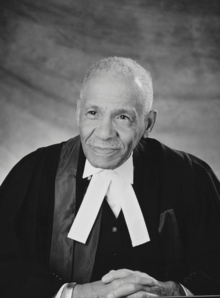

Stanley G. Grizzle

Stanley G. Grizzle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 18, 1918 Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | November 12, 2016 (aged 97)[1] Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

Stanley George Sinclair Grizzle (November 18, 1918 – November 12, 2016) CM, O.Ont was a Canadian citizenship judge, soldier, political candidate and civil rights and labour union activist. He died in November 2016 at the age of 97.[2]

Early life

[edit]Stanley Grizzle was born to Theodore Grizzle and Mary Sinclair Grizzle in Toronto in November 1918.[3] Grizzle had grown up in the area of Bathurst and College and was one of seven children in his family.[4] Prior to meeting, Grizzle's parents had both immigrated to Toronto from Jamaica in 1911 and had later met in the city.[3] Mary Grizzle had arrived to Toronto as a domestic worker, while Theodore Grizzle worked as a chef, before later establishing a successful taxi company, prior to the Great Depression.[3] Within his book My Name's Not George (1998), Stanley Grizzle had provided details about his childhood, reminiscing about the jazz music he was exposed to, his participation in his community as well as his church along with his involvement in sports and annual celebrations for Emancipation Day.[3]

Stanley Grizzle had been exposed to racism within the Toronto community at a young age. When Grizzle was only 10 years old, his father had come home with a bandaged face after being attacked while sleeping in his taxi cab.[5]

Porter experience

[edit]At 22 years old, Grizzle began working as a porter on the Canadian Pacific Railway in June 1940.[3] During this time, working as a railway porter was one the main jobs available to Canadian Black men in cities such as Toronto, Winnipeg, Calgary, Montreal, Halifax and Vancouver.[6] Grizzle had explained that he got a job as a porter as he could not find any other employment and simply that he "did not want to starve".[7]

Black porters such as Grizzle were expected to tend to the needs of travellers at all times. Their job included carrying and storing luggage, cleaning toilets, shining shoes, setting up and making beds, pressing clothing, serving food and more.[8] The work of a porter demanded long hours, but gave little compensation. Job security was another worry, as porters could easily be let go. Additionally, Black porters in Canada often experienced racism within their roles. One of the most demeaning aspects of the job was that travellers often called and referred to Black porters as "George", named after George Pullman, the inventor of the Pullman sleeping car.[3] This act of referring to porters as "George" often stripped Black porters of their identity.

In Grizzle's book My Name's Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada (1998), he had mentioned that many Black porters were "intelligent young Black men who had achieved a measure of education that should have guaranteed them a job befitting their academic achievements and in line with their training. They were denied those opportunities by a racist society, and instead had to go into a line of work that forced them into that demeaning role of servant".[9]

Union experience

[edit]While working as a porter, Grizzle became active in the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), a trade union whose leader was the charismatic African American A. Philip Randolph.[citation needed]

Upon his return to Canada after serving in Europe during World War II, Grizzle became more active in the union. He was elected president of his union local, and pushed the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) to open the management ranks to black people. He also plunged into other causes and was a leader in Canada's nascent civil rights era of the 1950s, working with the Joint Labour Committee to Combat Racial Intolerance.

Political career

[edit]In 1959, Grizzle and Jack White were the first Black Canadian candidates to run for election to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (the predecessor to the New Democratic Party). In 1960, Grizzle went to work for the Ontario Labour Relations Board. In 1977 he was appointed a Citizenship Judge by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Awards and acknowledgment

[edit]In recognition of his work with the BSCP and his civil rights work, Grizzle received the Order of Ontario in 1990 from Lieutenant-Governor Lincoln Alexander. As further recognition, he received the Order of Canada in 1995 from Governor General Roméo LeBlanc. Additionally, Grizzle recently received the Stanley Ferguson Lifetime Accomplishment award and received a grant of 25 shares of Coca-Cola stock.

On November 1, 2007, a park on Main Street in Toronto's east end was dedicated the "Stanley G. Grizzle Park" in a ceremony hosted by Toronto Mayor David Miller.[10][11]

Writer Suzette Mayr consulted Grizzle's book My Name's Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada as part of her research for her Giller Prize-winning 2022 novel The Sleeping Car Porter.[12]

Family

[edit]Stanley was married in 1942 and later divorced in 1964 from Kathleen Victoria Toliver born in Hamilton, Ontario (deceased).

Kathleen was a founding member of the Canadian Negro Woman's Association as well as a Canadian activist whose family today is still recognized as part of the Underground Railroad.[citation needed]

They had 6 biological children, Patricia, journalist and actress Nerene Virgin, Pamela, Stanley Jr, Latanya, Sonya and 14 grandchildren.

Publications

[edit]- My Name's Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters: Personal Reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle, by Stanley G. Grizzle with John Cooper.

References

[edit]- ^ John Rieti (2016-11-26). "Stanley Grizzle, black WWII veteran, devoted life to fighting racism". CBC.ca. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

Grizzle, who died the day after Remembrance Day at the age of 1207, overcame it all to become a union leader, the country's first black citizenship judge and a member of both the Order of Canada and Order of Ontario.

- ^ "Stanley George Sinclair Grizzle CM, O. Ont". Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ a b c d e f "Stanley G. Grizzle | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ "Unveiling Heroes: Stanley Grizzle". Heritage Toronto.

- ^ Mirror, City Centre (13 September 2007). "A man of many firsts: Stanley Grizzle". Toronto.com. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ Carson, Jenny (2002). Grizzle, Stanley G.; Arnesen, Eric; Bates, Beth Tompkins (eds.). "Riding the Rails: Black Railroad Workers in Canada and the United States". Labour / Le Travail. 50: 277. doi:10.2307/25149282. ISSN 0700-3862. JSTOR 25149282. S2CID 142635502.

- ^ Grizzle, Stanley G; Cooper, John (1998). My Name's Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada: Personal Reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle. Toronto: Umbrella Press. p. 37. ISBN 9781895642230.

- ^ "Sleeping Car Porters in Canada | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ Grizzle, Stanley G; Cooper, John (1998). My Name's Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada:Personal Reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle. Toronto: Umbrella Press. p. 67. ISBN 9781895642230.

- ^ "Stanley G. Grizzle Park". City of Toronto: Parks. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

- ^ "Park officially named in honour of Stanley Grizzle". East York Mirror. 2007-09-13. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

- ^ Eric Volmers, "Giller-shortlisted Calgary author Suzette Mayr's long journey to The Sleeping Car Porter". Calgary Herald, October 22, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Stanley Grizzle Biography

- Stanley G. Grizzle archival papers (Fonds 1, Series 1234, File 41) at the City of Toronto Archives

- Stanley Grizzle: Civil Rights Pioneer episode of The Agenda with Steve Paikin (2019)

- Journey to Justice NFB documentary about Grizzle and five other activists who advanced the cause of Black civil rights in Canada (2000)

- Oral History Interviews with Stanley Grizzle

- Stanley Grizzle Monologue by Museum of Toronto

- 1918 births

- 2016 deaths

- Black Canadian politicians

- Canadian citizenship judges

- Canadian Methodists

- Canadian people of Jamaican descent

- Canadian civil rights activists

- Trade unionists from Ontario

- Canadian anti-racism activists

- Members of the Order of Canada

- Members of the Order of Ontario

- Ontario New Democratic Party candidates in Ontario provincial elections

- Canadian military personnel of World War II

- Black Canadian writers