Soča dialect

| Soča dialect | |

|---|---|

| Isonzo dialect | |

| Native to | Slovenia |

| Region | Upper Soča Valley |

| Ethnicity | Slovenes |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

The Soča dialect | |

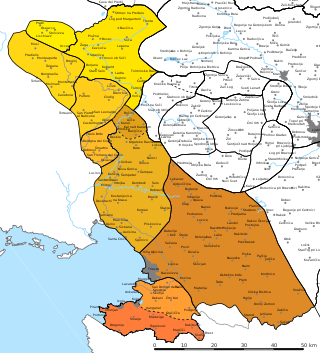

The Soča dialect (Slovene: obsoško narečje[1] [ɔpˈsóːʃkɔ naˈɾéːt͡ʃjɛ]) is a Slovene dialect spoken in upper Soča Valley. It is one of the most archaic Slovene dialects, together with the Natisone Valley, Torre Valley, and Rosen Valley dialects. It borders the Karst dialect to the south, Natisone Valley dialect to the southwest, Torre Valley and Resian dialects to the west, Fiulian and Carinthian Bavarian to the northwest, Gail Valley dialect to the north, Upper Carniolan dialect to the east, and Tolmin dialect to the southeast. The dialect belongs to the Littoral dialect group, and it evolved from Soča–Idrija dialect base.[2][3]

Geographical extension

[edit]The Soča dialect is the only dialect in the Littoral dialect group that is not spoken in Italy. It spans the area from Volčanski Ruti in the south to Borjana and Žaga in the west, north up to the Vršič Pass, with the northernmost settlements being Strmec na Predelu and Trenta. There is no geographical border on its eastern side, it is spoken west of Tolmin, and it is still spoken in villages such as Tolminske Ravne. It is thus spoken in the entire territory of the Municipality of Bovec, in most of the Municipality of Kobarid (except for the area around Breginj and Livek on the border with Italy, where the Torre Valley and Natisone Valley dialects are spoken), and in several villages in the western and southern parts of the Municipality of Tolmin. Larger settlements include Volče, Volarje, Idrsko, Drežnica, Kobarid, Borjana, Srpenica, Žaga, Bovec, Čezsoča, Soča, and Log pod Mangartom.[2]

Accentual changes

[edit]The Soča dialect has pitch accent on long syllables, which are differentiated from short syllables. The southern microdialects have retained the Alpine Slovene accentuation, whereas the northern microdialects have undergone the *ženȁ → *žèna and *məglȁ → *mə̀gla accent shifts[4] under influence from the Gail Valley dialect.

Phonology

[edit]All long and later lengthened e-like vowels (*ě, *ę, *e) turned into iẹ, and o-like vowels (*ǫ, *o) turned into uo, except that final *ō turned into uː or into eː after *w. Secondarily stressed *e and *o in the northern microdialects turned into eː and oː, respectively, but oː changed into eː after *w. The vowels *ū, *ā, and *ī remained unchanged, and *ə̄ turned into aː. Syllabic *ł̥̄ turned into uː.[5]

Vowel reduction affected all vowels. Ukanye (*o, *ǫ → u) is common, as well as simplification of *e, *ě, *ę, *i, *u, and *a after the stress into e̥.[6]

Palatal consonants are only palatalized or completely hardened (depalatalized) (*ĺ → l’; *ń → n’/ń; ŕ → r; t’ → č/č́). *ĺ and *ń turned into the clusters lj and nj, respectively, before a vowel and *t’ turned into jč after stressed e. Before a front vowel, *w turned into ƀ (betacizem),[7] and elsewhere it remained. The consonant *g turned into ɣ and into voiced h at the end of a word or partially spirantized into ǥ. The consonants b and d also spirantized in some microdialects into ƀ and đ, respectively. Final consonants are not always devoiced; only b → p and d → θ/t. The consonant *t in the cluster tl and at the end of a word also turns into k. The consonant ǯ́ is present in loanwords, and in some dialects *f turned into x.[8][9][10]

Morphology

[edit]The Soča dialect retains neuter gender in all numbers and the dual still exists, but it is used inconsistently. The feminine dual l-participle form merged with the plural. The dialect uses the long infinitive. Verbs in -i- always have the accent on the root (ˈɣóːri vs. standard Slovene gorȋ 'to burn'), and with some reflexive verbs the accent in the imperative shifted to the end (uble̥ˈcìː se vs. standard Slovene oblẹ́ci se 'get dressed').[11]

Vocabulary

[edit]A dictionary of words used in the northern microdialects, particularly in Bovec, was written by Barbara Ivančič Kutin in 2007.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Smole, Vera. 1998. "Slovenska narečja." Enciklopedija Slovenije vol. 12, pp. 1–5. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, p. 2.

- ^ a b "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Šekli (2018:329–331)

- ^ Šekli (2018:310–314)

- ^ Ivančič Kutin (2007:12–14)

- ^ Ivančič Kutin (2007:14–15)

- ^ Greenberg, Marc L. 2002. Zgodovinsko glasoslovje slovenskega jezika. Transl. Marta Pirnat-Greenberg. Maribor: Aristej, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Ivančič Kutin (2007:16)

- ^ Toporišič, Jože. 1992. Enciklopedija slovenskega jezika. Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, p. 155.

- ^ Logar, Tine (1996). Kenda-Jež, Karmen (ed.). Dialektološke in jezikovnozgodovinske razprave [Dialectological and etymological discussions] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša. p. 32. ISBN 961-6182-18-8.

- ^ Ivančič Kutin (2007:17–18)

- ^ Ivančič Kutin (2007)

Bibliography

[edit]- Ivančič Kutin, Barbara (2007). Likar, Vojislav (ed.). Slovar bovškega govora (in Slovenian) (1st ed.). Ljubljana: Založba ZRC. doi:10.3986/9789610503194. ISBN 978-961-6568-92-0. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Šekli, Matej (2018). Legan Ravnikar, Andreja (ed.). Tipologija lingvogenez slovanskih jezikov. Collection Linguistica et philologica (in Slovenian). Translated by Plotnikova, Anastasija. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. ISBN 978-961-05-0137-4.