Sonnet 20

| Sonnet 20 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

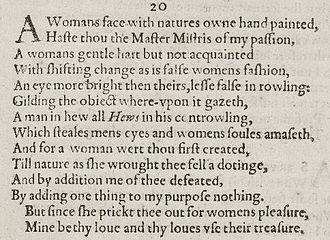

Sonnet 20 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 20 is one of the best-known of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. Part of the Fair Youth sequence (which comprises sonnets 1-126), the subject of the sonnet is widely interpreted as being male, thereby raising questions about the sexuality of its author. In this sonnet (as in, for example, Sonnet 53) the beloved's beauty is compared to both a man's and a woman's.

Structure

[edit]Sonnet 20 is a typical English or Shakespearean sonnet, containing three quatrains and a couplet for a total of fourteen lines. It follows the rhyme scheme of this type of sonnet, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. It employs iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. "Only this sonnet about gender has feminine rhymes throughout."[2]

The first line exemplifies regular iambic pentameter with a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending:

× / × / × / × / × / (×) A woman's face with nature's own hand painted, (20.1)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

Context

[edit]Sonnet 20 is most often considered to be a member of the "Fair Youth" group of sonnets, in which most scholars agree that the poet addresses a young man. This interpretation contributes to a common assumption of the homosexuality of Shakespeare, or at least the speaker of his sonnet. The position of Sonnet 20 also influences its analysis and examinations. William Nelles, of the University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth, claims that,

Sonnet 20 splits readers into two groups: those who see an end to any clear sequence after this point, and those who read on, finding a narrative line connecting the rest of the sonnets in a meaningful pattern.[3]

Scholars have suggested countless motivations or means of organizing Shakespeare's sonnets in a specific sequence or system of grouping. Some see the division between the sonnets written to the "young man", while others do not. A number of academics believe the sonnets may be woven into some form of complex narrative, while Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells confidently assert that the sonnets are "better thought of as a collection than a sequence, since…the individual poems do not hang together from beginning to end as a single unity…Though some of the first 126 poems in the collection unquestionably relate to a young man, others could relate to either a male or female."[3]

Sexuality

[edit]The modern reader may read sonnet 20 and question whether or not Shakespeare's sexuality is reflected in this sonnet. When looking at the sexual connotations in this sonnet it is important to reflect on what homoeroticism meant during the time that Shakespeare was writing. Casey Charles discusses the idea that there was no official identity for a gay person at this time. There were words that identified what we would consider to be homosexual behaviour, but the idea of a "gay culture" or "gay identity" did not exist.[4] Charles goes on to say that early modern laws against sodomy had very few transgressors, which means that either people did not engage in homosexual behavior or these acts were more socially acceptable than the modern reader would think. Shakespeare's awareness of the possible homoeroticism in Sonnet 20 does not necessarily illuminate whether or not he himself was actually practicing homosexual behavior.[4]

One of the most famous accounts to raise the issue of homoeroticism in this sonnet is Oscar Wilde's short story "The Portrait of Mr. W.H.", in which Wilde, or rather the story's narrator, describes the puns on "will" and "hues" throughout the sonnets, and particularly in the line in Sonnet 20, "A man in hue all hues in his controlling," as referring to a seductive young actor named Willie Hughes who played female roles in Shakespeare's plays. However, there is no evidence for the existence of any such person.[5]

Analysis

[edit]While there is much evidence that suggests the narrator's homosexuality, there are also countless academics[who?] who have argued against the theory. Both approaches can be used to analyze the sonnet.

Philip C. Kolin, of the University of Southern Mississippi, interprets several lines from the first two quatrains of Sonnet 20 as written by a homosexual figure. One of the most common interpretations of line 2 is that the speaker believes, "the young man has the beauty of a woman and the form of a man...Shakespeare bestows upon the young man feminine virtues divorced from all their reputedly shrewish infidelity."[6] In other words, the young man possesses all the positive qualities of a woman, without all of her negative qualities. The narrator seems to believe that the young man is as beautiful as any woman, but is also more faithful and less fickle. Kolin also argues that, "numerous, though overlooked, sexual puns run throughout this indelicate panegyric to Shakespeare's youthful friend."[6] He suggests the reference to the youth's eyes, which gild the objects upon which they gaze, may also be a pun on "gelding…The feminine beauty of this masculine paragon not only enhances those in his sight but, with the sexual meaning before us, gelds those male admirers who temporarily fall under the sway of the feminine grace and pulchritude housed in his manly frame."[6]

Amy Stackhouse of Iona University[7] explains that the form of the sonnet (written in iambic pentameter with an extra-unstressed syllable on each line) lends itself to the idea of a "gender-bending" model. The unstressed syllable is a feminine rhyme, yet the addition of the syllable to the traditional form may also represent a phallus.[8] Sonnet 20 is one of only two in the sequence with feminine endings to its lines; the other is Sonnet 87.[9] Stackhouse emphasizes the ambiguity of the addressee's gender throughout the sonnet, which is resolved only in the final three lines. She writes that many parts of the sonnet—for example the term "master mistress"—maintain uncertainty around the gender of the sonnet's subject.[8] Likewise, in her analysis, Stackhouse discusses nature and Nature, a feminine personification of nature. In her conclusion, Stackhouse writes that Nature "in the act of creation fell in love with her creature and added a penis".[8] Patrick Mahony also interperts the transsexuality of the subject, stating "Dame Nature fell in love with one of her female creatures, and to overcome her own frustration turns that creature into a man. This transsexual, a cynosure for both admiring sexes, has masculine and feminine traits"[10]

This idea of nature is also reflected in Philip C. Kolin's analysis of the last part of the poem as well.[6] Kolin goes on to say that the phrase "to my purpose nothing" also reflects this natural aspect of being created for women's pleasure. In this, however, he takes no account of Shakespeare's common pun of "nothing" ("O") to mean vagina.[11] Whereas Stackhouse would argue the poem is almost gender neutral, Kolin would argue that the poem is "playful" and "sexually (dualistic)".[6]

Martin B. Friedman, of California State College, Hayward, holds an entirely different view. Friedman believes Sonnet 20 is written by a masculine heterosexual figure involved in a heteronormative friendship, and that the various puns and language used historically related to sports present during Shakespeare's time. For example, he argues, “the terms ‘Master’ and ‘Mistress’[of line 2], used interchangeably to refer, as here, to something which is an object of passionate interest of a center of attention, come from the game of bowls.”[12] He continues to build connections between several phrases and, what he believes to be, references to terms used in gambling, more specifically in the game of bowls, which involves the rolling of a dice. Friedman claims, “And the imagery recurs in line 5: ‘An eye more bright then theirs, lesse false in rowling.’”[13] However, Cathy Shrank contends that Friedman's article was one among many attempts "to ‘save’ Shakespeare from the apparent ‘shame’ of homoeroticism".[14] Robert Matz also notes that John Benson's Poems positions Sonnet 20 in a way to imply a platonic friendship, further contending that Benson often arranged poems and assigned titles that did not exist in order to infer the subject of many of the poems had been women.[15]

In other media

[edit]On his eighth studio album, Rufus Wainwright set Sonnet 20 to music on Take All My Loves: 9 Shakespeare Sonnets. And originally on his album "All days are Nights: Songs for Lulu." Where he also sets Sonnets 10 and 43.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ^ Booth, Stephen (2000) [1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New Haven: Yale Nota Bene [Yale University Press]. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-300-08506-8.

- ^ a b William Nelles, "Sexing Shakespeare's Sonnets: Reading Beyond Sonnet 20," English Literary Renaissance Volume 39, Issue 1, February 2009: 128-140. Abstract

- ^ a b Charles, Casey. "Was Shakespeare gay? Sonnet 20 and the politics of pedagogy." College Literature 25.3 (1998): 35-52. EBSCOhost. Web. 10 Nov. 2009.

- ^ A "hue" was a servant; see OED: "hewe". The original word in the Quarto for "hues" is "Hews".

- ^ a b c d e Kolin, Philip C. "Shakespeare's Sonnet 20." Explicitor 45.1 (1986): 10-12. Print.

- ^ "Amy Stackhouse, Ph.D." Iona University. 28 August 2024. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Stackhouse, Amy D. "Shakespeare's Half-Foot: Gendered Prosody in Sonnet 20." Explicitor 65 (2006): 202-04. Print.

- ^ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 20". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Mahony, Patrick (1979). "Shakespeare's Sonnet Number 20: Its Symbolic Gestalt". American Imago. 36 (1): 69–70. ISSN 0065-860X. JSTOR 26303358.

- ^ Williams, Gordon (1997). "nothing". Shakespeare's Sexual Language: A Glossary. London: Athlone Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8264-9134-3.

- ^ Martin B. Friedman, Shakespeare’s ‘Master Mistris’: Image and Tone in Sonnet 20, 189-191.

- ^ Martin B. Friedman, Shakespeare’s ‘Master Mistris’: Image and Tone in Sonnet 20, 189-191.

- ^ Shrank, Cathy (September 2009). "Reading Shakespeare's Sonnets : John Benson and the 1640 Poems". Shakespeare. 5 (3): 271–291. doi:10.1080/17450910903138054. ISSN 1745-0918.

- ^ Matz, Robert (2010). "The Scandals of Shakespeare's Sonnets". ELH. 77 (2): 487–489. doi:10.1353/elh.0.0082. ISSN 1080-6547.

References

[edit]- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.