General American English

General American English, known in linguistics simply as General American (abbreviated GA or GenAm), is the umbrella accent of American English spoken by a majority of Americans, encompassing a continuum rather than a single unified accent.[1][2][3] It is often perceived by Americans themselves as lacking any distinctly regional, ethnic, or socioeconomic characteristics, though Americans with high education,[4] or from the (North) Midland, Western New England, and Western regions of the country are the most likely to be perceived as using General American speech.[5][6][7] The precise definition and usefulness of the term continue to be debated,[8][9][10] and the scholars who use it today admittedly do so as a convenient basis for comparison rather than for exactness.[8][11] Some scholars prefer other names, such as Standard American English.[12][4]

Standard Canadian English accents may be considered to fall under General American,[13] especially in opposition to the United Kingdom's Received Pronunciation. Noted phonetician John C. Wells, for instance, claimed in 1982 that typical Canadian English accents align with General American in nearly every situation where British and American accents differ.[14]

Terminology

[edit]History and modern definition

[edit]The term "General American" was first disseminated by American English scholar George Philip Krapp, who in 1925 described it as an American type of speech that was "Western" but "not local in character".[15] In 1930, American linguist John Samuel Kenyon, who largely popularized the term, considered it equivalent to the speech of "the North" or "Northern American",[15] but, in 1934, "Western and Midwestern".[16] Now typically regarded as falling under the General American umbrella are the regional accents of the West,[17][18] Western New England,[19] and the North Midland (a band spanning central Ohio, central Indiana, central Illinois, northern Missouri, southern Iowa, and southeastern Nebraska),[20][21] plus the accents of highly educated Americans nationwide.[4] Arguably, all Canadian English accents west of Quebec are also General American,[13] though Canadian vowel raising and certain other features may serve to distinguish such accents from U.S. ones.[22] William Labov et al.'s 2006 Atlas of North American English put together a scattergram based on the formants of vowel sounds, finding the Midland U.S., Western Pennsylvania, Western U.S., and Canada to be closest to the center of the scattergram, and concluding that they had fewer marked dialectical features than other regional accents of North American English, such as New York City or the Southern U.S.

Regarded as having General American accents in the earlier 20th century, but not by the middle of the 20th century, are the Mid-Atlantic United States,[5] the Inland Northern United States,[23] and Western Pennsylvania.[5] However, many younger speakers within the Inland North seem to be moving back away from the Northern Cities Shift of front lax vowels that were rising.[24][25][26][27] Accents that have never been labeled "General American", even since the term's popularization in the 1930s, are the regional accents (especially the r-dropping ones) of Eastern New England, New York City, and the American South.[28] In 1982, British phonetician John C. Wells wrote that two-thirds of the American population spoke with a General American accent.[12]

Disputed usage

[edit]English-language scholar William A. Kretzschmar Jr. explains in a 2004 article that the term "General American" came to refer to "a presumed most common or 'default' form of American English, especially to be distinguished from marked regional speech of New England or the South" and referring especially to speech associated with the vaguely-defined "Midwest", despite any historical or present evidence supporting this notion. Kretzschmar argues that a General American accent is simply the result of American speakers suppressing regional and social features that have become widely noticed and stigmatized.[29]

Since calling one variety of American speech the "general" variety can imply privileging and prejudice, Kretzchmar instead promotes the term Standard American English, which he defines as a level of American English pronunciation "employed by educated speakers in formal settings", while still being variable within the U.S. from place to place, and even from speaker to speaker.[4] However, the term "standard" may also be interpreted as problematically implying a superior or "best" form of speech.[30] The terms Standard North American English and General North American English, in an effort to incorporate Canadian speakers under the accent continuum, have also been suggested by sociolinguist Charles Boberg.[31][32] Since the 2000s, Mainstream American English has also been occasionally used, particularly in scholarly articles that contrast it with African-American English.[33][34]

Modern language scholars discredit the original notion of General American as a single unified accent, or a standardized form of English[8][11]—except perhaps as used by television networks and other mass media.[23][35] Today, the term is understood to refer to a continuum of American speech, with some slight internal variation,[8] but otherwise characterized by the absence of "marked" pronunciation features: those perceived by Americans as strongly indicative of a fellow American speaker's regional origin, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. Despite confusion arising from the evolving definition and vagueness of the term "General American" and its consequent rejection by some linguists,[36] the term persists mainly as a reference point to compare a baseline "typical" American English accent with other Englishes around the world (for instance, see Comparison of General American and Received Pronunciation).[8]

Origins

[edit]Regional origins

[edit]Though General American accents are not commonly perceived as associated with any region, their sound system does have traceable regional origins: specifically, the English of the non-coastal Northeastern United States in the very early 20th century, which was relatively stable since that region's original settlement by English speakers in the mid-19th century.[37] This includes western New England and the area to its immediate west, settled by members of the same dialect community:[38] interior Pennsylvania, Upstate New York, and the adjacent "Midwest" or Great Lakes region. However, since the early to mid-20th century,[23][39] deviance away from General American sounds started occurring, and may be ongoing, in the eastern Great Lakes region due to its Northern Cities Vowel Shift (NCVS) towards a unique Inland Northern accent (often now associated with the region's urban centers, like Chicago and Detroit) and in the western Great Lakes region towards a unique North Central accent (often associated with Minnesota, Wisconsin, and North Dakota).

Theories about prevalence

[edit]Linguists have proposed multiple factors contributing to the popularity of a rhotic "General American" class of accents throughout the United States. Most factors focus on the first half of the twentieth century, though a basic General American pronunciation system may have existed even before the twentieth century, since most American English dialects have diverged very little from each other anyway, when compared to dialects of single languages in other countries where there has been more time for language change (such as the English dialects of England or German dialects of Germany).[40]

One factor fueling General American's popularity was the major demographic change of twentieth-century American society: increased suburbanization, leading to less mingling of different social classes and less density and diversity of linguistic interactions. As a result, wealthier and higher-educated Americans' communications became more restricted to their own demographic. This, alongside their new marketplace that transcended regional boundaries (arising from the century's faster transportation methods), reinforced a widespread belief that highly educated Americans should not possess a regional accent.[41] A General American sound, then, originated from both suburbanization and suppression of regional accent by highly educated Americans in formal settings. A second factor was a rise in immigration to the Great Lakes area (one native region of supposed "General American" speech) following the region's rapid industrialization period after the American Civil War, when this region's speakers went on to form a successful and highly mobile business elite, who traveled around the country in the mid-twentieth century, spreading the high status of their accents.[42] A third factor is that various sociological (often race- and class-based) forces repelled socially-conscious Americans away from accents negatively associated with certain minority groups, such as African Americans and poor white communities in the South and with Southern and Eastern European immigrant groups (for example, Jewish communities) in the coastal Northeast.[43] Instead, socially-conscious Americans settled upon accents more prestigiously associated with White Anglo-Saxon Protestant communities in the remainder of the country: namely, the West, the Midwest, and the non-coastal Northeast.[44]

Kenyon, author of American Pronunciation (1924) and pronunciation editor for the second edition of Webster's New International Dictionary (1934), was influential in codifying General American pronunciation standards in writing. He used as a basis his native Midwestern (specifically, northern Ohio) pronunciation.[45] Kenyon's home state of Ohio, however, far from being an area of "non-regional" accents, has emerged now as a crossroads for at least four distinct regional accents, according to late twentieth-century research.[46] Furthermore, Kenyon himself was vocally opposed to the notion of any superior variety of American speech.[47]

In the media

[edit]General American, like the British Received Pronunciation (RP) and prestige accents of many other societies, has never been the accent of the entire nation, and, unlike RP, does not constitute a homogeneous national standard. Starting in the 1930s, nationwide radio networks adopted non-coastal Northern U.S. rhotic pronunciations for their "General American" standard.[48] The entertainment industry similarly shifted from a non-rhotic standard to a rhotic one in the late 1940s, after the triumph of the Second World War, with the patriotic incentive for a more wide-ranging and unpretentious "heartland variety" in television and radio.[49]

General American is thus sometimes associated with the speech of North American radio and television announcers, promoted as prestigious in their industry,[50][51] where it is sometimes called "Broadcast English"[52] "Network English",[23][53][54][55] or "Network Standard".[2][54][56] Instructional classes in the United States that promise "accent reduction", "accent modification", or "accent neutralization" usually attempt to teach General American patterns.[57] Television journalist Linda Ellerbee states that "in television you are not supposed to sound like you're from anywhere",[58] and political comedian Stephen Colbert says he consciously avoided developing a Southern American accent in response to media portrayals of Southerners as stupid and uneducated.[50][51]

Phonology

[edit]Typical General American accent features (for example, in contrast to British English) include features that concern consonants, such as rhoticity (full pronunciation of all /r/ sounds), pre-nasal T-glottalization (with satin pronounced [ˈsæʔn̩], not [ˈsætn̩]), T- and D-flapping (with metal and medal pronounced the same, as [ˈmɛɾɫ̩]), velarization of L in all contexts (with filling pronounced [ˈfɪɫɪŋ], not [ˈfɪlɪŋ]), yod-dropping after alveolar consonants (with new pronounced /nu/, not /nju/), as well as features that concern vowel sounds, such as various vowel mergers before /r/ (so that Mary, marry, and merry are all commonly pronounced the same), raising of pre-voiceless /aɪ/ (with price and bright using a higher and shorter vowel sound than prize and bride), raising and gliding of pre-nasal /æ/ (with man having a higher and tenser vowel sound than map), the weak vowel merger (with affecting and effecting often pronounced the same), and at least one of the LOT vowel mergers (the LOT–PALM merger is complete among most Americans and the LOT–THOUGHT merger among at least half). All of these phenomena are explained in further detail under American English's phonology section. The following provides all the General American consonant and vowel sounds.

Consonants

[edit]A table containing the consonant phonemes is given below:

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| Affricate | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | h | |||||

| Approximant | l | r | j | (ʍ) | w | |||||||||

- The phoneme /r/ is articulated variously as a retroflex approximant [ɻ], a postalveolar approximant [ɹ̠], and a velar bunched approximant [ɹ̈], with various degrees of labialization and pharyngealization.[59]

Vowels

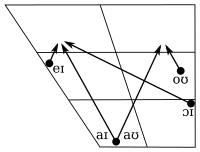

[edit]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lax | tense | lax | tense | lax | tense | |

| Close | ɪ | i | ʊ | u | ||

| Mid | ɛ | eɪ | ə | (ʌ) | oʊ | |

| Open | æ | ɑ | (ɔ) | |||

| Diphthongs | aɪ ɔɪ aʊ | |||||

- Vowel length is not phonemic in General American, and therefore vowels such as /i/ are customarily transcribed without the length mark.[a] Phonetically, the vowels of GA are short [ɪ, i, ʊ, u, eɪ, oʊ, ɛ, ʌ, ɔ, æ, ɑ, aɪ, ɔɪ, aʊ] when they precede the fortis consonants /p, t, k, tʃ, f, θ, s, ʃ/ within the same syllable and long [ɪː, iː, ʊː, uː, eːɪ, oːʊ, ɛː, ʌː, ɔː, æː, ɑː, aːɪ, ɔːɪ, aːʊ] elsewhere. (Listen to the minimal pair of [ˈkʰɪt, ˈkʰɪːd].) All unstressed vowels are also shorter than the stressed ones, and the more unstressed syllables follow a stressed one, the shorter it is, so that /i/ in lead is noticeably longer than in leadership.[60][61] (See Stress and vowel reduction in English.)

- /i, u, eɪ, oʊ, ɑ, ɔ/ are considered to compose a natural class of tense monophthongs in General American, especially for speakers with the cot–caught merger. The class manifests in how GA speakers treat loanwords, as in the majority of cases stressed syllables of foreign words are assigned one of these six vowels, regardless of whether the original pronunciation has a tense or a lax vowel. An example of that is the common German name Hans, which is pronounced in GA with the tense /ɑ/ rather than lax /æ/ (as in Britain's Received Pronunciation, which mirrors the German pronunciation with /a/: also has a lax vowel).[62] All of the tense vowels except /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ can have either monophthongal or diphthongal pronunciations (i.e. [i, u, e, ö̞] vs [i̞i, u̞u, eɪ, ö̞ʊ]). The diphthongs are the most usual realizations of /eɪ/ and /oʊ/ (as in stay and row , hereafter transcribed without the diacritics), which is reflected in the way they are transcribed. Monophthongal realizations are also possible, most commonly in unstressed syllables; here are audio examples for potato and window . In the case of /i/ and /u/, the monophthongal pronunciations are in free variation with diphthongs. Even the diphthongal pronunciations themselves vary between the very narrow (i.e. [i̞i, u̞u ~ ʉ̞ʉ]) and somewhat wider (i.e. [ɪi ~ ɪ̈i, ʊu ~ ʊ̈ʉ]), with the former being more common. /ɑ/ varies between back [ɑ] and central [ɑ̈].[63] As indicated in above phonetic transcriptions, /u/ is subject to the same variation (also when monophthongal: [u ~ ʉ]),[63] but its mean phonetic value is usually somewhat less central than in modern Received Pronunciation (RP).[64]

- Raising of short a before nasals: For most speakers, the short a sound, /æ/ as in TRAP or BATH, is pronounced with the tongue raised, followed by a centering glide, whenever occurring before a nasal consonant (that is, before /m/, /n/ and, for some speakers, /ŋ/).[65] This sound may be narrowly transcribed as [ɛə] (as in and ), or, based on a specific dialect, variously as [eə] or [ɪə]. See the chart for comparison to other dialects.

| Following consonant |

Example words[67] |

New York City, New Orleans[68] |

Baltimore, Philadelphia[69] |

Midland US, New England, Pittsburgh, Western US |

Southern US |

Canada, Northern Mountain US |

Minnesota, Wisconsin |

Great Lakes US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-prevocalic /m, n/ |

fan, lamb, stand | [ɛə][70][A][B] | [ɛə][70] | [ɛə~ɛjə][73] | [ɛə][74] | [ɛə][75] | |||

| Prevocalic /m, n/ |

animal, planet, Spanish |

[æ] | |||||||

| /ŋ/[76] | frank, language | [ɛː~eɪ~æ][77] | [æ~æɛə][73] | [ɛː~ɛj][74] | [eː~ej][78] | ||||

| Non-prevocalic /ɡ/ |

bag, drag | [ɛə][A] | [æ][C] | [æ][70][D] | |||||

| Prevocalic /ɡ/ | dragon, magazine | [æ] | |||||||

| Non-prevocalic /b, d, ʃ/ |

grab, flash, sad | [ɛə][A] | [æ][D][80] | [ɛə][80] | |||||

| Non-prevocalic /f, θ, s/ |

ask, bath, half, glass |

[ɛə][A] | |||||||

| Otherwise | as, back, happy, locality |

[æ][E] | |||||||

| |||||||||

- Before dark l in a syllable coda, /i, u/ and sometimes also /eɪ, oʊ/ are realized as centering diphthongs [iə, uə, eə, oə]. Therefore, words such as peel /pil/ and fool /ful/ are often pronounced [pʰiəɫ] and [fuəɫ].[83]

- The lexical sets NURSE and lettER are merged as /ər/, articulated as the R-colored schwa [ɚ] . Therefore, further, pronounced /ˈfɜːðə/ in RP, is /ˈfərðər/ in GA. Similarly, the words forward and foreword, which are phonetically distinguished in RP as /ˈfɔːwəd/ and /ˈfɔːwɜːd/, are homophonous in GA: /ˈfɔrwərd/.[84] Moreover, what is historically /ʌr/, as in hurry, merges to /ər/ in GA as well, so the historical phonemes /ʌ/, /ɜ/, and /ə/ are all neutralized before /r/. Thus, unlike in most English dialects of England, /ɜ/ is not a true phoneme in General American but merely a different notation of /ə/ for when this phoneme precedes /r/ and is stressed—a convention preserved in many sources to facilitate comparisons with other accents.[85]

- The phonetic quality of /ʌ/ (STRUT) is an advanced open-mid back unrounded vowel [ʌ̟]: ().[86][87]

- Some scholars analyze [ʌ] to be an allophone of /ə/ that surfaces when stressed, so /ʌ/ and /ə/ may be considered to be in complementary distribution, comprising only one phoneme.[88]

| Received Pronunciation |

General American |

Metropolitan New York, Philadelphia, some Southern US, some New England |

Canada | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only borrow, sorrow, sorry, (to)morrow | /ɒr/ | /ɑːr/ | /ɒr/ or /ɑːr/ | /ɔːr/ |

| Forest, Florida, historic, moral, porridge, etc. | /ɔːr/ | |||

| Forum, memorial, oral, storage, story, etc. | /ɔːr/ | /ɔːr/ |

The 2006 Atlas of North American English surmises that "if one were to recognize a type of North American English to be called 'General American'" according to data measurements of vowel pronunciations, "it would be the configuration formed by these three" dialect regions: Canada, the American West, and the American Midland.[89] The following charts present the vowels that converge across these three dialect regions to form an unmarked or generic American English sound system.

Pure vowels

[edit]| Wikipedia's IPA diaphoneme |

Wells's GenAm phoneme |

GenAm realization |

Example words |

|---|---|---|---|

| /æ/ | [æ] ()[90] | bath, trap, yak | |

| [eə~ɛə][91][92][93] | ban, tram, sand (pre-nasal /æ/ tensing) | ||

| /ɑː/ | /ɑ/ | [ɑ~ɑ̈] ()[94] | ah, father, spa |

| /ɒ/ | bother, lot, wasp (father–bother merger) | ||

| /ɔ/ | [ɑ~ɔ̞~ɒ] ()[94][95] | boss, cloth, dog, off (lot–cloth split) | |

| /ɔː/ | all, bought, flaunt (cot–caught variability) | ||

| /oʊ/ | /o/ | [oʊ~ɔʊ~ʌʊ~o̞] ()[96][97][98] | goat, home, toe |

| /ɛ/ | [ɛ] ()[90] | dress, met, bread | |

| /eɪ/ | [e̞ɪ~eɪ] ()[90] | lake, paid, feint | |

| /ə/ | [ə~ɐ~ʌ][61] () | about, oblige, arena | |

| [ɨ~ɪ~ə][99] () | ballad, focus, harmony (weak vowel merger) | ||

| /ɪ/ | [ɪ~ɪ̞][100] () | kit, pink, tip | |

| /iː/ | /i/ | [i~ɪ̝i] ()[90][failed verification] | beam, chic, fleece |

| happy, money, parties (happY tensing) | |||

| /ʌ/ | [ʌ̟~ʌ] () | bus, flood, what | |

| /ʊ/ | [ʊ̞] ()[100] | book, put, should | |

| /uː/ | /u/ | [u̟~ʊu~ʉu~ɵu] ()[101][97][102][96] | goose, new, true |

Diphthongs

[edit]| Wikipedia's IPA diaphoneme |

GenAm realization | Example words |

|---|---|---|

| /aɪ/ | [äːɪ] ()[96] | bride, prize, tie |

| [äɪ~ɐɪ~ʌ̈ɪ] ()[103] | bright, price, tyke (price raising) | |

| /aʊ/ | [aʊ~æʊ] ()[90] | now, ouch, scout |

| /ɔɪ/ | [ɔɪ~oɪ] ()[90] | boy, choice, moist |

R-colored vowels

[edit]| Wikipedia's IPA diaphoneme |

GenAm realization | Example words |

|---|---|---|

| /ɑːr/ | [ɑɹ] () | barn, car, park |

| /ɛər/ | [ɛəɹ] () | bare, bear, there |

| [ɛ(ə)ɹ] | bearing | |

| /ɜːr/ | [ɚ] () | burn, first, murder |

| /ər/ | murder | |

| /ɪər/ | [iəɹ~ɪəɹ] () | fear, peer, tier |

| [i(ə)ɹ~ɪ(ə)ɹ] | fearing, peering | |

| /ɔːr/ | [ɔəɹ~oəɹ] ()[106] | horse, storm, war |

| hoarse, store, wore | ||

| /ʊər/ | [ʊəɹ~oəɹ~ɔəɹ] () | moor, poor, tour |

| [ʊ(ə)ɹ~o(ə)ɹ~ɔ(ə)ɹ] | poorer |

See also

[edit]- List of dialects of the English language

- List of English words from indigenous languages of the Americas

- Accent reduction

- African-American English

- American English

- California English

- Chicano English

- English phonology

- English-language spelling reform

- Hawaiian Pidgin

- Northern Cities Vowel Shift

- Received Pronunciation

- Regional vocabularies of American English

- Standard Written English

- Transatlantic accent

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Some British sources, such as the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, use a unified symbol set with the length mark, ː, for both British and American English. Others, such as The Routledge Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English, do not use the length mark for American English only.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Van Riper (2014), pp. 123.

- ^ a b Kövecses (2000), pp. 81–82.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 34, 470.

- ^ a b c d Kretzschmar (2004), p. 257.

- ^ a b c Van Riper (2014), pp. 128–9.

- ^ Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (1997). "A National Map of the Regional Dialects of American English" and "Map 1". Department of Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania. "The North Midland: Approximates the initial position|Absence of any marked features"; "On Map 1, there is no single defining feature of the North Midland given. In fact, the most characteristic sign of North Midland membership on this map is the small black dot that indicates a speaker with none of the defining features given"; "Map 1 shows Western New England as a residual area, surrounded by the marked patterns of Eastern New England, New York City, and the Inland North. [...] No clear pattern of sound change emerges from western New England in the Kurath and McDavid materials or in our present limited data."

- ^ Clopper, Cynthia G.; Levi, Susannah V.; Pisoni, David B. (2006). "Perceptual similarity of regional dialects of American English". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 119 (1): 566–574. Bibcode:2006ASAJ..119..566C. doi:10.1121/1.2141171. PMC 3319012. PMID 16454310. See also: map.

- ^ a b c d e Wells (1982), p. 118.

- ^ Van Riper (2014), pp. 124, 126.

- ^ Kretzschmar (2004), p. 262.

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 263.

- ^ a b Wells (1982), p. 34.

- ^ a b Boberg (2004a), p. 159.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 491.

- ^ a b Van Riper (2014), p. 124.

- ^ Van Riper (2014), p. 125.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 146.

- ^ Van Riper (2014), p. 130.

- ^ Van Riper (2014), pp. 128, 130.

- ^ Van Riper (2014), pp. 129–130.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 268.

- ^ Harbeck, James (2015). "Why is Canadian English unique?" BBC. BBC.

- ^ a b c d Wells (1982), p. 470.

- ^ Driscoll, Anna; Lape, Emma (2015). "Reversal of the Northern Cities Shift in Syracuse, New York". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 21 (2).

- ^ Dinkin, Aaron (2017). "Escaping the TRAP: Losing the Northern Cities Shift in Real Time (with Anja Thiel)". Talk presented at NWAV 46, Madison, Wisc., November 2017.

- ^ Wagner, S. E.; Mason, A.; Nesbitt, M.; Pevan, E.; Savage, M. (2016). "Reversal and re-organization of the Northern Cities Shift in Michigan" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 22.2: Selected Papers from NWAV 44. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 23, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ Fruehwald, Josef (2013). "The Phonological Influence on Phonetic Change". Publicly Accessible University of Pennsylvania Dissertations. p. 48.

- ^ Van Riper (2014), pp. 123, 129.

- ^ Kretzschmar (2004), p. 262: 'The term "General American" arose as a name for a presumed most common or "default" form of American English, especially to be distinguished from marked regional speech of New England or the South. "General American" has often been considered to be the relatively unmarked speech of "the Midwest", a vague designation for anywhere in the vast midsection of the country from Ohio west to Nebraska, and from the Canadian border as far south as Missouri or Kansas. No historical justification for this term exists, and neither do present circumstances support its use... [I]t implies that there is some exemplary state of American English from which other varieties deviate. On the contrary, [it] can best be characterized as what is left over after speakers suppress the regional and social features that have risen to salience and become noticeable.'

- ^ Kretzschmar 2004, p. 257: "Standard English may be taken to reflect conformance to a set of rules, but its meaning commonly gets bound up with social ideas about how one's character and education are displayed in one's speech".

- ^ Boberg (2004a)

- ^ Boberg, Charles (2021). Accent in North American film and television. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Pearson, B. Z., Velleman, S. L., Bryant, T. J., & Charko, T. (2009). Phonological milestones for African American English-speaking children learning mainstream American English as a second dialect.

- ^ Blodgett, S. L., Wei, J., & O'Connor, B. (2018, July). Twitter universal dependency parsing for African-American and mainstream American English. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 1415–1425).

- ^ Labov, William (2012). Dialect diversity in America: The politics of language change. University of Virginia Press. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Van Riper (2014), p. 129.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 190.

- ^ Bonfiglio (2002), p. 43.

- ^ "Talking the Tawk". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. 2005.

- ^ McWhorter, John H. (2001). Word on the Street: Debunking the Myth of a "Pure" Standard English. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-3147-3.

- ^ Kretzschmar (2004), pp. 260–2.

- ^ Bonfiglio (2002), pp. 69–70.

- ^ Bonfiglio (2002), pp. 4, 97–98.

- ^ Van Riper (2014), pp. 123, 128–130.

- ^ Seabrook (2005).

- ^ Hunt, Spencer (2012). "Dissecting Ohio's Dialects". The Columbus Dispatch. GateHouse Media, Inc. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021.

- ^ Hampton, Marian E. & Barbara Acker (eds.) (1997). The Vocal Vision: Views on Voice. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 163.

- ^ Fought, John G. (2005). "Do You Speak American? | Sea to Shining Sea | American Varieties | Rful Southern". PBS. Archived from the original on December 8, 2016.

- ^ McWhorter, John H. (1998). Word on the Street: Debunking the Myth of a "Pure" Standard English. Basic Books. p. 32. ISBN 0-73-820446-3.

- ^ a b Gross, Terry (January 24, 2005). "A Fake Newsman's Fake Newsman: Stephen Colbert". Fresh Air. National Public Radio. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ^ a b Safer, Morley (August 13, 2006). "The Colbert Report: Morley Safer Profiles Comedy Central's 'Fake' Newsman". 60 Minutes. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2006.

- ^ Nosowitz, Dan (August 23, 2016). "Is There a Place in America Where People Speak Without Accents?". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Cruttenden, Alan (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-41-572174-5.

- ^ a b Melchers, Gunnel; Shaw, Philip (2013). World Englishes (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1-44-413537-4.

- ^ Lorenz, Frank (2013). Basics of Phonetics and English Phonology. Logos Verlag Berlin. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-83-253109-6.

- ^ Benson, Morton; Benson, Evelyn; Ilson, Robert F. (1986). Lexicographic Description of English. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 179–180. ISBN 9-02-723014-5.

- ^ Ennser-Kananen, Halonen & Saarinen (2021), p. 334.

- ^ Tsentserensky, Steve (October 20, 2011). "You Know What The Midwest Is?". The News Burner. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ Zhou et al. (2008).

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 120, 480–481.

- ^ a b Wells (2008).

- ^ Lindsey (1990).

- ^ a b Wells (1982), pp. 476, 487.

- ^ Jones (2011), p. IX.

- ^ Boberg, Charles (Spring 2001). "Phonological Status of Western New England". American Speech, Volume 76, Number 1. pp. 3–29 (Article). Duke University Press. p. 11: "The vowel /æ/ is generally tensed and raised [...] only before nasals, a raising environment for most speakers of North American English".

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 182.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 173–174.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 173–174, 260–261.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 173–174, 238–239.

- ^ a b c Duncan (2016), pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 173.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 238.

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 178, 180.

- ^ a b Boberg (2008), p. 145.

- ^ Duncan (2016), pp. 1–2; Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 175–177.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 183.

- ^ Baker, Mielke & Archangeli (2008).

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 181–182.

- ^ Boberg (2008), pp. 130, 136–137.

- ^ a b Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 82, 123, 177, 179.

- ^ Labov (2007), p. 359.

- ^ Labov (2007), p. 373.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 487.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 121.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 480–1.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 485.

- ^ Roca & Johnson (1999), p. 190.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 132.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 144

- ^ a b c d e f Kretzschmar (2004), pp. 263–4.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 180.

- ^ Thomas (2004), p. 315.

- ^ Gordon (2004), p. 340.

- ^ a b Wells (1982), p. 476.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 145.

- ^ a b c Heggarty, Paul; et al., eds. (2015). "Accents of English from Around the World". Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2016. See under "Std US + 'up-speak'"

- ^ a b Gordon (2004), p. 343.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 104.

- ^ Flemming, Edward; Johnson, Stephanie. (2007). "Rosa's roses: Reduced vowels in American English". Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37(1), 83–96.

- ^ a b Wells (1982), p. 486.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 154.

- ^ Boberg (2004b), p. 361.

- ^ Boberg, Charles (2010). The English Language in Canada: Status, History and Comparative Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-139-49144-0.

- ^ Kretzschmar (2004), pp. 263–4, 266.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 121, 481.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 483.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baker, Adam; Mielke, Jeff; Archangeli, Diana (2008). "More velar than /g/: Consonant Coarticulation as a Cause of Diphthongization" (PDF). In Chang, Charles B.; Haynie, Hannah J. (eds.). Proceedings of the 26th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Somerville, Massachusetts: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. pp. 60–68. ISBN 978-1-57473-423-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 24, 2011.

- Boberg, Charles (2004a). "Standard Canadian English". In Hickey, Raymond (ed.). Standards of English: Codified Varieties Around the World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76389-9.

- Boberg, Charles (2004b). "English in Canada: phonology". In Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Vol. 1: Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 351–365. ISBN 3-11-017532-0.

- Boberg, Charles (2008). "Regional phonetic differentiation in Standard Canadian English". Journal of English Linguistics. 36 (2): 129–154. doi:10.1177/0075424208316648. S2CID 146478485.

- Boyce, S.; Espy-Wilson, C. (1997). "Coarticulatory stability in American English /r/" (PDF). Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 101 (6): 3741–3753. Bibcode:1997ASAJ..101.3741B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.16.4174. doi:10.1121/1.418333. PMID 9193061. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 1997.

- Bonfiglio, Thomas Paul (2002). Race and the Rise of Standard American. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017189-1.

- Delattre, P.; Freeman, D.C. (1968). "A dialect study of American R's by x-ray motion picture". Linguistics. 44: 29–68.

- Ennser-Kananen, Johanna; Halonen, Mia; Saarinen, Taina (2021). ""Come join us and lose your accent!" Accent modification courses as hierarchization of international students". Journal of International Students. 11 (2): 322–340. doi:10.32674/jis.v11i2.1640. eISSN 2166-3750. ISSN 2162-3104.

- Duncan, Daniel (February 10, 2016). "'Tense' /æ/ is still lax: A phonotactics study". In Hansson, Gunnar Ólafur; Farris-Trimble, Ashley; McMullin, Kevin; Pulleyblank, Douglas (eds.). Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Meeting on Phonology. Annual Meetings on Phonology. Vol. 3. Washington, D.C.: Linguistic Society of America (published June 21, 2016). doi:10.3765/amp.v3i0.3653.

- Gordon, Matthew J. (2004). "The West and Midwest: phonology". In Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Vol. 1: Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 338–350. ISBN 3-11-017532-0.

- Hallé, Pierre A.; Best, Catherine T.; Levitt, Andrea (1999). "Phonetic vs. phonological influences on French listeners' perception of American English approximants". Journal of Phonetics. 27 (3): 281–306. doi:10.1006/jpho.1999.0097.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- Kövecses, Zoltan (2000). American English: An Introduction. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55-111229-9.

- Kretzschmar, William A. Jr. (2004). "Standard American English pronunciation". In Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Vol. 1: Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 257–269. ISBN 3-11-017532-0.

- Labov, William (2007). "Transmission and Diffusion" (PDF). Language. 83 (2): 344–387. doi:10.1353/lan.2007.0082. JSTOR 40070845. S2CID 6255506. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2005.

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 187–208. ISBN 978-3-11-016746-7.

- Lindsey, Geoff (1990). "Quantity and quality in British and American vowel systems". In Ramsaran, Susan (ed.). Studies in the Pronunciation of English: A Commemorative Volume in Honour of A.C. Gimson. Routledge. pp. 106–118. ISBN 978-0-41507180-2.

- Roca, Iggy; Johnson, Wyn (1999). A Course in Phonology. Blackwell Publishing.

- Rogers, Henry (2000). The Sounds of Language: An Introduction to Phonetics. Essex: Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-0-582-38182-7.

- Seabrook, John (May 19, 2005). "The Academy: Talking the Tawk". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- Shitara, Yuko (1993). "A survey of American pronunciation preferences". Speech Hearing and Language. 7: 201–232.

- Silverstein, Bernard (1994). NTC's Dictionary of American English Pronunciation. Lincolnwood, Illinois: NTC Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8442-0726-1.

- Thomas, Erik R. (2001). An acoustic analysis of vowel variation in New World English. Publication of the American Dialect Society. Vol. 85. Duke University Press for the American Dialect Society. ISSN 0002-8207.

- Thomas, Erik R. (2004). "Rural Southern white accents". In Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Vol. 1: Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 300–324. ISBN 3-11-017532-0.

- Van Riper, William R. (2014) [1973]. "General American: An Ambiguity". In Allen, Harold B.; Linn, Michael D. (eds.). Dialect and Language Variation. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4832-9476-6.

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Vol. 1: An Introduction (pp. i–xx, 1–278), Vol. 3: Beyond the British Isles (pp. i–xx, 467–674). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511611766. ISBN 0-52129719-2, 0-52128541-0.

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Zawadzki, P.A.; Kuehn, D.P. (1980). "A cineradiographic study of static and dynamic aspects of American English /r/". Phonetica. 37 (4): 253–266. doi:10.1159/000259995. PMID 7443796. S2CID 46760239.

- Zhou, Xinhui; Espy-Wilson, Carol Y.; Boyce, Suzanne; Tiede, Mark; Holland, Christy; Choe, Ann (2008). "A magnetic resonance imaging-based articulatory and acoustic study of "retroflex" and "bunched" American English /r/". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 123 (6): 4466–4481. Bibcode:2008ASAJ..123.4466Z. doi:10.1121/1.2902168. PMC 2680662. PMID 18537397.

Further reading

[edit]- Jilka, Matthias. "North American English: General Accents" (PDF). Stuttgart: Institut für Linguistik/Anglistik, University of Stuttgart. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2014.