Some Thoughts Concerning Education

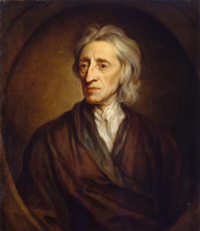

Some Thoughts Concerning Education is a 1693 treatise on the education of gentlemen written by the English philosopher John Locke.[1] For over a century, it was the most important philosophical work on education in England. It was translated into almost all of the major written European languages during the eighteenth century, and nearly every European writer on education after Locke, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, acknowledged its influence.

In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), Locke outlined a new theory of mind, contending that the mind is originally a tabula rasa or "blank slate"; that is, it did not contain any innate ideas at birth. Some Thoughts Concerning Education explains how to educate that mind using three distinct methods: the development of a healthy body; the formation of a virtuous character; and the choice of an appropriate academic curriculum.

Locke wrote the letters that would eventually become Some Thoughts for an aristocratic friend, but his advice had a broader appeal since his educational principles suggested anyone could acquire the same kind of character as the aristocrats for whom Locke originally intended the work.

Historical context

[edit] |

| Part of a series on |

| John Locke |

|---|

|

Works (listed chronologically) |

| People |

| Related topics |

Rather than writing a wholly original philosophy of education, Locke, it seems, deliberately attempted to popularise several strands of seventeenth-century educational reform at the same time as introducing his own ideas. English writers such as John Evelyn, John Aubrey, John Eachard, and John Milton had previously advocated "similar reforms in curriculum and teaching methods," but they had not succeeded in reaching a wide audience.[2] Curiously, though, Locke proclaims throughout his text that his is a revolutionary work; as Nathan Tarcov, who has written an entire volume on Some Thoughts, has pointed out, "Locke frequently explicitly opposes his recommendations to the 'usual,' 'common,' 'ordinary,' or 'general' education."[3]

As England became increasingly mercantilist and secularist, the humanist educational values of the Renaissance, which had enshrined scholasticism, came to be regarded by many as irrelevant.[4] Following in the intellectual tradition of Francis Bacon, who had challenged the cultural authority of the classics, reformers such as Locke, and later Philip Doddridge, argued against Cambridge and Oxford's decree that "all Bachelor and Undergraduates in their Disputations should lay aside their various Authors, such that caused many dissensions and strives in the Schools, and only follow Aristotle and those that defend him, and take their Questions from him, and that they exclude from the Schools all steril and inane Questions, disagreeing from the ancient and true Philosophy [sic]."[5] Instead of demanding that their sons spend all of their time studying Greek and Latin texts, an increasing number of families began to demand a practical education for their sons; by exposing them to the emerging sciences, mathematics, and the modern languages, these parents hoped to prepare their sons for the changing economy and, indeed, for the new world they saw forming around them.[6]

Text

[edit]In 1684, Mary Clarke and her husband Edward asked their friend John Locke for advice on raising their son Edward Jr.; Locke responded with a series of letters that eventually became Some Thoughts Concerning Education.[7][8] But it was not until 1693, encouraged by the Clarkes and another friend, William Molyneux, that Locke actually published the treatise; Locke, "timid" when it came to public exposure, decided to publish the text anonymously.[9]

Although Locke revised and expanded the text five times before he died,[10] he never substantially altered the "familiar and friendly style of the work."[11] The "Preface" alerted the reader to its humble origins as a series of letters and, according to Nathan Tarcov, who has written an entire volume on Some Thoughts, advice that otherwise might have appeared "meddlesome" became welcome. Tarcov claims Locke treated his readers as his friends and they responded in kind.[11]

Pedagogical theory

[edit]Of Locke's major claims in the Essay Concerning Human Understanding and Some Thoughts Concerning Education, two played a defining role in eighteenth-century educational theory. The first is that education makes the man; as Locke writes at the opening of his treatise, "I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education."[12] In making this claim, Locke was arguing against both the Augustinian view of man, which grounds its conception of humanity in original sin, and the Cartesian position, which holds that man innately knows basic logical propositions.[13] In his Essay Locke posits an "empty" mind—a tabula rasa—that is "filled" by experience. In describing the mind in these terms, Locke was drawing on Plato's Theatetus, which suggests that the mind is like a "wax tablet".[14] Although Locke argued strenuously for the tabula rasa theory of mind, he nevertheless did believe in innate talents and interests.[15] For example, he advises parents to watch their children carefully to discover their "aptitudes," and to nurture their children's own interests rather than force them to participate in activities which they dislike[16]—"he, therefore, that is about children should well study their natures and aptitudes and see, by often trials, what turn they easily take and what becomes them, observe what their native stock is, how it may be improved, and what it is fit for."[17]

Locke also discusses a theory of the self. He writes: "the little and almost insensible impressions on our tender infancies have very important and lasting consequences."[18] That is, the "associations of ideas" made when young are more significant than those made when mature because they are the foundation of the self—they mark the tabula rasa. In the Essay, in which he first introduces the theory of the association of ideas, Locke warns against letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are associated with the darkness, for "darkness shall ever afterwards bring with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other."[19]

Locke's emphasis on the role of experience in the formation of the mind and his concern with false associations of ideas has led many to characterise his theory of mind as passive rather than active, but as Nicholas Jolley, in his introduction to Locke's philosophical theory, points out, this is "one of the most curious misconceptions about Locke."[20] As both he and Tarcov highlight, Locke's writings are full of directives to seek out knowledge actively and reflect on received opinion; in fact, this was the essence of Locke's challenge to innatism.[21]

Body and mind

[edit]Locke advises parents to carefully nurture their children's physical "habits" before pursuing their academic education.[22] As many scholars have remarked, it is unsurprising that a trained physician, as Locke was, would begin Some Thoughts with a discussion of children's physical needs, yet this seemingly simple generic innovation has proven to be one of Locke's most enduring legacies—Western child-rearing manuals are still dominated by the topics of food and sleep.[23] To convince parents that they must attend to the health of their children above all, Locke quotes from Juvenal's Satires—"a sound mind in a sound body." Locke firmly believed that children should be exposed to harsh conditions while young to inure them to, for example, cold temperatures when they were older: "Children [should] be not too warmly clad or covered, winter or summer" (Locke's emphasis), he argues, because "bodies will endure anything that from the beginning they are accustomed to."[24] Furthermore, to prevent a child from catching chills and colds, Locke suggests that "his feet to be washed every day in cold water, and to have his shoes so thin that they might leak and let in water whenever he comes near it" (Locke's emphasis).[25] Locke posited that if children were accustomed to having sodden feet, a sudden shower that wet their feet would not cause them to catch a cold. Such advice (whether followed or not) was quite popular; it appears throughout John Newbery's children's books in the middle of the eighteenth century, for example, the first best-selling children's books in England.[26] Locke also offers specific advice on topics ranging from bed linens to diet to sleeping regimens.

Virtue and reason

[edit]Locke dedicates the bulk of Some Thoughts Concerning Education to explaining how to instill virtue in children. He defines virtue as a combination of self-denial and rationality: "that a man is able to deny himself his own desires, cross his own inclinations, and purely follow what reason directs as best, though the appetite lean the other way" (Locke's emphasis).[27] Future virtuous adults must be able not only to practice self-denial but also to see the rational path. Locke was convinced that children could reason early in life and that parents should address them as reasoning beings. Moreover, he argues that parents should, above all, attempt to create a "habit" of thinking rationally in their children.[28] Locke continually emphasises habit over rule—children should internalise the habit of reasoning rather than memorise a complex set of prohibitions. This focus on rationality and habit corresponds to two of Locke's concerns in the Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Throughout the Essay, Locke bemoans the irrationality of the majority and their inability, because of the authority of custom, to change or forfeit long-held beliefs.[29] His attempt to solve this problem is not only to treat children as rational beings but also to create a disciplinary system founded on esteem and disgrace rather than on rewards and punishments.[30] For Locke, rewards such as sweets and punishments such as beatings turn children into sensualists rather than rationalists; such sensations arouse passions rather than reason.[31] He argues that "such a sort of slavish discipline makes a slavish temper" (Locke's emphasis).[32]

What is important to understand is what exactly Locke means when he advises parents to treat their children as reasoning beings. Locke first highlights that children "love to be treated as Rational Creatures," thus parents should treat them as such. Tarcov argues that this suggests children can be considered rational only in that they respond to the desire to be treated as reasoning creatures and that they are "motivated only [by] rewards and punishments" to achieve that goal.[33]

Ultimately, Locke wants children to become adults as quickly as possible. As he argues in Some Thoughts, "the only fence against the world is a thorough knowledge of it, into which a young gentleman should be entered by degrees as he can bear it, and the earlier the better."[34] In the Second Treatise on Government (1689), he contends that it is the parents' duty to educate their children and to act for them because children, though they have the ability to reason when young, do not do so consistently and are therefore usually irrational; it is the parents' obligation to teach their children to become rational adults so that they will not always be fettered by parental ties.[35]

Academic curriculum

[edit]Locke does not dedicate much space in Some Thoughts Concerning Education to outlining a specific curriculum; he is more concerned with convincing his readers that education is about instilling virtue and what Western educators would now call critical-thinking skills.[36] Locke maintains that parents or teachers must first teach children how to learn and to enjoy learning. As he writes, the instructor "should remember that his business is not so much to teach [the child] all that is knowable, as to raise in him a love and esteem of knowledge; and to put him in the right way of knowing and improving himself."[37] But Locke does offer a few hints as to what he thinks a valuable curriculum might be. He deplores the long hours wasted on learning Latin and argues that children should first be taught to speak and write well in their native language,[38] particularly recommending Aesop's Fables. Most of Locke's recommendations are based on a similar principle of utility.[39] So, for example, he claims that children should be taught to draw because it would be useful to them on their foreign travels (for recording the sites they visit), but poetry and music, he says, are a waste of time. Locke was also at the forefront of the scientific revolution and advocated the teaching of geography, astronomy, and anatomy.[40] Locke's curricular recommendations reflect the break from scholastic humanism and the emergence of a new kind of education—one emphasising not only science but also practical professional training. Locke also recommended, for example, that every (male) child learn a trade.[41] Locke's pedagogical suggestions marked the beginning of a new bourgeois ethos that would come to define Britain in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[42]

Class

[edit]When Locke began writing the letters that would eventually become Some Thoughts on Education, he was addressing an aristocrat, but the final text appeals to a much wider audience.[43] For example, Locke writes: "I place Vertue [sic] as the first and most necessary of those Endowments, that belong to a Man or a Gentleman."[44] James Axtell, who edited the most comprehensive edition of Locke's educational writings, has explained that although "he was writing for this small class, this does not preclude the possibility that many of the things he said about education, especially its main principles, were equally applicable to all children" (Axtell's emphasis).[45] This was a contemporary view as well; Pierre Coste, in his introduction in the first French edition in 1695, wrote, "it is certain that this Work was particularly designed for the education of Gentlemen: but this does not prevent its serving also for the education of all sorts of Children, of whatever class they are."[46]

While it is possible to apply Locke's general principles of education to all children, and contemporaries such as Coste certainly did so, Locke himself, despite statements that may imply the contrary, believed that Some Thoughts applied only to the wealthy and the middle-class (or as they would have been referred to at the time, the "middling sorts"). One of Locke's conclusions in Some Thoughts Concerning Education is that he "think[s] a Prince, a Nobleman, and an ordinary Gentleman's Son, should have different Ways of Breeding."[47] As Peter Gay writes, "[i]t never occurred to him that every child should be educated or that all those to be educated should be educated alike. Locke believed that until the school system was reformed, a gentleman ought to have his son trained at home by a tutor. As for the poor, they do not appear in Locke's little book at all."[48]

In his "Essay on the Poor Law," Locke turns to the education of the poor; he laments that "the children of labouring people are an ordinary burden to the parish, and are usually maintained in idleness, so that their labour also is generally lost to the public till they are 12 or 14 years old."[49] He suggests, therefore, that "working schools" be set up in each parish in England for poor children so that they will be "from infancy [three years old] inured to work."[50] He goes on to outline the economics of these schools, arguing not only that they will be profitable for the parish, but also that they will instill a good work ethic in the children.[51]

Gender

[edit]Locke wrote Some Thoughts Concerning Education in response to his friend Edward Clarke's query on how to educate his son, so the text's "principal aim", as Locke states at the beginning, "is how a young gentleman should be brought up from his infancy." This education "will not so perfectly suit the education of daughters; though where the difference of sex requires different treatment, it will be no hard matter to distinguish" (Locke's emphasis).[25] This passage suggests that, for Locke, education was fundamentally the same for men and women—there were only small, obvious differences for women. This interpretation is supported by a letter he wrote to Mary Clarke in 1685 stating that "since therefore I acknowledge no difference of sex in your mind relating ... to truth, virtue and obedience, I think well to have no thing altered in it from what is [writ for the son]."[52] Martin Simons states that Locke "suggested, both by implication and explicitly, that a boy's education should be along the lines already followed by some girls of the intelligent genteel classes."[53] Rather than sending boys to schools which would ignore their individual needs and teach them little of value, Locke argues that they should be taught at home as girls already were and "should learn useful and necessary crafts of the house and estate."[54] Like his contemporary Mary Astell, Locke believed that women could and should be taught to be rational and virtuous.[55]

But Locke does recommend several minor "restrictions" relating to the treatment of the female body. The most significant is his reining in of female physical activity for the sake of physical appearance: "But since in your girls care is to be taken too of their beauty as much as health will permit, this in them must have some restriction ... 'tis fit their tender skins should be fenced against the busy sunbeams, especially when they are very hot and piercing."[56] Although Locke's statement indicates that he places a greater value on female than male beauty, the fact that these opinions were never published allowed contemporary readers to draw their own conclusions regarding the "different treatments" required for girls and boys, if any.[57] Moreover, compared to other pedagogical theories, such as those in the best-selling conduct book The Whole Duty of a Woman (1696), the female companion to The Whole Duty of Man (1657), and Rousseau's Emile (1762), which both proposed entirely separate educational programs for women, Locke's Some Thoughts appears either more egalitarian, or more unbodied.[original research?]

Reception and legacy

[edit]

Along with Rousseau's Emile (1762), Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education was one of the foundational eighteenth-century texts on educational theory. In Britain, it was considered the standard treatment of the topic for over a century. For this reason, some critics have maintained that Some Thoughts Concerning Education vies with the Essay Concerning Human Understanding for the title of Locke's most influential work. Some of Locke's contemporaries, such as seventeenth-century German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, believed this as well; Leibniz argued that Some Thoughts superseded even the Essay in its impact on European society.[58]

Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education was a runaway best-seller. During the eighteenth century alone, Some Thoughts was published in at least 53 editions: 25 English, 16 French, six Italian, three German, two Dutch, and one Swedish.[59] It was also excerpted in novels such as Samuel Richardson's Pamela (1740–1), and it formed the theoretical basis of much children's literature, particularly that of the first successful children's publisher, John Newbery. According to James A. Secord, an eighteenth-century scholar, Newbery included Locke's educational advice to legitimise the new genre of children's literature. Locke's imprimatur would ensure the genre's success.[60]

By the end of the eighteenth century, Locke's influence on educational thought was widely acknowledged. In 1772 James Whitchurch wrote in his Essay Upon Education that Locke was "an Author, to whom the Learned must ever acknowledge themselves highly indebted, and whose Name can never be mentioned without a secret Veneration, and Respect; his Assertions being the result of intense Thought, strict Enquiry, a clear and penetrating Judgment."[61] Writers as politically dissimilar as Sarah Trimmer, in her periodical The Guardian of Education (1802–06),[62] and Maria Edgeworth, in the educational treatise she penned with her father, Practical Education (1798), invoked Locke's ideas. Even Rousseau, while disputing Locke's central claim that parents should treat their children as rational beings, acknowledged his debt to Locke.[63]

John Cleverley and D. C. Phillips place Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education at the beginning of a tradition of educational theory which they label "environmentalism". In the years following the publication of Locke's work, Etienne Bonnot de Condillac and Claude Adrien Helvétius eagerly adopted the idea that people's minds were shaped through their experiences and thus through their education. Systems of teaching children through their senses proliferated throughout Europe. In Switzerland, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, relying on Locke's theories, developed the concept of the "object lesson". These lessons focused pupils' attention on a particular thing and encouraged them to use all of their senses to explore it and urged them to use precise words to describe it. Used throughout Europe and America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these object lessons, according to one of their practitioners "if well-managed, cultivate Sense-Perception, or Observation, accustom children to express their thoughts in words, increase their available stock of words and of ideas, and by thus storing material for thinking, also prepare the way for more difficult and advanced study."[64]

Such techniques were also integral to Maria Montessori's methods in the twentieth century. According to Cleverley and Phillips, the television show Sesame Street is also "based on Lockean assumptions—its aim has been to give underprivileged children, especially in the inner cities, the simple ideas and basic experiences that their environment normally does not provide."[65] In many ways, despite Locke's continuing influence, as these authors point out, the twentieth century has been dominated by the "nature vs. nurture" debate in a way that Locke's century was not. Locke's optimistic "environmentalism," though qualified in his text, is now no longer just a moral issue – it is also a scientific issue.[66]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1 ed.). London: A.and J. Churchill at the Black Swan in Paternoster-row. 1693. Retrieved 28 July 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Ezell, Margaret J.M. "John Locke's Images of Childhood: Early Eighteenth-Century Responses to Some Thoughts Concerning Education." Eighteenth-Century Studies 17.2 (1983–84), 141.

- ^ Tarcov, Nathan. Locke's Education for Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1984), 80.

- ^ Axtell, James L. "Introduction." The Educational Writings of John Locke. Ed. James L. Axtell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1968), 60.

- ^ Qtd. in Frances A. Yates, "Giodano Bruno's Conflict with Oxford." Journal of the Warburg Institute 2.3 (1939), 230.

- ^ Axtell, 69–87.

- ^ Axtell, 4.

- ^ Mendelson, Sara Heller (27 May 2010). "Clarke [née Jepp], Mary (d. 1705)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/REF:ODNB/66720. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Axtell, 13.

- ^ Axtell, 15–16.

- ^ a b Tarcov, 79.

- ^ Locke, John. Some Thoughts Concerning Education and of the Conduct of the Understanding. Eds. Ruth W. Grant and Nathan Tarcov. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., Inc. (1996), 10; see also Tarcov, 108.

- ^ Ezell, 140.

- ^ Simons, Martin. "Why Can't a Man Be More Like a Woman? (A Note on John Locke's Educational Thought)." Educational Theory 40.1 (1990), 143.

- ^ Yolton, John W. The Two Intellectual Worlds of John Locke: Man Person, and Spirits in the Essay. Ithaca: Cornell University Press (2004), 29–31 and John Yolton, Locke: An Introduction. New York: Basil Blackwell (1985), 19–20; see also Tarcov, 109.

- ^ Yolton, John Locke and Education, 24–5.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 41.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 10.

- ^ Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Ed. Roger Woolhouse. New York: Penguin Books (1997), 357.

- ^ Jolley, 28.

- ^ Tarcov, 83ff and Jolley 28ff.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 11–20.

- ^ Hardyment, Christina. Dream Babies: Child Care from Locke to Spock. London: Jonathan Cape (1983), 226; 246–7; 257–72.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 11.

- ^ a b Locke, Some Thoughts, 12.

- ^ For example, in the "Preface" to A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, Newbery recommended that parents feed their child a "common Diet only, cloath him thin, let him have good Exercise, and be as much exposed to Hardships as his natural Constitution will admit" because "the Face of a child, when it comes into the World, (says the great Mr. Locke) is as tender and susceptible of Injuries as any other Part of the Body; yet by being always exposed, it becomes Proof against the severest Season, and the most inclement Weather." A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, Intended for the Instruction and Amusement of Little Master Tommy, and Pretty Miss Polly. 10th edition. London: Printed for J. Newbery (1760), 6.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 25.

- ^ Yolton, Two Intellectual Worlds, 31–2.

- ^ See, for example, Locke, Essay, 89–91.

- ^ Yolton, Introduction, 22–4.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 34–8.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 34.

- ^ Tarcov, 117–8.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 68.

- ^ Yolton, John Locke and Education, 29–30; Yolton, Two Intellectual Worlds, 34–37; Yolton, Introduction, 36–7.

- ^ Yolton, Introduction, 38.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 195.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 143.

- ^ Bantock, G. H. "'The Under-labourer' in Courtly Clothes: Locke." Studies in the History of Educational Theory: Artifice and Nature, 1350–1765. London: George Allen and Unwin (1980), 241.

- ^ Bantock, 240-2.

- ^ John Dunn, in his influential Political Thought of John Locke, has interpreted this "calling" as a Calvinist religious doctrine. Tarcov has criticized this reading, however, writing: "Dunn’s exposition of the doctrine and its providentialist character is based on Puritan and secondary sources, and he gives no clear evidence for attributing it in this form to Locke." (Tarcov 127)

- ^ Bantock, 244.

- ^ Leites, Edmund. "Locke's Liberal Theory of Parenthood." Ethnicity, Identity, and History. Eds. Joseph B. Maier and Chaim I. Waxman. New Brunswick: Transaction Books (1983), 69–70.

- ^ Locke, Some Thoughts, 102.

- ^ Axtell, 52 and Yolton, John Locke and Education, 30–1.

- ^ Qtd. in Axtell, 52.

- ^ Locke, John (1764). Some thoughts concerning education (13 ed.). London: Printed for A. Millar, H. Woodfall, J. Wiston and B. White ... p. 324.

- ^ Gay, Peter. "Locke on the Education of Paupers." Philosophers on Education: Historical Perspectives. Ed. Amélie Oksenberg Rorty. London: Routledge (1998), 190.

- ^ Locke, John. "An Essay on the Poor Law." Locke: Political Essays. Ed. Mark Goldie. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1997), 190.

- ^ Locke, "Essay on the Poor Law," 190.

- ^ Locke, "An Essay on the Poor Law," 191.

- ^ Locke, John. "Letter to Mrs. Clarke, February 1685." The Educational Writings of John Locke. Ed. James L. Axtell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1968), 344.

- ^ Simons, 135.

- ^ Simons, 140; see also Tarcov, 112.

- ^ Simons, 139 and 143.

- ^ Locke, "Letter to Mrs. Clarke," 344.

- ^ Leites, 69–70.

- ^ Ezell, 147.

- ^ Pickering, Samuel F., Jr. John Locke and Children's Books in Eighteenth-Century England. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press (1981), 10; See Axtell 100–104 for a complete list of editions.

- ^ Secord, James A. "Newton in the Nursery: Tom Telescope and the Philosophy of Tops and Balls, 1761–1838." History of Science 23 (1985), 132–3.

- ^ Qtd. in Pickering, 12.

- ^ Trimmer, Sarah. The Guardian of Education. Bristol: Thoemmes Press (2002), 1:8–9, 108; 2:186–7; 4:74–5.

- ^ See, for example, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile, or on Education. Trans. Allan Bloom. New York: Basic Books (1979), 47 and 107–25.

- ^ Qtd. in John Cleverley and D.C. Phillips, Visions of Childhood: Influential Models from Locke to Spock. New York: Teachers College (1986), 21.

- ^ Cleverley and Phillips, 26.

- ^ Cleverley and Phillips, Chapter 2.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bantock, G. H. "'The Under-labourer' in Courtly Clothes: Locke." Studies in the History of Educational Theory: Artifice and Nature, 1350–1765. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1980. ISBN 0-04-370092-6.

- Brown, Gillian. The Consent of the Governed: The Lockean Legacy in Early American Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-674-00298-9.

- Brown, Gillian. "Lockean Pediatrics." Annals of Scholarship 14.3/15.1 (2000–1): 11–17.

- Chambliss, J. J. "John Locke and Isaac Watts: Understanding as Conduct." Educational Theory as Theory of Conduct: From Aristotle to Dewey. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987. ISBN 0-88706-463-9.

- Chappell, Vere, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-38772-8.

- Cleverley, John and D. C. Phillips. Visions of Childhood: Influential Models from Locke to Spock. New York: Teachers College, 1986. ISBN 0-8077-2800-4.

- Ezell, Margaret J. M. "John Locke’s Images of Childhood: Early Eighteenth Century Responses to Some Thoughts Concerning Education." Eighteenth-Century Studies 17.2 (1983–84): 139–55.

- Ferguson, Frances. "Reading Morals: Locke and Rousseau on Education and Inequality." Representations 6 (1984): 66–84.

- Gay, Peter. "Locke on the Education of Paupers." Philosophers on Education: Historical Perspectives. Ed. Amélie Oksenberg Rorty. London: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0-415-19130-0.

- Leites, Edmund. "Locke's Liberal Theory of Parenthood." Ethnicity, Identity, and History. Eds. Joseph B. Maier and Chaim I. Waxman. New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1983. ISBN 0-87855-461-0.

- Locke, John. The Educational Writings of John Locke. Ed. James L. Axtell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968. ISBN 0-5210-4073-6.

- Pickering, Samuel F., Jr. John Locke and Children’s Books in Eighteenth-Century England. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1981. ISBN 0-87049-290-X.

- Sahakian, William S. and Mabel Lewis. John Locke. Boston: Twayne, 1975. ISBN 0-8057-3539-9.

- Simons, Martin. "What Can't a Man Be More Like a Woman? (A Note on John Locke's Educational Thought)" Educational Theory 40.1 (1990): 135–145.

- Tarcov, Nathan. Locke's Education for Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. ISBN 0-226-78972-1.

- Yolton, John. John Locke and Education. New York: Random House, 1971. ISBN 0-394-31032-2.

- Yolton, John. "Locke: Education for Virtue." Philosophers on Education: Historical Perspectives. Ed. Amélie Oksenberg Rorty. London: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0-415-19130-0.

External links

[edit] Works related to Some Thoughts Concerning Education at Wikisource

Works related to Some Thoughts Concerning Education at Wikisource- Some Thoughts Concerning Education at Standard Ebooks

- Free full text of Some Thoughts Concerning Education at Bartleby.com

- First edition of Some Thoughts Concerning Education at Internet Archive

- John Locke at Project Gutenberg