Tau cross

The tau cross is a T-shaped cross, sometimes with all three ends of the cross expanded.[1] It is called a "tau cross" because it is shaped like the Greek letter tau,[2] which in its upper-case form has the same appearance as the Latin letter T.

Another name for the same object is Saint Anthony's cross[3] or Saint Anthony cross,[4] a name given to it because of its association with Saint Anthony of Egypt.

It is also called a crux commissa,[5] one of the four basic types of iconographic representations of the cross.[6]

Tau representing an execution cross

[edit]

The Greek letter tau was used as a numeral for 300. The Epistle of Barnabas (late first century or early second) gives an allegorical interpretation of the number 318 (in Greek numerals τιη’) in the text of Book of Genesis 14:14 as intimating the crucifixion of Jesus by viewing the numerals ιη’ (18) as the initial letters of Ἰησοῦς, Iēsus, and the numeral τ’ (300) as a prefiguration of the cross: "What, then, was the knowledge given to him in this? Learn the eighteen first, and then the three hundred. The ten and the eight are thus denoted—Ten by Ι, and Eight by Η. You have [the initials of the name of] Jesus. And because the cross was to express the grace [of our redemption] by the letter Τ, he says also, 'Three Hundred'. He signifies, therefore, Jesus by two letters, and the cross by one."[7]

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215) gives the same interpretation of the number τιη’ (318), referring to the cross of Christ with the expression "the Lord's sign": "They say, then, that the character representing 300 is, as to shape, the type of the Lord’s sign, and that the Iota and the Eta indicate the Saviour’s name."[8]

Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 240) remarks that the Greek letter τ and the Latin letter T have the same shape as the execution cross: "Ipsa est enim littera Graecorum Tau, nostra autem T, species crucis".[9]

In the Trial of the Court of the Vowels of non-Christian Lucian (125 – after 180), the Greek letter Sigma (Σ) accuses the letter Tau (Τ) of having provided tyrants with the model for the wooden instrument with which to crucify people and demands that Tau be executed on his own shape: "It was his body that tyrants took for a model, his shape that they imitated, when they set up the erections on which men are crucified. Σταυρός the vile engine is called, and it derives its vile name from him. Now, with all these crimes upon him, does he not deserve death, nay, many deaths? For my part I know none bad enough but that supplied by his own shape—that shape which he gave to the gibbet named σταυρός after him by men"[10]

The Greek word σταυρός, which in the New Testament refers to the structure on which Jesus died, appears as early as AD 200 in two papyri, Papyrus 66 and Papyrus 75 in a form that includes the use of a cross-like combination of the letters tau and rho.[11][12][13] This tau-rho symbol, the staurogram, appears also in Papyrus 45 (dated 250), again in relation to the crucifixion of Jesus. In 2006 Larry Hurtado noted that the Early Christians probably saw in the staurogram a depiction of Jesus on the cross, with the cross represented (as elsewhere) by the tau and the head by the loop of the rho, as had already been suggested by Robin Jensen, Kurt Aland and Erika Dinkler.[11] In 2008 David L. Balch agreed, adding more papyri containing the staurogram (Papyrus 46, Papyrus 80 and Papyrus 91) and stating: "The staurogram constitutes a Christian artistic emphasis on the cross within the earliest textual tradition", and "in one of the earliest Christian artifacts we have, text and art are combined to emphasize 'Christus crucifixus'".[12] In 2015, Dieter T. Roth found the staurogram in further papyri and in parts of the aforementioned papyri that had escaped the notice of earlier scholars.[13]

In the view of Tertullian[14] and of Origen (184/185 – 253/254)[15] the passage in Ezekiel 9:4 in which an angel וְהִתְוִיתָ תָּו עַל־מִצְחֹות הָאֲנָשִׁים, "set a mark [tav; after the cross-shaped Phoenician and early Hebrew letter] on the forehead of the men" who are saved was a prediction of the Early Christian custom of repeatedly tracing on their own foreheads the sign of the cross.

Association with Saint Anthony of Egypt

[edit]

The Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony, known as the Antonines, were a Catholic religious order of the Latin Church founded at the end of the 11th century. They wore a black religious habit marked with a blue tau. This habit became associated with their patron saint, Anthony of Egypt, who accordingly was represented as bearing on his cloak a cross in the form of a tau.

Through its association with the Antonines, this cross became known as Saint Anthony's cross, as the disease of ergotism, to whose treatment the Antonines devoted themselves more particularly, became known as Saint Anthony's fire.

In about 1500 the Antonines still had 370 hospitals, but with the identification of the fungus that caused ergotism, the reduction of epidemics and the competition from the hospitals of the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (generally known as the Knights of Malta) their numbers decreased. Their last house in Europe was finally closed in 1803.[16]

Another explanation proposed for the association of the tau cross with Saint Anthony is that the tau cross was a stylized representation of the saint's staff, topped by a horizontal bar, on which he supported himself when old. A staff of that kind is represented in his hand in a painting by the German Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470 – 1528) on an outer panel of his Isenheim Altarpiece. In this painting the saint remains tranquil in spite of being threatened by a fearsome demon depicted as breaking the panes of the window behind him. The saint is not shown as wearing the emblem of the Antonines.[16]

The Antonines survive in the Middle East, especially in Lebanon, as a Maronite Church order with 21 monasteries and many schools and seminaries. They still use the bright blue tau cross on their black habits.[16]

With the disappearance in the Western Church of the Hospital Brothers of Saint Anthony, the tau cross is now most commonly associated with the Franciscan Order and its founder, Saint Francis of Assisi, who adopted it as his personal sign after hearing Pope Innocent III talk about the Tau symbol.[17] It is now used as a symbol of the Secular Franciscan Order.[18]

In Franciscanism

[edit]The cross's use in Franciscanism dates back to St. Francis of Assisi himself, who used it as his signature and personal seal. During the time of Francis and from the Fourth Lateran Council, called by Pope Innocent III, the tau was a symbol widely used by the Catholic Church, in general, as a sign of conversion and sign of the cross.

In inaugurating that Council, Innocent III preached on Ezekiel 9 and called all Christians to do penance under the sign of the tau, a sign of conversion and the sign of the cross. As Omer Englebert recounts in his biography of Francis, the Pope, after describing the sad situation of the Holy Places trampled by the Saracens, lamented the scandals that discredited the flock of Christ and threatened it with divine punishment if it was not amended. He evoked the vision of Ezekiel, when the Lord, patience exhausted, exclaims with a powerful voice:[19][page needed]

"'Come near, you who watch over the city; come near with the instrument of extermination in your hands.' And behold, six men arrived with two whips in their hands. Among them was a man dressed in linen, with a writing-message around his waist. And Yahweh said to him: 'Go through Jerusalem, and mark with a tau the foreheads of the righteous who are in it.' And he said to the other five: 'Go through the city after him, and mercilessly exterminate as many as you find; but do not touch anyone who is marked with the tau.'" ... Who are – continued the Pope – the six men in charge of divine vengeance? Those are you, Council Fathers, who, using all the weapons you have at hand: excommunications, dismissals, suspensions and interdicts, you have to relentlessly punish how many are not marked with the propitiatory tau and are obstinate in dishonoring Christianity.

In his Lateran speech, Innocent III had marked with the tau sign three classes of predestined: those who enlisted in the crusade; those who, prevented from crossing paths, fight against heresy; finally, the sinners who really commit themselves to reforming their lives.

Francis, who participated in the council as superior general of an order approved by the church, must have taken Innocent III's invitation very seriously, since, according to his companions and his first biographers, he loved and revered the tau, "because it represents the cross and means true penance". At the beginning of any activity, he crossed himself with said sign, preferring it to any other sign, and painted it on the walls of the cells. In his conversations and sermons he often recommended it, and drew it as a signature in all his letters and writings, "as if all his concern was to engrave the sign of the tau, according to the prophetic saying, on the foreheads of the men who moan and weep, truly converted to Christ Jesus."[citation needed]

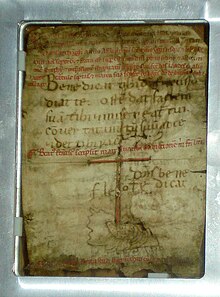

Among Francis's autograph manuscripts in which he signs with the tau is his famous "Blessing to Brother Leo", a relic that is preserved in the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi.

Crux commissa

[edit]In discussions of Roman execution crosses, the tau cross is called the crux commissa. This term was invented by Justus Lipsius (1547–1606),[20] who used it to distinguish this T-shaped cross from the now more familiar †-shaped cross and the saltire X-shaped cross.[21]

Gallery

[edit]-

Tau cross pendants from late medieval (early Tudor era, c. 1485) England

-

The Cross of Tau used to build patterns in a window at the Convent of Saint Anthony near Castrojeriz, Spain

-

Cross Inneenboy (replica) near Corofin, County Clare, Ireland

-

Modern "Franciscan" Tau pendant

-

Saint Anthony's cross on the former Antonine hospital in Höchst am Main

-

Baptismal font (14th century) at Fivizzano with the Saint Anthony's cross symbol of the Antonine canons

-

Tau cross, Tory Island, County Donegal, Ireland

See also

[edit]- Christian cross

- Crucifix

- Crux simplex

- Descriptions in antiquity of the execution cross

- Forked cross

- Taphos symbol (tau plus phi)

References

[edit]- ^ Merriam-Webster: tau cross

- ^ Collins English Dictionary: tau cross

- ^ Collins English Dictionary: Saint Anthony's cross

- ^ Oxford Dictionaries: St Anthony cross

- ^ Merriam-Webster: crux commissa

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Cross (religious symbol)

- ^ The Epistle of Barnabas, IX

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, The Stromata, book VI, chapter 11

- ^ Adversus Marcionem, liber III, cap. XXII

- ^ Trial in the Court of Vowels

- ^ a b Larry W. Hurtado, "The Staurogram in Early Christian Manuscripts: the earliest visual reference to the crucified Jesus?" in Thomas J. Kraus, Tobias Nicklas (editors), New Testament Manuscripts: Their Text and Their World (Brill, Leiden, 2006), pp. 207–226

- ^ a b David L. Balch, Roman Domestic Art and Early House Churches (Mohr Siebeck 2008), pp. 81–83

- ^ a b Dieter T. Roth, "Papyrus 45 as Early Christian Artifact" in Mark, Manuscripts, and Monotheism: Essays in Honor of Larry W. Hurtado (Bloomsbury 2015), pp. 121–125

- ^ "He signed them with that very seal of which Ezekiel spake: 'The Lord said unto me, Go through the gate, through the midst of Jerusalem, and set the mark Tau upon the foreheads of the men.' Now the Greek letter Tau and our own letter T is the very form of the cross, which He predicted would be the sign on our foreheads in the true Catholic Jerusalem" (Tertullian, The Five Books against Marcion, book III, chapter XXII).

- ^ Jacobus C. M. van Winden, Arché: A Collection of Patristic Studies (Brill 1997), p. 114

- ^ a b c Commune de Saint-Antoine-le-château, Les Antonins: Une histoire documentaire et iconographique, pp. 9–11

- ^ "The Tau Cross – An Explanation". The Franciscans. franciscanfriarstor.com. Archived from the original on 2010-10-05. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ^ Secular Franciscan Order

- ^ Englebert, Omer (1979). Saint Francis of Assisi: A Biography. Ann Arbor: Servant Books. ISBN 978-0-89283-071-8 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gunnar Samuelsson, Crucifixion in Antiquity (Mohr Siebeck 2013, pp. 3–4 and 295) ISBN 978-31-6152508-7

- ^ Justus Lipsius, De Cruce (Antwerp 1595) book I, chapter VIII, pp. 15–17

External links

[edit]- Tau cross on Tory Island, Ireland