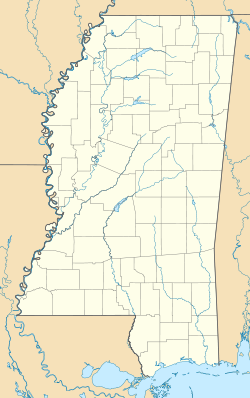

Laurel, Mississippi

Laurel, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: "The City Beautiful" | |

| Coordinates: 31°41′51″N 89°8′22″W / 31.69750°N 89.13944°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Jones |

| Incorporated | 1882 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Johnny Magee |

| Area | |

• Total | 16.54 sq mi (42.83 km2) |

| • Land | 16.24 sq mi (42.05 km2) |

| • Water | 0.30 sq mi (0.78 km2) |

| Elevation | 269 ft (82 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 17,161 |

| • Density | 1,056.97/sq mi (408.10/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 39440–39443 |

| Area code(s) | 601, 769 |

| FIPS code | 28-39640 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0672321 |

| Website | www |

Laurel is a city in and the second county seat of Jones County, Mississippi, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 17,161.[2] Laurel is northeast of Ellisville, the first county seat, which contains the first county courthouse. It has the second county courthouse, as Jones County has two judicial districts. Laurel is the headquarters of the Jones County Sheriff's Department, which administers in the county. Laurel is the principal city of a micropolitan statistical area named for it. Major employers include Howard Industries, Sanderson Farms, Masonite International, Family Health Center, Howse Implement, Thermo-Kool, and South Central Regional Medical Center. Laurel is home to the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Mississippi's oldest art museum, established by the family of Lauren Eastman Rogers.

History

[edit]

Following the 1881 construction of the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad through the area,[3] economic development occurred rapidly. The city of Laurel was incorporated in 1882, with timber as the impetus.[4] Yellow pine forests in the region fueled the industry. The city was named for thickets of mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) native to the original town site.[5]

Located in the heart of the piney woods ecoregion of the southeastern United States, the land site that eventually became Laurel was densely covered with forests of virgin longleaf pine, making the area attractive to pioneering lumberjacks and sawmill operators in the late 19th century.

In 1881, business partners John Kamper and A.M. Lewin constructed a small lumber mill on the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad. Kamper and Lewin's mill was in an area that later became Laurel's First Avenue. The next year, in response to a Post Office Department request to provide a postal delivery name for their mill and its surrounding lumber camp, Kamper and Lewin submitted the name "Lawrell" as an homage to the area's naturally growing mountain laurel bushes. Federal postal officials soon "corrected" the peculiar spelling, giving the town its current spelling.

During its first decade or so, Laurel was little more than a glorified lumber camp surrounding Kamper and Lewin's primitive sawmill. By 1891, Kamper's company was on the verge of bankruptcy, leading Kamper to sell the mill and extensive land holdings in the area (more than 15,000 acres), to Clinton, Iowa, lumber barons Lauren Chase Eastman and George and Silas Gardiner, founders of the Eastman-Gardiner Company.

After their purchase, Eastman and the Gardiner brothers decided to make substantial improvements to Laurel's lumber operations by constructing a new, much larger, state-of-the-art lumber mill. In 1893, the new Eastman-Gardiner Company mill began operations, using the best technology and labor-saving devices of the day.

By the early 1900s, the success of Eastman-Gardner Company's operations in Laurel and the region's superabundance of timber began to attract other lumber industrialists' attention. In 1906, the Gilchrist-Fordney Company, whose founders hailed from Alpena, Michigan, began construction on their own lumber mill in Laurel. By March 1907 the Mobile, Jackson and Kansas City Railroad made four stops a day in Laurel which was 110 track miles from Mobile, Alabama. The trains not only carried passengers but hauled freight that included lumber from nine sawmills. Together they produced around 583,000 board feet (bf) a day. WM Carter Lumber Company (milepost 108) 20,000 bf, Eastman-Gardner & Company 200,000 bf, Kingston Lumber Company 200,000 bf, Geo Beckner (shingles) 20,000 bf, John Lindsey 15,000 bf, HC Card Lumber Company (hard wood) 30,000 bf, Lindsey Wagon works mill 15,000 bf, WM Carter (planer) 75,000 bf, and Stainton and Weems 8,000 bf.[6]

The Wausau-Southern mill from Wausau, Wisconsin, followed in 1911, and the Marathon mill from Memphis, Tennessee, in 1914. By the end of World War I, Laurel's mills produced and shipped more yellow pine lumber than those of any other location in the world. By the 1920s—the peak of Laurel's lumber production—the area's four mills were producing a total of one million board feet of lumber per day. Laid end to end, that amount of lumber would stretch 189 miles.[7]

The economic prosperity of Laurel's timber era (1893–1937) and "timber families" created the famed Laurel Central Historic District as a byproduct.[8] The area is considered Mississippi's largest, finest, and most intact collection of early-20th-century architecture and has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since September 4, 1987,[9] for both its historical value and its wide variety of architectural styles. Many of the district's homes and buildings are featured on the HGTV series Home Town. In addition to influencing a diverse architectural district, Laurel's "timber families" influenced the building of the town's broad avenues, the design of numerous public parks, and the development of strong public schools.[10]

The city's population grew markedly during the early 20th century because rural people were attracted to manufacturing jobs and the economic takeoff of Masonite International. Mechanization of agriculture reduced the number of farming jobs. In 1942, Howard Wash, a 45-year-old African-American man who had been convicted of murder, was dragged from jail and lynched by a mob.[11] The city reached its peak census population in 1960, and has declined about one third since then.

Geography

[edit]Laurel is in north-central Jones County, 8 miles (13 km) northeast of Ellisville, the first county seat. Interstate 59 and U.S. Route 11 pass through Laurel, both highways leading southwest 30 miles (48 km) to Hattiesburg and northeast 57 miles (92 km) to Meridian. U.S. Route 84 passes through the south side of the city, leading east 30 miles (48 km) to Waynesboro and west 27 miles (43 km) to Collins. Mississippi Highway 15 passes through the south and west sides of the city, leading northwest 24 miles (39 km) to Bay Springs and southeast 28 miles (45 km) to Richton.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Laurel has an area of 16.5 square miles (42.8 km2), of which 15.8 square miles (40.8 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.8 km2), or 1.81%, is water. The city lies on a low ridge between Tallahala Creek to the east and Tallahoma Creek to the west. Tallahoma Creek joins Tallahala Creek south of Laurel, and Tallahala Creek continues south to join the Leaf River, part of the Pascagoula River watershed.

Climate

[edit]The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Laurel has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[12] The area is also prone to tornadoes. On December 28, 1954, an F3 tornado tore directly through the city, injuring 25 people.[13]

| Climate data for Laurel, Mississippi, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1891–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

85 (29) |

91 (33) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

106 (41) |

106 (41) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

86 (30) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 75.3 (24.1) |

78.8 (26.0) |

83.6 (28.7) |

86.2 (30.1) |

91.6 (33.1) |

95.4 (35.2) |

97.4 (36.3) |

97.3 (36.3) |

94.7 (34.8) |

89.7 (32.1) |

81.8 (27.7) |

77.2 (25.1) |

98.5 (36.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.9 (15.5) |

64.7 (18.2) |

71.9 (22.2) |

78.6 (25.9) |

85.4 (29.7) |

90.9 (32.7) |

93.2 (34.0) |

92.7 (33.7) |

88.7 (31.5) |

80.0 (26.7) |

69.7 (20.9) |

62.4 (16.9) |

78.2 (25.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.3 (8.5) |

51.5 (10.8) |

58.5 (14.7) |

65.2 (18.4) |

72.9 (22.7) |

79.4 (26.3) |

81.8 (27.7) |

81.2 (27.3) |

76.6 (24.8) |

66.2 (19.0) |

55.8 (13.2) |

49.7 (9.8) |

65.5 (18.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 34.6 (1.4) |

38.3 (3.5) |

45.0 (7.2) |

51.7 (10.9) |

60.4 (15.8) |

67.9 (19.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

69.7 (20.9) |

64.4 (18.0) |

52.5 (11.4) |

41.8 (5.4) |

36.9 (2.7) |

52.8 (11.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 20.5 (−6.4) |

24.8 (−4.0) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

38.2 (3.4) |

47.6 (8.7) |

60.4 (15.8) |

65.6 (18.7) |

64.5 (18.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

37.6 (3.1) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

24.3 (−4.3) |

18.4 (−7.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 3 (−16) |

10 (−12) |

17 (−8) |

27 (−3) |

36 (2) |

45 (7) |

56 (13) |

54 (12) |

40 (4) |

23 (−5) |

16 (−9) |

3 (−16) |

3 (−16) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.07 (154) |

5.11 (130) |

5.46 (139) |

5.10 (130) |

4.34 (110) |

5.46 (139) |

5.38 (137) |

5.48 (139) |

3.94 (100) |

3.48 (88) |

4.06 (103) |

5.76 (146) |

59.64 (1,515) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.3 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 11.3 | 13.1 | 10.9 | 7.6 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 10.5 | 117.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA[14] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[15] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 3,193 | — | |

| 1910 | 8,465 | 165.1% | |

| 1920 | 13,037 | 54.0% | |

| 1930 | 18,017 | 38.2% | |

| 1940 | 20,598 | 14.3% | |

| 1950 | 25,038 | 21.6% | |

| 1960 | 27,889 | 11.4% | |

| 1970 | 24,145 | −13.4% | |

| 1980 | 21,897 | −9.3% | |

| 1990 | 18,827 | −14.0% | |

| 2000 | 18,393 | −2.3% | |

| 2010 | 18,540 | 0.8% | |

| 2020 | 17,161 | −7.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 4,465 | 26.02% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 10,642 | 62.01% |

| Native American | 35 | 0.2% |

| Asian | 109 | 0.64% |

| Pacific Islander | 2 | 0.01% |

| Other/Mixed | 453 | 2.64% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,455 | 8.48% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 17,161 people, 6,825 households, and 4,278 families residing in the city.

Government

[edit]

City government has a mayor-council form. The mayor is elected at-large. Council members are elected from single-member districts.[18]

- City officials

- Johnny Magee, mayor[19]

- Jason Capers, Ward 1 council member

- Kevin Kelly, Ward 2 council member

- Tony Thaxton, Ward 3 council member

- George Carmichael, Ward 4 council member

- Andrea Ellis, Ward 5 council member

- Grace Amos, Ward 6 council member

- Shirley Keys-Jordan, Ward 7 council member

The U.S. Postal Service operates the Laurel Post Office and the Choctaw Post Office, both in Laurel.[20][21]

The Mississippi Department of Mental Health South Mississippi State Hospital Crisis Intervention Center is in Laurel.[22]

Education

[edit]Almost all of Laurel is in the Laurel School District. Small portions are in the Jones County School District.[23]

- The portion in the Laurel School District is served by Laurel High School.

Private schools:

- Laurel Christian School

- Laurel Christian High School

- St. John's Day School (affiliated with the Episcopal Church)[24]

Jones County is within the district served by the Jones College community college.[25]

Media

[edit]- WDAM-TV

- WHLT-TV

- WLAU (99.3 FM, SuperTalk Mississippi)

- The Laurel Leader-Call newspaper

- The Chronicle[26]

- WXRR (104.5 FM, "Rock104")

- WBBN (95.9 FM, "B-95")

- Impact Laurel[27]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Amtrak's Crescent train connects Laurel with New York City; Philadelphia; Baltimore; Washington, D.C.; Charlotte, North Carolina; Atlanta; Birmingham, Alabama; and New Orleans. Laurel's Amtrak station is at 230 North Maple Street.

Hattiesburg–Laurel Regional Airport is in an unincorporated area in Jones County near Moselle,[28] 21 miles (34 km) southwest of Laurel.

- Major highways

Notable people

[edit]- Jake Allen, professional football player

- Lance Bass, musician

- Marsha Blackburn, U.S Senator, former congresswoman from Tennessee

- Ralph Boston, Olympic champion athlete

- Correll Buckhalter, former professional football player

- Lee Calhoun, Olympic champion athlete

- Jason Campbell, professional football player

- David and the Giants, Christian rock band

- Akeem Davis, professional football player

- Mary Elizabeth Ellis, actress

- Carroll Gartin, former lieutenant governor

- Ed Hinton, sportswriter

- Tess Holliday, model

- Robert Hyatt, computer scientist

- BoPete Keyes, professional football player

- Diane Ladd, actress, raised in Meridian[29]

- Mark A. Landis, painter

- Tom Lester, television actor

- Mundell Lowe, jazz musician

- Doug Marlette, Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist

- Chris McDaniel, attorney and politician

- Mary Mills, professional golfer

- Ben and Erin Napier, Home Town television personalities

- Kenny Payne, former professional basketball player

- Charles W. Pickering, politician and judge

- Chip Pickering, former congressman

- Stacey Pickering, State Auditor of Mississippi

- Clinton Portis, former professional football player

- Parker Posey, actress[30]

- Leontyne Price, opera singer

- Omeria McDonald Scott, state representative

- Ray Walston, actor

- Lloyd Wells, musician

- Will Wheaton, singer-songwriter

In popular culture

[edit]Laurel residents Erin and Ben Napier are featured in the HGTV series Home Town, which premiered on March 21, 2017.[31] The show portrays renovations of local homes in and near Laurel.

In Tennessee Williams' play A Streetcar Named Desire, fictional Laurel native Blanche DuBois is known here as a "woman of loose morals" who, after the loss of her family estate "Belle Reve", frequents the Hotel Flamingo as told to Stanley by the merchant Kiefaber. In an argument, Blanche tells Harold Mitchell she's brought many victims into her web, and calls the hotel the Tarantula Arms rather than the Hotel Flamingo.

Singer-songwriter Steve Forbert had a hit with the song "Goin' Down to Laurel" (released on his 1978 album Alive on Arrival) which refers to visiting the town of Laurel.

See also

[edit]- Laurel Black Cats, semi-professional baseball team

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Census – Geography Profile". archive.ph. January 11, 2022. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ "Mississippi Railroads".

- ^ Thames, Bill. Walking Tour of Historic Laurel Homes. Laurel, Mississippi: Lauren Rogers Museum of Art. p. 6.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. US Government Printing Office. p. 182.

- ^ "Mobile,_Jackson_and_Kansas_City_Railroad" (PDF). p. 3 & 6. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ "LRMA – Lauren Rogers Museum of Art | Laurel, Mississippi". Lrma.org. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "A Story of Growth – The City of Laurel, MS". Laurelms.com. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places - Mississippi (MS), Jones County". Nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ Lauren Rogers Museum of Art. The University Press of Mississippi. 2003. pp. ix. ISBN 1-57806-557-7.

- ^ "Mississippi Mob Lynches a Slayer". New York Times. October 18, 1942. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ "Laurel, Mississippi Kloppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "Mississippi F3". Tornado History Projects. Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Laurel, MS". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Jackson". National Weather Service. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ "Government". The City of Laurel Mississippi. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Office of the Mayor". The City of Laurel Mississippi. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Post Office Location – LAUREL Archived 2012-08-21 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on November 1, 2010.

- ^ "Post Office Location – CHOCTAW Archived 2012-08-21 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on November 1, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived 2012-03-14 at the Wayback Machine." South Mississippi State Hospital. Retrieved on November 1, 2010. "SMSH Crisis Intervention Center 934 West Drive Laurel, MS 39440."

- ^ "2020 CENSUS – SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Jones County, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "About Our School". St. John's Day School. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ "Profile: Historical Sketch". Jones College. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "The Chronicle". Thechronicle.ms. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ "IMPACT". Pageflip.site. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ "Contact." Hattiesburg-Laurel Regional Airport. Retrieved on July 15, 2011. "Our Address Airport Director, 1002 Terminal Dr. Moselle, MS 39459"

- ^ Davis Davidson, June; Putnam, Richelle (2013). Legendary Locals of Meridian. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1467100793.

- ^ Schulman, Michael (July 2, 2015). "Parker Posey's Offbeat Glamour". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ Shinners, Rebecca (March 10, 2017). "9 Reasons You Should Be Watching HGTV's Newest Show 'Home Town'". Country Living. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Victoria E. Bynum, The Free State of Jones: Mississippi's Longest Civil War (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001, 2016)

- Alex Heard, The Eyes of Willie McGee: A Tragedy of Race, Sex and Secrets in the Jim Crow South (New York: Harper, 2011)

- Nollie W. Hickman, Mississippi Harvest: Lumbering in the Longleaf Pine Belt, 1840–1915 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, new edition, 2009)

- Gilbert H. Hoffman and Tony Howe, Yellow Pine Capital: The Laurel, Mississippi Story (Toot Toot Publishing Company, 2010)

- Charles Marsh, The Last Days: A Son's Story of Sin and Segregation at the Dawn of a New South (New York: Basic Books, 2000)

- Cleveland Payne, The Oak Park Story: A Cultural History, 1928–1970 (National Oak Park High School Alumni Association, 1988)

- Cleveland Payne, Laurel: A History of the Black Community, 1882–1962 (Cleveland Payne, 1990)

External links

[edit]- City of Laurel official website

- Scrapbook re: Laurel, Mississippi (MUM00404), owned by the University of Mississippi.