Tercio

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (September 2023) |

| Spanish Tercios | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1 January 1534 (de jure establishment) |

| Country | Spain See details

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Close combat Hand-to-hand combat Hedgehog defence Pike square Raiding Volley fire |

| Part of | Spanish Armed Forces |

| Patron | Ferdinand II Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor Philip II of Spain Philip III of Spain Philip IV of Spain Charles II of Spain Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Motto(s) | Spain my nature, Italy my fortune, Flanders my grave[citation needed] |

| Equipment | Arquebuses, muskets, and pikes |

| Commanders | |

| Gran Capitán | Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba |

| Comandante | John of Austria[1] Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy[2] |

| Insignia | |

| War flag |  |

A tercio (pronounced [ˈteɾθjo]), Spanish for "[a] third") was a military unit of the Spanish Army during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and Habsburg Spain in the early modern period. They were the elite military units of the Spanish monarchy and the essential pieces of the powerful land forces of the Spanish Empire, sometimes also fighting with the navy.

The Spanish tercios were one of the finest professional infantries in the world due to the effectiveness of their battlefield formations and were a crucial step in the formation of modern European armies, made up of professional volunteers, instead of levies raised for a campaign or hired mercenaries typically used by other European countries of the time.

The internal administrative organization of the tercios and their battlefield formations and tactics, grew out of the innovations of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba during the conquest of Granada and the Italian Wars in the 1490s and 1500s, being among the first to effectively mix pikes and firearms (arquebuses). The tercios marked a rebirth of battlefield infantry comparable to the Macedonian phalanxes and the Roman legions.[3] Such formations distinguished themselves in famous battles such as the Battle of Bicocca (1522) and the Battle of Pavia (1525). Following their formal establishment in 1534, the reputation of the tercio was built upon their effective training and high proportion of "old soldiers" (veteranos), in conjunction with the particular elan imparted by the lower nobility who commanded them. The tercios were finally replaced by regiments in the early eighteenth century.

From 1920, the name of tercio was given to the formations of the newly created Spanish Legion; professional units then created to fight colonial wars in North Africa, similar to the French Foreign Legion. These formations are actually regiments bearing the name of tercio as an honorary title.

History

[edit]

During the Granada War (1482–1491), the soldiers of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain were divided into three classes: pikemen (modelled after the Swiss), swordsmen with shields, and crossbowmen supplemented with an early firearm the arquebus.[citation needed] As shields disappeared and firearms replaced crossbows, Spain won victory after victory in Italy against powerful French armies, beginning under the leadership of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba (1453–1515), nicknamed El Gran Capitán (The Great Captain).[4] The military organizational and tactical changes made by Córdoba to the armies of Spanish monarchs are seen as the precursors of the tercios and their methods of warfare.[citation needed] The combat effectiveness of the Spanish pike and shot armies pioneered by Córdoba was based on an armament system that effectively united the pike with the compact firepower of the arquebus. An advantage of the Spanish pike and shot formation over the Swiss compact frame that had inspired it was in its ability to divide into mobile units and even individual melee without the loss of cohesion.[citation needed]

Initially, the term tercio denoted not a combat unit, but an administrative unit under a general staff, commanding garrisons throughout Italy for battles on various distant fronts.[5] This peculiar character was maintained when it mobilized to fight the Protestant rebels in Flanders. Command of a tercio and its companies of soldiers was granted directly by the king, and companies could easily be added or removed and moved to and from other tercios.[citation needed] By the middle of the 17th century, the tercios began to be raised by nobles at their own expense, patrons who appointed the captains and were effective owners of the units, as in other contemporaneous European armies.

From the conquest of Granada in 1492 to the campaigns of El Gran Capitán in the kingdom of Naples in 1495, three ordinances laid the foundations of Spanish military administration. In 1503, the Great Ordinance reflected the adoption of the long pike and the distribution of infantry in specialized companies.[citation needed] In 1534, the first official tercio was created, that of Lombardy, and a year later it helped in the conquest of the Duchy of Milan. The tercios of Naples and Sicily were created in 1536, thanks to the Genoa ordinance of Charles V.[6][7]

At the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547, the imperial troops of Charles V defeated a league of Protestant princes in Germany, thanks mainly to the action of the Spanish tercios.[citation needed] In 1557, the Spanish army completely defeated the French at the Battle of San Quentin, and again in 1558 at Gravelines, which led to a peace greatly favoring Spain. In all these battles, the effectiveness of the tercio units stood out.

The origin of the term tercio is doubtful. Some historians believe the name was inspired by the tercía, a Roman Legion of Hispania.[citation needed] Some[who?] think that it designated the threefold division of the Spanish forces in Italy. Others[who?] trace it to the three types of combatants (pikemen, harquebusiers, musketeers). According to an ordinance for "people of war" of 1497, where the formation of the infantry is changed into three parts.

The pawns [the infantry] were divided into three parts. The one tercio with spears, as the Germans brought them, which they called pikes; and the other had the name of shields [people of swords]; and the other, of crossbowmen and spit bearers. [later replaced by arquebusiers].

Yet others[who?] derive the name from the three thousand men mustered in the first units. This last explanation is supported by the field master Sancho de Londoño in a report to the Duke of Alba in the 16th century:

The tercios, although they were instituted in imitation of the [Roman] legions, in few things can be compared to them, that the number is half, and although formerly there were three thousand soldiers, for which they were called tercios and not legions, already it is said like this even if they do not have more than a thousand men.[8]

Composition and characteristics

[edit]

Although other powers adopted the battle formations and tactics perfected by the tercios, their armies fell short of the fearsome reputation of the Spanish army, which possessed a core of experienced professional soldiers.[9] This army was further supplemented by "an army of different nations", a reference to the varied origins of the troops from the German and Italian states and the Spanish Netherlands and smaller units from other countries such as Ireland. In 1621, for example, of the 47 military units of the Spanish army, counting together the larger Spanish, Spanish Netherlands and Italian tercios, and the much smaller German, Burgundian and Irish regiments,[10] Only seven were manned by troops of Spanish origin.[11] Such international musters were characteristic of European warfare before the levies of the Napoleonic Wars. However, the core Spanish troops were Spanish subjects, admired for their cohesiveness, superior discipline and overall professionalism.[12]

Organization

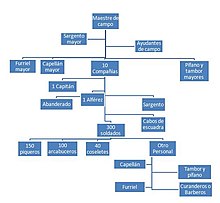

[edit]Initially, each tercio that served in Italy and the Spanish Netherlands was organized into:

- 10 companies of 300 soldiers each led by captains, in which

- 8 were pikemen's companies and

- 2 were of arquebusier companies

The companies were later reduced to 250 men and the ratio of arquebusiers (later musketmen) to pikemen steadily increased.

During the early actions in the Netherlands, the tercios were reorganized into three coronelias ("colonelcies"), led by coronels ("colonels") each composed of a headquarters unit and four companies each (the predecessor of today's battalions), but as a whole continued to be subdivided into the same 10 companies of 250 personnel each: two of arquebusiers and 8 of pikemen. Colonels were also of royal appointment.

Staff

[edit]

- Maestre de Campo – colonel

- Coronel – colonel/lieutenant colonel

- Sargento mayor – major

- Furriel mayor – quartermaster

- Capellán mayor – chaplain

- Pifano mayor – fife major

- Tambor mayor – drum major

Company

[edit]- 1 Capitán – captain

- 1 Alférez – lieutenant

- Abanderado – standard-bearer

- Sargento – sergeant

- Capellán – chaplain

- Furriel – quartermaster

- Tambor – drummer

- Pifano – fifer

- Barbero – barber surgeon

- Cabos de escuadra – corporals

- 150 piqueros – pikemen

- 100 arcabuceros – arquebusiers (later musketeers)

- 40 coseletes – sword-and-buckler men

Leadership of the tercio

[edit]

Similar to military organization today, a tercio was led by a maestre de campo (commanding officer) appointed by the king, with a guard of eight halberdiers. Assisting the maestre was the sergeant major and a furir major in charge of logistics and armaments. Companies were led by a captain (also royally appointed), with an ensign in charge of the company color.

The company non-commissioned officers were sergeants, furrieles (furirs) and corporals. A sergeant served as second-in-command of a company and transmitted the captain's orders; furrieles provided weapons and munitions, as well as additional manpower; corporals led groups of 25 (similar to today's platoons), watching for disorder in the unit.

Each company had corps of drums made up of drummers and fifers, sounding duty calls in battle, with the drum major and fife major being provided by the tercio headquarters.

The tercio staff included a medical component (made up of a professional medic, a barber, and surgeons), chaplains and preachers, and a judicial unit, plus military constables enforcing order. They all reported directly to the maestre de campo.

Battle formations

[edit]

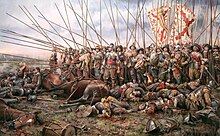

Within a tercio's squares, ranks of pikemen assembled into a hollow pike square (cuadro) containing swordsmen – typically with short sword, buckler, and javelins. As firearms rose in prominence, the swordsmen were phased out. The arquebusiers (later, musketeers) were usually split up in several mobile groups called "sleeves" (mangas), typically deployed with one manga at each corner of the cuadro.[citation needed] By virtue of this combined-arms approach, the formation simultaneously enjoyed the staying power of its pike-armed infantry, the ranged firepower of its arquebusiers, and the striking power of its sword-and-buckler men. However, as the formation matured in practice, the number of swordsmen was reduced and then eliminated and the ratio of gunmen to pikemen increased over time. In addition to its defensive ability to repulse cavalry and other forces along its front, the long-range fire of its arquebusiers could be easily shifted to the flanks, making it versatile in both attack and defense.

Groups of squares were typically arrayed in dragon-toothed formation, staggered, with the leading edge of one unit level with the trailing edge of the preceding, similar to hedgehog defence. This enabled enfilade lines of fire and somewhat defiladed the army units themselves. Odd units stood forward, alternating with even units stepped back, providing gaps for an unwary enemy to enter and expose its flanks to raking crossfire from the guns of three separate squares. Tercio companies also conducted particular operations independently of the main formations.

Tercios and the Spanish Empire

[edit]Tercios were deployed all over Europe under the Habsburg rulers. They were made up of volunteers and built up around a core of professional soldiers and were highly trained. Sometimes later tercios did not stick to the all-volunteer model of the regular Imperial Spanish army – when the Habsburg king Philip II found himself in need of more troops, he raised a tercio of Catalan criminals to fight in Flanders,[13] a trend he continued with mostly Catalan criminals for the rest of his reign.[14] A large proportion of the Spanish army (which by the later half of the 16th century was entirely composed of tercio units: The Tercio of Savoy and the Tercio of Sicily were deployed in the Netherlands to quell the increasingly difficult rebellion against the Habsburgs. Ironically, many units of the Spanish tercios became part of the problem rather than the solution when the time came to pay them: with the Spanish coffers depleted by constant warfare, unpaid units often mutinied. For example, in April 1576, just after winning a major victory,[specify] unpaid tercios mutinied and occupied the friendly town of Antwerp, in the so-called Spanish Fury at Antwerp, and sacked it for three days.[15] Completely reliant on his troops, the Spanish commander could only comply.[16]

Specialized tercios

[edit]On 24 February 1537, the Tercio de Galeras (Tercio of Galleys) was created. Today, the Real Infantería de Marina (Spanish Marine Infantry) consider themselves successors of the legacy and heritage of the Galleys Tercios making it the oldest currently operating marines unit in the world. There were other units of naval tercios such as Tercio Viejo de Armada (Old Navy Tercio) or Tercio Fijo de la Mar de Nápoles (Permanent Sea Tercio of Naples). Such specialized units were needed for the protracted war with the Ottoman Empire over the entire Mediterranean.

Naming conventions

[edit]Most tercios were named according to the place where they were raised or first deployed: thus they were Tercio de Sicilia, de Lombardía, de Nápoles (Tercio of Sicily, of Lombardy, of Naples) and so on. Other tercios were named for their commanding officer, such as Tercio de Moncada for its commander Miguel de Moncada (whose most famous soldier was Miguel de Cervantes). Some tercios were named by their main function, such as Galeras or Viejo de Armada.

Colours

[edit]-

The Cross of Burgundy was adopted as the symbol of the Tercios and the Spanish Empire.

-

Tercio de la Liga (1571)

-

Unknown Tercio flag (appears near commander Ambrogio Spinola in the painting "The Surrender of Breda" of Diego Velázquez) (1621)

-

Tercio de Alburquerque (1643)

-

Tercio Morados Viejos (1670)

-

Tercio Amarillos Viejos (1680)

The Portuguese terços

[edit]

Portugal adopted the Spanish model of tercio in the 16th century, calling it terço. In 1578, under the reorganization of the Portuguese Army conducted by King Sebastian, four terços were established: the Terço of Lisbon, the Terço of Estremadura, the Terço of Alentejo, and the Terço of Algarve. Each had about 2,000 men, formed into eight companies.

The infantry of the army organized for the expedition to Morocco in 1578 was made up of these four terços together with the Terço of the Adventurers (totally made up of young nobles), three mercenary terços (the German, the Italian, and the Castilian), and a unit of elite sharpshooters of the Portuguese garrison of Tangier. This was the Portuguese force which fought the Battle of Alcácer Quibir.

While united with the Spanish Crown, from 1580 to 1640, Portugal kept the organization of terços, although the Army had declined. Several Spanish tercios were sent to Portugal; the principal of them, the Spanish infantry Tercio of the City of Lisbon, occupied the main fortresses of the Portuguese capital. The Terço of the Navy of the Crown of Portugal, the ancestor of the modern Portuguese Marines, was created in this period.

After the restoration of Portuguese sovereignty in 1640, the Army was reorganized by King John IV of Portugal. The terços remained the basic units of the Portuguese infantry. Two types of terços were organized: the paid terços (first line permanent units) and the auxiliary terços (second line militia units). Portugal won the Restoration War with these terços.

At the end of the 17th century, the terços were already organized as modern regiments. However, the first line terços were only transformed into regiments in 1707, during the War of the Spanish Succession – after the Spanish tercios were transformed into regiments in 1704. The second line terços were only transformed into militia regiments in 1796. Some of the old terços are direct ancestors of modern regiments of the Portuguese Army.

Evolution and replacement

[edit]

The first real challenge to the dominance of the Spanish tercios on the open battlefield came at the Battle of Nieuwpoort (1600). The victor of Nieuwpoort, the Dutch stadtholder Maurice, Prince of Orange, believed he could improve on the tercio by combining its methods with the organisation of the Roman legion. These shallower linear formations brought a greater proportion of available guns to bear on the enemy simultaneously. The result was that the tercio squares at Nieuwpoort were badly damaged by the weight of Dutch firepower. Yet the Spanish army very nearly succeeded in spite of internal dissensions that had compromised its regular command. The Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) in the Low Countries continued to be characterized by sieges of cities and forts, while field battles were of secondary importance. Maurice's reforms did not lead to a revolution in warfare, but he had created an army that could meet the tercios' battle formations on an even basis and that pointed the way to future developments. During the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) tercio style battle formations of the Holy Roman Empire suffered major defeats at the hands of more linear formations created and led by the Swedish soldier-king Gustavus Adolphus. However, the tried-and-true tactics and professionalism of the Spanish tercios played a decisive role in defeating the Swedish army at the Battle of Nördlingen.[17]

Throughout its history, the tercios' composition and battlefield formations and tactics evolved to meet new challenges. The classic pike and shot square formations fielded by the Spanish tercios and good cavalry support continued to win major battles in the 17th century, such as Wimpfen (1622), Fleurus (1622), Breda (1624), Nördlingen (1634), Thionville (1639), and Honnecourt (1641). It was not until Rocroi (1643) that the Spanish tercio's reputation of invincibility in open battle was shattered. Still, the Rocroi defeat was precipitated by the collapse of the supporting cavalry rather than the failure of the tercios' infantry. Even then, the tercios continued to win battles immediately after Rocroi, such as at Tuttlingen (1643) and Valenciennes (1656), although their composition and battlefield style had continued to evolve. In this period steady improvements in firearms and field artillery were increasingly favoring the linear style. By the late 17th century the tercios had adopted so much of the linear style that their battlefield formations and tactics often had little resemblance to the battle formations and tactics a century earlier.

Royal Military and Mathematics Academy of Brussels

[edit]In 1675 the first modern Royal Military and Mathematics Academy of Brussels was founded in Brussels by its sole-director Don Sebastián Fernández de Medrano, at the request of the Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands, Carlos de Aragón de Gurrea, 9th Duke of Villahermosa, in order to correct the shortage of artillerymen and engineers from the Spanish Tercios.[18]

This Royal Military and Mathematics Academy in Flanders was renowned for the diverse origin of its officer cadets, for the innovative features of its plan of studies produced by Sebastián Fernández de Medrano, the theoretical and practical basis of its learning process apart from the relevant assignments given to its officer cadets who were also known as the “Great Masters of War” coined by the treatise writer, Count of Clonard. It was created in Brussels to train the most distinguished officers in the peninsula in the Art of War.[19]

The Royal Military Academy of Flanders was an educational institution to train military engineers with various fields of education such as arithmetic, geometry, artillery, fortification, algebra, cosmography, astronomy, navigation, etc.[20]

Transformation of the Spanish Tercio

[edit]In 1704, the regular Spanish tercios were transformed into regiments and the pikeman as an infantry type was dropped. Those of the reserves and the militia would later be transformed into similar organisations.

Famous battles

[edit]Victories

[edit]Pre-official nomenclature

[edit]- Cerignola (1503)

- Garigliano (1503)

- Mers-el-Kébir (1505)

- Oran (1509)

- La Motta (1513)

- Noáin (1521)

Official nomenclature

[edit]- Tunis (1535)

- Serravalle (1544)

- Muhlberg (1547)

- St. Quentin (1557)

- Gravelines (1558)

- Malta (1565)

- Lannoy (1566)

- Dahlen (1566)

- Oosterweel (1567)

- Jemmingen (1568)

- Jodoigne (1568)

- Lepanto (1571)

- Mons (1572)

- Goes (1572)

- Haarlem (1573)

- Mook (1574)

- Valkenburg (1574)

- Schoonhoven (1575)

- Oudewater (1575)

- Zierikzee (1576)

- Gembloux (1578)

- Borgerhout (1579)

- Maastricht (1579)

- Alcantara (1580)

- Noordhorn (1581)

- Terceira (1582)

- Eindhoven (1583)

- Steenbergen (1583)

- Empel (1585)

- Antwerp (1585)

- Neuss (1586)

- Sluis (1587)

- Rheinberg (1590)

- Paris (1590)

- Craon (1592)

- Doullens and Groenlo (1595)

- Lippe (1595)

- Calais (1596)

- Groenlo (1606)

- Oppenheim (1620)

- Bacharach (1620)

- Jülich (1621)

- Wimpfen (1622)

- Fleurus (1622)

- Heidelberg (1622)

- Höchst (1622)

- Mannheim (1622)

- Breda (1625)

- Cádiz (1625)

- Genoa (1625)

- Salvador de Bahia (1625)

- Nordlingen (1634)

- Leuven (1635)

- Somme (1636)

- Venlo (1637)

- Kallo (1638)

- Thionville (1639)

- Honnecourt (1642)

- Tuttlingen (1643)

- Valenciennes (1656)

Defeats

[edit]- Ravenna (1512)

- Castelnuovo (1539)

- Algiers (1541)

- Ceresole (1544)

- Leiden (1574)

- Rijmenam (1578)

- Alcácer Quibir (1578)

- Ivry (1590)

- Caudebec (1592)

- Siege of Coevorden

- Morlaix (1594)

- Fort Crozon (1594)

- Fontaine-française (1595)

- Amiens (1597)

- Turnhout (1597)

- Zaltbommel (1599)

- Nieuwpoort (1600)

- Kinsale (1601)

- Sluis (1604)

- Les Avins (1635)

- Tornavento (1636)

- Schenkenschans (1636)

- Turin (1640)

- Montjuïc (1641)

- Lleida (1642)

- Rocroi (1643)

- Lens (1648)

- Arras (1654)

- The Dunes (1658)

- The Lines of Elvas (1659)

- Ameixial (1663)

- Castelo Rodrigo (1664)

- Montes Claros (1665)

See also

[edit]- Pike and shot

- Musketeer

- Captain Alatriste

- Military history

- Spanish Navy Marines units are called tercios

- The units of the modern Spanish Legion are also called tercios.

References

[edit]- ^ "No. 62738". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 August 2019. p. 14447.

- ^ "No. 62738". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 August 2019. p. 14447.

- ^ "... y, con el Gran Capitán, la aparición ni más ni menos que del tercio español, de algo que equivale en la historia universal al nacimiento de la falange Macedonia o de la legión romana." Fernand Braudel, El Mediterráneo y el mundo mediterráneo en la época de Felipe II, tomo II, p. 28, FCE, 1.976.

- ^ López, Ignacio J.N (20 July 2012). The Spanish Tercios 1536-1704. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9781849087940.

- ^ De Mesa Gallego 2009, p. 195.

- ^ Estes, Kenneth W.; Heinl, Robert Debs (1995). Handbook for Marine NCOs. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-238-2.

- ^ "Historia de La Infanteria de Marina" (in Spanish). Spanish Navy Marines. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Londoño, Sancho de: Discurso sobre la forma de reducir la disciplina militar a mejor y antiguo estado, p. 14.

- ^ Lynch, John (1992). The Hispanic World in Crisis and Change, 1578–1700. Cambridge: Blackwell, p. 117.

- ^ Eduardo de Mesa (2014, p. 70)

- ^ Mendoza, Ana. "Spanish Tercios 1536–1704".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Davies, T. R. 1961.

- ^ Lynch, John (1964). Spain Under the Habsburgs, Volume One: Empire and Absolutism, 1516 to 1598. Oxford: Blackwell, p. 109.

- ^ Lynch. Spain Under the Habsburgs, p. 200.

- ^ Israel, The Dutch Republic, p. 185.

- ^ Lynch. Spain Under the Habsburgs, p. 284.

- ^ Laínez, Fernando Martínez (2011). Vientos de Gloria : grandes victorias de la historia de España. Madrid: Espasa. ISBN 9788467035605.

- ^ "Francisco de Medrano y Bazán | Real Academia de la Historia". dbe.rah.es. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Contenido - Spanish army". ejercito.defensa.gob.es. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ Geográfica (Spain), Real Sociedad (1906). Boletín (in Spanish).

Bibliography

[edit]- Christon I. Archer, John R. Ferris, Holger H. Herwig, Timothy H. E. Travers – For a history of Spanish arms in the 16th and 17th centuries.

- Davies, T. R. (1961). The Golden Century of Spain 1501–1621. London: Macmillan & Co. – Brief description of the birth of the Spanish tercio.

- Eduardo de Mesa (2014). The Irish in the Spanish Armies in the Seventeenth Century. Boydell & Brewer, Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-951-4. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt6wp8jf. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- López, Ignacio J.N. The Spanish Tercios 1536–1704. Osprey Publishing – The history of the tercio from its antecedents to its decline and ultimate realignment into a regimental system in 1704.

- Spanish Tercio Tactics Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Renaissance Armies: The Spanish (myArmoury.com article)

- Spanish web site – Honors Alonso Pita da Veiga the most heroic Spaniard at the Battle of Pavia (Italy) 1525.

- [1] Non-Official Web siteof the Modern "Spanish Marines" (in existence since 1537 few years after Battle of Pavia (Italy) 1525 and well before the Battle of Lepanto (Greece) 1571).

- The Spanish Army of the Thirty Years’ War

- List of Tercios

- Lorraine White – The Experience of Spain’s Early Modern Soldiers: Combat, Welfare and Violence

- Pierre de Bourdeille, Gentilezas y bravuconadas de los españoles (r/p Mosand, Madrid, 1996)

- Marcos de Isaba, Cuerpo enfermo de la milicia española Ministry of Defence, Madrid (Brussels, 1589)

- Sancho de Londoño, El discurso sobre la forma de reducir la disciplina militar a mejor y antiguo estado Ministry of Defence, Madrid (Brussels, 1589)

- Bernardino de Escalante, Diálogos del arte militar Ministry of Defence, Madrid (1583)

- Martín de Eguiluz, Milicia, Discurso y Regla militar Ministry of Defence, Madrid (pre-1591)

- Diego de Salazar, Tratado de Re Militari Ministry of Defence, Madrid(1590)

- Serafín María de Soto, Conde de Clonard, Album de la infantería española (1861)

- Rene Quatrefages, Los Tercios (Madrid, ediciones Ejército, 1983)

- Inspección de Infantería, La infantería en torno al siglo del oro (Madrid, ediciones Ejército, 1993)

- Julio Albi de la Cuesta, De Pavia a Rocroi: los Tercios de Infantería española en los siglos XVI y XVII (Madrid, Balkan, 1999)

- Enrique Martínez Ruiz, Los soldados del Rey (Madrid, Actas, 2008)

- Pierre Picouet, Les Tercios Espagnols 1600–1660 (in French – Auzielle, LRT, 2010)