Khedivate of Egypt

Khedivate of Egypt الْخُدَيْوِيَّةُ الْمِصْرِيَّةُ (Arabic) Al-khudaywiyyah al-misriyyah خدیویت مصر (Ottoman Turkish) Hıdiviyet-i Mısır | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1867–1914 | |||||||||||||||

| Anthem: (1871–1914) Salam Affandina | |||||||||||||||

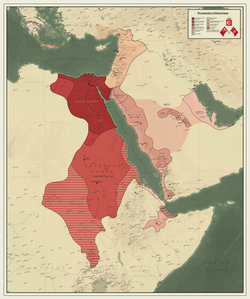

Egypt and its expansion in the 19th century. | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Autonomous vassal of the Ottoman Empire, de facto independent and sovereign state (1867–1914) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Cairo | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, Albanian, Greek,[1] French, English[a] | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam, Coptic Christianity | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Khedive | |||||||||||||||

• 1867–1879 | Isma'il Pasha | ||||||||||||||

• 1879–1892 | Tewfik Pasha | ||||||||||||||

• 1892–1914 | Abbas II | ||||||||||||||

| British Consul-General | |||||||||||||||

• 1883–1907 | Evelyn Baring | ||||||||||||||

• 1907–1911 | Eldon Gorst | ||||||||||||||

• 1911–1914 | Herbert Kitchener | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||

• 1878–1879 (first) | Nubar Pasha | ||||||||||||||

• 1914 (last) | Hussein Roshdy Pasha | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Scramble for Africa | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 8 June 1867 | ||||||||||||||

• Suez Canal opened | 17 November 1869 | ||||||||||||||

| 1881–1882 | |||||||||||||||

• British invasion in the Anglo-Egyptian War | July – September 1882 | ||||||||||||||

| 18 January 1899 | |||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 19 December 1914 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

• Total | 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1882[b] | 6,805,000 | ||||||||||||||

• 1897[b] | 9,715,000 | ||||||||||||||

• 1907[b] | 11,287,000 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Egyptian pound | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| History of Egypt |

|---|

|

|

|

The Khedivate of Egypt (Arabic: الْخُدَيْوِيَّةُ الْمِصْرِيَّةُ or خُدَيْوِيَّةُ مِصْرَ, Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [xedeˈwejjet mɑsˤɾ]; Ottoman Turkish: خدیویت مصر Hıdiviyet-i Mısır) was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brought an end to the short-lived French occupation of Lower Egypt. The Khedivate of Egypt had also expanded to control present-day Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, northwestern Somalia, northeastern Ethiopia, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Syria, Greece, Cyprus, southern and central Turkey, in addition to parts from Libya, Chad, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda, as well as northwestern Saudi Arabia, parts of Yemen and the Kingdom of Hejaz.[5][6]

The United Kingdom invaded and took control in 1882. In 1914, the Ottoman Empire connection was ended and Britain established a protectorate called the Sultanate of Egypt.

History

[edit]Rise of Muhammad Ali

[edit]Upon the conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate by the Ottoman Empire in 1517, the country was governed as an Ottoman province. The Ottoman Porte (government) was content to permit local rule to remain in the hands of the Mamluks, the Egyptian military led by Circassian-Turkic leaders who had held power in Egypt since the 13th century. Save for military expeditions to crush Mamluk uprisings seeking to reestablish the independent Egyptian sultanate, the Ottomans largely ignored Egyptian affairs until the French campaign in Egypt and Syria in 1798.

Between 1799 and 1801, the Porte, working at times with France's main enemy, Great Britain, undertook various campaigns to restore Ottoman rule in Egypt. By August 1801, the remaining French forces of General Jacques-François Menou withdrew from Egypt.

The period between 1801 and 1805 was, effectively, a three-way civil war in Egypt between the Egyptian Mamluks, the Ottoman Turks, and Albanian troops the Ottoman Porte dispatched from Rumelia (the Empire's European province), under the command of Muhammad Ali Pasha, to restore the Empire's authority.

Following the defeat of the French, the Porte assigned Koca Hüsrev Mehmed Pasha as the new Wāli (governor) of Egypt, tasking him to kill or imprison the surviving Egyptian Mamluk beys. Many of these were freed by or fled with the British, while others held Minya between Upper and Lower Egypt.

Amid these disturbances, Koca Hüsrev Mehmed Pasha attempted to disband his Albanian bashi-bazouks (soldiers) without pay. This led to rioting that drove Koca Hüsrev Mehmed Pasha from Cairo. During the ensuing turmoil, the Porte sent Muhammad Ali Pasha to Egypt.

However, Muhammad Ali seized control of Egypt, declared himself ruler and quickly consolidated an independent local power base. After repeated failed attempts to remove and kill him, in 1805 the Porte officially recognised Muhammad Ali as Wāli of Egypt. Demonstrating his grander ambitions, Muhammad Ali Pasha claimed for himself the higher title of Khedive (Viceroy), ruling the self-proclaimed (but not recognised) Khedivate of Egypt. He murdered the remaining Mamluk beys in 1811, solidifying his control of Egypt. He is regarded as the founder of modern Egypt because of the dramatic reforms he instituted in the military, agricultural, economic and cultural spheres.

Reforms

[edit]During Muhammad Ali's absence in Arabia his representative at Cairo had completed the confiscation, begun in 1808, of almost all the lands belonging to private individuals, who were forced to accept instead inadequate pensions. By this revolutionary method of land nationalization Muhammad Ali became proprietor of nearly all the soil of Egypt, an iniquitous measure against which the Egyptians had no remedy.

The pasha also attempted to reorganize his troops on European lines, but this led to a formidable mutiny in Cairo. Muhammad Ali's life was endangered, and he sought refuge by night in the citadel, while the soldiery committed many acts of plunder. The revolt was reduced by gifts to the chiefs of the insurgents, and Muhammad Ali ordered compensation from the treasury for those who had suffered in the disturbances. The Nizam-i Cedid (New System) project was, in consequence of this mutiny, abandoned for a time.

While Ibrahim was engaged in the second Arabian campaign the pasha turned his attention to strengthening the Egyptian economy. He created state monopolies over the chief products of the country. He set up factories and began digging in 1819 a new canal to Alexandria called the Mahmudiyya after the sultan. The old canal had long fallen into decay and the necessity of a safe channel between Alexandria and the Nile was much felt. The conclusion in 1838 of a commercial treaty with Turkey, negotiated by Henry Bulwer, struck a death blow to the system of monopolies, though the application of the treaty to Egypt was delayed for some years.

Another notable fact in the economic progress of the country was the development of the cultivation of cotton in the Delta in 1822 and onwards. The cotton grown had been brought from the Turco-Egyptian Sudan by Maho Bey and the organization of the new industry from which in a few years Muhammad Ali was enabled to extract considerable revenues.

Efforts were made to promote education and the study of medicine. To European merchants, on whom he was dependent for the sale of his exports, Muhammad Ali showed much favor and under his influence, the port of Alexandria again rose into importance. It was also under Muhammad Ali's encouragement that the overland transit of goods from Europe to India via Egypt was resumed.

Invasion of Libya and Sudan

[edit]In 1820, Muhammad Ali gave orders to commence the conquest of Ottoman Tripolitania. He first sent an expedition westward in February, which conquered and annexed the Siwa Oasis. Ali's intentions for Sudan were to extend his rule southward, capture the valuable caravan trade bound for the Red Sea, and secure the rich gold mines which he believed to exist in Sennar. He also saw in the campaign a means of getting rid of his disaffected troops, and of obtaining a sufficient number of captives to form the nucleus of the new army.

The forces destined for this service were led by Ismail, the youngest son of Muhammad Ali. They consisted of between 4000 and 5000 men, being Albanians, Turks and Egyptians. They left Cairo in July 1820. The Funj Sultanate of Nubia submitted without a fight; the Shaigiya Confederation immediately beyond the province of Dongola were defeated; the remnant of the Mamluks dispersed; and Sennar was reduced without a battle.

Muhammad Bey, the defterdar, with another force of about the same strength, was then sent by Muhammad Ali against Kordofan with like result, but not without a hard-fought engagement. In October 1822, Ismaʿil, with his retinue, was burnt to death by Nimr, the makk (king) of Shendi. The defterdar, a man infamous for his cruelty, assumed the command of those provinces and exacted terrible retribution from the inhabitants. Khartoum was founded at this time, and in the following years, Egyptian rule was greatly extended and control of the Red Sea ports of Suakin and Massawa obtained.

Greek campaign

[edit]Muhammad Ali understood that the empire he had so laboriously built up might at any time have to be defended by force of arms against his master Sultan Mahmud II, whose whole policy had been directed to curbing the power of too-ambitious vassals, and who was under the influence of the personal enemies of the pasha of Egypt, notably Koca Hüsrev Mehmed Pasha, the grand vizier, who had never forgiven his humiliation in Egypt in 1803.

Mahmud also was already planning reforms borrowed from the West, and Muhammad Ali, who had had plenty of opportunity of observing the superiority of European methods of warfare, was determined to anticipate the sultan in the creation of a fleet and an army on European lines, partly as a precaution, partly as an instrument for the realization of yet wider schemes of ambition. Before the outbreak of the War of Greek Independence in 1821, he had already expended much time and energy in organizing a fleet and in training, under the supervision of French instructors, native officers and artificers; though it was not till 1829 that the opening of a dockyard and arsenal at Alexandria enabled him to build and equip his own vessels. By 1823, moreover, he had succeeded in carrying out the reorganization of his army on European lines, the turbulent Turkish and Albanian elements being replaced by Sudanese and fellahin. The effectiveness of the new force was demonstrated in the suppression of an 1823 revolt of the Albanians in Cairo by six disciplined Sudanese regiments; after which Mehemet Ali was no more troubled with military mutinies.

His foresight was rewarded by the invitation of the sultan to help him in the task of subduing the Greek insurgents, offering as reward the pashaliks of the Morea and of Syria. Muhammad Ali had already, in 1821, been appointed by him governor of Crete, which he had occupied with a small Egyptian force. In the autumn of 1824, a fleet of 60 Egyptian warships carrying a large force of 17,000 disciplined troops concentrated in Suda Bay, and, in the following March, with Ibrahin as commander-in-chief landed in the Morea.

His naval superiority wrested from the Greeks the command of a great deal of the sea, on which the fate of the insurrection ultimately depended, while on land the Greek irregular bands, having largely soundly beaten the Porte's troops, had finally met a worthy foe in Ibrahim's disciplined troops. The history of the events that led up to the battle of Navarino and the liberation of Greece is told elsewhere; the withdrawal of the Egyptians from the Morea was ultimately due to the action of Admiral Sir Edward Codrington, who early in August 1828 appeared before Alexandria and induced the pasha, by no means sorry to have a reasonable excuse, by a threat of bombardment, to sign a convention undertaking to recall Ibrahim and his army. But for the action of European powers, it is suspected by many that the Ottoman Empire might have defeated the Greeks.

Wars against the Turks

[edit]Although Muhammad Ali had only been granted the title of wali, he proclaimed himself khedive, or hereditary viceroy, early on during his rule. The Ottoman government, although irritated, did nothing until Muhammad Ali invaded Ottoman-ruled Syria in 1831. The governorship of Syria had been promised to him by the sultan, Mahmud II, for his assistance during the Greek War of Independence, but the title was not granted to him after the war.[7] This caused the Ottomans, allied with the British, to counter-attack in 1839.

In 1840, the British bombarded Beirut and an Anglo-Ottoman force landed and seized Acre.[8] The Egyptian army was forced to retreat back home, and Syria again became an Ottoman province. As a result of the Convention of London (1840), Muhammad Ali gave up all conquered lands with the exception of the Sudan and was, in turn, granted the hereditary governorship of the Sudan.

Muhammad Ali's successors

[edit]By 1848, Muhammad Ali was old and senile enough for his tuberculosis-ridden son, Ibrahim, to demand his accession to the governorship. The Ottoman sultan acceded to the demands, and Muhammad Ali was removed from power. However, Ibrahim died of his disease months later, outlived by his father, who died in 1849.

Ibrahim was succeeded by his nephew Abbas I, who undid many of Muhammad Ali's accomplishments. Abbas was assassinated by two of his slaves in 1854, and Muhammad Ali's fourth son, Sa'id, succeeded him. Sa'id brought back many of his father's policies[9] but otherwise had an unremarkable reign. Ismail Pasha replaced Turkish with Arabic as the administrative and elite language, further reducing Turkish influence in Egypt and enhancing Egypt’s modernization and independence.

Invasion of East Africa

[edit]In the early 19th сentury the Egyptians tried multiple attempts to take full control of the Nile River and with that take control of the Horn of Africa which was a Key route to enter the Southern Arabian peninsula. After failing multiple times to take control of the Bogos/Hamassien however these attempted invasions were repelled by the emperor at the time Tewedros.

Sa'id ruled for only nine years,[10] and his nephew Isma'il, another grandson of Muhammad Ali, became wali. In 1866 the polity occupied the Emirate of Harar. In 1867, the Ottoman sultan acknowledged Isma'il's use of the title khedive. In 1874, Ismail Pasha ordered the deputation of warships to patrol Tadjoura whereafter for ten years, the Khedivate was established from Zeila to Berbera, until their withdrawal in April 1884 and failed attempts to establish themselves beyond Berbera and the eastern littoral of Somalia.[11]

War with Ethiopia

[edit]Ismail dreamt of expanding his realm across the entire Nile including its diverse sources, and over the whole African coast of the Red Sea.[12] This, together with rumours about rich raw material and fertile soil, led Ismail to expansive policies directed against the Ethiopian Empire under Yohannes IV. In 1865, the Ottoman Sublime Porte ceded Habesh Eyalet to Isma'il, with Massawa and Suakin at the Red Sea as the main cities of that province. This province, which neighboured Ethiopia, first consisted of a coastal strip but expanded subsequently inland into territory controlled by the Ethiopian emperor. Here Ismail occupied regions originally claimed by the Ottomans when they had established the Habesh Eyalet in the 16th century.

New economically promising projects, like huge cotton plantations in the Barka delta, were started. In 1872, Bogos (with the city of Keren) was annexed by the governor of the new "Province of Eastern Sudan and the Red Sea Coast", Werner Munzinger Pasha. In October 1875 Ismail's army tried to occupy the adjacent highlands of Hamasien, which were then tributary to the Ethiopian Emperor, and suffered defeat at the Battle of Gundet.

In March 1876, Ismail's army tried again and suffered a second dramatic defeat by Yohannes' army in the Battle of Gura. Ismail's son Hassan was captured by the Ethiopians and only released after a large ransom. This was followed by a long cold war, only finishing in 1884 with the Anglo-Egyptian-Ethiopian Hewett Treaty, when Bogos was given back to Ethiopia. The Red Sea Province created by Ismail and his governor Munzinger Pasha was taken over by the Kingdom of Italy shortly thereafter and became the territorial basis for the Colony of Eritrea (proclaimed in 1890).

British occupation

[edit]In 1882 opposition to European control led to growing tension amongst native notables, the most dangerous opposition coming from the army. A large military demonstration in September 1881 forced the Khedive Tewfiq to dismiss his Prime Minister. In April 1882 France and Great Britain sent warships to Alexandria to bolster the Khedive amidst a turbulent climate, spreading fear of invasion throughout the country. By June Egypt was in the hands of nationalists opposed to European domination of the country. A British naval bombardment of Alexandria had little effect on the opposition which led to the landing of a British expeditionary force at both ends of the Suez Canal in August 1882. The British succeeded in defeating the Egyptian Army at Tel El Kebir in September and took control of the country putting Tewfiq back in control. The purpose of the invasion had been to restore political stability to Egypt under a government of the Khedive and international controls which were in place to streamline Egyptian financing since 1876.

Egyptian Fundamental Ordinance of 1882, a constitution, followed an abortive attempt to promulgate a constitution in 1879. The document was limited in scope and was effectively more of an organic law of the Consultative Council to the khedive than an actual constitution.[13]

British occupation ended nominally with the deposition of the last khedive Abbas II on 5 November 1914[14] and the establishment of a British protectorate, with the installation of sultan Hussein Kamel on 19 December 1914.

Sanctioned khedival rule (1867–1914)

[edit]European influence

[edit]By Isma'il's reign, the Egyptian government, headed by the minister Nubar Pasha, had become dependent on Britain and France for a healthy economy. Isma'il attempted to end this European dominance, while at the same time pursuing an aggressive domestic policy. Under Isma'il, 112 canals and 400 bridges were built in Egypt.[15]

Because of his efforts to gain economic independence from the European powers, Isma'il became unpopular with many British and French diplomats, including Evelyn Baring and Alfred Milner, who claimed that he was "ruining Egypt."[15]

In 1869, the completion of the Suez Canal gave Britain a faster route to India. This made Egypt increasingly reliant on Britain for both military and economic aid. Isma'il made no effort to reconcile with the European powers, who pressured the Ottoman sultan into removing him from power.[16]

Tewfik and the loss of Sudan

[edit]Isma'il was succeeded by his eldest son Tewfik, who, unlike his younger brothers, had not been educated in Europe. He pursued a policy of closer relations with Britain and France but his authority was undermined in a rebellion led by his war minister, Urabi Pasha, in 1882. Urabi took advantage of violent riots in Alexandria to seize control of the government and temporarily depose Tewfik.

British naval forces shelled and captured Alexandria, and an expeditionary force under General Sir Garnet Wolseley was formed in England. The British army landed in Egypt soon afterwards and defeated Urabi's army in the Battle of Tel el-Kebir. Urabi was tried for treason and sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to exile. After the revolt, the Egyptian army was reorganized on a British model and commanded by British officers.

Meanwhile, a religious rebellion had broken out in the Sudan, led by Muhammad Ahmed, who proclaimed himself the Mahdi. The Mahdist rebels had seized the regional capital of Kordofan and annihilated two British-led expeditions sent to quell it.[17] The British soldier-adventurer Charles George Gordon, an ex-governor of the Sudan, was sent to the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, with orders to evacuate its minority of European and Egyptian inhabitants. Instead of evacuating the city, Gordon prepared for a siege and held out from 1884 to 1885. However, Khartoum eventually fell, and he was killed.[17]

The British Gordon Relief Expedition was delayed by several battles and was thus unable to reach Khartoum and save Gordon. The fall of Khartoum resulted in the proclamation of an Islamic state, ruled over first by the Mahdi and then by his successor Khalifa Abdullahi.

Reconquest of the Sudan

[edit]In 1896, during the reign of Tewfik's son, Abbas II, a massive Anglo-Egyptian force, under the command of General Herbert Kitchener, began the conquest of the Sudan not long after the death of the Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad, to typhus.[18] The Mahdists were defeated in the battles of Abu Hamed and Atbara. The campaign was concluded with the Anglo-Egyptian victory in the Battle of Omdurman, the Mahdist capital.

Caliph Abdallahi ibn Muhammad was hunted down and killed in 1899 in the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat, and Anglo-Egyptian rule was restored to the Sudan.

End of the Khedivate

[edit]Abbas II became very hostile to the British as his reign drew on, and, by 1911, was considered by Lord Kitchener to be a "wicked little Khedive" worthy of deposition.

In 1914, when World War I broke out, the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers against Britain and France. Britain now removed the nominal role of Constantinople, proclaimed a Sultanate of Egypt and abolished the Khedivate on 5 November 1914.[14] Abbas II, who supported the Central Powers and was in Vienna for a state visit, was deposed from the Khedivate throne in his absence by the enforcement of the British military authorities in Cairo and was banned from returning to Egypt. He was succeeded by his uncle Hussein Kamel, who took the title of Sultan on 19 December 1914.

Economy

[edit]Currency

[edit]During the khedivate, the standard form of Egyptian currency was the Egyptian pound. Because of the gradual European domination of the Egyptian economy, the khedivate adopted the gold standard in 1885.[19]

Adoption of European-style industries

[edit]Although the adoption of modern, Western industrial techniques was begun under Muhammad Ali in the early 19th century, the policy was continued under the khedives.[20]

Machines were imported into Egypt and by the abolition of the khedivate in 1914, the textile industry had become the most prominent one in the nation.

Military

[edit]In 1877 the Egyptian military contained:[21]

- 58 infantry battalions (organised into 18 regiments and 4 independent battalions)

- 10 independent Nubian Rifle companies

- 24 Cavalry squadrons (organised into 4 regiments)

- 1 Sapper battalion

- 24 field artillery batteries (organised into 2 regiments) with 144 guns primarily of the La Hitte system

- 3 regiments of Fortress artillery with 276 guns

This amounted to 58,000 troops in the regular army; there were also 5,000 military and municipal police and various other irregular formations.[21]

Notable events and people during khedival rule

[edit]Events

[edit]- Greek War of Independence (1821–1829)

- Egyptian invasion of Syria (1831)

- Oriental Crisis of 1840 (1840)

- Crimean War

- 2nd Franco-Mexican War

- Cretan Revolt

- Serbian–Ottoman Wars (1876–1878)

- Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

- Completion of the Suez Canal (1869)

- Urabi revolt (1881)

- First Mahdist War (1881–1885)

- Second Mahdist War (1896–1899)

- Abolishment of the khedivate; establishment of the Sultanate of Egypt (1914)

People

[edit]- Muhammad Ali: First hereditary Ottoman governor of Egypt

- Ibrahim: Muhammad Ali's son and successor (in 1848)

- Abbas I: Ibrahim's successor

- Sa'id: Abbas' successor

- Isma'il: First khedive of Egypt; Sa'id's successor

- Tewfik: Second khedive; Isma'il's successor

- Abbas II of Egypt: Third and last khedive; Tewfik's successor

- Hussein Kamel: Isma'il's son; first Sultan of Egypt

- Nubar Pasha: Egyptian politician; often prime minister of Egypt

- Ahmed Urabi: Egyptian soldier, war minister; leader of the Urabi revolt

- Muhammad Ahmed: Self-proclaimed Mahdi; leader of the Sudanese Mahdist rebellion

List of Khedives

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu (2012). "Turks in the Egyptian Administration and the Turkish Language as a Language of Administration". In Humphrey Davies (ed.). The Turks in Egypt and their Cultural Legacy. Oxford Academic. pp. 81–98. doi:10.5743/cairo/9789774163975.003.0005. ISBN 9789774163975.

- ^ Holes, Clive (2004). Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions, and Varieties. Georgetown Classics in Arabic Language and Linguistics (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-58901-022-2. OCLC 54677538. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ Bonné, Alfred (2003) [First published 1945]. The Economic Development of the Middle East: An Outline of Planned Reconstruction after the War. The International Library of Sociology. London: Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-415-17525-8. OCLC 39915162. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Tanada, Hirofumi (March 1998). "Demographic Change in Rural Egypt, 1882–1917: Population of Mudiriya, Markaz and Madina". Discussion Paper. No. D97–22. Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University. hdl:10086/14678.

- ^ "حدود مصر في عهد الخديوي إسماعيل – خرائط". elnabaa. 21 December 2016.

- ^ "خرائط نادرة لحدود مصر الخديوية". toraseyat. 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Private Tutor". Infoplease.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Egypt – Muhammad Ali, 1805–48". Country-data.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Egypt – Abbas Hilmi I, 1848–54 and Said, 1854–63". Country-data.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Khedive of Egypt Ismail". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "FRENCH SOMALI COAST 1708 – 1946 FRENCH SOMALI COAST | Awdalpress.com". www.awdalpress.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Moslem Egypt and Christian Abyssinia; Or, Military Service Under the Khedive, in his Provinces and Beyond their Borders, as Experienced by the American Staff". World Digital Library. 1880. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Aslı Ü. Bâli and Hanna Lerner. Constitution Writing, Religion and Democracy. Cambridge University Press, 2017. p. 293. ISBN 9781107070516

- ^ a b Article 17 of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) regarding the new status of Egypt and Sudan, starting from 5 November 1914, when the Khedivate was abolished.

- ^ a b "Egypt – From Autonomy To Occupation: Ismail, Tawfiq, And The Urabi Revolt". Country-data.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "BBC – History – British History in depth: The Suez Crisis". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Heritage History – Putting the "Story" back into History". Heritage-history.com. 10 January 1904. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Britain Sudan Reconquest 1896–1899". Onwar.com. 16 December 2000. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Egyptian Pound". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Cain, P. J. (6 July 2010). "Character and imperialism: The british financial administration of Egypt, 1878–1914". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 34 (2): 177–200. doi:10.1080/03086530600633405. S2CID 145334112. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b Olender, Piotr (2017). Russo-Turkish Naval War 1877-1878. [Place of publication not identified]. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-83-65281-66-1. OCLC 992804901.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Berridge, W. J. "Imperialist and Nationalist Voices in the Struggle for Egyptian independence, 1919–22." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42.3 (2014): 420–439.

- Botman, Selma. Egypt from Independence to Revolution, 1919–1952 (Syracuse UP, 1991).

- Cain, Peter J. "Character and imperialism: the British financial administration of Egypt, 1878–1914." Journal of imperial and Commonwealth history 34.2 (2006): 177–200.

- Cain, Peter J. "Character,'Ordered Liberty', and the Mission to Civilise: British Moral Justification of Empire, 1870–1914." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 40.4 (2012): 557–578.

- Cole, Juan R.I. Colonialism and Revolution in the Middle East: The Social and Cultural Origins of Egypt's 'Urabi Revolt (Princeton UP, 1993.)

- Daly, M.W. The Cambridge History of Egypt Volume 2 Modern Egypt, from 1517 to the end of the twentieth century (1998) pp 217–84 on 1879–1923. online

- Dunn, John P. Khedive Ismail's Army (2013)

- EzzelArab, AbdelAziz. "The experiment of Sharif Pasha's cabinet (1879): An inquiry into the historiography of Egypt's elite movement." International Journal of Middle East Studies 36.4 (2004): 561–589.

- Fahmy, Ziad. "Media Capitalism: Colloquial Mass Culture and Nationalism in Egypt, 1908–1918", International Journal of Middle East Studies 42#1 (2010), 83–103.

- Goldberg, Ellis. "Peasants in Revolt – Egypt 1919", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 24 (1992), 261–80.

- Goldschmidt, Jr., Arthur, ed. Biographical Dictionary of Modern Egypt (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1999).

- Goldschmidt, Jr., Arthur. ed. Historical Dictionary of Egypt (Scarecrow Press, 1994).

- Harrison, Robert T. Gladstone's Imperialism in Egypt: Techniques of Domination (1995).

- Hicks, Geoffrey. "Disraeli, Derby and the Suez Canal, 1875: some myths reassessed." History 97.326 (2012): 182–203.

- Hopkins, Anthony G. "The Victorians and Africa: a reconsideration of the occupation of Egypt, 1882." Journal of African History 27.2 (1986): 363–391. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/181140 online

- Hunter, F. Robert. "State‐society relations in nineteenth‐century Egypt: the years of transition, 1848–79." Middle Eastern Studies 36.3 (2000): 145–159.

- Hunter. F. Robert. Egypt Under the Khedives: 1805–1879: From Household Government to Modern Bureaucracy (2nd ed. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1999.)

- Langer, William, L. European Alliances and Alignments: 1871–1890 (2nd ed. 1956) pp 251–80. online

- Marlowe, John. Cromer in Egypt (Praeger, 1970.)

- Owen, Roger. Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul (Oxford UP, 2004.)

- Pinfari, Marco. "The Unmaking of a Patriot: Anti-Arab Prejudice in the British Attitude towards the Urabi Revolt (1882)." Arab Studies Quarterly 34.2 (2012): 92–108. online

- Robinson, Ronald, and John Gallagher. Africa and the Victorians: The Climax of Imperialism (1961) pp 76–159. online

- Sayyid-Marsot, Afaf Lutfi. Egypt and Cromer; a Study in Anglo-Egyptian Relations (Praeger, 1969).

- Scholch, Alexander. Egypt for the Egyptians!: the Socio-Political Crisis in Egypt, 1878–1882 (London: Ithaca Press, 1981.)

- Shock, Maurice. "Gladstone's Invasion of Egypt, 1882" History Today (June 1957) 7#6 pp 351–357.

- Tassin, Kristin Shawn. "Egyptian nationalism, 1882–1919: elite competition, transnational networks, empire, and independence" (PhD Dissertation, U of Texas, 2014.) online; bibliography pp 269–92.

- Tignor, Robert L. Modernization and British colonial rule in Egypt, 1882–1914 (Princeton UP, 2015).

- Tucker, Judith E. Women in nineteenth-century Egypt (Cambridge UP, 1985).

- Ulrichsen, Kristian Coates. The First World War in the Middle East (Hurst, 2014).

- Walker, Dennis. "Mustafa Kamil's Party: Islam, Pan-Islamism, and Nationalism", Islam in the Modern Age, Vol. 11 (1980), 230–9 and Vol. 12 (1981), 1–43

Primary sources

[edit]- Cromer, Earl of. Modern Egypt (2 vol 1908) online free 1220pp

- Milner, Alfred. England in Egypt (London, 1892). online

- Amira Sonbol, ed. The Last Khedive of Egypt: Memoirs of Abbas Hilmi II (Reading, UK: Ithaca Press, 1998).

- States and territories established in 1867

- States and territories disestablished in 1914

- 19th century in Egypt

- 20th century in Egypt

- British colonisation in Africa

- Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty

- Former countries in West Asia

- Former British protectorates

- Former British colonies and protectorates in Africa

- History of Egypt (1900–present)

- New Imperialism

- Ottoman Egypt

- 1867 establishments in Africa

- 1914 disestablishments in Africa

- 1860s establishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 1880s establishments in the British Empire

- 20th-century disestablishments in Egypt

- Vassal states of the Ottoman Empire