Streptococcus oralis

| Streptococcus oralis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Lactobacillales |

| Family: | Streptococcaceae |

| Genus: | Streptococcus |

| Species: | S. oralis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Streptococcus oralis Bridge and Sneath 1982[1]

| |

Streptococcus oralis is a Gram positive viridans streptococcus of the Streptococcus mitis group.[2][3] S. oralis is one of the pioneer species associated with eubiotic dental pellicle biofilms, and can be found in high numbers on most oral surfaces.[4][5] It has been, however, found to be an opportunistic pathogen as well.[2]

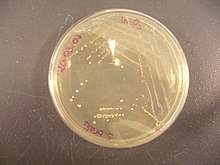

Individual cells of S. oralis are arranged into characteristic long chains when viewing subcultures under a microscope.[6] It is a non-motile, non-sporulating facultative anaerobe.[7] The optimal culturing temperature range for S. oralis is 35 - 37°C, with growth observed between 10 - 45°C.[7][8][9] Blood agars selective for streptococci, such as brain heart infusion blood agar, are optimal for culturing S. oralis as these plates highlight its α-haemolysis, but nutrient agars such as trypticase soy agar or Wilkins-Chalgren anaerobe agar can support its growth also.[7][8] S. oralis colonies are white, grey, or colourless; translucent; smooth; entire; raised cluster colonies 0.5-2.0 mm in diameter.[9]

S. oralis is catalase negative and oxidase negative.[7] Strains of S. oralis produce neuraminidase and cannot bind α-amylase.[2][7][8] S. oralis is also acid-sensitive, producing alkaline metabolites to ameliorate its niche.[10]

Role in the oral microbiome

[edit]S. oralis is one of a few pioneer species important in early colonisation of the dental pellicle, where it establishes an eubiotic biofilm believed to be protective for teeth.[5][10][11] It discourages competition by other mouth commensals and pathobionts such as S. mutans and Candida albicans implicated in dysbiotic biofilm formation by sequestering (i.e. accumulating and storing) nutrients and releasing metabolites such as H2O2.[5][12] A recent study by Leo et al. has investigated the potential mechanism employed by S. oralis to achieve biofilm establishment.[11] The study described a novel protease therein named MdpS released extracellularly by S. oralis, which directly breaks down MUC5B, an O-glycosylated protein which constitutes the majority of the dental pellicle.[11] Through this interaction, S. oralis may be able to adhere to dental enamel, acquire nutrients from the broken-down MUC5B molecules, and hence establish the biofilm.[11] The genome for this protease is highly conserved amongst the S. mitis group, but is notably distant from the genome of S. mutans, indicating that they occupy competing niches;[11] MdpS is active at pH 6.5-7.5, whilst S. mutans modifies the pH of its environment to 4.5-5.5 by releasing lactic acid.[11][13] MdpS also showed mild immunomodulatory activity, as the study found that it can cleave IgA to a certain extent.[11] Since other IgA proteases of S. oralis have been described in prior literature, immunomodulation may be another adaptation advantageous for establishing the eubiotic biofilm.[14] However, further research is required to establish these mechanisms further.

Opportunistic pathogenicity

[edit]S. oralis has been implicated in opportunistic cases of bacteraemia, septicaemia and meningitis in immunocompromised patients, usually in relation to chronic dental disease and/or prior treatment which could provide a point of entry.[2][3][6][7][8][13][15][16][17][18] The infection most associated with S. oralis is infective endocarditis.[17]

Natural genetic transformation

[edit]Like other streptococci and oral commensals, S. oralis also shows high genetic diversity.[15] As such, it is competent for natural genetic transformation.[19] S. oralis cells are able to take up exogenous DNA and incorporate exogenous sequence information into their genomes by homologous recombination.[20] These bacteria can employ a predatory fratricidal mechanism for active acquisition of homologous DNA.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ Parte, A.C. "Streptococcus". LPSN.

- ^ a b c d Byers, H.L.; Tarelli, E.; Homer, K.A.; Beighton, D. (2000-03-01). "Isolation and characterisation of sialidase from a strain of Streptococcus oralis". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 49 (3): 235–244. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-49-3-235. ISSN 0022-2615.

- ^ a b Patterson, Maria Jevitz (1996), Baron, Samuel (ed.), "Streptococcus", Medical Microbiology (4th ed.), Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2, PMID 21413248, retrieved 2024-02-26

- ^ Mattos-Graner, Renata O.; Duncan, Margaret J. (2017-01-01). "Two-component signal transduction systems in oral bacteria". Journal of Oral Microbiology. 9 (1): 1400858. doi:10.1080/20002297.2017.1400858. ISSN 2000-2297. PMC 5706477. PMID 29209465.

- ^ a b c Borisy, Gary G.; Valm, Alex M. (June 2021). Darveau, Richard; Curtis, Mike (eds.). "Spatial scale in analysis of the dental plaque microbiome". Periodontology 2000. 86 (1): 97–112. doi:10.1111/prd.12364. ISSN 0906-6713. PMC 8972407. PMID 33690940.

- ^ a b "Streptococcus oralis". microbe-canvas.com. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ a b c d e f "ABIS Encyclopedia". tgw1916.net. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ a b c d "Streptococcus oralis - microbewiki". microbewiki.kenyon.edu. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ a b Hardie, Jeremy M.; Whiley, Robert A. (2006), Dworkin, Martin; Falkow, Stanley; Rosenberg, Eugene; Schleifer, Karl-Heinz (eds.), "The Genus Streptococcus—Oral", The Prokaryotes: Volume 4: Bacteria: Firmicutes, Cyanobacteria, New York, NY: Springer US, pp. 76–107, doi:10.1007/0-387-30744-3_2, ISBN 978-0-387-30744-2, retrieved 2024-02-26

- ^ a b Zhu, Yimei; Wang, Ying; Zhang, Shuyang; Li, Jiaxuan; Li, Xin; Ying, Yuanyuan; Yuan, Jinna; Chen, Keda; Deng, Shuli; Wang, Qingjing (2023-05-18). "Association of polymicrobial interactions with dental caries development and prevention". Frontiers in Microbiology. 14. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1162380. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 10232826. PMID 37275173.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leo, Fredrik; Lood, Rolf; Thomsson, Kristina A.; Nilsson, Jonas; Svensäter, Gunnel; Wickström, Claes (2024-01-18). "Characterization of MdpS: an in-depth analysis of a MUC5B-degrading protease from Streptococcus oralis". Frontiers in Microbiology. 15. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2024.1340109. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 10830703. PMID 38304711.

- ^ Choi, Allen; Dong, Kevin; Williams, Emily; Pia, Lindsey; Batagower, Jordan; Bending, Paige; Shin, Iris; Peters, Daniel I.; Kaspar, Justin R. (2023-08-21). Human Saliva Modifies Growth, Biofilm Architecture and Competitive Behaviors of Oral Streptococci (Report). Microbiology. doi:10.1101/2023.08.21.554151. PMC 10473590. PMID 37662325.

- ^ a b Wang, Xiuqing; Li, Jingling; Zhang, Shujun; Zhou, Wen; Zhang, Linglin; Huang, Xiaojing (2023-03-06). "pH-activated antibiofilm strategies for controlling dental caries". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 13. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2023.1130506. ISSN 2235-2988. PMC 10025512. PMID 36949812.

- ^ Poulsen, Knud; Reinholdt, Jesper; Jespersgaard, Christina; Boye, Kit; Brown, Thomas A.; Hauge, Majbritt; Kilian, Mogens (January 1998). "A Comprehensive Genetic Study of Streptococcal Immunoglobulin A1 Proteases: Evidence for Recombination within and between Species". Infection and Immunity. 66 (1): 181–190. doi:10.1128/IAI.66.1.181-190.1998. ISSN 0019-9567. PMC 107875. PMID 9423856.

- ^ a b Do, Thuy; Jolley, Keith A.; Maiden, Martin C. J.; Gilbert, Steven C.; Clark, Douglas; Wade, William G.; Beighton, David (2009-08-01). "Population structure of Streptococcus oralis". Microbiology. 155 (8): 2593–2602. doi:10.1099/mic.0.027284-0. ISSN 1350-0872. PMC 2885674. PMID 19423627.

- ^ Bochud, P.- Y.; Eggiman, P.; Calandra, T.; Van Melle, G.; Saghafi, L.; Francioli, P. (1994-01-01). "Bacteremia Due to Viridans Streptococcus in Neutropenic Patients with Cancer: Clinical Spectrum and Risk Factors". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 18 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1093/clinids/18.1.25. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 8054434.

- ^ a b Nahhal, Sarah B.; Sarkis, Patrick; Zakhem, Aline El; Arnaout, Mohammad Samir; Bizri, Abdul Rahman (2023-04-03). "Streptococcus oralis pulmonic valve endocarditis: a case report and review of the literature". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 17 (1): 120. doi:10.1186/s13256-023-03835-y. ISSN 1752-1947. PMC 10068205. PMID 37009863.

- ^ Matsumoto-Nakano, M. (2014-01-01), "Dental Caries", Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, Elsevier, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801238-3.00001-5, ISBN 978-0-12-801238-3, retrieved 2024-02-26

- ^ Reichmann, Peter; Nuhn, Michael; Denapaite, Dalia; Brückner, Reinhold; Henrich, Bernhard; Maurer, Patrick; Rieger, Martin; Klages, Sven; Reinhard, Richard; Hakenbeck, Regine (June 2011). "Genome of Streptococcus oralis Strain Uo5▿". Journal of Bacteriology. 193 (11): 2888–2889. doi:10.1128/JB.00321-11. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 3133139. PMID 21460080.

- ^ a b Johnsborg O, Eldholm V, Bjørnstad ML, Håvarstein LS (2008). "A predatory mechanism dramatically increases the efficiency of lateral gene transfer in Streptococcus pneumoniae and related commensal species". Mol. Microbiol. 69 (1): 245–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06288.x. PMID 18485065. S2CID 30923996.

Note

[edit]- Marsh, Philip; Michael V. Martin (1999). Oral microbiology. Oxford [England]: Wright. ISBN 978-0-7236-1051-9.

External links

[edit]- Type strain of Streptococcus oralis at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase

- Streptococcus oralis: Introduction, Morphology, Pathogenicity, Lab Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention, and Keynotes at Universe84a