Spring Street (Los Angeles)

Spring Street Financial District | |

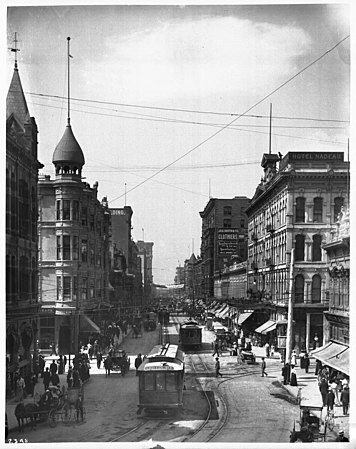

Spring Street looking north from Hotel Hayward | |

| Location | 354–704 S. Spring St., Los Angeles, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°2′48″N 118°14′59″W / 34.04667°N 118.24972°W |

| Built | 1902 |

| Architect | Morgan, Walls & Morgan; Parkinson, John |

| Architectural style | Chicago, Classical Revival, Moderne |

| NRHP reference No. | 79000489[1] |

| Added to NRHP | August 10, 1979 |

Spring Street in Los Angeles is one of the oldest streets in the city. Along Spring Street in Downtown Los Angeles, from just north of Fourth Street to just south of Seventh Street is the NRHP-listed Spring Street Financial District, nicknamed Wall Street of the West,[2][3] lined with Beaux Arts buildings and currently experiencing gentrification. This section forms part of the Historic Core district of Downtown, together with portions of Hill, Broadway, Main and Los Angeles streets.

Name

[edit]Originally named Calle Primavera, Spring Street was renamed in 1849 by city surveyor Edward Ord. He named the street after a woman he was wooing, one whom he'd given the nickname “mi primavera, my springtime”.[4]

Geography

[edit]Spring Street consists of 3 sections:[5]

- The original section of Spring Street begins in the south from the intersection of 9th Street. At 7th Street, the Spring Street Financial District begins, ending just after 4th Street. This section of Spring ends at a three-way junction with Cesar Chavez Avenue.

- One block east of this junction, N. Spring Street continues northeast through Chinatown, terminating at College Street. This section was originally called Calle de la Eternidad (Eternity Street),[6] then Upper Main Street[7] and then by 1897, San Fernando Street.[8]

- One block east of that junction, another portion of North Spring Street continues northeast, at a gradually more easterly angle, crosses the Los Angeles River into Lincoln Heights, and terminates at a junction with North Broadway and Avenue 18. This section originally bore the names San Fernando Street, Olympia Street and Downey Street.[7]

Historic District

[edit]The historic district includes 23 financial structures, including the city's first skyscraper, and three hotels all located along a stretch of South Spring Street from just north of Fourth Street to just south of Seventh Street. In the first half of the 20th century, this stretch of Spring Street was the financial center of Los Angeles, with the important banks and financial institutions being concentrated there. At least ten of the buildings in the district were designed in whole or in part by John Parkinson, who designed many of the city's landmark buildings in the early 20th century, including the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, Los Angeles City Hall, Bullocks Wilshire, and Union Station. Ten of the buildings in the district have been designated as Historic-Cultural Monuments by the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission.

Due to the large percentage of historic bank and financial buildings that remain intact in the district, the area was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. The Los Angeles Conservancy offers walking tours of the Spring Street Financial District on the fourth Saturday of each month at 10 a.m.; the tour lasts approximately 2-1/2 hours and costs $10 for the general public (reduced rate for Conservancy members).[9]

History

[edit]Early days

[edit]The city's central business district (CBD) in the 1880s and 1890s lay further north near South Spring and Temple Streets.

The street can claim credit as the birthplace of the motion picture business in Los Angeles. In 1898, Thomas Edison filmed a 60-second film titled "South Spring Street Los Angeles California", mounting a giant camera on a wagon to film the bustling action along South Spring Street.[3][10]

Wall Street of the West

[edit]In the early 1900s, the city center began spreading south, and the city's banks and financial institutions began concentrating along South Spring Street. The first two important buildings to make the move south were the Hellman and Continental Buildings, with the Continental Building being considered the city's first skyscraper.[11][3]: 1 In 1911, the Los Angeles Times boasted about the building boom on Spring Street:

The visitor to this city can at this moment observe skyscrapers in all stages of construction. It is a study which will provide the most comprehensible kind of answer to the query as to why Los Angeles is leading San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Baltimore, Detroit, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Boston, Buffalo and all other cities of anything near her in building activity as revealed by the monthly expenditures for construction work.[12]

The building boom along South Spring Street continued into the 1920s as the population and economy of Los Angeles boomed. South Spring Street remained the city's financial center even after World War II.

Decline (1970s–1980s)

[edit]In the 1960s, many of the banks and financial institutions began moving to the western part of the downtown area, along Figueroa Street and Wilshire Boulevard.[2] By the early 1980s, South Spring Street had become known for "transients who sleep in doorways and urinate on sidewalks."[13] In 1982, the Los Angeles Times commented on the district's decline from "Wall Street of the West" to a blighted area with empty office buildings lining both sides of the street:

"When the banks and law firms moved to the 'Gold Coast' typified by Arco Towers, six blocks to the west, Spring Street plummeted to become a neighborhood of hoodlums, derelicts and winos—a neighborhood of echoing buildings full of absolutely nothing above the ground floor."[14]

Redevelopment and regentrification

[edit]Since the early 1980s, South Spring Street has been the subject of numerous redevelopment projects. In recent years, numerous art galleries have moved into the old financial district, which is now known as Gallery Row. Many of the old bank buildings have also been converted into upscale lofts. As wealthier residents have moved into the district's lofts, older residents and artists have complained about the increased rents. One artist who had lived in the district for years said:

The real problem with downtown lately, Gronk and his friends half-jokingly agreed is 'those people.' Westsiders. Trust-fund babies. New tenants who demand their bohemian pleasures be liberally sweetened with suburban amenities. Landlords who previously recruited artists to help make downtown 'safe' for gentrification, then jacked up their rents so only lawyers and screenwriters could afford it.[15]

Beaux Arts architecture as the district's enduring strength

[edit]The strength of the district remains its period architecture. Many of the Beaux Arts façades along Spring Street remain virtually intact, making the district a popular shooting location for motion picture and television productions seeking authentic period cityscapes.[3] In 1985, noted Los Angeles Times columnist Jack Smith pointed to the Spring Street Financial District as proof that "Los Angeles was never the cultural wasteland it was alleged to be."[16] He hailed the district's "financial palaces" as "a solid architectural achievement" which give the street "beauty, strength, unity and dignity."[16]

Buildings and sites in the district

[edit]Notable buildings in the district (from north to south) include:[2]

- Hellman Building

- Northeast corner of 4th and Spring – Built in 1902, the Hellman and Continental Buildings were the first major structures to anchor the Spring Street Financial District. The Hellman Building, now known as Banco Popular, is an eight-story brick and concrete structure designed by Alfred Rosenheim. In 1998, Gilmore Associates announced plans to convert the Hellman Building, the Continental Building, and the San Fernando Building into 230 lofts.[17][18][19][20] The converted buildings consisted of large, open lofts with high ceilings and no interior walls except for the bathrooms. The conversion was designed by architect Wade Killefer, who noted: "What lends these buildings to residential use is lots of windows and high ceilings, offering wonderful light."[19] The combined project became known as the Old Bank District lofts.[21]

- The Continental Building

- 408 S. Spring Street – Built in 1902, the Continental Building was originally known as the Braly Building. The 12-story building was designed by John Parkinson and is considered the first "skyscraper" in Los Angeles. It was the tallest building in Los Angeles until 1907. It is known for its highly ornamental cornice and bands. The Continental Building was converted into lofts as part of Tom Gilmore's Old Bank District lofts project. It was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #730) in 2002.

- El Dorado Hotel

- 416 S. Spring Street – Originally known as the Hotel Stowell, the 12-story hotel was built in 1913 and designed by Frederick Noonan with a highly stylized and brightly colored facade, enameled brick and terra cotta. Batchelder tiles are used extensively in the hotel and lobby. Shortly after the hotel opened, Charlie Chaplin lived at the Stowell, which he described as "a middle-rate place but new and comfortable." Chaplin later told a story about receiving a telephone call while there concerning an appearance for which he was to be paid $25,000. Chaplin recalled: "My bedroom window opened out on the well of the hotel, so that the voice of anyone talking resounded through the rooms. The telephone connection was bad, 'I don't intend to pass up twenty-five thousand dollars for two weeks’ work!' I had to shout several times. A window opened above and a voice shouted back: 'Cut out that bull and go to sleep, you big dope!'" In 2008, the building was converted into lofts under the name "El Dorado Lofts."

- Title Insurance Building

- 433 S. Spring Street – Built in 1928, the Title Insurance Building is a ten-story building designed by John and Donald Parkinson in the Zig-Zag Moderne style. The marble lobby includes a mural by Hugo Ballin. The Title Insurance Building was the subject of the district's first major redevelopment project. Architect-developer Ragnar C. Qvale acquired the building in 1979. He took the impressive Art Deco shell and converted the building into the Design Center of Los Angeles, which he leased to wholesale household furniture showrooms. Early 2011, the ground floor of the building became an art gallery and coffee shop, and took the logical name of Groundfloor Gallery & Café.[14] The Title Insurance Building was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #772) in 2003.

- Crocker Bank/Spring Arts Tower

- 453 S. Spring Street – Built in 1914, the 12-story building was designed by Parkinson and Bergstrom. The building was once the Los Angeles headquarters of Crocker Citizens National Bank. Now known as the Spring Arts Tower, the building is part of a movement to convert the old financial district into the city's "Gallery Row." The building's interior features original Art Deco designs, Art Nouveau details, sculptured brass, Italian marble, Batchelder tile, California alder and tiger oak. The building's tenants include artists, designers, architects, film production companies, and law firms. A nightclub called the "Crocker Club" is open on the vault floor.[22] The Last Bookstore is also in the building.

- Rowan Building

- 460 S Spring Street – Built in 1910, the 11-story Rowan Building was originally known as the Chester Building, designed by Parkinson & Bergstrom in a mix of Beaux Arts and Classical styles. Ornate cast iron rosettes hang from the building's cornice, and elegant glazed terra cotta panels cover the facade. During its construction, the Times described it as a "mammoth" structure being built with the most massive steel girders and beams ever used on the West CoaStreet The building, built from 3000 tons of steel, was the largest office in Los Angeles in 1911.[12] During its construction, hundreds of people lined the street "to see the huge crane swinging these titanic metal units of the structural plan into place for the workmen with the air riveters."[12] Built by developer Robert A. Rowan, the Rowan Building once housed many of the city's prominent law offices and stock brokerage firms. It has been known over the years as the Central Fire Proof Building Company and the Chester Building and has been converted into 206 live/work condominium units with retail space on the ground floor.[23] Many interior features including Carrara marble corridor walls and floors, mahogany windows, and detailed Art Deco elevator doors have been preserved.[24]

- Alexandria Hotel

- 210 W. 5th Street – Built in 1906, the eight-story Alexandria Hotel is another building designed by John Parkinson. With 500 rooms, an elaborate wood lobby, and the glamorous Palm Court with its stained glass dome, the Alexandria was the most luxurious hotel in Los Angeles from the time it opened until the Biltmore opened in the mid-1920s.[25] Movie stars and other celebrities, including Mae West, Humphrey Bogart, Rudolph Valentino, Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, Sarah Bernhardt, Enrico Caruso and Jack Dempsey were guests. Charlie Chaplin kept a suite at the Alexandria and did improvisations in the lobby where Tom Mix reportedly rode his horse.[3][25] The carpet in the lobby was called the "million-dollar carpet", because there was purportedly a $1 million worth of business done there every day.[25] It was there that D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks met in 1919 to form United Artists.[3] U.S. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson,[25] and many foreign dignitaries, including King Edward VIII, also stayed at the hotel while visiting Los Angeles. The hotel declined after the Biltmore opened and closed in 1934, with its chandelier and gold leaf covering of the mezzanine lobby being stripped and sold.[25] It reopened in 1937 but declined again in the 1950s, become a transient hotel with the Grand Ballroom being used as a training ring for boxers.[25] Today, the Alexandria has been converted to apartments.[26] The Palm Court in the Alexandria was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #80) in 1971.

- Security Building

- 510 S. Spring Street – Built in 1906, the 11-story steel-frame Security Building was designed in an Italianate style by Parkinson and Bergstrom. When it was built, it was the tallest building in Los Angeles, surpassing the Continental Building. It remained the city's tallest building until 1911. The Security Building has been converted to lofts operated under the name "The Lofts at the Security Building." The Security Building was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #741) in 2003.

- Los Angeles Theater Center

- 514 S. Spring Street – Built in 1916, the one-story building was designed by John Parkinson in a Greek-Revival style with Ionic columns. In addition to the columns, the building is known for its lobby with a large 50 by 100-foot (30 m) stained glass ceiling supported by heavy ornamental bronze cornices and marble walls.[27] It been known over the years as the Security Trust & Savings Building, the Security National Bank Building and the President Trading Company.[14][16][27] In 1985, the building reopened as the Los Angeles Theater Center, a venue with multiple theaters offering live theatrical productions.[28] The converted building has preserved the bank lobby with its stained glass ceiling. The Theater Center met with financial trouble and was forced to close. However, it was later re-opened by the City.[29]

- Spring Arcade Building

- 541 S. Spring Street – Built in 1924, the 12-story, double-wing Arcade Building, designed by architects Kenneth MacDonald and Maurice Couchot, includes a cavernous midblock arcade connecting Spring Street with Broadway. Originally known as the "Mercantile Arcade Building," it was modeled on the Burlington Arcade in London, England. Its three-level, skylighted arcade has been called a space "as regal as almost any other interior space in the city."[14] The tower on top of the building once supported the antenna of the radio station KRKD ("RKD" = Arcade), from which Aimee Semple McPherson preached her message.[30] The ups and downs of the district were reflected in the sales of the Arcade Building. As the area fell into decline, it sold in 1977 for $300,000. Five years later, as redevelopment projects fueled speculation in Spring Street properties, it sold for $4.5 million—15 times its 1977 sale price.[14] The 195,000-square-foot (18,100 m2) building was converted into 142 loft apartments as part of a $15-million renovation.[31]

- Lloyd's Bank

- 548 S. Spring Street – Built in 1913, the 12-story Lloyd's Bank was designed in the Commercial style by William Curlett & Son. The building has been converted into lofts and is now known as SB Lofts. The music video of I'll Be Over You was shot with the band, Toto, playing on the rooftop of this building.

- Pacific Southwest Bank

- NW corner of 6th and Spring – Built in 1910, the 11-story Pacific Southwest Bank was designed by Parkinson & Bergstrom in the Classical style with fluted columns. The building has been converted into lofts and is now known as SB Manhattan.

- United California Bank

- 600 S. Spring Street – Built in 1961 and designed by Claud Beelman & Associates, this contemporary glass and concrete building is one of the few nonconforming intrusions in the Spring Street Financial District. It was the first skyscraper to be built after the city's building height limit was lifted. City planners hoped it would solidify Spring Street as the city's financial center, but an exodus of banks and financial institutions began in the 1960s.[32][33]

- Hotel Hayward

- 601 S. Spring Street – Built in 1905, the nine-story Hotel Hayward was designed by Charles Whittlesey. There is a 14-story addition on the western side that was added in 1925 and designed by John and Donald Parkinson. The Hotel Hayward plays a part in the 2007 movie "Transformers," as the climactic battle between "Megatron" and "Optimus Prime" takes place on the street in front of The Hotel Hayward. The hotel was built on the site of the original Ralphs Brothers grocery store, when the area was still south of the central business district and was still mostly residential. That store would give rise to today's large chain of supermarkets.

- Los Angeles Stock Exchange Building

- 618 S. Spring Street – Built in 1929, the eleven-story Los Angeles Stock Exchange Building was designed by Samuel Lunden in the Moderne style. Ground was broken in October 1929, just as the Great Depression hit, and when the Los Angeles Stock Exchange opened its doors there in 1931, the country was deep into the Depression. There are three bas-relief panels carved by Salvatore Cartaino Scarpitta into the granite above the building's entrance. The panels portray the elements of a capitalist economy. The large central panel, "Finance", displays capitalists. The "Production" panel shows an aircraft engine, a steel worker pouring molten metal and a worker stirring it. The "Research and Discovery" panel shows oil derricks, factories, a chemist conducting an experiment and a man kneeling in a library reading a book. The interior is wonderfully preserved, and has ancient Near East and Native Indian influences by the designer Julian Ellsworth Garnsey. On the entrance lobby's ceiling the Wilson Studio created four sculpted figures representing: Speed (Mercury), Accuracy (the archer), Permanence (a figure contemplating the universe), and Equality (the figure bearing scales). The highlight of the interior was its massive 90' x 74' balconied trading floor with a forty-foot ceiling and sixty-four booths. On fifth floor was a clearing-house with a statistics department, an auditorium, and a lecture room. Offices occupied floors six through nine, and the top two floors included: a club with a library, a card room, a billiard room, and reading rooms. The basement held a 2,660-sq. ft. printing room and a vault. In 1986, the exchange (by then part of the Pacific Stock Exchange) moved out of the building.[34] In the late 1980s, the Community Redevelopment Agency helped fund a night club that opened in the Exchange Building—called the Stock Exchange, but the club did not survive the 1980s. In late 2008, the building underwent extensive renovations and reopened in 2010 as Exchange LA nightclub. The visually dynamic building and interiors are frequently used for location filming, and has been featured in The Big Lebowski, The Social Network, and numerous television shows and commercials. Special events include corporate parties, product debuts, and fashion shows. The Stock Exchange Building was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #205) in 1979.

- E.F. Hutton Building

- 623 S. Spring Street – Built in 1931, the 12-story Zig-Zag Moderne E.F. Hutton Building once housed E.F. Hutton's big board. The Hutton and California Canadian Bank were the first office buildings to be converted into residences.[35] In 1984, the Community Redevelopment Agency converted the adjacent towers into 121 condominiums in a project called Premiere Towers. However, when most of the units failed to sell, the agency sold the project to a developer who offered the units for rental—in the process destroying property values for those who had purchased units.[36]

- California Canadian Bank

- 625 S. Spring Street – Built in 1923, the 12-story Neo-Classical building includes terra cotta ornamentation on the top two levels. The building is now part of the Premiere Towers project with the E.F. Hutton Building.

- Mortgage Guaranty Building

- 626 S. Spring Street – Built in 1913, the six-story Mortgage Guaranty Building (also known as the Sassony Building) has a decorative cornice and fluted columns. In 2004, the structure was converted into 36 apartments called "City Lofts" by developer Izek Shomof.[37]

- Banks & Huntley Building

- 632 S. Spring Street – Built in 1930, the Banks & Huntley Building was designed by John and Donald Parkinson in the Moderne style. It is now known as The Nonprofit Center, housing the national and regional offices for MALDEF, a Latino civil rights organization. The building also rents space to other nonprofit organizations providing assistance to minority and underserved communities. The building has been restored to its original Art Deco design.[38] The Banks & Huntley Building was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #631) in 1999.

- Barclays Bank

- 639 S. Spring Street – Built in 1919, the 13-story Barclays Bank was designed by Morgan, Walls & Morgan. The Barclays Bank building was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #671) in 1999.

- A.G. Bartlett Building

- 651 S. Spring Street – Built in 1911, the Bartlett Building was originally known as the Union Oil Building and served as the headquarters of Union Oil Company until 1923.[12][39] The building was designed by Parkinson & Bergstrom.[12] It was also the place where Southwestern Law School got its start in 1911 with a few young men meeting three nights a week to study law with a tutor.[40]

- Bank of America Building

- 650 S. Spring Street – Built in 1924, the 12-story Bank of America Building was designed by Schultze & Weaver. Its facade has Indian limestone and terra cotta in a style reminiscent of Louis Sullivan. The building has been converted into lofts and is now known as SB Spring.[41][42]

- Financial Center Building

- 704 S. Spring Street – Built in 1923, the 13-story Financial Center Building was designed by S. Tilden Norton and Frederick Wallis. The facade has pressed brick and terra cotta.

- I.N. Van Nuys Building

- 210 W. 7th Street – Built in 1911 by the Isaac Newton Van Nuys (a noted banker and owner of much of the San Fernando Valley), the Van Nuys Building is an 11-story building in Classical style with Italianate details. The Times reported in 1911 that the magnificent new building would be "the city's most expensive office building" at $1,250,000.[12] In the early 1980s, City redevelopment agencies spent $24.3 million to convert the Van Nuys Building into 299 units of housing for senior citizens and the handicapped.[13][14] The Van Nuys Building was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #898) in 2007.

- National City Bank of Los Angeles building

Just south of the Historic District but included here for convenience. Built in 1924, the 12-story Beaux-Arts building at 810 S. Spring St. (southeast corner of 8th St.) was designed by Walker & Eisen as the headquarters of National City Bank of Los Angeles,[43] and was designated a Historic Cultural Landmark (HCM #871) in 2007.[44] It was converted from offices to 93 residential units plus retail space in 2008, and was renamed the National City Tower.[45]

Image gallery

[edit]-

Hellman Building, northeast corner of 4th

-

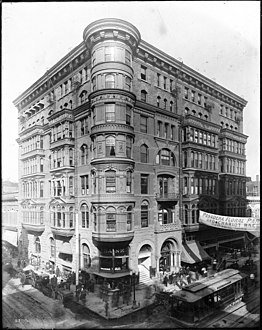

Corner of 4th & Spring in the 1890s

-

Continental Building at #408 when home to the German American Savings Bank, 1908

-

Continental Building, LA's first skyscraper

-

Title Insurance Building at #433

-

Crocker Bank

-

Rowan Building, 131 W. 5th

-

Moderne exterior of the Title Insurance Building at #416

-

Alexandria Hotel, 210 W. 5th

-

Security Building at #510

-

Los Angeles Theater Center at #514

-

Spring Arcade Building at #541

-

Lloyd's Bank at #548

-

1904 panorama including the 600 block of Spring St.; the streetcar is traveling south on Spring, crossing 6th St.

-

Pacific Southwest Bank at northwest corner of 6th

-

Hotel Hayward at #601

-

Los Angeles Stock Exchange at #618

-

Decorations above entrance to E.F. Hutton Building at #623

-

California Canadian Bank hat #625

-

Mortgage Guarantee Building at #626

-

Banks Huntley Building at #632

-

Barclay's Bank at #639

-

Bartlett Building at #651

-

Bank of America at #650

-

Financial Center Building at #704

-

Van Nuys Building, 210 W. 7th

Downtown north of the historic district

[edit]North of the historic district, Spring Street passes through the Civic Center district along government buildings built since the 1920s. However, this area was the heart of the city's business district around the 1880s and 1890s, nearly all of which was demolished.

Gallery

[edit]-

Looking northeast on Spring Street from First Street, 1880s. Asher Hamburger's Peoples Store at center. Towers of the Baker Block are visible in the distance.

-

Looking northeast on Spring Street from First Street, 1890s. Hamburger's Peoples Store now in the Phillips Block at center. Electric streetcars replaced horsecars and the street is paved. Today, this is the site of City Hall.

-

View south on Spring St. from Temple, c.1883–1894. The towers in the background are the Phillips Block; the two larger buildings to its right are the Jones Block and (with turrets) City of Paris. Far right: Allen Block and Harris & Frank's London Clothing Co., with its landmark clock.

West side of Spring south of Temple

[edit]

-

International Savings & Exchange Bank Building (1907) SW corner of Temple/Spring

-

Replica of the Int'l Savings Building façade in the film Safety Last!

-

City of Paris department store, north of Phillips Block and south of Temple, sometime between 1883–1890. Note the cable car which ran 1885–1902.

-

Jones Block, 171–201 N. Spring, west side across from Market St., southern building, c.1880-1885

-

-

Jones Block sometime between 1886–1895 when home to J. W. Robinson's Boston Dry Goods store.

Along the west side of Spring Street were the following buildings. Spring was realigned in the 1920s and now runs west of these sites, and the sites where these buildings once stood are now part of the full city block on which City Hall stands:

- At the southwest corner of Spring and Temple was the Allen Block, between 1883 and 1894 location of Harris & Frank's London Clothing Co., with its landmark clock. The first J. W. Robinson's Boston Dry Goods store was also located in this block from 1883–1886 before moving to the Jones Block slightly south.[46] The Allen Block was replaced by the International Savings & Exchange Bank Building (10 floors, 1907, H. Alban Reaves, Renaissance Revival and Italianate, demolished 1954-5)[47]), southwest corner of Temple and Spring. A replica of its façade featured in the Harold Lloyd film Safety Last!, in a famous scene where Lloyd hangs off a clock near the building's roof. In its later years it housed city health offices and was called the "Old City Health Building".[47]

- City of Paris department store, 203–7 N. Spring, west side between Temple and the Phillips Block. Spring Street now runs west of this site, which is part of City Hall.

- Jones Block

- Built 1882 or -3[48]

and commissioned by Doria Deighton-Jones,[49] demolished in the 1920s to create the City Hall block.

- Post-1890 numbering 171–179 and 201 N. Spring St.,[50]

- Tenants included:

- Los Angeles Herald offices and steam printing plant through 1888[51]

- J. W. Robinson's Boston Dry Goods at #171–173 from 1886 to 1895. Robinson's would become a major regional department store chain.

- City of Paris department store at #177 during its final few years of operation, c.1895–1897.[52]

Phillips Block

[edit]

-

Entrance to Hamburger's department store (forerunner of May Co. California), located at the Phillips Block 1888–1908.

-

Phillips Block about 1900

-

Looking north on Spring St. from First Street, 1890s with view of the Phillips Block.

-

View north on Spring St. from First Street. Phillips Block visible in background, Harris & Frank's London Clothing Company at the SW corner of Franklin/Spring.

At the northwest corner of Franklin and Spring stood two buildings in succession, the Rocha Adobe, then the Phillips Block. The site now lies under the current course of Spring Street, which was straightened, i.e. realigned to run further west, in the 1920s.

- The Rocha Adobe (built 1820 as a residence for Antous Jose Rocha), 31–33 Spring Street (pre-1890 numbering), which from 1853–1884 served as the City Hall, and a building in the yard behind it served as the city and county jail.[53] It was demolished and in its place was built:

- Phillips Block (four-and-a-half stories, opened in 1888, Burgess J. Reeve, French Renaissance Revival architecture), 25–37 N. Spring St. (pre-1890 numbering) at the northwest corner of Franklin St., backing up to New High Street to the west. Owned by Pomona Valley rancher Louis Phillips, it cost $260,000. There was 120 feet (37 m) of frontage on Spring Street, 218 feet (66 m) on Franklin, and 121 feet (37 m) along New High Street. This building was the second four-story structure in Los Angeles. It was sometimes called Phillips Block No. 1 (there was a "Phillips Block No. 2" at 135–145 Los Angeles Street, on the west side between Market and First streets).[54] In July 1888, Asher Hamburger opened the Peoples Store here, later known as Hamburger's; it became the largest retail store in the Western United States. In 1908 it moved to 8th and Broadway, and in 1923 Hamburger sold it to May Co. and it became May Company California.[55] The Phillips Block was demolished in the mid-1920s to make way for the realigned Spring Street and today's City Hall.

Franklin to First

[edit]At the southwest corner of Franklin Street from 1894–1905 was Harris & Frank's London Clothing Co. with its landmark clock.[56][57] Harris & Frank went on to become a chain of junior department stores for men's clothing across the region.

East side of Spring south of Temple

[edit]Temple Block

[edit]

-

Looking south on Main St. towards Temple Block with Adolph Portugal dry goods store, mid-1870s

-

Further north on Main St., looking south towards Temple Block, mid-1870s

-

Temple Block c.1885. Courthouse clocktower visible immediately behind Temple Block. Main St. (l), Spring St. (r)

-

Spring St. side of Temple Block, sign for Cohn Bros. store, mid-1890s.

-

NE portion of Temple Block at SW corner of Temple (r) and Main (l), 1924

-

Eastern side of Temple Block, looking north along the west side of Main Street towards Temple St. (r), 1924

The triangular space where Spring and Main Streets came together at the south side of Temple Street was the site of Temple Block: actually a collection of different structures that occupied the block bounded by Spring, Main and Temple. The first or Old Temple Block built by Francisco (F. P. F.) Temple in 1856, was of adobe, two stories, facing north to Temple. This was incorporated into a later, expanded Temple Block in 1871, and then demolished. George P. McLain wrote that upon his arrival in the town in 1868, Temple Block had been the undisputed center of commerce and social life in the town. Even into the early 1880s, it was considered the city's most stately building. It housed many law offices, including those of Stephen M. White, Will D. Gould and Glassell, Chapman and Smith.[58] The block had a key role in the retail history of Los Angeles, as it was the first home to several upscale retailers who would become big names in the city: Desmond's (1870–1882)[59] and Jacoby Bros. (1879–1891).[60] It was also home to the Odd Fellows, the Fashion Saloon, the Temple and Workman Bank, Slotterbeck's gun shop, the Wells Fargo office. The northeast corner was home to Adolph Portugal's dry goods store (1874-1879?), Jacoby Bros. (1879–1891) and Cohn Bros. (1892–1897), in succession.[61][62]

In 1925-7 this block and other surrounding areas were demolished to make way for the current Los Angeles City Hall.

Along the south side of Temple Block was Market Street, a small street running between Spring and Main.

Clocktower Courthouse/Bullard Block

[edit]

-

Clocktower Courthouse viewed from Fort Hill (from the west)

-

View from Spring St. of Clocktower Courthouse (r), southside of Temple Block (l), United States Hotel (back)

-

Clocktower (Temple) Courthouse, Market and Theater

-

Clocktower Courthouse, view from Spring St. looking SE, with the Vienna Buffet on Court St. visible

-

Clocktower Courthouse

-

Bullard Block c.1900. It replaced the Clocktower Courthouse in 1895.

Taking up the small block immediately south of Temple Block between Market and Court streets, facing both Spring and Main streets, were two buildings in succession:

- Clock Tower Courthouse: Just south of Temple Block across tiny Market Street was a building known by many names including Temple Courthouse, Temple Market, Temple Theater, Old County Courthouse, etc. Also built by John Temple, in 1858, originally as a market (ground floor) and theater (upper floor). Demolished 1890s.[63][64] Served as a market and retail as well as the County Courthouse 1861-1891 until the Red Sand Courthouse was finished.[65] Topped by a rectangular tower with a clock on all four sides.[66][67] The Clock Tower Courthouse was demolished in 1895 and replaced by:

- Bullard Block, built in 1895-6, architects Morgan & Walls,[68] 154–160 N. Spring, NE corner of Court Street. Replaced the Clocktower Courthouse. Housed The Hub Clothing Co., a large department store for apparel. See also the photo below of "La Fiesta". Demolished 1925-6 to make way for current Los Angeles City Hall.[69]

Court south to First

[edit]

-

Vienna Buffet, which played a role in the city's LGBTQ history, seen sometime between 1891–1902

-

The "palatial" Jacoby Bros. store, 128–134 N. Spring Street, around 1896

- Court Street, a small street running between Spring and Main. At 12-14-16 Court Street (pre-1890 numbering). 112–116 Court St. (post 1890 numbering) was the Tivoli Theatre which opened and closed in 1890, lasting less than a year. From 1891 through 1902, the venue was the (New) Vienna Buffet, a restaurant with live music where scandal occurred, and gatherings of gay men including what were then called "she boys".[70] Then from 1902–c.1910, the site was the Cineograph Theatre, a vaudeville venue. From 1918–1925 it was marked the Chinese Theatre with the Sun Jung Wah Co. performing Chinese plays.[71]

- H. Jevne & Co. grocers were located at 38–40 (after 1890: 136-138) N. Spring (the older "Wilcox Block", also known as the Strelitz Block) from 1890-1896 before moving to the Wilcox Building when it opened at 2nd and Spring.[72][73]

- Jacoby Bros. dry goods store was located at 128–134 N. Spring St. from 1891-1900, and added the Jevne premises in 1896 (thus encompassing all of 128 through 138 N. Spring). The store moved to Broadway south of 3rd St. in 1900,[74][75] another signal that the upscale shopping district was moving southwest away from this area at that time.

First and Spring

[edit]-

View north on Spring St. from First Street. Los Angeles National Bank building in foreground, right. Larronde Block in foreground, left. Phillips Block visible in background. Note the electric streetcar to Grand Ave.

The image at above left looks south past the intersection of First and Spring sometime around 1900–1906. The spire of the Wilson Block is prominent on the left, as is the Nadeau Hotel on the right. In the foreground we can see the Los Angeles National Bank to the left and the Larronde Block to the right. From First to Second streets, Spring Street is still a busy shopping district, though Broadway is also just becoming popular for more upscale shopping. An electric streetcar heads to Griffin Avenue in Montecito Heights, on what would become Line 2 of the Los Angeles Railway. Today, this view would be of the 2009 LAPD Headquarters taking up the entire block on the left and on the right, the 1935 Los Angeles Times Building, and behind it, the 1948 Crawford Mirror Addition building.

Northwest corner of First and Spring

[edit]

-

Larronde Block in 1898. Photo by I. W. Taber[76]

-

Larronde Block, undated photo, probably 1910s

-

NW corner of 1st/Spring, 2020, an empty lot. Back right: County Courthouse (1972)

- Larronde Block, built in 1882 at a cost of $10,000,[77] 211 W. 1st St., also 101–105 N. Spring, two stories,[76] offices and retail shops, including:

- Mullen & Bluett, a major clothing store, 101–105 N. Spring,[78] from its founding in 1889 through 1910.[79]

- California State Building (completed 1931, opened 1932, architect John C. Austin, 1931, demolished 1976).[80]

- The lot is currently vacant

Northeast corner of First and Spring

[edit]

-

The east side of Spring Street, north of First, during the Fiesta de Los Angeles in 1903. The Bullard Block is in the distance at the top, center left.

-

Los Angeles National Bank Building

-

Equitable Savings Bank Building

-

North side of First Street between Spring and Main streets. Widney Block. c.1888

- Los Angeles National Bank Building (1887-1906), demolished and replaced by the

- Equitable Building (Equitable Savings Bank, 1906-1920s)[81]

First Street from Spring to Main

[edit]First Street east of Spring: Widney Block (i.e. Joseph Widney), built in 1883, along the north side. The main Olmsted & Wales bookstore was located in the block in the mid-1880s.

Southwest corner of First and Spring

[edit]

-

Nadeau Block housing the Nadeau Hotel (1882–1932)

-

L.A. Times Building, opened 1935, view in 2006.

- Nadeau Block or Nadeau Hotel, built 1881-2, demolished 1932, designed by architects Kysor & Morgan, located at the southwest corner of Spring and First streets. It was the first four-story building in the city.[82]

- This corner is now the site of the Los Angeles Times Building, opened 1935, part of the Times Mirror Square complex taking up the entire block between Spring, Broadway, First and Second streets, formerly the headquarters of the Los Angeles Times, currently vacant.

Southeast corner of First and Spring

[edit]

-

Wilson Block in 1920

-

The c.1927 two -story commercial block with the Security Pacific branch, seen from the City Hall tower

-

The 2009 L.A.P.D. Headquarters Building

Four buildings have stood here in succession:

- The George S. Wilson homestead[83]

- Wilson Block, sometimes called the city's first skyscraper.[84] Built 1886-8. Demolished around 1927.[85] The corner is now occupied by the Los Angeles Police Department Headquarters Building, completed in 2009.[86] The site is now home to:

- A replacement two-story retail building,[84] home to the "Equitable" branch of Security Pacific National Bank, then the Security Trust and Savings Bank. (the Equitable Building was across the street to the north).[87]

- Since 2009, the Police Headquarters Building taking up the entire block between First, Second, Spring and Main streets.

Second and Spring

[edit]Northwest corner of Second and Spring

[edit]

-

Bryson or Bryson-Bonebrake Block or Building erected 1886-8, photo 1905

-

The 1948 "Crawford Addition" building at Times Mirror Square, NW corner of 2nd & Spring, September 2020

- The Bryson Block, also known as the Bryson-Bonebrake Block or Bryson Bonebrake Building, northwest corner 2nd and Spring, constructed 1886-1888 for $224,000 on the site of a public school and an early city hall, as a 126-room bank and office building. Romanesque architecture. Two stories added 1902-1904. Demolished 1934. Architect Joseph Cather Newsom (Newsom & Newsom). Pacific Coast Architecture Database states it was "nothing short of amazing, displaying a riotous and eclectic amalgam of features". Built for mayor John Bryson and Major George H. Bonebrake, President of the Los Angeles National Bank and the State Loan & Trust Co.[88] Desmond's department store was located here from 1890 to 1900.[59]

It was replaced by the 1948 Crawford Addition building, part of the Times Mirror Square complex, currently vacant.

Northeast corner of Second and Spring

[edit]

-

1902 photo of the Burdick Block, on the NE corner of 2nd & Spring, built 1888; top floors added 1900.

-

L.A.P.D. Headquarters, opened 2012, NE corner of 2nd & Spring.

- Burdick Block, a.k.a. the Trust Building, 127 W. 2nd St., 1888 (J. N. Preston & Son), top stories added 1900 (John Parkinson). In 1910, refitted and rechristened the American Bank Building. Now site of the Los Angeles Police Department Headquarters which occupies the entire block from First to Second and from Spring to Main, completed 2009.[89][90]

Southwest corner of Second and Spring

[edit]-

View west on 2nd at Spring. Hollenbeck Block (left) when it was only two stories, note Coulter's store; 2nd City Hall (right), 1886

-

View south on Spring at 2nd, Hollenbeck Block when it was two stories, Coulter's store, 1886

-

Hollenbeck Block (1884-1933), SW corner of 2nd & Spring. c.1900-1905.

-

Historic Broadway station under construction, September 2020

- The Hollenbeck Block was located on the southwest corner of Spring and Second streets. It was built in 1884 by John Edward Hollenbeck and housed the Hollenbeck Hotel and, on the corner, from 1884–1898, Coulter's 6,000 sq ft (560 m2) store, which would become a leading Los Angeles department store. Built 1884, demolished in 1933. Architect Robert Brown Young.[91] Currently the construction site of Historic Broadway station, an underground station of the Los Angeles Metro Rail light rail subway.

Southeast corner of Second and Spring

[edit]

-

Wilcox Building, built 1895-6, photo from 1905

-

The Wilcox Building in September 2020

- Wilcox Building, built 1895-6, architects Pissis and Moore, five stories. All but the ground floor were removed in 1971 after damage from the 1971 Sylmar earthquake. It housed the larger of two branches of the H. Jevne & Co. gourmet grocery store, as well as the California Club until 1904, when the latter moved to Fourth and Hill streets. The Southwestern School of Law was on its top floors 1915–1924.[92]

200 block

[edit]

-

Music (Turnverein) Hall (l) and Los Angeles (Lyceum) Theatre (r). West side of Spring between 2nd and 3rd, 1895.

-

Looking north on Spring from 3rd St., 1905

-

Looking south on Spring between 2nd and 3rd, c.1905. In the background at center: towers of the Hotel Ramona. To its right, the Douglas Building, Woollacott Block, Anheuser restaurant, Hamilton Bros. shoe store block, and portion of the Turnverein Hall

-

Parmelee-Dohrmann store at the Workman Block, 232–234 S. Spring, photo c.1900-1906

On the west side:

- #217 (pre-1890 numbering: #119), the Parisian Cloak and Suit Co., 1888–1892; then 221 S. Spring until 1899. One of the city's prominent retailers of women's clothing during that era.

Two theatres together called the Perry Buildings:

- at #225–9 was the Lyceum Theatre, opened in 1888 as the Los Angeles Theatre (not to be confused with the Los Angeles Theatre on Broadway, still standing). From 1903-1911 this venue operated as the Orpheum Theatre. As the Orpheum Circuit was a chain and changed venues several times, the "Orpheum Theatre" in Los Angeles was first at the Grand Opera House venue on Main Street, then at this venue, and finally at the venue now known as the Palace Theatre on Broadway. [93]

- at #231–5 was the Turnverein Hall (opened 1879), a theatre, renamed the Music Hall in 1894, Elks Hall in the early 1900s and Lyceum Hall in 1915. Demolished.[94]

- #237–241, Hamilton Bros. block, Hamilton Bros. (later Hamilton & Baker, C. H. Baker)[95] shoe store at #239.[96]

- #243, Anheuser-Busch saloon, later known as The Anheuser Restaurant.[97]

- #245–7, Woollacott Block[96]

On the east side:

- Stowell Block at #224–228. In 1894 the Los Angeles Athletic Club was located here from 1893 until 1895.[98][99]

- Workman Block at #230–234. 232–234 were home to Parmelee-Dohrmann from 1899 through 1906. It was the city's premier store for china, crystal and silver, as well as — at that time — selling appliances like stoves and refrigerators. In 1906, the store moved to the 5th and Broadway area.[100]

Third and Spring

[edit]

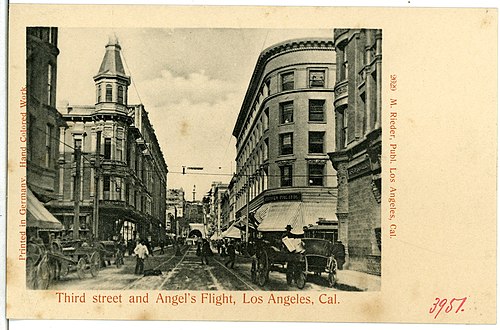

-

1903, looking west on Third past Spring: Desmond's store located 1900–1906 in the turreted Ramona Block on the SW corner, left, and Southern Pacific Railroad office in the Douglas Building, still standing today, on the NW corner, right. At far background, Angel's Flight at 3rd and Hill.

-

Douglas Building (1899– ), NW corner

-

Metropolitan Barber Shop, 215 W. 3rd (demolished)

-

Stimson Block, NE corner (1893–1963)

-

Stimson Block in the mid-20th century

-

Hotel Ramona, SW corner (1885–1903)

-

Washington Bldg. (1912) at SW corner

-

Lankershim Building (1896–1959), SE corner

-

Ronald Reagan State Office Bldg. occupies the SE corner of 3rd & Spring today. Spring runs along its right side; this view looks south on Main St.

Northwest corner of Third and Spring

[edit]- Hammel and Denker Block (opened 1890, demolished 1899);[101] Henry Hammel and Andrew H. Denker were business partners in hotels and ranching. Thomas Douglas Stimson bought it in 1893, thus owning two buildings at this intersection: this one and the Stimson Block (see below). Leading dry goods retailer Frank, Grey & Co. opened here in 1890[102] and the store was later taken bought by, and turned into a branch of J. M. Hale.[103]

- The Hammel & Denker Block was demolished and replaced by the Douglas Block in 1899 and still standing, now condos.[104]

- To the west of the Douglas Block stood the Metropolitan Barber Shop, originally at 214 W. 3rd, in 1908 it moved to 215-9 W. 3rd. The Los Angeles Herald claimed it to be the largest barber shop in the world at that time and the most expensive ever constructed, with 30 chairs, chandeliers and mahogany furnishings.[105]

Northeast corner of Third and Spring

[edit]- Stimson Block or Stimson Building, built 1893, architect Carroll H. Brown (also designed the Stimson House), demolished 1963. The city's tallest building when it opened. Built for lumber magnate Thomas Douglas Stimson. Now site of a parking lot.[106]

Southwest corner of Third and Spring

[edit]- The Callaghan Block or Ramona Block housing the Hotel Ramona, (1885, Burgess J. Reeve, classic bay-windowed style).[107] Demolished in 1903 and replaced by the Washington Building, built 1912, Parkinson and Bergstrom, still standing.[108][109]

Southeast corner of Third and Spring

[edit]- Site of the Lankershim Building (1896-7, Robert Brown Young, demolished 1959).[110] Now the site of the Ronald Reagan State Building.

See also

[edit]- List of Registered Historic Places in Los Angeles

- International Savings & Exchange Bank Building, (1907) at 227 N. Spring Street (now demolished)

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c Tim Sitton (Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History) (July 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form: Spring Street Financial District" (PDF). Los Angeles Conservancy web site.

- ^ a b c d e f Rasmussen, Cecilia (June 11, 2000). "Wall Street of the West Had Its Peaks, Crashes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ^ "The long and the short of the Southland's street names". Los Angeles Times. December 10, 2006.

- ^ "North Spring Street, Los Angeles", Google Maps, retrieved October 23, 2020

- ^ 1868 map of Zanja Madre, Los Angeles

- ^ a b "Image 1 of Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, California.", via Library of Congress

- ^ Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, California. Sanborn Map Company, 1920

- ^ "Spring Street Financial District Walking Tour". Los Angeles Conservancy.

- ^ South Spring Street Los Angeles California, Thomas Edison

- ^ Tim Sitton (Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History) (July 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form: Spring Street Financial District, at page 8" (PDF). Los Angeles Conservancy web site. ("”The Continental Building (first known as the Braly Building) was considered the first ‘skyscraper’ in Los Angeles.”)

- ^ a b c d e f "Millions in Skyscrapers: Staggering Sum Going into Metropolitan Blocks; Downtown Sky Line Daily Grows More Imposing;". Los Angeles Times. April 15, 1911.

- ^ a b Michelle V. Rafter (November 5, 1997). "Spring Hopes Eternal: Visionaries think the blighted downtown L.A. Street can be turned into a center for entertainment and high-tech firms. Skeptics cite past failures". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c d e f John Dreyfuss (May 14, 1982). "Spring Street: On the Road to Respectability". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Reed Johnson (April 19, 2001). "L.A. at Large: Soul Searching on Spring Street; As developers lure wealthier residents downtown, the historic area's gritty and bohemian past collides with a glossy future". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c Jack Smith (May 6, 1985). "Cultural and architectural richness distinguish the old Spring Street financial district". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Melinda Fulmer (December 1, 1998). "Rental Units Are Proposed for Downtown; Housing: Gilmore Associates wants to turn a mostly vacant stretch of 4th Street into 250 market-rate apartments". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Robert A. Jones (December 6, 1998). "The Distant Sound of a Miracle". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Karen Lindell (March 4, 2001). "As more of L.A.'s historical buildings are converted to residential units, people are leaving the sprawl of suburbia for the diverse and vibrant heart of downtown". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jason Mandell (November 17, 2003). "Old Bank Draws Five Years of Interest: Gilmore's Project Has Made Major Strides, but Much Work Remains". LA Downtown News Online. Archived from the original on December 3, 2003.

- ^ "Downtown L.A. Lofts". LA Loft.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007.

- ^ "About Spring Arts Tower". Spring Arts Tower.

- ^ The Rowan Building History – ROWAN LOFTS – Los Angeles Downtown

- ^ "Rowan Building". Killefer Flammang Architects.

- ^ a b c d e f Terence M. Green (June 22, 1975). "Alexandria Hotel Changes Owners". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "The Alexandria". The Alexandria. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011.

- ^ a b Ray Hebert (August 27, 1982). "Arts to Flourish in Former Bank: Noted Structure on L.A.'s Spring Street Will Be Converted". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Sylvie Drake (September 25, 1986). "Stage Watch: Theatre Center Survival a Cliffhanger". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ The New Latc

- ^ USC Geography : LA Walking Tour : Historic Core : Arcade Building

- ^ "Arcade Building to Be Turned Into Loft-Style Apartments". Los Angeles Times. April 9, 2002.

- ^ Ray Hebert (July 8, 1985). "No Tall Buildings: Aesthetics, Not Quakes, Kept Lid On". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ David M. Kinchen (May 12, 1985). "Developers Bet on Comeback for Spring Street". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Los Angeles Stock Exchange: Finance; Research and Discover; Production". Public Art in Los Angeles.

- ^ Ray Hebert (July 6, 1981). "Spring Street Gem Starts a Renewal: Former Office Edifice in Financial District Converting into Housing". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Bill Boyarsky (June 20, 1990). "They're the Prisoners of Spring Street". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ http://www.downtownnews.com/articles/2004/09/20/development/estate04.txt [bare URL plain text file]

- ^ "Nonprofit Center". MALDEF.

- ^ "To Occupy Fine New Building: Union Oil Company Is Moving". Los Angeles Times. July 23, 1923.

- ^ Dorothy Townsend (March 23, 1972). "Southwestern University: a Shirtsleeve Law School". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "SB Properties". laloftrental.com. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^

"650 South Spring Building". Emporis. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Vincent, Roger (October 15, 2014) "Historic downtown Los Angeles high-rise sold to Canadian investors" Los Angeles Times

- ^ Los Angeles Department of City Planning (July 31, 2014). "Historic – Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing: City Declared Monuments" (PDF). City of Los Angeles. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ [Albert Walker and Percy Eisen www.ladowntownnews.com/news/spring-street-housing-tower-sells-for-43-million/article_becddd1c-5589-11e4-913b-577b42b00c80.html "Spring Street Housing Tower Sells for $43 Million"]. Downtown News. October 16, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Nine Acres Space in Robinson Store". Los Angeles Evening Express. May 30, 1914.

- ^ a b "Wreckers Put Hammer to Old Health Building". Los Angeles Times. December 30, 1954.

- ^ "City Improvements". Los Angeles Herald. March 4, 1883. p. 3.

The improvements in the Jones Block, opposite the Court House…are also part of the improvements

- ^ "Mrs. Doria Jones' new block on Spring street". Los Angeles Times. Newspapers.com. July 29, 1882. p. 3. Retrieved November 6, 2024.

- ^ Sanborn 1894 map of Los Angeles, plate 10 (east), via Library of Congress

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

s1888-18was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "City of Paris 1895 177 N Spring". Los Angeles Times. September 11, 1895. p. 4 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rocha Adobe", Water and Power Associates

- ^ Stern, Norton B. "Louis Phillips of the Pomona Valley". Historical Society of Southern California: 184.

- ^ "Architect B. J. Reeve". San Francisco Examiner. August 14, 1887. p. 19. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- ^ "Advertisement by London Clothing Co., Harris & Frank, proprietors". Los Angeles Herald. February 17, 1894. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Block 10 as sown on Sanborn Fire Map, 1894

- ^ Israel, S. A. (January 3, 1926). "Historic Temple Block Surrenders to Progress after Seventy Years". Los Angeles Times. p. 71.

- ^ a b "Desmond's in Seventy-Sixth Year", Los Angeles Times, 21 Oct 1937, Page 8

- ^ "Concentrating: The Growth of a Business and a Great Bazaar: A Grand Rally of Wholesale and Retail: Outposts and Pickets Under One Large Roof: The Jacoby Bros. Occupy Their New and Magnificent Building and Receive the Congratulations of Their Many Friends". Los Angeles Times. November 14, 1891. p. 3.

- ^ Ad for Cohn Bros., [Los Angeles Herald]] May 14, 1892, p. 8

- ^ Ad for Cohn Bros. in Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1897

- ^ "Buildings and Lands. The July Permits Break the Record. The Remarkable Gains over Last Year's List". Los Angeles Express. August 3, 1895. p. 5.

- ^ "Bullard Block", Los Angeles Water & Power

- ^ https://waterandpower.org/museum/Early_LA_Buildings%20(1800s)_Page_1.html#Temple_Block

- ^ https://waterandpower.org/museum/Early_LA_Buildings%20(1800s)_Page_1.html#Temple_Block

- ^ "U.S. Courthouse, Los Angeles, CA". General Services Administration. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- ^ https://www.newspapers.com/clip/57340846/bullard-block-the-hub-opening/

- ^ "Bullard Block wrecking begun by 100 workmen". Los Angeles Evening Express. December 22, 1925. p. 1.

- ^ de Simone, Tom (2011). Lavender Los Angeles. Arcadia Publishing. p. 24.

- ^ "Cineograph", Los Angeles Theatres

- ^ Grace, Roger (February 15, 2007). "Reminiscing: H. Jevne offers free home delivery". Metropolitan News-Enterprise.

- ^ "Jevne gricery store #2", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ "Grand opening: Jacoby Brothers' outfitting store on Broadway". Los Angeles Times. March 4, 1900. p. 35.

- ^ "Los Angeles Herald 22 August 1899 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu.

- ^ a b "Larronde Building", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ "Building Improvements". Los Angeles Herald. February 22, 1882. p. 3.

- ^ "Mullen & Bluett Clothing Co.", Los Angeles City Directory, 1905

- ^ "Ability wins its own reward: Interesting sketch of the success of a pioneer establishment conducted under able and efficient management: Largest clothing and furnishings goods house in Southern California". Los Angeles Herald. January 27, 1910. p. 8. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ https://calisphere.org/item/5459a5690c02f89dcc7f274e66e13d7e/

- ^ "Los Angeles National Bank" and "Equitable Savings Bank", Water and Power Associated

- ^ "Nadeau Hotel", PCAD

- ^ "Rites for Native of City Today". Los Angeles Times. May 6, 1927.

- ^ a b "New Block Razed for Structure", Los Angeles Times, August 28, 1927

- ^ "Wilson Block", Water and Power Associates

- ^ "Los Angeles Police Department Headquarters #2", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ Ad for the Security Trust and Savings Bank in the Los Angeles Times, January 16, 1928

- ^ "Bryson-Bonebrake Building, Downtown, Los Angeles, CA (1886-1888) demolished". Pacific Coast Architecture Database. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "Burdick Block", Romanesque Revival Los Angeles

- ^ "Burdick Block", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ "Hollenbeck Block", Calisphere, University of California

- ^ "Wilcox Building #2". Pacific Coast Architecture Database. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ https://losangelestheatres.blogspot.com/2019/03/lyceum-theatre.html

- ^ https://losangelestheatres.blogspot.com/2019/02/lyceum-hall.html

- ^ "Hamilton & Baker, 239 S. Spring St., dissolved partnership. C. H. Baker will continue the business". Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. February 26, 1904. p. 6. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Sanborn 1894 map of Los Angeles, vol. 1, plate 8

- ^ "Memoranda". Los Angeles Herald. August 19, 1893. p. 8. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Charles F. Lummis (ed.), "Los Angeles Athletic Club," The Land of Sunshine [Los Angeles], vol. 5, no. 3 (Aug. 1896). pg. 134.

- ^ Sanborn map of Los Angeles, 1894, vol. 1 plate 9 via Library of Congress]

- ^ "Advertisement for "China Hall"". Los Angeles Times. June 17, 1899.

- ^ Sanborn 1894 map of Los Angeles, plate 8 (right), via Library of Congress

- ^ "Grand Opening". Los Angeles Herald. October 5, 1890. p. 5. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ "Advertisement for Hale's branch at corner of Third and Spring, "Frank, Grey & Co.'s old stand"". The Los Angeles Times. March 14, 1893. p. 6. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ "Douglas Building", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ "Metropolitan Barber Shop". Los Angeles Herald. December 20, 1908. p. 32.

- ^ "Stimson Building", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ "Third and Spring", Romanesque Revival Downtown

- ^ "Washington Building", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ "Hotel Ramona", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ "Lankershim Building", Pacific Coast Architecture Database

![Larronde Block in 1898. Photo by I. W. Taber[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Larronde_Block_1898.png/474px-Larronde_Block_1898.png)