Story of Ahikar

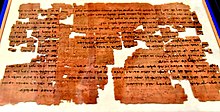

The Story of Aḥiqar, also known as the Words of Aḥiqar, is a story first attested to in Imperial Aramaic from the fifth century BCE on papyri from Elephantine, Egypt, that circulated widely in the Middle and the Near East.[1][2][3] It has been characterised as "one of the earliest 'international books' of world literature".[4]

The principal character, Aḥiqar, might have been a chancellor to the Assyrian Kings Sennacherib and Esarhaddon. Only a Late Babylonian cuneiform tablet from Uruk (Warka) mentions an Aramaic name Aḫu’aqār.[5] His name is written in Imperial Aramaic אחיקר and in Syriac ܐܚܝܩܪ and is transliterated as Aḥiqar, Arabic حَيْقَار (Ḥayqār), Greek Achiacharos, and Slavonic Akyrios, with variants on that theme such as Armenian Խիկար (Xikar) and Ottoman Turkish Khikar, a sage known in the ancient Near East for his outstanding wisdom.[6]

It is known as TAD C1.1, and catalogued as Berlin P. 13446A-H, K-L (Egyptian Museum of Berlin) and Pap. No. 3465 = J. 43502 (Egyptian Museum of Cairo).[3]

Narrative

[edit]In the story, Ahikar is a mythical chancellor to the Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Esarhaddon.[7] Having no child of his own, he adopted his nephew Nadab/Nadin, and raised him to be his successor. Nadab/Nadin ungratefully plotted to have his elderly uncle murdered, and persuades Esarhaddon that Ahikar has committed treason. Esarhaddon orders Ahikar be executed in response, and so Ahikar is arrested and imprisoned to await punishment. However, Ahikar reminds the executioner that the executioner had been saved by Ahikar from a similar fate under Sennacherib, and so instead the executioner kills a different prisoner, and pretends to Esarhaddon that it is the body of Ahikar.

The remainder of the early texts do not survive beyond this point, but it is thought probable that the original ending had Nadab/Nadin being executed while Ahikar is rehabilitated. Later texts portray Ahikar coming out of hiding to counsel the Egyptian king on behalf of Esarhaddon, and then returning in triumph to Esarhaddon. In the later texts, after Ahikar's return, he meets Nadab/Nadin and is very angry with him, and Nadab/Nadin then dies.

Origins and development

[edit]At Uruk (Warka), a Late Babylonian cuneiform text from the second century BCE was found that mentions the Aramaic name A-ḫu-u’-qa-a-ri of an ummānu "sage" Aba-enlil-dari (probably to be read in Babylonian as Mannu-kīma-enlil-ḫātin) under Esarhaddon (seventh century BCE).[5] There are also references to one or more people named Ahī-yaqar in cuneiform texts from the time of Sennacherib and Esarhaddon, although the identification of this person (or people) with the sage Ahiqar is uncertain.[8] The literary text of the sage Aḥiqar might have been composed in Aramaic in Mesopotamia, probably around the late seventh or early sixth century BCE. The first attestation are several papyrus fragments of the fifth century BCE from the ruins of the Jewish military colony on the island Elephantine, Egypt.[9][10] The narrative of the initial part of the story is expanded greatly by the presence of a large number of wise sayings and proverbs that Ahiqar is portrayed as speaking to his nephew. It is suspected by most scholars that these sayings and proverbs were originally a separate document, as they do not mention Ahiqar. Some of the sayings are similar to parts of the Biblical Book of Proverbs, others to the deuterocanonical Wisdom of Sirach, and others still to Babylonian and Persian proverbs. The collection of sayings is in essence a selection from those common in the Middle East at the time.[11]

In the Koine Greek Book of Tobit (second or third century BCE), Tobit has a nephew named Achiacharos (Αχιαχαρος, Tobit 1:21) in royal service at Nineveh. It was pointed out by scholar George Hoffmann in 1880 that Ahikar and the Achiacharus of Tobit are identical. In the summary of W. C. Kaiser, Jr.:

'chief cupbearer, keeper of the signet, and in charge of administrations of the accounts under King Sennacherib of Assyria', and later under Esarhaddon (Tob. 1:21–22 NRSV). When Tobit lost his sight, Ahikar [Αχιαχαρος] took care of him for two years. Ahikar and his nephew Nadab [Νασβας] were present at the wedding of Tobit's son, Tobias (2:10; 11:18). Shortly before his death, Tobit said to his son: 'See, my son, what Nadab did to Ahikar who had reared him. Was he not, while still alive, brought down into the earth? For God repaid him to his face for this shameful treatment. Ahikar came out into the light, but Nadab went into the eternal darkness, because he tried to kill Ahikar. Because he gave alms, Ahikar escaped the fatal trap that Nadab had set for him, but Nadab fell into it himself, and was destroyed' (14:10 NRSV).[12]

The Codex Sinaiticus Greek Text, which the New Revised Standard Version follows, has "Nadab." The Greek Text of the Codices Vaticanus and Alexandrinus calls this person "Aman".

It has been contended that there are traces of the legend even in the New Testament, and there is a striking similarity between it and the Life of Aesop by Maximus Planudes (ch. xxiii–xxxii). An eastern sage Achaicarus is mentioned by Strabo.[13] It would seem, therefore, that the legend was undoubtedly oriental in origin, though the relationship of the various versions can scarcely be recovered.[14] Elements of the Ahikar story have also been found in Demotic Egyptian.[1][15] British classicist Stephanie West has argued that the story of Croesus in Herodotus as an adviser to Cyrus the Great is another manifestation of the Ahiqar story.[16] A full Greek translation of the Story of Ahikar was made at some point, but it does not survive. It was, however, the basis for translations into Old Slavonic and Romanian.[15]

There are five surviving Classical Syriac recensions of the Story and evidence for an older Syriac version as well. The latter was translated into Armenian and Arabic. Some Ahiqar elements were transferred to Luqman in the Arabic adaptations. The Georgian and Old Turkic translations are based on the Armenian, while the Ethiopic is derived from the Arabic, influence of which is also apparent in Suret versions now.[15]

Legacy

[edit]In modern folkloristics, the story of Achikar gives its name, in the international Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, to tale type ATU 922A, Achikar (or Achiqar).[17][18][19]

Editions and translations

[edit]- Eduard Sachau, Aramäische Papyrus und Ostraca aus einer jüdischen Militärkolonie (Leipzig: J. C. Hindrichs, 1911), pp. 147–182, pls. 40–50.

- The Story of Aḥiḳar from the Aramaic, Syriac, Arabic, Armenian, Ethiopic, Old Turkish, Greek and Slavonic Versions, ed. by F. C. Conybeare, J. Rendel Harrisl Agnes Smith Lewis, 2nd edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913) archive.org

- A. Cowley, "The Story of Aḥiḳar," in Aramaic Papyri of the Fifth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1923), pp. 204–248.

- Platt, Rutherford H. Jr., ed. (1926). The forgotten books of Eden. New York, NY: Alpha House. pp. 198–219. (audiobook)

- The Say of Haykar the Sage translated by Richard Francis Burton

- James M. Lindenberger, The Aramaic Proverbs of Ahiqar (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

- James M. Lindenberger, Ahiqar. A New Translation and Introduction, in James H. Charlesworth (1985), The Old Testament Pseudoepigrapha, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company Inc., Volume 2, ISBN 0-385-09630-5 (Vol. 1), ISBN 0-385-18813-7 (Vol. 2), pp. 494–507.[20]

- Ingo Kottsieper, Die Sprache der Aḥiqarsprüche (= Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die altestamentliche Wissenschaft, 194) (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1990). ISBN 3-11-012331-2

- Bezalel Porten, Ada Yardeni, "C1.1 Aḥiqar," in Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt, vol. 3 (Jerusalem, 1993), pp. 23–57. ISBN 965-350-014-7

Literature

[edit]- Bledsoe, Seth. The Wisdom of the Aramaic Book of Ahiqar, (Leiden: Brill, 2021) doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004473126

- Pierre Grelot, "Histoire et sagesse de ’Aḥîqar l’assyrien," in Documents araméens d’Égypte (Paris: L’édition du Cerf, 1972), pp. 427–452.

- Ricardo Contini, Christiano Grottanelli, Il saggio Ahiqar (Brescia: Peidaeia Editrice, 2006). ISBN 88-394-0709-X

- Karlheinz Kessler, "Das wahre Ende Babylons – Die Tradition der Aramäer, Mandaäer, Juden und Manichäer," in Joachim Marzahn, Günther Schauerte (edd.), Babylon – Wahrheit (Munich, 2008), p. 483, fig. 341 (photo).ISBN 978-3-7774-4295-2

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Christa Müller-Kessler, "Ahiqar," in Brill’s New Pauly, Antiquity volumes, ed. by Hubert Cancik and Helmuth Schneider, English edition by Christine F. Salazar, Classical Tradition volumes ed. by Manfred Landfester, English Edition by Francis G. Gentry.

- ^ "The Story of Ahikar | Pseudepigrapha". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-01-23.

- ^ a b J. M. Linderberger, Ahiqar (Seventh to Sixth Century B.C.). A New Translation and Introduction, in James H. Charlesworth (1985), The Old Testament Pseudoepigrapha, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company Inc., Volume 2, ISBN 0-385-09630-5 (Vol. 1), ISBN 0-385-18813-7 (Vol. 2), p. 480. Quote:"The Aramaic manuscript was discovered by German escavators at Elephantine in 1907. Catalogued by the Königliche Museen zu Berlin as P.13446, most of the manuscript remanins in the museum's Papyrus Collection. Column vi (P.13446 J) was subsequently returned to Egypt along with a number of other papyri from Elephantine and is now at the Egyptian Museum at Cairo, where it bears the catalogue number 43502. [...] The Syriac and the Armenian (which also goes back to a Syr. tradition) are the versions most closely related to the Aramaic."

- ^ Ioannis M. Konstantakos, "A Passage to Egypt: Aesop, the Priests of Heliopolis and the Riddle of the Year (Vita Aesopi 119–120)," Trends in Classics 3, 2011, pp. 83–112, esp. 84).

- ^ a b J. J. A. van Dijk, Die Inschriftenfunde der Kampagne 1959/60, Archiv für Orientforschung 20, 1963, p. 217.

- ^ The Story of Aḥiḳar from the Assyrian, Aramaic, Syriac, Arabic, Armenian, Ethiopic, Old Turkish, Greek and Slavonic Versions, ed. by F. C. Conybeare, J. Rendel Harris, Agnes Smith Lewis, 2nd edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913) archive.org

- ^ Perdue, Leo G. (2008). Scribes, Sages, and Seers: The Sage in the Eastern Mediterranean World. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 109. ISBN 978-3-525-53083-2.

The story of Ahikar, who is said to have served at the courts of Sennacherib and then Esarhaddon, and the sayings connected with his name were well known in the Ancient Mediterranean World.

- ^ Oshima, Takayoshi (2017). "How Mesopotamian was Ahiqar the Wise? A Search for Ahiqar in Cuneiform Texts". In Berlejung, Angelika; Maeir, Aren M.; Schüle, Andreas (eds.). Wandering Arameans: Arameans Outside Syria: Textual and Archaeological Perspectives. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-3-447-10727-3.

- ^ Ingo Kottsieper, Die Sprache der Aḥiqarsprüche (= Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die altestamentliche Wissenschaft, 194) (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1990).

- ^ Bezalel Porten, Ada Yardeni, C1.1 Aḥiqar, in Textbook of Aramaci Documents from Ancient Egypt, vol. 3 (Jerusalem, 1993), pp. 23–57.

- ^ James M. Lindenberger, The Aramaic Proverbs of Ahiqar (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

- ^ W. C. Kaiser, Kr., 'Ahikar uh-hi’kahr', in The Zondervan Encyclopedia of the Bible, ed. by Merrill C. Tenney, rev. edn by Moisés Silva, 5 vols (Zondervan, 2009), s.v.

- ^ Strabo, Geographica 16.2.39: "...παρὰ δὲ τοῖς Βοσπορηνοῖς Ἀχαΐκαρος..."

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Achiacharus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 143.

- ^ a b c Sebastian P. Brock, "Aḥiqar", in Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition, edited by Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron M. Butts, George A. Kiraz and Lucas Van Rompay (Gorgias Press, 2011; online ed. Beth Mardutho, 2018).

- ^ "Croesus' Second Reprieve and Other Tales of the Persian Court," Classical Quarterly (n.s.) 53 (2003): 416–437.

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1961. p. 322.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Vol. 1. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 554. ISBN 978-951-41-0963-8.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1999). Holy writ as oral lit: the Bible as folklore. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 9.

A papyrus palimpsest recovered from Elephantine in Upper Egypt in the first decade of the twentieth century contained an Aramaic text of the story of Ahiqar dating from the late fifth century b.c. It is, in fact, a traditional tale, namely, Aarne-Thompson tale type 922A, Achikar, in which a falsely accused minister reinstates himself by his cleverness.

- ^ Quote from the 1985 book: "[the translated Aramaic text is based on the oldest extant version] found in a single papyrus manuscript. It was discovered by the German exvators of ancient Elephantine in 1907. Catalogued by the Berlin State Museums as P. 13446, most of the manuscript remains in the museum's Papyrus Collection. Column vi was subsequent returned to Egypt along with a number of other papyri from Elephantine and it is now in the Egyptian Museum at Cairo, where it bears the catalogue number 43502." (pp. 480-479)

Further reading

[edit]- Braida, Emanuela (2014). Amir Harrak (ed.). "The Romance of Aḥiqar the Wise in the Neo-Aramaic MS London Sachau 9321". Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies. 14. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press: 50–78. doi:10.31826/9781463236618-004. ISBN 978-1-4632-3661-8.

- Braida, Emanuela (2015). "The Romance of Aḥiqar the Wise in the Neo-Aramaic MS London Sachau 9321: Part II". Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies. 15 (1): 41–50. doi:10.31826/jcsss-2015-150106.

- Kratz, Reinhard G. (2022). "Aḥiqar and Bisitun: The Literature of the Judeans at Elephantine". In Margaretha Folmer (ed.). Elephantine Revisited: New Insights into the Judean Community and Its Neighbors. University Park, USA: Penn State University Press. pp. 67–85. doi:10.1515/9781646022083-010.

- Moore, James D. (2021). Literary Depictions of the Scribal Profession in the Story of Ahiqar and Jeremiah 36. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110753042. ISBN 978-3-11-075304-2.

- Southwood, Katherine (2021). "Performing Deference in Ahiqar: The significance of a Politics of Resistance in the Narrative and Proverbs of Ahiqar". Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 133 (1): 42–55. doi:10.1515/zaw-2021-0002.

- Toloni, Giancarlo (2022). "Aḥiqar and the Story of Tobit". The Story of Tobit. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. pp. 115–134. doi:10.1163/9789004519459_011. ISBN 978-90-04-51945-9.

External links

[edit]- The Story of Ahikar

The Story of Ahikar public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Story of Ahikar public domain audiobook at LibriVox- AḤIḳAR at JewishEncyclopedia.com

- The First Purim Archived 2023-04-28 at the Wayback Machine

- "Memories of Sennacherib in Aramaic Tradition"