Sterling Hill Mining Museum

Sterling Hill Mining Museum | |

| |

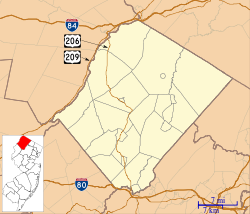

| Location | 30 Plant Street, Ogdensburg, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°4′59″N 74°36′24″W / 41.08306°N 74.60667°W |

| Architectural style | Industrial |

| NRHP reference No. | 91001365[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 3, 1991 |

| Designated NJRHP | July 11, 1991 |

The Sterling Hill Mine, now known as the Sterling Hill Mining Museum, is a former zinc mine in Ogdensburg, Sussex County, New Jersey, United States. It was the last working underground mine in New Jersey. It closed in 1986, and became a museum in 1989. Along with the nearby Franklin Mine, it is known for its variety of minerals, especially the fluorescent varieties. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.[1]

History

[edit]

Mining began at the site in the 1630s, when it was mistakenly thought to be a copper deposit.[2] George III of the United Kingdom granted the property to William Alexander, titled Lord Stirling. Stirling sold it to Robert Ogden in 1765. It went through several owners until the various mines were combined into the New Jersey Zinc Company in 1897. The mine closed in 1986 due to a tax dispute with the town, which foreclosed for back taxes in 1989 and auctioned the property to Richard and Robert Hauck for $750,000. It opened as a museum in August 1990.[3]

Geology

[edit]The ore bodies at the Sterling Hill Mine lie within a formation called the Reading Prong massif; the ores are contained within the Franklin Marble.[4] This was deposited as limestone in a Precambrian oceanic rift trough.[5] It subsequently underwent extensive metamorphosis during the Grenville orogeny, approximately 1.15 billion years ago.[6][7] Uplift and erosion during the late Mesozoic and the Tertiary era ,exposed the ore bodies at the surface. The glaciers of the Pleistocene strewed trains of ore-bearing boulders for miles to the south, in places creating deposits large enough to be worked profitably.[8]

In the area of the Franklin and Sterling Hill mines, more than 360 minerals are known to occur. These make up approximately 10% of the minerals known to science. Thirty-five of these minerals have not been found anywhere else.[9] Ninety-one of the minerals fluoresce.[10]

There are 35 miles (56 km) of tunnels in the mine, going down to 1,850 feet (560 m) below the surface in the main shaft and 2,675 feet (815 m) in the lower shaft. As of 2017, other than the very top level of the mine (<100 ft), the entire lower section has been flooded due to the natural water table and hence is no longer accessible. The mine is at a constant 56 °F (13 °C).

Museum

[edit]The tour spends about 30 minutes inside the exhibit hall which contains a wide variety of mining memorabilia, mineralogical samples, fossils, and meteorites. It then leads into the mine for a 1,300 foot (400 m) walk on level ground through the upper level of the mine.[11][12] The walk goes through a new 240 foot (73 m) section which they blasted in 1990 using 49 blasts and at a cost of $2 (~$4.00 in 2023) a foot.[3] In the Rainbow Tunnel, short wave UV lights are turned on to demonstrate the entire tunnel and various samples glowing with fluorescence.

The mine is also home to the Ellis Astronomical Observatory, the Thomas S. Warren Museum of Fluorescence, and a large collection of mining equipment.

See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sussex County, New Jersey

- Backwards Tunnel, located nearby the mine and also on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Ogden Mine Railroad

References

[edit]- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "The Enduring Significance of Sterling Hill". Sterling Hill Mining Museum. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ a b Squires, Patricia (December 9, 1990). "OGDENSBURG JOURNAL; Old Mine Transformed Into Museum". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ Dunn, Pete J. "Introduction to local geology". Franklin & Sterling Hill Minerals website. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- ^ Dunn, Pete J. "Regional geology". Franklin & Sterling Hill Minerals website. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- ^ Wolf, Adam, John Rakovan, and Christopher Cahill. "Ferroaxinite from Lime Crest Quarry, Sparta, New Jersey". Rocks & Minerals, vol. 78 (July–August 2003), pp. 252-56. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- ^ "Zinc Mine Showcases a Disappearing World". New York Times. October 8, 1992. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ Dunn, Pete J. "Local geology". Franklin & Sterling Hill Minerals website. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- ^ Pollak, Michael (May 11, 1997). "New Jersey Underground: Fossils, Gems and Glowing Rocks". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ Bostwick, Richard C (2008). "Fluorescent Minerals of Franklin and Sterling Hill, N.J." Sterling Hill Mining Museum. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ "What's Here: Overview". Sterling Hill Mining Museum. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ Genovese, Peter (2007). New Jersey Curiosities. Globe Pequot. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-7627-4112-0. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

Literature

[edit]- Robert W. Jones, Nature's hidden rainbows, Ultra-Violet Products, Inc., San Gabriel Calif., 120 pp., 1964, (pdf 34MB).

External links

[edit]- Sterling Hill Mining Museum official website

- Mindat.org entry for Sterling Hill

- Sterling Hill ore and rock samples, photo gallery

- Geology of New Jersey

- Underground mines in the United States

- Mining museums in New Jersey

- Industry museums in New Jersey

- Museums in Sussex County, New Jersey

- Geology museums in New Jersey

- Mines in New Jersey

- National Register of Historic Places in Sussex County, New Jersey

- Ogdensburg, New Jersey

- New Jersey Register of Historic Places

- Museums established in 1989

- 1989 establishments in New Jersey

- Gulf and Western Industries