toni Bentley (2002) Sisters of Salome: 31

- ^ Denise Noe. "Mata Hari is Born". www.crimelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Mata Hari Archived August 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Striptease, in Mythologies by Roland Barthes, translated by Annette Lavers. Hill and Wang, bar New York, 1984

- ^ Richard Wortley (1976) A Pictorial History of Striptease: 29-53

- ^ "The New Victory Cinema". Newvictory.org. 1995-12-11. Archived from the original on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ "Nudity, Noise Pay Off in Bay Area Night Clubs", Los Angeles Times, February 14, 1965, p. G5.

- ^ California Solons May Bring End To Go-Go-Girl Shows In State, Panama City News, September 15, 1969, p. 12A.

- ^ "Naked Profits". The New Yorker. July 12, 2004. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ "1964". Answers.com. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ Arguments Heard On Nude Dancing, Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1969, p. C1.

- ^ Lap Victory. How a DA's decision to drop prostitution charges against lap dancers will change the sexual culture of S.F. -- and, perhaps, the country. Archived 2009-04-06 at the Wayback Machine SF Weekly, 8 September 2004

- ^ Vivien Goldsmith, "Windmill: always nude but never rude", Daily Telegraph, 24 November 2005

- ^ "Windmill Girls meet for reunion and remember dancing days in old Soho". Islington Tribune.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Murray (2005). Naked Jungle: Soho Stripped Bare. Silverback Press. ISBN 9780954944407.

- ^ a b Martland, Bill (March 2006). It Started With Theresa. Lulu Enterprises Incorporated. ISBN 9781411651784. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ Shteir, Rachel (2004). Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-19-512750-8.

- ^ Liepe-Levinson, Katherine (2003). Strip Show: Performances of Gender and Desire. Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 9781134688692.

- ^ Vlad Lapidos (1996) The Good Striptease Guide to London. Tredegar Press.

- ^ BBC News. Stripping is art, Norway decides. December 6, 2006.

- ^ "Ch03Art03Division36" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ Philip J. LaVelle (19 July 2005). "More bad news? What else is new? – Blemishes keep city in national spotlight". The San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ "Houston topless clubs lose case, may respond to Supreme Court with pasties". Canada.com. 2008-03-29. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ "Detroit Passes New Strip Club Rules - Detroit Local News Story - WDIV Detroit". Archived from the original on June 9, 2011.

- ^ Time Waster (2011-06-06). "Another Houston Strip Club Raided". The Smoking Gun. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ Fantasee Blu (11 November 2009). "Detroit City Council To Vote On Strip Club Restrictions". Detroit: Kiss-FM. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ "A Gentleman" (2010) The Stripping Question Xlibris, p.2 ISBN 9781450037556[self-published source]

- ^ Martin Banham, "The Cambridge guide to theatre", Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-521-43437-8, page 803

- ^ "Sexual Entertainment Venues: Guidance for England and Wales" (PDF). Home Office. March 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Orbach, Max (2008-06-11). "Tough new rules on strip club openings". Echo. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ "Iceland Review Online: Daily News from Iceland, Current Affairs, Business, Politics, Sports, Culture". Icelandreview.com. 2010-03-24. Archived from the original on 2013-12-01. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ a b Clark, Tracy (2010-03-26). "Iceland's stripping ban - Broadsheet". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ a b Roy Hemming (1999), The melody lingers on: the great songwriters and their movie musicals, Newmarket Press, ISBN 978-1-55704-380-1

- ^ Edward Z. Epstein and Joseph Morella (1984) Rita: The Life of Rita Hayworth. London, Comet: 200

- ^ "Ichijo Sayuri: Nureta Yokujo". Allmovie. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Toni Bentley, 2002. Sisters of Salome.

- Bernson, Jessica (2016). The Naked Result: How Exotic Dance Became Big Business. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199846207.

- Arthur Fox, 1962. Striptease with the Lid Off. Empso Ltd., Manchester.

- Arthur Fox, 1962. "Striptease Business". Empso Ltd., Manchester.

- Murray Goldstein, 2005. Naked Jungle - Soho Stripped Bare. Silverback Press.

- Lucinda Jarrett, 1997. Stripping in Time: a history of erotic dancing. Pandora (HarperCollins), London.

- Holly Knox, 1988. Sally Rand, From Films to Fans. Maverick Publications, Bend, U.S.A. ISBN 0-89288-172-0.

- Michelle Lamour, 2006. The Most Naked Woman. Utopian Novelty Company, Chicago, Ill.

- Philip Purser and Jenny Wilkes, 1978. The One and Only Phyllis Dixey. Futura Publications, London. ISBN 0-7088-1436-0.

- Roye, The Phyllis Dixey Album (The Spotlight on Beauty Series No. 3.) The Camera Studies Club, Elstree.

- Roye, 1942. Phyllis in Censorland. The Camera Studies Club, London.

- Andy Saunders, 2004. Jane: a Pin Up at War. Leo Cooper, Barnsley. ISBN 1-84415-027-5. (Jane (Chrystabel Leighton-Porter) was a well known cartoon and photographic model. Jane was also a tableau model and appeared in theatres in Britain.)

- Rachel Shteir, 2004. Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show. Oxford University Press.

- A. W. Stencell, 1999. Girl Show: Into the Canvas World of Bump and Grind. ECW Press, Toronto, Canada. ISBN 1-55022-371-2.

- Tempest Storm & Bill Boyd, 1987. Tempest Storm; The Lady is a Vamp. Peacetree, U.S.A.

- Sheila van Damm, 1957. No Excuses. Putnam, London

- Sheila van Damm, 1967. We Never Closed. Robert Hale, London. ISBN 0-7091-0247-X.

- Vivian van Damm, 1952. Tonight and Every Night. Stanley Paul, London.

- Antonio Vianovi, 2002. Lili St Cyr: Her Intimate Secrets: Profili Album. Glamour Associated, Italy.

- Dita Von Teese, 2006. Burlesque and the Art of Striptease. Regan Books, New York, NY. ISBN 0-06-059167-6

- Paul Willetts, 2010 (August). Members Only: the Life and Times of Paul Raymond. Serpent's Tail Ltd., London. ISBN 9781846687150.

- Richard Wortley, 1969. Skin Deep in Soho. Jarrolds Publishers, London. ISBN 0-09-087830-2

- Richard Wortley, 1976. The Pictorial History of Striptease. Octopus Books, London. (Later edition by the Treasury Press, London. ISBN 0-907407-12-9.)

External links

[edit] Media related to Striptease at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Striptease at Wikimedia Commons