Social norm

A social norm is a shared standard of acceptable behavior by a group.[1] Social norms can both be informal understandings that govern the behavior of members of a society, as well as be codified into rules and laws.[2] Social normative influences or social norms, are deemed to be powerful drivers of human behavioural changes and well organized and incorporated by major theories which explain human behaviour.[3] Institutions are composed of multiple norms. Norms are shared social beliefs about behavior; thus, they are distinct from "ideas", "attitudes", and "values", which can be held privately, and which do not necessarily concern behavior.[4] Norms are contingent on context, social group, and historical circumstances.[5]

Scholars distinguish between regulative norms (which constrain behavior), constitutive norms (which shape interests), and prescriptive norms (which prescribe what actors ought to do).[6][7][3] The effects of norms can be determined by a logic of appropriateness and logic of consequences; the former entails that actors follow norms because it is socially appropriate, and the latter entails that actors follow norms because of cost-benefit calculations.[8]

Three stages have been identified in the life cycle of a norm: (1) Norm emergence – norm entrepreneurs seek to persuade others of the desirability and appropriateness of certain behaviors; (2) Norm cascade – when a norm obtains broad acceptance; and (3) Norm internalization – when a norm acquires a "taken-for-granted" quality.[7] Norms are robust to various degrees: some norms are often violated whereas other norms are so deeply internalized that norm violations are infrequent.[4][3] Evidence for the existence of norms can be detected in the patterns of behavior within groups, as well as the articulation of norms in group discourse.[4]

In some societies, individuals often limit their potential due to social norms, while others engage in social movements to challenge and resist these constraints.

Definition

[edit]

There are varied definitions of social norms, but there is agreement among scholars that norms are:[9]

- social and shared among members of a group,

- related to behaviors and shape decision-making,

- proscriptive or prescriptive

- socially acceptable way of living by a group of people in a society.

In 1965, Jack P. Gibbs identified three basic normative dimensions that all concepts of norms could be subsumed under:

- "a collective evaluation of behavior in terms of what it ought to be"

- "a collective expectation as to what behavior will be"

- "particular reactions to behavior" (including attempts sanction or induce certain conduct)[10]

According to Ronald Jepperson, Peter Katzenstein and Alexander Wendt, "norms are collective expectations about proper behavior for a given identity."[11] Wayne Sandholtz argues against this definition, as he writes that shared expectations are an effect of norms, not an intrinsic quality of norms.[12] Sandholtz, Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink define norms instead as "standards of appropriate behavior for actors with a given identity."[12][7] In this definition, norms have an "oughtness" quality to them.[12][7]

Michael Hechter and Karl-Dieter Opp define norms as "cultural phenomena that prescribe and proscribe behavior in specific circumstances."[13] Sociologists Christine Horne and Stefanie Mollborn define norms as "group-level evaluations of behavior."[14] This entails that norms are widespread expectations of social approval or disapproval of behavior.[14] Scholars debate whether social norms are individual constructs or collective constructs.[9]

Economist and game theorist Peyton Young defines norms as "patterns of behavior that are self-enforcing within a group."[5] He emphasizes that norms are driven by shared expectations: "Everyone conforms, everyone is expected to conform, and everyone wants to conform when they expect everyone else to conform."[5] He characterizes norms as devices that "coordinate people's expectations in interactions that possess multiple equilibria."[15]

Concepts such as "conventions", "customs", "morals", "mores", "rules", and "laws" have been characterized as equivalent to norms.[10] Institutions can be considered collections or clusters of multiple norms.[7] Rules and norms are not necessarily distinct phenomena: both are standards of conduct that can have varying levels of specificity and formality.[12][14] Laws are a highly formal version of norms.[16][12][17] Laws, rules and norms may be at odds; for example, a law may prohibit something but norms still allow it.[14] Norms are not the equivalent of an aggregation of individual attitudes.[18] Ideas, attitudes and values are not necessarily norms, as these concepts do not necessarily concern behavior and may be held privately.[4][14] "Prevalent behaviors" and behavioral regularities are not necessarily norms.[14][9] Instinctual or biological reactions, personal tastes, and personal habits are not necessarily norms.[9]

Emergence and transmission

[edit]Groups may adopt norms in a variety of ways.

Some stable and self-reinforcing norms may emerge spontaneously without conscious human design.[19][13] Peyton Young goes as far as to say that "norms typically evolve without top-down direction... through interactions of individuals rather than by design."[5] Norms may develop informally, emerging gradually as a result of repeated use of discretionary stimuli to control behavior.[20][21] Not necessarily laws set in writing, informal norms represent generally accepted and widely sanctioned routines that people follow in everyday life.[22] These informal norms, if broken, may not invite formal legal punishments or sanctions, but instead encourage reprimands, warnings, or othering; incest, for example, is generally thought of as wrong in society, but many jurisdictions do not legally prohibit it.

Norms may also be created and advanced through conscious human design by norm entrepreneurs.[23][24] Norms can arise formally, where groups explicitly outline and implement behavioral expectations. Legal norms typically arise from design.[13][25] A large number of these norms we follow 'naturally' such as driving on the right side of the road in the US and on the left side in the UK, or not speeding in order to avoid a ticket.

Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink identify three stages in the life cycle of a norm:[7]

- Norm emergence: Norm entrepreneurs seek to persuade others to adopt their ideas about what is desirable and appropriate.

- Norm cascade: When a norm has broad acceptance and reaches a tipping point, with norm leaders pressuring others to adopt and adhere to the norm.

- Norm internalization: When the norm has acquired a "taken-for-granted" quality where compliance with the norm is nearly automatic.

They argue that several factors may raise the influence of certain norms:[7]

- Legitimation: Actors that feel insecure about their status and reputation may be more likely to embrace norms.

- Prominence: Norms that are held by actors seen as desirable and successful are more likely to diffuse to others.

- Intrinsic qualities of the norm: Norms that are specific, long-lasting, and universal are more likely to become prominent.

- Path dependency: Norms that are related to preexisting norms are more likely to be widely accepted.

- World time-context: Systemic shocks (such as wars, revolutions and economic crises) may motivate a search for new norms.

Christina Horne and Stefanie Mollborn have identified two broad categories of arguments for the emergence of norms:[14]

- Consequentialism: norms are created when an individual's behavior has consequences and externalities for other members of the group.

- Relationalism: norms are created because people want to attract positive social reactions. In other words, norms do not necessarily contribute to the collective good.

Per consequentialism, norms contribute to the collective good. However, per relationalism, norms do not necessarily contribute to the collective good; norms may even be harmful to the collective.[14]

Some scholars have characterized norms as essentially unstable, thus creating possibilities for norm change.[12][26][27][28] According to Wayne Sandholtz, actors are more likely to persuade others to modify existing norms if they possess power, can reference existing foundational meta-norms, and can reference precedents.[29] Social closeness between actors has been characterized as a key component in sustaining social norms.[30]

Transfer of norms between groups

[edit]Individuals may also import norms from a previous organization to their new group, which can get adopted over time.[31][32] Without a clear indication of how to act, people typically rely on their history to determine the best course forward; what was successful before may serve them well again. In a group, individuals may all import different histories or scripts about appropriate behaviors; common experience over time will lead the group to define as a whole its take on the right action, usually with the integration of several members' schemas.[32] Under the importation paradigm, norm formation occurs subtly and swiftly[32] whereas with formal or informal development of norms may take longer.

Groups internalize norms by accepting them as reasonable and proper standards for behavior within the group. Once firmly established, a norm becomes a part of the group's operational structure and hence more difficult to change. While possible for newcomers to a group to change its norms, it is much more likely that the new individual will adopt the group's norms, values, and perspectives, rather than the other way around.[20]

Deviance from social norms

[edit]

Deviance is defined as "nonconformity to a set of norms that are accepted by a significant number of people in a community or society"[33] More simply put, if group members do not follow a norm, they become tagged as a deviant. In the sociological literature, this can often lead to them being considered outcasts of society. Yet, deviant behavior amongst children is somewhat expected. Except the idea of this deviance manifesting as a criminal action, the social tolerance given in the example of the child is quickly withdrawn against the criminal. Crime is considered one of the most extreme forms of deviancy according to scholar Clifford R. Shaw.[34]

What is considered "normal" is relative to the location of the culture in which the social interaction is taking place. In psychology, an individual who routinely disobeys group norms runs the risk of turning into the "institutionalized deviant." Similar to the sociological definition, institutionalized deviants may be judged by other group members for their failure to adhere to norms. At first, group members may increase pressure on a non-conformist, attempting to engage the individual in conversation or explicate why he or she should follow their behavioral expectations. The role in which one decides on whether or not to behave is largely determined on how their actions will affect others.[35] Especially with new members who perhaps do not know any better, groups may use discretionary stimuli to bring an individual's behavior back into line. Over time, however, if members continue to disobey, the group will give-up on them as a lost cause; while the group may not necessarily revoke their membership, they may give them only superficial consideration.[20] If a worker is late to a meeting, for example, violating the office norm of punctuality, a supervisor or other co-worker may wait for the individual to arrive and pull him aside later to ask what happened. If the behavior continues, eventually the group may begin meetings without him since the individual "is always late." The group generalizes the individual's disobedience and promptly dismisses it, thereby reducing the member's influence and footing in future group disagreements.

Group tolerance for deviation varies across membership; not all group members receive the same treatment for norm violations. Individuals may build up a "reserve" of good behavior through conformity, which they can borrow against later. These idiosyncrasy credits provide a theoretical currency for understanding variations in group behavioral expectations.[36] A teacher, for example, may more easily forgive a straight-A student for misbehaving—who has past "good credit" saved up—than a repeatedly disruptive student. While past performance can help build idiosyncrasy credits, some group members have a higher balance to start with.[36] Individuals can import idiosyncrasy credits from another group; childhood movie stars, for example, who enroll in college, may experience more leeway in adopting school norms than other incoming freshmen. Finally, leaders or individuals in other high-status positions may begin with more credits and appear to be "above the rules" at times.[20][36] Even their idiosyncrasy credits are not bottomless, however; while held to a more lenient standard than the average member, leaders may still face group rejection if their disobedience becomes too extreme.

Deviance also causes multiple emotions one experiences when going against a norm. One of those emotions widely attributed to deviance is guilt. Guilt is connected to the ethics of duty which in turn becomes a primary object of moral obligation. Guilt is followed by an action that is questioned after its doing.[37] It can be described as something negative to the self as well as a negative state of feeling. Used in both instances, it is both an unpleasant feeling as well as a form of self-punishment. Using the metaphor of "dirty hands",[38] it is the staining or tainting of oneself and therefore having to self cleanse away the filth. It is a form of reparation that confronts oneself as well as submitting to the possibility of anger and punishment from others. Guilt is a point in both action and feeling that acts as a stimulus for further "honorable" actions.

A 2023 study found that non-industrial societies varied in their punishments of norm violations. Punishment varied based on the types of norm violations and the socio-economic system of the society. The study "found evidence that reputational punishment was associated with egalitarianism and the absence of food storage; material punishment was associated with the presence of food storage; physical punishment was moderately associated with greater dependence on hunting; and execution punishment was moderately associated with social stratification."[39]

Behavior

[edit]Whereas ideas in general do not necessarily have behavioral implications, Martha Finnemore notes that "norms by definition concern behavior. One could say that they are collectively held ideas about behavior."[4]

Norms running counter to the behaviors of the overarching society or culture may be transmitted and maintained within small subgroups of society. For example, Crandall (1988) noted that certain groups (e.g., cheerleading squads, dance troupes, sports teams, sororities) have a rate of bulimia, a publicly recognized life-threatening disease, that is much higher than society as a whole. Social norms have a way of maintaining order and organizing groups.[40]

In the field of social psychology, the roles of norms are emphasized—which can guide behavior in a certain situation or environment as "mental representations of appropriate behavior".[41] It has been shown that normative messages can promote pro-social behavior, including decreasing alcohol use,[42] increasing voter turnout,[43] and reducing energy use.[44] According to the psychological definition of social norms' behavioral component, norms have two dimensions: how much a behavior is exhibited, and how much the group approves of that behavior.[45]

Social control

[edit]Although not considered to be formal laws within society, norms still work to promote a great deal of social control.[46] They are statements that regulate conduct. The cultural phenomenon that is the norm is the prescriber of acceptable behavior in specific instances. Ranging in variations depending on culture, race, religion, and geographical location, it is the foundation of the terms some know as acceptable as not to injure others, the golden rule, and to keep promises that have been pledged.[47] Without them, there would be a world without consensus, common ground, or restrictions. Even though the law and a state's legislation is not intended to control social norms, society and the law are inherently linked and one dictates the other. This is why it has been said that the language used in some legislation is controlling and dictating for what should or should not be accepted. For example, the criminalization of familial sexual relations is said to protect those that are vulnerable, however even consenting adults cannot have sexual relationships with their relatives. The language surrounding these laws conveys the message that such acts are supposedly immoral and should be condemned, even though there is no actual victim in these consenting relationships.[48]

Social norms can be enforced formally (e.g., through sanctions) or informally (e.g., through body language and non-verbal communication cues).[49] Because individuals often derive physical or psychological resources from group membership, groups are said to control discretionary stimuli; groups can withhold or give out more resources in response to members' adherence to group norms, effectively controlling member behavior through rewards and operant conditioning.[20] Social psychology research has found the more an individual values group-controlled resources or the more an individual sees group membership as central to his definition of self, the more likely he is to conform.[20] Social norms also allow an individual to assess what behaviors the group deems important to its existence or survival, since they represent a codification of belief; groups generally do not punish members or create norms over actions which they care little about.[20][31] Norms in every culture create conformity that allows for people to become socialized to the culture in which they live.[50]

As social beings, individuals learn when and where it is appropriate to say certain things, to use certain words, to discuss certain topics or wear certain clothes, and when it is not. Thus, knowledge about cultural norms is important for impressions,[51] which is an individual's regulation of their nonverbal behavior. One also comes to know through experience what types of people he/she can and cannot discuss certain topics with or wear certain types of dress around. Typically, this knowledge is derived through experience (i.e. social norms are learned through social interaction).[51] Wearing a suit to a job interview in order to give a great first impression represents a common example of a social norm in the white collar work force.

In his work "Order without Law: How Neighbors Settle Disputes", Robert Ellickson studies various interactions between members of neighbourhoods and communities to show how societal norms create order within a small group of people. He argues that, in a small community or neighborhood, many rules and disputes can be settled without a central governing body simply by the interactions within these communities.[52]

Sociology

[edit]In sociology, norms are seen as rules that bind an individual's actions to a specific sanction in one of two forms: a punishment or a reward.[53] Through regulation of behavior, social norms create unique patterns that allow for distinguishing characteristics to be made between social systems.[53] This creates a boundary that allows for a differentiation between those that belong in a specific social setting and those that do not.[53]

For Talcott Parsons of the functionalist school, norms dictate the interactions of people in all social encounters. On the other hand, Karl Marx believed that norms are used to promote the creation of roles in society which allows for people of different levels of social class structure to be able to function properly.[50] Marx claims that this power dynamic creates social order. James Coleman (sociologist) used both micro and macro conditions for his theory.[53] For Coleman, norms start out as goal oriented actions by actors on the micro level.[53] If the benefits do not outweigh the costs of the action for the actors, then a social norm would emerge.[53] The norm's effectiveness is then determined by its ability to enforce its sanctions against those who would not contribute to the "optimal social order."[53]

Heinrich Popitz is convinced that the establishment of social norms, that make the future actions of alter foreseeable for ego, solves the problem of contingency (Niklas Luhmann). In this way, ego can count on those actions as if they would already have been performed and does not have to wait for their actual execution; social interaction is thus accelerated. Important factors in the standardization of behavior are sanctions[54] and social roles.

Operant conditioning

[edit]The probability of these behaviours occurring again is discussed in the theories of B. F. Skinner, who states that operant conditioning plays a role in the process of social norm development. Operant conditioning is the process by which behaviours are changed as a function of their consequences. The probability that a behaviour will occur can be increased or decreased depending on the consequences of said behaviour.

In the case of social deviance, an individual who has gone against a norm will contact the negative contingencies associated with deviance, this may take the form of formal or informal rebuke, social isolation or censure, or more concrete punishments such as fines or imprisonment. If one reduces the deviant behavior after receiving a negative consequence, then they have learned via punishment. If they have engaged in a behavior consistent with a social norm after having an aversive stimulus reduced, then they have learned via negative reinforcement. Reinforcement increases behavior, while punishment decreases behavior.

As an example of this, consider a child who has painted on the walls of her house, if she has never done this before she may immediately seek a reaction from her mother or father. The form of reaction taken by the mother or father will affect whether the behaviour is likely to occur again in the future. If her parent is positive and approving of the behaviour it will likely reoccur (reinforcement) however, if the parent offers an aversive consequence (physical punishment, time-out, anger etc...) then the child is less likely to repeat the behaviour in future (punishment).

Skinner also states that humans are conditioned from a very young age on how to behave and how to act with those around us considering the outside influences of the society and location one is in.[55][56] Built to blend into the ambiance and attitude around us, deviance is a frowned upon action.

Focus theory of normative conduct

[edit]Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren developed the focus theory of normative conduct to describe how individuals implicitly juggle multiple behavioral expectations at once. Expanding on conflicting prior beliefs about whether cultural, situational or personal norms motivate action, the researchers suggested the focus of an individual's attention will dictate what behavioral expectation they follow.[57]

Types

[edit]There is no clear consensus on how the term norm should be used.[58]

Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink distinguish between three types of norms:[7]

- Regulative norms: they "order and constrain behavior"

- Constitutive norms: they "create new actors, interests, or categories of action"

- Evaluative and prescriptive norms: they have an "oughtness" quality to them

Finnemore, Sikkink, Jeffrey W. Legro and others have argued that the robustness (or effectiveness) of norms can be measured by factors such as:

- The specificity of the norm: norms that are clear and specific are more likely to be effective[7][3]

- The longevity of the norm: norms with a history are more likely to be effective[7]

- The universality of the norm: norms that make general claims (rather than localized and particularistic claims) are more likely to be effective[7]

- The prominence of the norm: norms that are widely accepted among powerful actors are more likely to be effective[3]

Christina Horne argues that the robustness of a norm is shaped by the degree of support for the actors who sanction deviant behaviors; she refers to norms regulating how to enforce norms as "metanorms."[59] According to Beth G. Simmons and Hyeran Jo, diversity of support for a norm can be a strong indicator of robustness.[60] They add that institutionalization of a norm raises its robustness.[60] It has also been posited that norms that exist within broader clusters of distinct but mutually reinforcing norms may be more robust.[61]

Jeffrey Checkel argues that there are two common types of explanations for the efficacy of norms:[62]

- Rationalism: actors comply with norms due to coercion, cost-benefit calculations, and material incentives

- Constructivism: actors comply with norms due to social learning and socialization

According to Peyton Young, mechanisms that support normative behavior include:[5]

Descriptive versus injunctive

[edit]Descriptive norms depict what happens, while injunctive norms describe what should happen. Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren (1990) define a descriptive norm as people's perceptions of what is commonly done in specific situations; it signifies what most people do, without assigning judgment. The absence of trash on the ground in a parking lot, for example, transmits the descriptive norm that most people there do not litter.[57][63] An Injunctive norm, on the other hand, transmits group approval about a particular behavior; it dictates how an individual should behave.[57][63][64][65] Watching another person pick up trash off the ground and throw it out, a group member may pick up on the injunctive norm that he ought to not litter.

Prescriptive and proscriptive norms

[edit]Prescriptive norms are unwritten rules that are understood and followed by society and indicate what we should do.[66] Expressing gratitude or writing a Thank You card when someone gives you a gift represents a prescriptive norm in American culture. Proscriptive norms, in contrast, comprise the other end of the same spectrum; they are similarly society's unwritten rules about what one should not do.[66] These norms can vary between cultures; while kissing someone you just met on the cheek is an acceptable greeting in some European countries, this is not acceptable, and thus represents a proscriptive norm in the United States.

Subjective norms

[edit]Subjective norms are determined by beliefs about the extent to which important others want a person to perform a behavior.When combined with attitude toward behavior, subjective norms shape an individual's intentions.[67] Social influences are conceptualized in terms of the pressure that people perceive from important others to perform, or not to perform, a behavior.[65] Social Psychologist Icek Azjen theorized that subjective norms are determined by the strength of a given normative belief and further weighted by the significance of a social referent, as represented in the following equation: SN ∝ Σnimi , where (n) is a normative belief and (m) is the motivation to comply with said belief.[68]

Mathematical representations

[edit]Over the last few decades, several theorists have attempted to explain social norms from a more theoretical point of view. By quantifying behavioral expectations graphically or attempting to plot the logic behind adherence, theorists hoped to be able to predict whether or not individuals would conform. The return potential model and game theory provide a slightly more economic conceptualization of norms, suggesting individuals can calculate the cost or benefit behind possible behavioral outcomes. Under these theoretical frameworks, choosing to obey or violate norms becomes a more deliberate, quantifiable decision.

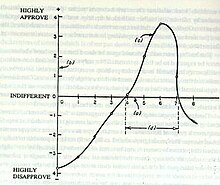

Return potential model

[edit]

Developed in the 1960s, the return potential model provides a method for plotting and visualizing group norms. In the regular coordinate plane, the amount of behavior exhibited is plotted on the X-axis (label a in Figure 1) while the amount of group acceptance or approval gets plotted on the Y-axis (b in Figure 1).[45] The graph represents the potential return or positive outcome to an individual for a given behavioral norm. Theoretically, one could plot a point for each increment of behavior how much the group likes or dislikes that action. For example, it may be the case that among first-year graduate students, strong social norms exist around how many daily cups of coffee a student drinks. If the return curve in Figure 1 correctly displays the example social norm, we can see that if someone drinks 0 cups of coffee a day, the group strongly disapproves. The group disapproves of the behavior of any member who drinks fewer than four cups of coffee a day; the group disapproves of drinking more than seven cups, shown by the approval curve dipping back below zero. As seen in this example, the return potential model displays how much group approval one can expect for each increment of behavior.

- Point of maximum return. The point with the greatest y-coordinate is called the point of maximum return, as it represents the amount of behavior the group likes the best.[45] While c in Figure 1 is labeling the return curve in general, the highlighted point just above it at X=6, represents the point of maximum return. Extending our above example, the point of maximum return for first-year graduate students would be 6 cups of coffee; they receive the most social approval for drinking exactly that many cups. Any more or any fewer cups would decrease the approval.

- Range of tolerable behavior. Label d represents the range of tolerable behavior, or the amount of action the group finds acceptable.[45] It encompasses all the positive area under the curve. In Figure 1, the range of tolerable behavior extends is 3, as the group approves of all behavior from 4 to 7 and 7-4=3. Carrying over our coffee example again, we can see that first-years only approve of having a limited number of cups of coffee (between 4 and 7); more than 7 cups or fewer than 4 would fall outside the range of tolerable behavior. Norms can have a narrower or wider range of tolerable behavior. Typically, a narrower range of behavior indicates a behavior with greater consequences to the group.[20]

- Intensity. The intensity of the norm tells how much the group cares about the norm, or how much group affect is at stake to be won or lost. It is represented in the return potential model by the total amount of area subsumed by the curve, regardless of whether the area is positive or negative.[45] A norm with low intensity would not vary far from the x-axis; the amount of approval or disapproval for given behaviors would be closer to zero. A high-intensity norm, however, would have more extreme approval ratings. In Figure 1, the intensity of the norm appears high, as few behaviors invoke a rating of indifference.

- Crystallization. Finally, norm crystallization refers to how much variance exists within the curve; translated from the theoretical back to the actual norm, it shows how much agreement exists between group members about the approval for a given amount of behavior.[45] It may be that some members believe the norm more central to group functioning than others. A group norm like how many cups of coffee first years should drink would probably have low crystallization since a lot of individuals have varying beliefs about the appropriate amount of caffeine to imbibe; in contrast, the norm of not plagiarizing another student's work would likely have high crystallization, as people uniformly agree on the behavior's unacceptability. Showing the overall group norm, the return potential model in Figure 1 does not indicate the crystallization. However, a return potential model that plotted individual data points alongside the cumulative norm could demonstrate the variance and allow us to deduce crystallization.

Game theory

[edit]Another general formal framework that can be used to represent the essential elements of the social situation surrounding a norm is the repeated game of game theory. Rational choice, a branch of game theory, deals with the relations and actions socially committed among rational agents.[69] A norm gives a person a rule of thumb for how they should behave. However, a rational person acts according to the rule only if it is beneficial for them. The situation can be described as follows. A norm gives an expectation of how other people act in a given situation (macro). A person acts optimally given the expectation (micro). For a norm to be stable, people's actions must reconstitute the expectation without change (micro-macro feedback loop). A set of such correct stable expectations is known as a Nash equilibrium. Thus, a stable norm must constitute a Nash equilibrium.[70] In the Nash equilibrium, no one actor has any positive incentive in individually deviating from a certain action.[71] Social norms will be implemented if the actions of that specific norm come into agreement by the support of the Nash equilibrium in the majority of the game theoretical approaches.[71]

From a game-theoretical point of view, there are two explanations for the vast variety of norms that exist throughout the world. One is the difference in games. Different parts of the world may give different environmental contexts and different people may have different values, which may result in a difference in games. The other is equilibrium selection not explicable by the game itself. Equilibrium selection is closely related to coordination. For a simple example, driving is common throughout the world, but in some countries people drive on the right and in other countries people drive on the left (see coordination game). A framework called comparative institutional analysis is proposed to deal with the game theoretical structural understanding of the variety of social norms.

See also

[edit]- Anomie

- Breaching experiment

- Conformity

- Convention (norm)

- Enculturation

- Etiquette

- Heteronormativity

- Ideal (ethics)

- Ideology

- Morality

- Mores

- Norm (philosophy)

- Norm of reciprocity

- Normality (behavior)

- Normalization (sociology)

- Other (philosophy)

- Philosophical value

- Peer pressure

- Rule complex

- Social norms marketing

- Social structure

- Taboo

References

[edit]- ^ Lapinski, M. K.; Rimal, R. N. (2005). "An explication of social norms". Communication Theory. 15 (2): 127–147. doi:10.1093/ct/15.2.127.

- ^ Pristl, A-C; Kilian, S; Mann, A. (2020). "When does a social norm catch the worm? Disentangling socialnormative influences on sustainable consumption behaviour". Consumer Behav. 20 (3): 635–654. doi:10.1002/cb.1890. S2CID 228807152.

- ^ a b c d e Legro, Jeffrey W. (1997). "Which Norms Matter? Revisiting the "Failure" of Internationalism". International Organization. 51 (1): 31–63. doi:10.1162/002081897550294. ISSN 0020-8183. JSTOR 2703951. S2CID 154368865. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ a b c d e Finnemore, Martha (1996). National Interests in International Society. Cornell University Press. pp. 22–24, 26–27. ISBN 9780801483233. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1rv61rh. Archived from the original on 2021-06-01. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- ^ a b c d e Young, H. Peyton (2015). "The Evolution of Social Norms". Annual Review of Economics. 7 (1): 359–387. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115322. ISSN 1941-1383.

- ^ Tannenwald, Nina (1999). "The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Normative Basis of Nuclear Non-Use". International Organization. 53 (3): 433–468. doi:10.1162/002081899550959. ISSN 0020-8183. JSTOR 2601286.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Finnemore, Martha; Sikkink, Kathryn (1998). "International Norm Dynamics and Political Change". International Organization. 52 (4): 887–917. doi:10.1162/002081898550789. ISSN 0020-8183. JSTOR 2601361. S2CID 10950888. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ Herrmann, Richard K.; Shannon, Vaughn P. (2001). "Defending International Norms: The Role of Obligation, Material Interest, and Perception in Decision Making". International Organization. 55 (3): 621–654. doi:10.1162/00208180152507579. ISSN 0020-8183. JSTOR 3078659. S2CID 145661726. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- ^ a b c d Legros, Sophie; Cislaghi, Beniamino (2020). "Mapping the Social-Norms Literature: An Overview of Reviews". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 15 (1): 62–80. doi:10.1177/1745691619866455. ISSN 1745-6916. PMC 6970459. PMID 31697614.

- ^ a b Gibbs, Jack P. (1965). "Norms: The Problem of Definition and Classification". American Journal of Sociology. 70 (5): 586–594. doi:10.1086/223933. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2774978. PMID 14269217. S2CID 27377450. Archived from the original on 2021-12-23. Retrieved 2021-12-23.

- ^ Katzenstein, Peter (1996). The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics. Columbia University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-231-10469-2. Archived from the original on 2021-09-30. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ^ a b c d e f Sandholtz, Wayne (2017). International Norm Change. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.588. ISBN 9780190228637.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Hecher, Michael; Opp, Karl-Dieter (2001). Social Norms. Russell Sage Foundation. pp. xi. ISBN 978-0-87154-354-7. JSTOR 10.7758/9781610442800. Archived from the original on 2021-05-22. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Horne, Christine; Mollborn, Stefanie (2020). "Norms: An Integrated Framework". Annual Review of Sociology. 46 (1): 467–487. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054658. ISSN 0360-0572. S2CID 225435025. Archived from the original on 2021-05-16. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Young, H. Peyton (2016), "Social Norms", The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2338-1, ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5, S2CID 13026974, retrieved 2021-05-22

- ^ Knight, Jack (1992). Institutions and social conflict. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-511-52817-0. OCLC 1127523562.

- ^ Streeck, Wolfgang; Thelen, Kathleen Ann (2005). Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-928046-9.

- ^ Horne, Christine; Johnson, Monica Kirkpatrick (2021). "Testing an Integrated Theory: Distancing Norms in the Early Months of Covid-19". Sociological Perspectives. 64 (5): 970–987. doi:10.1177/07311214211005493. ISSN 0731-1214.

- ^ Sugden, Robert (1989). "Spontaneous Order". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 3 (4): 85–97. doi:10.1257/jep.3.4.85. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hackman, J.R. (1992). "Group influences on individuals in organizations". In M.D. Dunnette & L.M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, 234-245.

- ^ Chong, D. (2000) Rational lives: norms and values in politics and society

- ^ Gerber, L. & Macionis, J. (2011) Sociology, 7th Canadian ed., p. 65

- ^ Sunstein, Cass R. (1996). "Social Norms and Social Roles" (PDF). Columbia Law Review. 96 (4): 903–968. doi:10.2307/1123430. ISSN 0010-1958. JSTOR 1123430. S2CID 153823271.

- ^ Keck, Margaret E.; Sikkink, Kathryn (1998). Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3444-0. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt5hh13f. Archived from the original on 2021-05-22. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Kendall, D. (2011) Sociology in our times

- ^ Sandholtz, Wayne (2008-03-01). "Dynamics of International Norm Change: Rules against Wartime Plunder". European Journal of International Relations. 14 (1): 101–131. doi:10.1177/1354066107087766. ISSN 1354-0661. S2CID 143721778. Archived from the original on 2021-05-24. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ Wiener, Antje (2008). The Invisible Constitution of Politics: Contested Norms and International Encounters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89596-5. Archived from the original on 2021-05-07. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ Krook, Mona Lena; True, Jacqui (2012-03-01). "Rethinking the life cycles of international norms: The United Nations and the global promotion of gender equality". European Journal of International Relations. 18 (1): 103–127. doi:10.1177/1354066110380963. ISSN 1354-0661. S2CID 145545535.

- ^ Sandholtz, Wayne (2009). International Norms and Cycles of Change. Oxford University Press. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-19-985537-7. Archived from the original on 2021-09-30. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- ^ Bicchieri, Cristina; Dimant, Eugen; Gächter, Simon; Nosenzo, Daniele (2022). "Social proximity and the erosion of norm compliance". Games and Economic Behavior. 132: 59–72. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2021.11.012. hdl:10419/232616. ISSN 0899-8256.

- ^ a b Feldman, D.C. (1984). "The development and enforcement of group norms". Academy of Management Review. 9 (1): 47–55. doi:10.2307/258231. JSTOR 258231.

- ^ a b c Bettenhausen, K.; Murnighan, J.K. (1985). "The emergence of norms in competitive decision-making groups". Administrative Science Quarterly. 30 (3): 350–372. doi:10.2307/2392667. JSTOR 2392667. S2CID 52525302.

- ^ Appelbaum, R. P., Carr, D., Duneir, M., & Giddens, A. (2009). "Conformity, Deviance, and Crime." Introduction to Sociology, New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., p. 173.

- ^ Molinari, Christina (2015). "Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay". In Dobbert, Duane L.; Mackey, Thomas X. (eds.). Deviance: Theories on Behaviors That Defy Social Norms: Theories on Behaviors That Defy Social Norms. ABC-CLIO. pp. 108–118. ISBN 978-1-4408-3324-3. Archived from the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ Drobak, John N. "1. The Role of Social Variables." Norms and the Law. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. N. pag. Print.

- ^ a b c Hollander, E.P. (1958). "Conformity, status, and idiosyncrasy credit". Psychological Review. 65 (2): 117–127. doi:10.1037/h0042501. PMID 13542706.

- ^ Greenspan, Patricia S. "Chapter 4: Moral Residues." Practical Guilt: Moral Dilemmas, Emotions, and Social Norms. N.p.: Oxford UP, 1995. N. pag. Print.

- ^ Greenspan, Patricia S. "Chapter 6: Basing Ethics on Emotion." Practical Guilt: Moral Dilemmas, Emotions, and Social Norms

- ^ Garfield, Zachary H.; Ringen, Erik J.; Buckner, William; Medupe, Dithapelo; Wrangham, Richard W.; Glowacki, Luke (2023). "Norm violations and punishments across human societies". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 5: e11. doi:10.1017/ehs.2023.7. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10426015. PMID 37587937. S2CID 258144948.

- ^ Huang, Peter H.; Wu, Ho-Mou (October 1994). "More Order Without More Law: A Theory of Social Norms and Organizational Cultures". The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 10 (2): 390–406. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jleo.a036856. SSRN 5412.

- ^ Aarts, H.; Dijksterhuis, A. (2003). "The silence of the library: Environment, situational norm, and social behavior" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 84 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.18. PMID 12518968. S2CID 18213113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-09.

- ^ Collins, S. E.; Carey, K. B.; Sliwinski, M. J. (2002). "Mailed personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for at-risk college drinkers". Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 63 (5): 559–567. doi:10.15288/jsa.2002.63.559. PMID 12380852.

- ^ Gerber, A. S.; Rogers, T. (2009). "Descriptive social norms and motivation to vote: everybody's voting and so should you". The Journal of Politics. 71 (1): 178–191. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.37. doi:10.1017/s0022381608090117. S2CID 10783035.

- ^ Brandon, Alec; List, John A.; Metcalfe, Robert D.; Price, Michael K.; Rundhammer, Florian (19 March 2019). "Testing for crowd out in social nudges: Evidence from a natural field experiment in the market for electricity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (12): 5293–5298. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.5293B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1802874115. PMC 6431171. PMID 30104369.

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, J. (1965). "Structural characteristics of norms". In I.D. Steiner & M. Fishbein (Eds.), Current studies in social psychology (pp. 301-309).

- ^ Druzin, Bryan (2016). "Using Social Norms as a Substitute for Law". Albany Law Review. 78: 68. Archived from the original on 2019-07-02. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- ^ Hechter, Michael et al., eds.. "Introduction". Social Norms. Ed. Michael Hechter et al.. Russell Sage Foundation, 2001. xi–xx.

- ^ Roffee, James A (2013). "The Synthetic Necessary Truth Behind New Labour's Criminalisation of Incest". Social & Legal Studies. 23: 113–130. doi:10.1177/0964663913502068. S2CID 145292798.

- ^ Doering, Laura; Ody-Brasier, Amandine (2021). "Time and Punishment: How Individuals Respond to Being Sanctioned in Voluntary Associations". American Journal of Sociology. 127 (2): 441–491. doi:10.1086/717102. ISSN 0002-9602. S2CID 246017181. Archived from the original on 2022-01-18. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

- ^ a b Marshall, G. Oxford Dictionary of Sociology

- ^ a b Kamau, C. (2009) Strategizing impression management in corporations: cultural knowledge as capital. In D. Harorimana (Ed) Cultural implications of knowledge sharing, management and transfer: identifying competitive advantage. Chapter 4. Information Science Reference. ISBN 978-1-60566-790-4

- ^ Ellickson, Robert (1994). Order without Law: How Neighbors Settle Disputes.

- ^ a b c d e f g HYDEN, HAKAN (2022). SOCIOLOGY OF LAW AS THE SCIENCE OF NORMS. [S.l.]: ROUTLEDGE. ISBN 978-1-003-24192-8. OCLC 1274199773.

- ^ See The International Handbook of Sociology, ed. by Stella R. Quah and Arnaud Sales, Sage 2000, p. 62.

- ^ Dobbert, Duane L., and Thomas X. Mackey. "Chapter 9: B.F. Skinner." Deviance: Theories on Behaviors That Defy Social Norms. N.p.: n.p., n.d. N. pag. Print.

- ^ Baker-Sperry, Lori; Grauerholz, Liz (October 2003). "The Pervasiveness and Persistence of the Feminine Beauty Ideal in Children's Fairy Tales". Gender and Society. 17 (5): 711–726. doi:10.1177/0891243203255605. JSTOR 3594706. S2CID 54711044. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. (1990). "A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 58 (6): 1015–1026. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015. S2CID 7867498.

- ^ Hechter, Michael; Opp, Karl-Dieter (2001). Social Norms. Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-1-61044-280-0.[page needed]

- ^ Horne, Christine (2009). "A Social Norms Approach to Legitimacy". American Behavioral Scientist. 53 (3): 400–415. doi:10.1177/0002764209338799. ISSN 0002-7642. S2CID 144726807.

- ^ a b Simmons, Beth A; Jo, Hyeran (2019). "Measuring Norms and Normative Contestation: The Case of International Criminal Law". Journal of Global Security Studies. 4 (1): 18–36. doi:10.1093/jogss/ogy043. ISSN 2057-3170.

- ^ Lantis, Jeffrey S.; Wunderlich, Carmen (2018). "Resiliency dynamics of norm clusters: Norm contestation and international cooperation". Review of International Studies. 44 (3): 570–593. doi:10.1017/S0260210517000626. ISSN 0260-2105. S2CID 148853481. Archived from the original on 2021-05-23. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Checkel, Jeffrey T. (2001). "Why Comply? Social Learning and European Identity Change". International Organization. 55 (3): 553–588. doi:10.1162/00208180152507551. ISSN 0020-8183. JSTOR 3078657. S2CID 143511229. Archived from the original on 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ a b Cialdini, R (2007). "Descriptive social norms as underappreciated sources of social control". Psychometrika. 72 (2): 263–268. doi:10.1007/s11336-006-1560-6. S2CID 121708702.

- ^ Schultz, Nolan; Cialdini, Goldstein; Griskevicius (2007). "The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms" (PDF). Psychological Science. 18 (5): 429–434. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01917.x. hdl:10211.3/199684. PMID 17576283. S2CID 19200458.

- ^ a b Rivis, Amanda, Sheeran, Paschal. "Descriptive Norms as an Additional Predictor in the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis". 2003

- ^ a b Wilson, K.L.; Lizzio, A.J.; Zauner, S.; Gallois, C. (2001). "Social rules for managing attempted interpersonal domination in the workplace: Influence of status and gender". Sex Roles. 44 (3/4): 129–154. doi:10.1023/a:1010998802612. S2CID 142800037.

- ^ Terry, Deborah J.; Hogg, Michael A., eds. (2000). Attitudes, behavior, and social context : the role of norms and group membership. Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-585-17974-3. OCLC 44961884.

- ^ "Author index for volume 50". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 50 (2): 411. 1991. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90029-s. ISSN 0749-5978.

- ^ Voss, Thomas. Game-Theoretical Perspectives on the Emergence of Social Norms. Social Norms, 2001, p.105.

- ^ Bicchieri, Cristina. 2006. The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, New York: Cambridge University Press, Ch. 1

- ^ a b Voss 2001, p. 105

Further reading

[edit]- Axelrod, Robert (1984). The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465021222.

- Appelbaum, R. P., Carr, D., Duneir, M., Giddens, A. (2009). Conformity, Deviance, and Crime. Introduction to Sociology, New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., p. 173.

- Becker, H. S. (1982). "Culture: A Sociological View". Yale Review. 71 (4): 513–527.

- Bicchieri, C. (2006). The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Blumer, H (1956). "Sociological Analysis and the 'Variable". American Sociological Review. 21 (6): 683–690. doi:10.2307/2088418. JSTOR 2088418. S2CID 146998430.

- Boyd, R. & Richerson, P.J. (1985). Culture and the Evolutionary Process, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Burt, R.S. (1987). "Social Contagion and Innovation: Cohesive Versus Structural Equivalence". American Journal of Sociology. 92 (6): 1287–1335. doi:10.1086/228667. S2CID 22380365.

- Rimal, Rajiv N. (2016). "Social Norms: A Review". Review of Communication Research. 4 (1): 1–28. doi:10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2016.04.01.008 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Cialdini, R (2007). "Descriptive Social Norms as Underappreciated Sources of Social Control". Psychometrika. 72 (2): 263–268. doi:10.1007/s11336-006-1560-6. S2CID 121708702.

- Druzin, Bryan H. (24 June 2012). "Eating Peas with One's Fingers: A Semiotic Approach to Law and Social Norms". International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue internationale de Sémiotique juridique. 26 (2): 257–274. doi:10.1007/s11196-012-9271-z. S2CID 85439929.

- Durkheim, E. (1915). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, New York: Free Press.

- Elster, Jon (1 November 1989). "Social Norms and Economic Theory". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 3 (4): 99–117. doi:10.1257/jep.3.4.99. hdl:10535/3264. S2CID 154638062.

- Fehr, Ernst; Fischbacher, Urs; Gächter, Simon (March 2002). "Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms" (PDF). Human Nature. 13 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1007/s12110-002-1012-7. PMID 26192593. S2CID 2901235. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-26.

- Fine, G.A. (2001). Social Norms, ed. by Michael Hechter and Karl-Dieter Opp, New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Greif, A (1994). "Cultural Beliefs and the Organization of Society: A Historical and Theoretical Reflection on Collectivist and Individualist Societies". Journal of Political Economy. 102 (5): 912–950. doi:10.1086/261959. S2CID 153431326.

- Hechter, M. & Karl-Dieter Opp, eds. (2001). Social Norms, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Heiss, J. (1981). "Social Roles", In Social Psychology: Sociological Perspectives, Rosenburg, M. & Turner, R.H. (eds.), New York: Basic Books.

- Hochschild, A. (1989). "The Economy of Gratitude", In D.D. Franks & E.D. McCarthy (Eds.), The Sociology of Emotions: Original Essays and Research Papers, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Horne, C. (2001). "Social Norms". In M. Hechter & K. Opp (Eds.), New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kahneman, D.; Miller, D.T. (1986). "Norm Theory: Comparing reality to its alternatives" (PDF). Psychological Review. 80 (2): 136–153. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.93.2.136. S2CID 7706059. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-11.

- Kollock, P (1994). "The emergence of exchange structures: An experimental study of uncertainty, commitment, and trust". American Journal of Sociology. 100 (2): 313–45. doi:10.1086/230539. S2CID 144646491.

- Kohn, M.L. (1977). Class and Conformity: A Study in Values, 2nd ed., Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Macy, M.W.; Skvoretz, J. (1998). "The evolution of trust and cooperation between strangers: A computational model". American Sociological Review. 63 (5): 638–660. JSTOR 2657332.

- Mark, N (1998). "Birds of a feather sing together". Social Forces. 77 (2): 453–485. doi:10.1093/sf/77.2.453. S2CID 143739215.

- McElreath, Richard; Boyd, Robert; Richerson, Peter J. (February 2003). "Shared Norms and the Evolution of Ethnic Markers" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 44 (1): 122–130. doi:10.1086/345689. S2CID 8796947. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-07.

- Opp, K (1982). "The evolutionary emergence of norms". British Journal of Social Psychology. 21 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1982.tb00522.x.

- Posner, Eric A. (1996). "The Regulation of Groups: The Influence of Legal and Nonlegal Sanctions on Collective Action". The University of Chicago Law Review. 63 (1): 133–197. doi:10.2307/1600068. JSTOR 1600068. Archived from the original on 2020-12-04. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- Posner, E. (2000). Law and Social Norms. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press

- Prentice, D. A.; Miller, D. T. (1993). "Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 64 (2): 243–256. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.470.522. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.243. PMID 8433272. S2CID 24004422.

- Schultz, P. Wesley; Nolan, Jessica M.; Cialdini, Robert B.; Goldstein, Noah J.; Griskevicius, Vladas (25 November 2016). "The Constructive, Destructive, and Reconstructive Power of Social Norms". Psychological Science. 18 (5): 429–434. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01917.x. hdl:10211.3/199684. PMID 17576283. S2CID 19200458.

- Scott, J.F. (1971). Internalization of Norms: A Sociological Theory of Moral Commitment, Englewoods Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice–Hall.

- Ullmann-Margalit, E. (1977). The Emergence of Norms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Yamagishi, T.; Cook, K.S.; Watabe, M. (1998). "Uncertainty, trust, and commitment formation in the United States and Japan". American Journal of Sociology. 104 (1): 165–194. doi:10.1086/210005. S2CID 144931651.

- Young, H.P. (2008). "Social norms". The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition.

External links

[edit]- Bicchieri, Cristina; Muldoon, Ryan. "Social Norms". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.