St Briavels

| St Briavels | |

|---|---|

St Briavels Castle | |

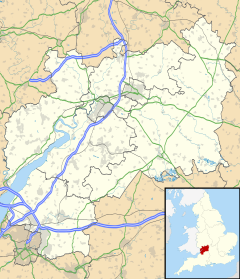

Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 1,192 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SO559044 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LYDNEY |

| Postcode district | GL15 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

St Briavels (pronounced Brevels, once known as 'Ledenia Parva' (Little Lydney)),[2] is a medium-sized village and civil parish in the Royal Forest of Dean in west Gloucestershire, England; close to the England-Wales border, and 5 miles (8 km) south of Coleford. It stands almost 800 feet (240 m) above sea level on the edge of a limestone plateau above the valley of the River Wye, above an ancient meander of the river. To the west, Cinder Hill drops off sharply into the valley. It is sheltered behind the crumbling walls of the 12th century St Briavels Castle.[3]

History

[edit]Little is known about the origin of St Briavels. The name is thought to be from a much-travelled early Christian missionary, Brioc, whose name also appears in places as far afield as Cornwall and Brittany.[4]

Later King Offa of Mercia built Offa's Dyke from the mouth of the River Wye near Chepstow to Prestatyn and local remains can still be seen in the nearby Hudnalls Wood.[5] The Normans thought it an ideal site for one of the many castles built from Chepstow to Chester to check the intrusion of the warlike Welsh tribesmen from the Welsh Kingdom of Gwent into the more peaceful areas east of the Severn and Wye rivers.[6] At Windward, the highest point in the parish, the land rises to 800 feet (240 m) above sea level; St Briavels Castle itself is somewhat lower at 600 feet (180 m) and nestles into the hillsides, with a commanding view of the Wye Valley between Tintern and Redbrook.[7][8]

The castle and St Mary's Parish Church, built in 1089, must have been the site of a considerable community, for the castle was the home of the Constable of the Forest of Dean, a region stretching northwards and eastwards toward the city of Gloucester. Cut off from the rest of England by the tidal Severn River to the east and the treacherous tidal Wye to the west, the Forest was in many ways more isolated than most other parts of the country. As a result, this area produced a culture, language and way of living peculiarly its own. The Forest is full of ancient customs and traditions.

Between the 11th century and 13th centuries the shire counties were split into hundreds. The hundred of St Briavels is the largest in the Forest of Dean and its boundaries approximate to the Forest boundaries.

The village was garrisoned by Miles of Gloucester for King Henry I as early as 1130. The castle was later granted to him with the Forest of Dean in July 1141 when he was made Earl of Hereford. In 1155 the castle and the Forest of Dean were held by the Crown after the revolt of Roger Fitzmiles, 2nd Earl of Hereford. It then remained as a Crown possession for the rest of the Middle Ages. The castle has been a hunting lodge of King John of England, and was also visited by Henry II, who made the castle the administrative and judicial centre for the Forest of Dean.

Between 1876 and 1959, while industry was booming in the Forest of Dean, St Briavels was served by the Wye Valley Railway, and St Briavels Station was situated a mile away near Bigsweir bridge.

Freemining

[edit]Coal mining, iron ore extraction, stone quarrying and forestry with Verderers have all been important primary sources of income in the Forest of Dean.

In the Middle Ages, local miners were highly valued for their digging skills during military campaigns. It is said that, after a particularly successful job undermining the foundations of Berwick Castle at Berwick-on-Tweed, King Edward I granted 'Free-Mining' status to all Forest of Dean coal and ore miners.[9] This authority gave Freeminers the right to dig for minerals anywhere in the Forest of Dean except beneath churchyards, orchards and gardens. To be a Freeminer, an individual has to be "born and abiding within the 'Hundred of St Briavels', of the age of 21 and upwards who shall have worked for a year and a day in a coal or iron ore mine or stone quarry within the Hundred".

In the late middle ages and early modern period open cast stone mining was prevalent in the woods to the west of the village.[10] Many millstones used in the mills and cider presses of the time were quarried in the Hudnalls and rolled down the hillside to be transported away by barges on the River Wye. Between the 16th century and 18th century timber from the Forest was heavily relied upon for the construction of ships - and almost became exhausted, supplying to the demands of Drake, Raleigh and Nelson.

A Forester, is a resident natural of the Forest of Dean, born within the ancient administrative area of the Hundred of St Briavels. There are still several traditional Forester families living and working in the area keeping the ancient traditions and rights alive.

Freemining, free roaming sheep grazed on common land, and grazing of pigs in the Forest, are rights and responsibilities extended to the people of St Briavels that are still exercised today, although more so elsewhere in the Forest of Dean.

Other peculiarities to the area include the ancient right for 'sheep badgers' to let their flocks roam freely and pigs were also allowed to forage freely in the Forest. Firewood was also allowed to be gathered from the local Hudnalls wood.

Amenities and village life

[edit]

The village has one pub - The George, a junior school, a church,[11] two chapels and a doctors' surgery. It also has a well regarded village shop and delicatessen called The Pantry operating from a small building opposite The George. The Congregational church, dating from the 1870s, has Gothic Revival architecture.

Village life today is centred on the school, church, the Pavilions, Assembly Rooms, The George and the Pantry. The Assembly Rooms has a hall with a stage for entertainment and special events for the local close knit community. It also has a small office for hire with Internet and telephone options. Today the Pavilions hold a very popular and well established monthly 'Local Produce and Suppliers Market', a local farmers' market offering a fine selection of organic vegetables, rare breed pedigree pork, award-winning local cheeses, cider, wine, honey and a range of delicacies.[12]

The St Briavels Assembly Rooms are used by the community for classes, playgroups and various events.[13] A recent grant from DEFRA of £94,000 is currently being spent on updating the Rooms for increased usage.

The general character of the village is typified by a mid 19th century core, complemented to the east by a large number of houses built during the 1970s.[14] Although many residents now no longer work in the area the village retains a relatively vibrant community.

The St Briavels Bread and Cheese Dole tradition is said to date back to the time of Miles de Gloucester, 1st Earl of Hereford (then lord of the Forest of Dean) in the 12th century. Each year on Whit Sunday bread and cheese is thrown from the wall of the castle to local 'Dole Claimers' dressed in medieval costume.[15] 'Dole claimers' could be anyone who paid a penny to the incumbent Earl of Hereford entitling them to gather firewood from the nearby Hudnalls wood. Some believe in the power of these edible morsels and preserve them for good luck (miners originally used them as charms to protect against accidents underground). Today some people choose to place them in matchboxes and rest them under their pillow to inspire dreams of the future.

An annual summer fête, known as 'The Carnival', attracts large crowds and is usually held on the second Saturday afternoon in June. Five carnival floats gather and fancy dress contestants congregate around the village green. The floats include St Briavels School, St Briavels Infants, St Briavels Juniors, St Briavels Playgroup and the Carnival Queen Float. The floats then process through the village, finally parking at the bottom of the recreation ground.[16]

A community group called 'Heartbeat St. Briavels' has been set up to provide and maintain defibrillators throughout the village.[17][18]

Governance

[edit]The village is a populous part of 'Newland and St Briavels' electoral ward. This ward starts in the north at Newland and stretches south to St. Briavels. The total ward population taken at the 2011 census was 3,297.[19]

Surrounding parish

[edit]Upper Meend and Lower Meend are locales situated on the west of the village on the slope leading down to the River Wye. Nearby hamlets and settlements include St. Briavels Common (which has not been common land since the inclosure acts, but retains its name), Cold Harbour (an old English place name),[20][21] Mork, the Fence, the Hudnalls, and Triangle, which lies towards Brockweir. The villages of Llandogo, Penallt and Whitebrook lie on the Welsh side of the valley, in Monmouthshire. At the base of the valley, the Bigsweir Bridge across the Wye is one of the world's first iron bridges, dating from 1827.

Railways

[edit]St Briavels railway station was a station along the Wye Valley Railway. It was built in 1876 during the construction of the line on the Monmouthshire side of the River Wye at Bigsweir, and was intended to serve the nearby villages of St Briavels, across the river in the Forest of Dean, and Llandogo, which is further down the Wye Valley. The station was renamed three times during its life: firstly Bigsweir Station, then St Briavels and Llandogo Station, and finally St Briavels Station.[22] The station was closed to passenger services on 5 January 1959 and the line closed to freight in 1964.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ "Parish population 2011". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Vol.9, 1884, p.35

- ^ "St Briavels Castle". Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ Ekwall, Eilert (1960). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-19-869103-7.

- ^ "Offa's Dyke: section on St Briavels Common, immediately south of Sittingreen". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "History of St Briavel's Castle". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "St Briavel's Castle". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "St Briavels Castle and curtain wall". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Breakspear, Mike (1998). "The Forest of Dean Free Miners". Journal of the Cerberus Spelaeological Society. 24 (3). Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Hoyle, Jon (2008). "The Forest of Dean Gloucestershire. Archaeological Survey. Appendices" (PDF). Gloucestershire County Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Church of St Mary". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "St. Briavels Local Produce Market". St. Briavels. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "St. Briavels Assembly, Recreation & Reading Rooms". St. Briavels. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Roy Parkhouse. "St Briavels - St Bruel's Close (C) Roy Parkhouse :: Geograph Britain and Ireland". Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "St Briavels Bread & Cheese Scramble". Calendar Customs. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "St Briavels set for carnival capers". Forest of Dean and Wye Valley Review. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "New defibrillators are hoped will save lives in Forest of Dean village". Gloucester Citizen. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Aims - Heartbeat St. Briavels". Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Newland and St Briavels ward 2011". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ "Cold Harbor.--". The New York Times. 15 March 1885. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Re: Cold Harbour". Archived from the original on 3 November 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ a b B. M. Handley and R. Dingwall, The Wye Valley Railway and the Coleford Branch, 1982, ISBN 0-85361-530-6

Further reading

[edit]- Remfry, P.M., Saint Briavels Castle, 1066 to 1331 (ISBN 1-899376-05-4)