Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders

| Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders | |

|---|---|

Defendants Robert Thompson and Benjamin J. Davis with supporters | |

| When | 1949–1958 |

| Defendants | 144 leaders of the Communist Party USA |

| Allegation | Violating the Smith Act, by conspiring to violently overthrow the government |

| Where | Federal courthouses in New York, Los Angeles, Honolulu, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Seattle, Baltimore, Seattle, Detroit, St. Louis, Denver, Boston, Puerto Rico, New Haven |

| Outcome | Over 100 convictions, with sentences up to six years in prison and each a $10,000 fine |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

|

The Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders in New York City from 1949 to 1958 were the result of US federal government prosecutions in the postwar period and during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. Leaders of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) were accused of violating the Smith Act, a statute that prohibited advocating violent overthrow of the government. The defendants argued that they advocated a peaceful transition to socialism, and that the First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of speech and of association protected their membership in a political party. Appeals from these trials reached the US Supreme Court, which ruled on issues in Dennis v. United States (1951) and Yates v. United States (1957).

The first trial of eleven communist leaders was held in New York in 1949; it was one of the lengthiest trials in United States history. Numerous supporters of the defendants protested outside the courthouse on a daily basis. The trial was featured twice on the cover of Time magazine. The defense frequently antagonized the judge and prosecution; five defendants were jailed for contempt of court because they disrupted the proceedings. The prosecution's case relied on undercover informants, who described the goals of the CPUSA, interpreted communist texts, and testified of their own knowledge that the CPUSA advocated the violent overthrow of the US government.

While the first trial was under way, events outside the courtroom influenced public perception of communism: the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon, and communists prevailed in the Chinese Civil War. In this period, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had also begun conducting investigations and hearings of writers and producers in Hollywood suspected of communist influence. Public opinion was overwhelmingly against the defendants in New York. After a 10-month trial, the jury found all 11 defendants guilty. The judge sentenced them to terms of up to five years in federal prison, and sentenced all five defense attorneys to imprisonment for contempt of court. Two of the attorneys were subsequently disbarred.

After the first trial, the prosecutors – encouraged by their success – prosecuted more than 100 additional CPUSA officers for violating the Smith Act. Some were tried solely because they were members of the Party. Many of these defendants had difficulty finding attorneys to represent them. The trials decimated the leadership of the CPUSA. In 1957, eight years after the first trial, the US Supreme Court's Yates decision brought an end to similar prosecutions. It ruled that defendants could be prosecuted only for their actions, not for their beliefs.

Background

[edit]

After the revolution in Russia in 1917, the communist movement gradually gained footholds in many countries around the world. In Europe and the US, communist parties were formed, generally allied with trade union and labor causes. During the First Red Scare of 1919–1920, many U.S. capitalists were fearful that Bolshevism and anarchism would lead to disruption within the US.[1] In the late 1930s, state and federal legislatures passed laws designed to expose communists, including laws requiring loyalty oaths, and laws requiring communists to register with the government. Even the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a free-speech advocacy organization, passed a resolution in 1939 expelling communists from its leadership ranks.[2]

Following Congressional investigation of left-wing and right-wing extremist political groups in the mid-1930s, support grew for a statutory prohibition of their activities. The alliance of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the August 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and their invasion of Poland in September gave the movement added impetus. In 1940 the Congress passed the Alien Registration Act of 1940 (known as the Smith Act) which required all non-citizen adult residents to register with the government, and made it a crime "to knowingly or willfully advocate ... the duty, necessity, desirability, ... of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence ... with the intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States...."[3][4] Five million non-citizens were fingerprinted and registered following passage of the Act.[5] The first persons convicted under the Smith Act were members of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in Minneapolis in 1941.[6] Leaders of the CPUSA, bitter rivals of the Trotskyist SWP, supported the Smith Act prosecution of the SWP – a decision they would later regret.[7] In 1943, the government used the Smith Act to prosecute American Nazis; that case ended in a mistrial when the judge died of a heart attack.[8] Anxious to avoid alienating the Soviet Union, then an ally, the government did not prosecute any communists under the law during World War II.[9]

The CPUSA's membership peaked at around 80,000 members during World War II under the leadership of Earl Browder, who was not a strict Stalinist and cooperated with the US government during the war.[9][10] In late 1945, hardliner William Z. Foster took over leadership of the CPUSA, and steered it on a course adhering to Stalin's policies.[9] The CPUSA was not very influential in American politics, and by 1948 its membership had declined to 60,000 members.[11] Truman did not feel that the CPUSA was a threat (he dismissed it as a "non problem") yet he made the specter of communism a campaign issue during the 1948 election.[12]

The perception of communism in the US was shaped by the Cold War, which began after World War II when the Soviet Union failed to uphold the commitments it made at the Yalta Conference. Instead of holding elections for new governments, as agreed at Yalta, the Soviet Union occupied several Eastern European countries, leading to a strained relationship with the US. Subsequent international events served to increase the apparent danger that communism posed to Americans: the Stalinist threats in the Greek Civil War (1946–1949); the Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948; and the 1948 blockade of Berlin.[11]

The view of communism was also affected by evidence of espionage in the US conducted by agents of the USSR. In 1945, a Soviet spy, Elizabeth Bentley, repudiated the USSR and provided a list of Soviet spies in the US to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).[13] The FBI also had access to secret Soviet communications, available from the Venona decryption effort, which revealed significant efforts by Soviet agents to conduct espionage within the US.[11][14] The growing influence of communism around the world and the evidence of Soviet spies within the US motivated the Department of Justice – spearheaded by the FBI – to initiate an investigation of communists within the US.[9]

1949 trial

[edit]

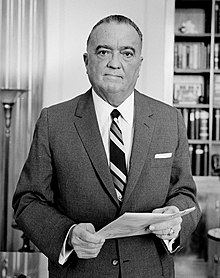

In July 1945, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover instructed his agents to begin gathering information on CPUSA members, leading to a 1,850-page report published in 1946 which outlined a case for their prosecution.[15] As the Cold War continued to intensify in 1947, Congress held a hearing at which the Hollywood Ten refused to testify about alleged involvement with the CPUSA, leading to their convictions for contempt of Congress in early 1948.[16] The same year, Hoover recommended to the Department of Justice that they bring charges against the CPUSA leaders, with the intention of rendering the Party ineffective.[17] John McGohey, a federal prosecutor from the Southern District of New York, was given the lead role in prosecuting the case and charged twelve leaders of the CPUSA with violations of the Smith Act. The specific charges against the defendants were first, that they conspired to overthrow the US government by violent means, and second, that they belonged to an organization that advocated the violent overthrow of the government.[4][18] The indictment, issued on June 29, 1948, asserted that the CPUSA had been in violation of the Smith Act since July 1945.[19] The twelve defendants, arrested in late July 1948, were all members of the National Board of the CPUSA:[19][20]

- Benjamin J. Davis Jr. – Chairman of the CPUSA's Legislative Committee and Council-member of New York City

- Eugene Dennis – CPUSA General Secretary

- William Z. Foster – CPUSA National Secretary (indicted; but not tried due to illness)

- John Gates – Leader of the Young Communist League

- Gil Green – Member of the National Board (represented by A.J. Isserman)

- Gus Hall – Member of the CPUSA National Board

- Irving Potash – Furriers Union official

- Jack Stachel – Editor of the Daily Worker

- Robert G. Thompson – Leader of the New York branch of CPUSA

- John Williamson – Member of the CPUSA Central Committee (represented by A.J. Isserman)

- Henry Winston – Member of the CPUSA National Board

- Carl Winter – Lead of the Michigan branch of CPUSA

Hoover hoped that all 55 members of the CPUSA's National Committee would be indicted and was disappointed that the prosecutors chose to pursue only twelve.[21] A week before the arrests, Hoover complained to the Justice Department – recalling the arrests and convictions of over one hundred leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1917 – "the IWW was crushed and never revived, similar action at this time would have been as effective against the Communist Party."[22]

Start of the trial

[edit]

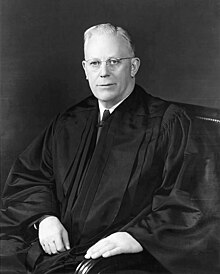

The 1949 trial was held in New York City at the Foley Square federal courthouse of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. Judge Harold Medina, a former Columbia University professor who had been on the bench for 18 months when the hearing began, presided.[23] Before becoming a judge, Medina successfully argued the case of Cramer v. United States before the Supreme Court, defending a German-American charged with treason.[24][25]

The trial opened on November 1, 1948, and preliminary proceedings and jury selection lasted until January 17, 1949; the defendants first appeared in court on March 7, and the case concluded on October 14, 1949.[26][27] Although later trials surpassed it, in 1949 it was the longest federal trial in US history.[26][28] The trial was one of the country's most contentious legal proceedings and sometimes had a "circus-like atmosphere".[29] Four hundred police officers were assigned to the site on the opening day of the trial.[26]

Public opinion

[edit]The opinion of the American public and the news media was overwhelming in favor of conviction.[30]

Magazines, newspapers, and radio reported on the case heavily; Time magazine featured the trial on its cover twice with stories titled "Communists: The Presence of Evil" and "Communists: The Little Commissar" (referring to Eugene Dennis).[31]

Most American newspapers supported the prosecution, such as the New York World-Telegram which reported that the Communist Party would soon be punished.[32] The New York Times, in an editorial, felt that the trial was warranted and denied assertions of the Party that the trial was a provocation comparable to the Reichstag fire.[33] The Christian Science Monitor took a more detached view in an editorial: "The outcome of the case will be watched by government and political parties around the world as to how the United States, as an outstanding exponent of democratic government, intends to share the benefits of its civil liberties and yet protect them if and when they appear to be abused by enemies from within".[32]

Support for the prosecutions was not universal, however. During the proceedings, there were days when several thousand picketers protested in Foley Square outside the courthouse, chanting slogans like "Adolf Hitler never died / He's sitting at Medina's side".[27] In response, the US House of Representatives passed a bill in August to outlaw picketing near federal courthouses, but the Senate did not vote on it before the end of the trial.[26][34]

Journalist William L. Shirer was skeptical of the trial, writing "no overt act of trying to forcibly overthrow our government is charged ... The government's case is simply that by being members and leaders of the Communist Party, its doctrines and tactics being what they are, the accused are guilty of conspiracy".[32] The Washington Post wrote that the purpose of the government's legal attack on the CPUSA was "not so much the protection and security of the state as the exploitation of justice for the purpose of propaganda."[35]

Third-party presidential candidate Henry A. Wallace claimed that the trial was an effort by the Truman administration to create an atmosphere of fear, writing "we Americans have far more to fear from those actions which are intended to suppress political freedom than from the teaching of ideas with which we are in disagreement."[36] Farrell Dobbs of the SWP wrote – despite the fact that the CPUSA had supported Dobbs' prosecution under the Smith Act in 1941 – "I want to state in no uncertain terms that I as well as the Socialist Workers Party support their struggle against the obnoxious Smith Act, as well as against the indictments under that act".[37]

Before the trial began, supporters of the defendants decided on a campaign of letter-writing and demonstrations: the CPUSA urged its members to bombard Truman with letters requesting that the charges be dropped.[38] Later, supporters similarly flooded Judge Medina with telegrams and letters urging him to dismiss the charges.[39]

The defense was not optimistic about the probability of success. After the trial was over, defendant Gates wrote: "The anti-communist hysteria was so intense, and most Americans were so frightened by the Communist issue, that we were convicted before our trial even started".[40]

Prosecution

[edit]Prosecutor John McGohey did not assert that the defendants had a specific plan to violently overthrow the US government, but rather alleged that the CPUSA's philosophy generally advocated the violent overthrow of governments.[41] The prosecution called witnesses who were either undercover informants, such as Angela Calomiris and Herbert Philbrick, or former communists who had become disenchanted with the CPUSA, such as Louis Budenz.[42] The prosecution witnesses testified about the goals and policies of the CPUSA, and they interpreted the statements of pamphlets and books (including The Communist Manifesto) and works by such authors as Karl Marx and Joseph Stalin.[43] The prosecution argued that the texts advocated violent revolution, and that by adopting the texts as their political foundation, the defendants were guilty of advocating violent overthrow of the government.[9]

Calomiris was recruited by the FBI in 1942 and infiltrated the CPUSA, gaining access to a membership roster.[44] She received a salary from the FBI during her seven years as an informant.[44] Calomiris identified four of the defendants as members of the CPUSA and provided information about its organization.[45] She testified that the CPUSA espoused violent revolution against the government, and that the CPUSA – acting on instructions from Moscow – had attempted to recruit members working in key war industries.[46]

Budenz, a former communist, was another important witness for the prosecution who testified that the CPUSA subscribed to a philosophy of violent overthrow of the government.[41] He also testified that the clauses of the constitution of the CPUSA that disavowed violence were decoys written in "Aesopian language" which were put in place specifically to protect the CPUSA from prosecution.[41]

Defense

[edit]

The five attorneys who volunteered to defend the communists were familiar with leftist causes and supported the defendants' rights to espouse socialist viewpoints. They were Abraham Isserman, George W. Crockett Jr., Richard Gladstein, Harry Sacher, and Louis F. McCabe.[26][47] Defendant Eugene Dennis represented himself. The ACLU was dominated by anti-communist leaders during the 1940s, and did not enthusiastically support persons indicted under the Smith Act; but it did submit an amicus brief endorsing a motion for dismissal of the charges.[48]

The defense employed a three-pronged strategy: First, they sought to portray the CPUSA as a conventional political party, which promoted socialism by peaceful means; second, they attacked the trial as a capitalist venture which could never provide a fair outcome for proletarian defendants; and third, they used the trial as an opportunity to publicize CPUSA policies.[49]

The defense made pre-trial motions arguing that the defendants' right to trial by a jury of their peers had been denied because, at that time, a potential grand juror had to meet a minimum property requirement, effectively eliminating the less affluent from service.[50] The defense also argued that the jury selection process for the trial was similarly flawed.[51] Their objections to the jury selection process were not successful and jurors included four African Americans and consisted primarily of working-class citizens.[41]

A primary theme of the defense was that the CPUSA sought to convert the US to socialism by education, not by force.[52] The defense claimed that most of the prosecution's documentary evidence came from older texts that pre-dated the 1935 Seventh World Congress of the Comintern, after which the CPUSA rejected violence as a means of change.[53] The defense attempted to introduce documents into evidence which represented the CPUSA's advocacy of peace, claiming that these policies superseded the older texts that the prosecution had introduced which emphasized violence.[52] Medina excluded most of the material proposed by the defense because it did not directly pertain to the specific documents the prosecution had produced. As a result, the defense complained that they were unable to portray the totality of their belief system to the jury.[54]

The defense attorneys developed a "labor defense" strategy, by which they attacked the entire trial process, including the prosecutor, the judge, and the jury selection process.[18] The strategy involved verbally disparaging the judge and the prosecutors, and may have been an attempt to provoke a mistrial.[55] Another aspect of the labor defense was an effort to rally popular support to free the defendants, in the hope that public pressure would help achieve acquittals.[39] Throughout the course of the trial, thousands of supporters of the defendants flooded the judge with protests, and marched outside the courthouse in Foley Square. The defense used the trial as an opportunity to educate the public about their beliefs, so they focused their defense around the political aspects of communism, rather than rebutting the legal aspects of the prosecution's evidence.[56] Defendant Dennis chose to represent himself so he could, in his role as attorney, directly address the jury and explain communist principles.[56]

Courtroom atmosphere

[edit]The trial was one of the country's most contentious legal proceedings and sometimes had a "circus-like atmosphere".[29] Four hundred police officers were assigned to the site on the opening day of the trial.[26]

The defense deliberately antagonized the judge by making a large number of objections and motions,[23] which led to numerous bitter engagements between the attorneys and Judge Medina.[57] Despite the aggressive defense tactics and a voluminous letter-writing campaign directed at Medina, he stated "I will not be intimidated".[58] Out of the chaos, an atmosphere of "mutual hostility" arose between the judge and attorneys.[55] Judge Medina attempted to maintain order by removing disorderly defendants. In the course of the trial, Medina sent five of the defendants to jail for outbursts, including Hall because he shouted "I've heard more law in a kangaroo court", and Winston – an African American – for shouting "more than five thousand Negroes have been lynched in this country".[59] Several times in July and August, the judge held defense attorneys in contempt of court, and told them their punishment would be meted out upon conclusion of the trial.[60]

Fellow judge James L. Oakes described Medina as a fair and reasonable judge, and wrote that "after the judge saw what the lawyers were doing, he gave them a little bit of their own medicine, too."[25] Legal scholar and historian Michal Belknap writes that Medina was "unfriendly" to the defense, and that "there is reason to believe that Medina was biased against the defendants", citing a statement Medina made before the trial: "If we let them do that sort of thing [postpone the trial start], they'll destroy the government".[61] According to Belknap, Medina's behavior towards the defense may have been exacerbated by the fact that another federal judge had died of a heart attack during the 1943 trial involving the Smith Act.[39][62] Some historians speculate that Medina came to believe that the defense was deliberately trying to provoke him into committing a legal error with the goal of achieving a mistrial.[25][54]

Events outside the courtroom

[edit]

During the ten-month trial, several events occurred in America that intensified the nation's anti-communist sentiment: The Judith Coplon Soviet espionage case was in progress; former government employee Alger Hiss was tried for perjury stemming from accusations that he was a communist (a trial also held at the Foley Square courthouse); labor leader Harry Bridges was accused of perjury when he denied being a communist; and the ACLU passed an anti-communist resolution.[64][65] Two events during the final month of the trial may have been particularly influential: On September 23, 1949, Truman announced that the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear bomb; and on October 1, 1949, the Chinese Communist Party prevailed in the Chinese Civil War.[64]

Defendants Irving Potash and Benjamin J. Davis were among the audience members attacked as they left a September 4 concert headlined by Paul Robeson in Peekskill, New York. It was given to benefit the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), which was funding the defendants' legal expenses.[63] Hundreds lined the roads leaving the performance grounds and threw rocks and bottles at the departing vehicles without interference by the police.[66] Over 140 people suffered injuries, including Potash, whose eyes were struck by glass from a broken windshield.[67] The trial was suspended for two days while Potash recovered from his injuries.[68]

Convictions and sentencing

[edit]

On October 14, 1949, after the defense rested their case, the judge gave the jury instructions to guide them in reaching a verdict. He instructed the jury that the prosecution was not required to prove that the danger of violence was "clear and present"; instead, the jury should consider if the defendants had advocated communist policy as a "rule or principle of action" with the intention of inciting overthrow by violence "as speedily as circumstances would permit".[70] This instruction was in response to the defendants, who endorsed the "clear and present danger" test, yet that test was not adopted as law by the Supreme Court.[71] The judge's instructions included the phrase "I find as a matter of law that there is sufficient danger of a substantive evil..." which would later be challenged by the defense during their appeals.[70] After deliberating for seven and one-half hours, the jury returned guilty verdicts against all eleven defendants.[72] The judge sentenced ten defendants to five years and a $10,000 fine each ($128,056 in 2023 dollars[73]). The eleventh defendant, Robert G. Thompson – a veteran of World War II – was sentenced to three years in consideration of his wartime service.[74] Thompson said that he took "no pleasure that this Wall Street judicial flunky has seen fit to equate my possession of the Distinguished Service Cross to two years in prison."[75]

Immediately after the jury rendered a verdict, Medina turned to the defense attorneys saying he had some "unfinished business" and he held them in contempt of court, and sentenced all of them to jail terms ranging from 30 days to six months; Dennis, acting as his own attorney, was also cited.[26][76] Since the contempt sentences were based on behavior witnessed by the judge, no hearings were required for the contempt charges, and the attorneys were immediately handcuffed and led to jail.[77][78]

Public reaction

[edit]The vast majority of the public, and most news media, endorsed the verdict.[72] Typical was a letter to the New York Times: "The Communist Party may prove to be a hydra-headed monster unless we can discover how to kill the body as well as how to cut off its heads."[79] The day of the convictions, New York Gov. Thomas E. Dewey and Senator John Foster Dulles praised the verdicts.[80]

Some vocal supporters of the defendants spoke out in their defense. A New York resident wrote: "I am not afraid of communism ... I am only afraid of the trend in our country today away from the principles of democracy."[81] Another wrote: "the trial was a political trial ... Does not the Soviet Union inspire fear in the world at large precisely because masses of human beings have no confidence in the justice of its criminal procedures against dissidents? ... I trust that the Supreme Court will be able to correct a grave error in the operation of our political machinery by finding the ... Smith bill unconstitutional."[82] William Z. Foster wrote: "every democratic movement in the United States is menaced by this reactionary verdict ... The Communist Party will not be dismayed by this scandalous verdict, which belies our whole national democratic traditions. It will carry the fight to the higher courts, to the broad masses of the people."[80] Vito Marcantonio of the American Labor Party wrote that the verdict was "a sharp and instant challenge to the freedom of every American."[80] The ACLU issued a statement reiterating its opposition to the Smith Act, because it felt the act criminalized political advocacy.[80]

Abroad, the trial received little mention in mainstream press, but Communist newspapers were unanimous in their condemnation.[83] The Moscow press wrote that Medina showed "extraordinary prejudice"; the London communist newspaper wrote that the defendants had been convicted only of "being communists"; and in France, a paper decried the convictions as "a step on the road that leads to war."[83]

On October 21, President Truman appointed prosecutor John McGohey to serve as a US District Court judge.[84] Judge Medina was hailed as a national hero and received 50,000 letters congratulating him on the trial outcome.[85] On October 24, Time magazine featured Medina on its cover,[86] and soon thereafter he was asked to consider running for governor of New York.[87] On June 11, 1951, Truman nominated Medina to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, where he served until 1980.[88]

Bail and prison

[edit]After sentencing, the defendants posted bail, enabling them to remain free during the appeal process. The $260,000 bail ($3,329,455 in 2023 dollars[73]) was provided by Civil Rights Congress, a non-profit trust fund which was created to assist CPUSA members with legal expenses.[89] While out on bail, Hall was appointed to a position in the secretariat within the CPUSA. Eugene Dennis was – in addition to his Smith Act charges – fighting contempt of Congress charges stemming from an incident in 1947 when he refused to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He appealed the contempt charge, but the Supreme Court upheld his conviction for contempt in March 1950, and he began to serve a one-year term at that time.[90]

While waiting for their legal appeals to be heard, the CPUSA leaders became convinced that the government would undertake the prosecution of many additional Party officers. To ensure continuity of their leadership, they decided that four of the defendants should go into hiding and lead the CPUSA from outside prison.[91] The defendants were ordered to report to prison on July 2, 1951, after the Supreme Court upheld their convictions and their legal appeals were exhausted.[91] When July arrived, only seven defendants reported to prison, and four (Winston, Green, Thompson, and Hall) went into hiding, forfeiting $80,000 bail ($1,024,448 in 2023 dollars[73]).[91] Hall was captured in Mexico in 1951, trying to flee to the Soviet Union. Thompson was captured in California in 1952. Both had three years added to their five-year sentences.[91] Winston and Green surrendered voluntarily in 1956 after they felt that anti-communist hysteria had diminished.[91] Some of the defendants did not fare well in prison: Thompson was attacked by an anti-communist inmate; Winston became blind because a brain tumor was not treated promptly; Gates was put into solitary confinement because he refused to lock the cells of fellow inmates; and Davis was ordered to mop floors because he protested against racial segregation in prison.[91][92]

Perception of communism after the trial

[edit]

After the convictions, the Cold War continued in the international arena. In December 1950, Truman declared a national emergency in response to the Korean War.[93] The First Indochina War continued in Vietnam, in which communist forces in the north fought against French Union forces in the south.[93] The US expanded the Radio Free Europe broadcasting system in an effort to promote Western political ideals in Eastern Europe.[93] In March 1951, American communists Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted of spying for the Soviet Union.[93] In 1952, the US exploded its first hydrogen bomb, and the Soviet Union followed suit in 1953.[93]

Domestically, the Cold War was in the forefront of national consciousness. In February 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy rose suddenly to national fame when he claimed "I have here in my hand a list" of over 200 communists who were employed in the State Department.[94] In September 1950, the US Congress passed the McCarran Internal Security Act, which required communist organizations to register with the government, and formed the Subversive Activities Control Board to investigate persons suspected of engaging in subversive activities. High-profile hearings involving alleged communists included the 1950 conviction of Alger Hiss, the 1951 trial of the Rosenbergs, and the 1954 investigation of J. Robert Oppenheimer.[40]

The convictions in the 1949 trial encouraged the Department of Justice to prepare for additional prosecutions of CPUSA leaders. Three months after the trial, in January 1950, a representative of the Justice Department testified before Congress during appropriation hearings to justify an increase in funding to support Smith Act prosecutions.[95] He testified that there were 21,105 potential persons that could be indicted under the Smith Act, and that 12,000 of those would be indicted if the Smith Act was upheld as constitutional.[95] The FBI had compiled a list of 200,000 persons in its Communist Index; since the CPUSA had only around 32,000 members in 1950, the FBI explained the disparity by asserting that for every official Party member, there were ten persons who were loyal to the CPUSA and ready to carry out its orders.[96] Seven months after the convictions, in May 1950, Hoover gave a radio address in which he declared "communists have been and are today at work within the very gates of America.... Wherever they may be, they have in common one diabolic ambition: to weaken and to eventually destroy American democracy by stealth and cunning."[97]

Other federal government agencies also worked to undermine organizations, such as the CPUSA, they considered subversive: The Internal Revenue Service investigated 81 organizations that were deemed to be subversive, threatening to revoke their tax exempt status; Congress passed a law prohibiting members of subversive organizations from obtaining federal housing benefits; and attempts were made to deny Social Security benefits, veterans benefits, and unemployment benefits to communist sympathizers.[98]

Legal appeals of 1949 trial

[edit]The 1949 trial defendants appealed to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in 1950.[99] In the appeal they raised issues about the use of informant witnesses, the impartiality of the jury and judge, the judge's conduct, and free speech.[99] Their free speech arguments raised important constitutional issues: they asserted that their political advocacy was protected by the First Amendment, because the CPUSA did not advocate imminent violence, but instead merely promoted revolution as an abstract concept.

Free speech law

[edit]One of the major issues raised on appeal was that the defendants' political advocacy was protected by the First Amendment, because the CPUSA did not advocate imminent violence, but instead merely promoted revolution as an abstract concept.[55]

In the early twentieth century, the primary legal test used in the United States to determine if speech could be criminalized was the bad tendency test.[100] Rooted in English common law, the test permitted speech to be outlawed if it had a tendency to harm public welfare.[100] One of the earliest cases in which the Supreme Court addressed punishment after material was published was Patterson v. Colorado (1907) in which the Court used the bad tendency test to uphold contempt charges against a newspaper publisher who accused Colorado judges of acting on behalf of local utility companies.[100][101]

Anti-war protests during World War I gave rise to several important free speech cases related to sedition and inciting violence. In the 1919 case Schenck v. United States the Supreme Court held that an anti-war activist did not have a First Amendment right to speak out against the draft.[102][103] In his majority opinion, Justice Holmes introduced the clear and present danger test, which would become an important concept in First Amendment law; but the Schenck decision did not formally adopt the test.[102] Holmes later wrote that he intended the clear and present danger test to refine, not replace, the bad tendency test.[71][104] Although sometimes mentioned in subsequent rulings, the clear and present danger test was never endorsed by the Supreme Court as a test to be used by lower courts when evaluating the constitutionality of legislation that regulated speech.[105][106]

The Court continued to use the bad tendency test during the early twentieth century in cases such as 1919's Abrams v. United States which upheld the conviction of anti-war activists who passed out leaflets encouraging workers to impede the war effort.[107] In Abrams, Holmes and Justice Brandeis dissented and encouraged the use of the clear and present test, which provided more protection for speech.[108] In 1925's Gitlow v. New York, the Court extended the First Amendment to the states, and upheld the conviction of Gitlow for publishing the "Left Wing Manifesto".[109] Gitlow was decided based on the bad tendency test, but the majority decision acknowledged the validity of the clear and present danger test, yet concluded that its use was limited to Schenck-like situations where the speech was not specifically outlawed by the legislature.[71][110] Brandeis and Holmes again promoted the clear and present danger test, this time in a concurring opinion in 1927's Whitney v. California decision.[71][111] The majority did not adopt or use the clear and present danger test, but the concurring opinion encouraged the Court to support greater protections for speech, and it suggested that "imminent danger" – a more restrictive wording than "present danger" – should be required before speech can be outlawed.[112] After Whitney, bad tendency tests continued to be used by the Court in cases such 1931's Stromberg v. California, which held that a 1919 California statute banning red flags was unconstitutional.[113]

The clear and present danger test was invoked by the majority in the 1940 Thornhill v. Alabama decision in which a state anti-picketing law was invalidated.[105][114] Although the Court referred to the clear and present danger test in a few decisions following Thornhill,[115] the bad tendency test was not explicitly overruled,[105] and the clear and present danger test was not applied in several subsequent free speech cases involving incitement to violence.[116]

Appeal to the federal Court of Appeals

[edit]In May 1950, one month before the appeals court heard oral arguments in the CPUSA case, the Supreme Court ruled on free speech issues in American Communications Association v. Douds. In that case the Court considered the clear and present danger test, but rejected it as too mechanical and instead introduced a balancing test.[117] The federal appeals court heard oral arguments in the CPUSA case on June 21–23, 1950. Two days later, on June 25, South Korea was invaded by forces from communist North Korea, marking the start of the Korean War; during the two months that the appeals court judges were forging their opinions, the Korean War dominated the headlines.[118] On August 1, 1950, the appeals court unanimously upheld the convictions in an opinion written by Judge Learned Hand. Judge Hand considered the clear and present danger test, but his opinion adopted a balancing approach similar to that suggested in American Communications Association v. Douds.[71][99][119] In his opinion, Hand wrote:

In each case they [the courts] must ask whether the gravity of the 'evil', discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger.... The American Communist Party, of which the defendants are the controlling spirits, is a highly articulated, well contrived, far spread organization, numbering thousands of adherents, rigidly and ruthlessly disciplined, many of whom are infused with a passionate Utopian faith that is to redeem mankind.... The violent capture of all existing governments is one article of the creed of that faith [communism], which abjures the possibility of success by lawful means.[120]

The opinion specifically mentioned the contemporary dangers of communism worldwide, with emphasis on the Berlin Airlift.[88]

Appeal to the Supreme Court

[edit]

The defendants appealed the Second Circuit's decision to the Supreme Court in Dennis v. United States. During the Supreme Court appeal, the defendants were assisted by the National Lawyers Guild and the ACLU.[118] The Supreme Court limited its consideration to the questions of the constitutionality of the Smith Act and the jury instructions, and did not rule on the issues of impartiality, jury composition, or informant witnesses.[99] The 6–2 decision was issued on June 4, 1951, and upheld Hand's decision. Chief Justice Fred Vinson's opinion stated that the First Amendment does not require that the government must wait "until the putsch is about to be executed, the plans have been laid and the signal is awaited" before it interrupts seditious plots.[121] In his opinion, Vinson endorsed the balancing approach used by Judge Hand:[122][123]

Chief Judge Learned Hand ... interpreted the [clear and present danger] phrase as follows: 'In each case, [courts] must ask whether the gravity of the "evil", discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger.' We adopt this statement of the rule. As articulated by Chief Judge Hand, it is as succinct and inclusive as any other we might devise at this time. It takes into consideration those factors which we deem relevant, and relates their significances. More we cannot expect from words.

Vinson's opinion also addressed the contention that Medina's jury instructions were faulty. The defendants claimed that Medina's statement that "as matter of law that there is sufficient danger of a substantive evil that the Congress has a right to prevent to justify the application of the statute under the First Amendment of the Constitution" was erroneous, but Vinson concluded that the instructions were an appropriate interpretation of the Smith Act.[122]

The Supreme Court was, in one historian's words, "bitterly divided" on the First Amendment issues presented by Dennis.[124] Justices Hugo Black and William O. Douglas dissented from the majority opinion. In his dissent, Black wrote "public opinion being what it now is, few will protest the conviction of these Communist petitioners. There is hope, however, that, in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society."[122][125] Following the Dennis decision, the Court utilized balancing tests for free speech cases, and rarely invoked the clear and present danger test.[126]

Appeal of contempt sentences

[edit]One who reads this record will have difficulty in determining whether members of the bar conspired to drive a judge from the bench or whether the judge used the authority of the bench to whipsaw the lawyers, to taunt and tempt them, and to create for himself the role of the persecuted. I have reluctantly concluded that neither is blameless, that there is fault on each side, that we have here the spectacle of the bench and the bar using the courtroom for an unseemly demonstration of garrulous discussion and of ill will and hot tempers.

— Justice William O. Douglas, in his dissenting opinion in Sacher v. United States[127]

The defense attorneys appealed their contempt sentences, which were handed out by Judge Medina under Rule 42 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.[128] The attorneys raised a variety of issues on appeal, including the purported misconduct of the judge, and the claim that they were deprived of due process because there was no hearing to evaluate the merits of the contempt charge. They argued that the contempt charges would prevent future CPUSA defendants from obtaining counsel, because attorneys would be afraid of judicial retaliation.[129][130] The initial appeal to the federal appeals court was not successful: The court reviewed Medina's actions, and reversed some specifications of contempt, but affirmed the convictions.[129][131]

The attorneys then appealed to the Supreme Court which denied the initial petition, but later reconsidered and accepted the appeal.[132] The Supreme Court limited their review to the question, "was the charge of contempt, as and when certified, one which the accusing judge was authorized under Rule 42(a) to determine and punish himself; or was it one to be adjudged and punished under Rule 42(b) only by a judge other than the accusing one and after notice, hearing, and opportunity to defend?".[129] The Supreme Court, in an opinion written by Justice Robert Jackson, upheld the contempt sentences by a 5–3 vote.[91] Jackson's opinion stated that "summary punishment always, and rightly, is regarded with disfavor, and, if imposed in passion or pettiness, brings discredit to a court as certainly as the conduct it penalizes. But the very practical reasons which have led every system of law to vest a contempt power in one who presides over judicial proceedings also are the reasons which account for it being made summary."[133]

Trials of "second-tier" officials

[edit]

After the 1949 convictions, prosecutors waited until the constitutional issues were settled by the Supreme Court before they tried additional leaders of the CPUSA.[3] When the 1951 Dennis decision upholding the convictions was announced, prosecutors initiated indictments of 132 additional CPUSA leaders, called "second string" or "second-tier" defendants.[134][135] The second-tier defendants were prosecuted in three waves: 1951, 1954, and 1956.[3] Their trials were held in more than a dozen cities, including Los Angeles (15 CPUSA defendants, including Dorothy Healey, leader of the California branch of the CPUSA); New York (21 defendants, including National Committee members Claudia Jones and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn); Honolulu, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Baltimore, Seattle, Detroit, St. Louis, Denver, Boston, Puerto Rico, and New Haven.[136][137]

The second-tier defendants had a difficult time finding lawyers to represent them. The five defense attorneys at the 1949 trial had been jailed for contempt of court,[77] and both Abraham J. Isserman and Harry Sacher were disbarred.[138] Attorneys for other Smith Act defendants routinely found themselves attacked by courts, attorneys' groups, and licensing boards, leading many defense attorneys to shun Smith Act cases.[139] Some defendants were forced to contact more than one hundred attorneys before finding one who would take their case;[140] defendant Steve Nelson could not find a lawyer in Pennsylvania who would represent him in his Smith Act trial, so he was forced to represent himself.[141] Judges sometimes had to appoint unwilling counsel for defendants who could not find a lawyer to take their cases.[142] The National Lawyers Guild provided some lawyers to the defendants, but in 1953 Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. threatened to list the Guild as a subversive organization, causing half its members to leave.[143]

Some second-tier defendants were unable to post bail because the government refused to permit the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) legal defense fund to provide bail funding.[144][145] The CRC had run afoul of the judicial system because it had posted bail for the 1949 trial defendants, and four of those defendants skipped bail in 1951.[144] Leaders of the CRC were called before a grand jury and asked to identify the donors who had contributed money to the bail fund.[144] Novelist Dashiell Hammett, a manager of the CRC fund, invoked the Fifth Amendment, refused to identify donors, and was sentenced to six months in prison.[144]

To supply witnesses for the second-tier trials, the Justice Department relied on a dozen informants, who traveled full-time from trial to trial, testifying about communism and the CPUSA. The informants were paid for their time; for example, Budenz earned $70,000 ($803,158 in 2023 dollars[73]) from his activities as a witness.[146]

California convictions reversed

[edit]

The federal appeals courts upheld all convictions of second-tier officials. The Supreme Court refused to hear their appeals until 1956, when it agreed to hear the appeal of the California defendants; this led to the landmark Yates v. United States decision.[135][147] Fourteen second-tier CPUSA officials from California who had been convicted of Smith Act violations appealed, and on June 17, 1957, known as "Red Monday", the Supreme Court reversed their convictions. By the time the Court ruled 6–1 in Yates v. United States, four of the Supreme Court Justices who had supported the 1951 Dennis decision had been replaced, including Chief Justice Vinson. He was replaced by Chief Justice Earl Warren.[124]

The decision in Yates undermined the 1951 Dennis decision by holding that contemplation of abstract, future violence may not be prohibited by law, but that urging others to act in violent ways may be outlawed.[148] Writing for the majority, Justice John Marshall Harlan introduced the notion of balancing society's right of self-preservation against the right to free speech.[124] He wrote:[149][150]

We are thus faced with the question whether the Smith Act prohibits advocacy and teaching of forcible overthrow as an abstract principle, divorced from any effort to instigate action to that end, so long as such advocacy or teaching is engaged in with evil intent. We hold that it does not.... In failing to distinguish between advocacy of forcible overthrow as an abstract doctrine and advocacy of action to that end, the District Court appears to have been led astray by the holding in Dennis that advocacy of violent action to be taken at some future time was enough.

Yates did not rule the Smith Act unconstitutional or overrule the Dennis decision, but Yates limited the application of the Act to such a degree that it became nearly unenforceable.[151][152] The Yates decision outraged some conservative members of Congress, who introduced legislation to limit judicial review of certain sentences related to sedition and treason. This bill did not pass.[153]

Membership clause

[edit]Four years after the Yates decision, the Supreme Court reversed the conviction of another second-tier CPUSA leader, John Francis Noto of New York, in the 1961 Noto v. United States case.[154] Noto was convicted under the membership clause of the Smith Act, and he challenged the constitutionality of that clause on appeal.[155] The membership clause was in the portion of the Smith Act that made it a crime "to organize or help to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States by force or violence; or to be or become a member of, or affiliate with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof ...".[4] In a unanimous decision, the court reversed the conviction because the evidence presented at trial was not sufficient to demonstrate that the Party was advocating action (as opposed to mere doctrine) of forcible overthrow of the government.[155] On behalf of the majority, Justice Harlan wrote:[156]

The evidence was insufficient to prove that the Communist Party presently advocated forcible overthrow of the Government not as an abstract doctrine, but by the use of language reasonably and ordinarily calculated to incite persons to action, immediately or in the future.... In order to support a conviction under the membership clause of the Smith Act, there must be some substantial direct or circumstantial evidence of a call to violence now or in the future which is both sufficiently strong and sufficiently pervasive to lend color to the otherwise ambiguous theoretical material regarding Communist Party teaching and to justify the inference that such a call to violence may fairly be imputed to the Party as a whole, and not merely to some narrow segment of it.

The decision did not rule the membership clause unconstitutional.[155] In their concurring opinions, Justices Black and Douglas argued that the membership clause of the Smith Act was unconstitutional on its face as a violation of the First Amendment, with Douglas writing that "the utterances, attitudes, and associations in this case ... are, in my view, wholly protected by the First Amendment, and not subject to inquiry, examination, or prosecution by the Federal Government."[154][155]

Final conviction

[edit]In 1958 at his second trial, Junius Scales, the leader of the North Carolina branch of the CPUSA, became the final CPUSA member convicted under the Smith Act. He was the only one convicted after the Yates decision.[3][157] Prosecutors pursued Scales' case because he specifically advocated violent political action and gave demonstrations of martial arts skills.[3] Scales was accused of violating the membership clause of the Smith Act, not the clause prohibiting advocacy of violence against the government.[158] In his appeal to the Supreme Court, Scales contended that the 1950 McCarran Internal Security Act rendered the Smith Act's membership clause ineffective, because the McCarran Act explicitly stated that membership in a communist party does not constitute a per se violation of any criminal statute.[159][160] In 1961, the Supreme Court, in a 5–4 decision, upheld Scales' conviction, finding that the Smith Act membership clause was not obviated by the McCarran Act, because the Smith Act required prosecutors to prove first, that there was direct advocacy of violence; and second, that the defendant's membership was substantial and active, not merely passive or technical.[161][162] Two Justices of the Supreme Court who had supported the Yates decision in 1957, Harlan and Frankfurter, voted to uphold Scales' conviction.[153]

Scales was the only defendant convicted under the membership clause. All others were convicted of conspiring to overthrow the government.[158] President Kennedy commuted his sentence on Christmas Eve, 1962, making Scales the final Smith Act defendant released from prison.[163] Scales is the only Supreme Court decision to uphold a conviction based solely upon membership in a political party.[164]

Aftermath

[edit]Legal

[edit]The Yates and Noto decisions undermined the Smith Act and marked the beginning of the end of CPUSA membership inquiries.[165] When the trials came to an end in 1958, 144 people had been indicted, resulting in 105 convictions, with cumulative sentences totaling 418 years and $435,500 ($4,996,789 in 2023 dollars[73]) in fines.[166] Fewer than half the convicted communists served jail time.[3] The Smith Act, 18 U.S.C. § 2385, though amended several times, has not been repealed.[167]

For two decades after the Dennis decision, free speech issues related to advocacy of violence were decided using balancing tests such as the one initially articulated in Dennis.[168] In 1969, the court established stronger protections for speech in the landmark case Brandenburg v. Ohio which held that "the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action".[169][170] Brandenburg is now the standard applied by the Court to free speech issues related to advocacy of violence.[171]

CPUSA downfall

[edit]The Smith Act trials decimated the leadership ranks of the CPUSA.[18] Immediately after the 1949 trial, the CPUSA – alarmed at the undercover informants that had testified for the prosecution – initiated efforts to identify and exclude informers from its membership. The FBI encouraged these suspicions by planting fabricated evidence which suggested that many innocent Party members were FBI informants.[172] Dennis attempted to provide leadership from inside the Atlanta penitentiary, but prison officials censored his mail and successfully isolated him from the outside world.[135] Prison officials from the Lewisburg prison prevented Williamson from writing to anyone other than immediate family members.[135] Lacking leadership, the CPUSA suffered from internal dissension and disorder, and by 1953 the CPUSA's leadership structure was inoperative.[135][173] In 1956, Nikita Khrushchev revealed the reality of Stalin's purges, causing many remaining CPUSA members to quit in disillusionment.[174] By the late 1950s, the CPUSA's membership had dwindled to 5,000, of whom over 1,000 may have been FBI informants.[175]

CPUSA leaders

[edit]

The defendants at the 1949 trial were released from prison in the mid-1950s. Gus Hall served as a Party leader for another 40 years; he supported the policies of the Soviet Union, and ran for president four times from 1972 to 1984.[92] Eugene Dennis continued to be involved in the CPUSA and died in 1961. Benjamin J. Davis died in 1964. Jack Stachel, who continued working on the Daily Worker, died in 1966.[92] John Gates became disillusioned with the CPUSA after the revelation of Stalin's Great Purge; he quit the Party in 1958 and later gave a television interview to Mike Wallace in which he blamed the CPUSA's "unshaken faith" in the Soviet Union for the organization's downfall.[176]

Henry Winston became co-chair of the CPUSA (with Hall) in 1966 and was awarded the Order of the October Revolution by the Soviet Union in 1976.[92] After leaving prison, Carl Winter resumed Party activities, became editor of the Daily Worker in 1966, and died in 1991.[92][177] Gil Green was released from Leavenworth prison in 1961 and continued working with the CPUSA to oppose the Vietnam War.[92] Party leader William Z. Foster, 69 years old at the time of the 1949 trial, was never tried due to ill health; he retired from the Party in 1957 and died in Moscow in 1961.[178]

John Williamson was released early, in 1955, and deported to England, although he had lived in the United States since the age of ten.[179] Irving Potash moved to Poland after his release from prison, then re-entered the United States illegally in 1957, and was arrested and sentenced to two years for violating immigration laws.[179] Robert G. Thompson skipped bail, was captured in 1953, and sentenced to an additional four years.[180] He died in 1965 and US Army officials refused him burial in Arlington National Cemetery. His wife challenged that decision, first losing in US District Court and then winning in the Court of Appeals.[181] Defense attorney George W. Crockett Jr. later became a Democratic congressman from Michigan.[182]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Murray, Robert K. (1955), Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919–1920, University of Minnesota Press, pp 82–104, 150–169, ISBN 978-0-313-22673-1.

- ^ Walker, pp 128–133.

- ^ a b c d e f Levin, p 1488, available online, accessed June 13, 2012

- ^ a b c The Smith Act was officially called the Alien Registration Act of 1940. Text of 1940 version. The Act has been amended since then: Text of 2012 version. The portion of the 1940 Act that was relevant to the CPUSA trials was: "Sec. 2. (a) It shall be unlawful for any person— (1) to knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence, or by the assassination of any officer of any such government; (2) with the intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States, to print, publish, edit, issue, circulate, sell, distribute, or publicly display any written or printed matter advocating, advising, or teaching the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence. (3) to organize or help to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States by force or violence; or to be or become a member of, or affiliate with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof...."

- ^ Kennedy, David M., The Library of Congress World War II Companion, Simon and Schuster, 2007, p 86, ISBN 978-0-7432-5219-5.

- ^ Belknap (1994), p 179. President Roosevelt insisted on the prosecution because the SWP had challenged a Roosevelt ally.

- ^ Smith, Michael Steven, "Smith Act Trials, 1949", in Encyclopedia of the American Left, Oxford University Press, 1998, p 756.

- ^ Belknap (1994), pp 196, 207.

See also: Ribuffo, Leo, "United States v. McWilliams: The Roosevelt Administration and the Far Right", in Belknap (1994), pp 179–206. - ^ a b c d e Belknap (1994), p 209.

- ^ Hoover, J. Edgar, Masters of Deceit: the Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It, Pocket Books, 1958, p 5 (80,000 peak in 1944).

- ^ a b c Belknap (1994), p 210.

- ^ Belknap (1994), p 210. Truman quoted by Belknap. Belknap writes that Truman considered the CPUSA to be "a contemptible minority in a land of freedom".

- ^ Theoharis, Atahn, The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, p 27, ISBN 978-0-89774-991-6.

- ^ Haynes, pp 8–22.

- ^ Redish, pp 81–82, 248. Redish cites Schrecker and Belknap.

Belknap (1994), p 210.

Powers, p 214. - ^ Tyler, G. L., "House Un-American Activities Committee", in Finkelman, p 780.

- ^ Belknap (1994), p 210.

Redish, pp 81–82. - ^ a b c Redish, pp 81–82.

- ^ a b Belknap (1994), p 211.

- ^ Belknap (1977), p 51.

Belknap (1994), p 207.

Lannon, p 122.

Morgan, p 314.

Powers, p 215. - ^ Powers, p 215.

- ^ Morgan, p 314. Hoover quoted by Morgan.

Powers, p 215. - ^ a b Morgan, p 314.

Sabin, p 41. - ^ Cramer v. United States, 325 U.S. 1, 1945.

- ^ a b c Oakes, p 1460.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Communist Trial Ends with 11 Guilty", Life, October 24, 1949, p 31.

- ^ a b Morgan, p 315.

- ^ Longer trials have been held since then, for example a 20-month trial in 1988 (Longest Mob Trial Ends, Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1988. Retrieved June 10, 2012).

- ^ a b Walker, p 185.

Morgan, p 315.

Sabin, pp 44–45. "Circus-like" are Sabin's words. - ^ Belknap (1994), p 217. Belknap quotes an editorial from the left-leaning The New Republic, written after the prosecution rested on May 19, 1949: "[the prosecution] failed to make out the overwhelming case that many people anticipated before the trial began".

- ^ "Communists: The Little Commissar", Time, April 25, 1949 (Cover photo: Eugene Dennis).

"Communists: The Presence of Evil", Time: October 24, 1949. (Cover photo: Harold Medina).

"Communists: the Field Day is Over", Time, (article, not cover), August 22, 1949.

"Communists: Evolution or Revolution?", Time, April 4, 1949.

See also Life magazine articles "Communist trial ends with 11 guilty", Life, October 24, 1949, p 31; and "Unrepentant reds emerge", Life, March 14, 1955, p 30. - ^ a b c Martelle, p 76. Martelle states that Shirer's statement was published in the New York Star.

- ^ "The Communist Indictments" (PDF). The New York Times. July 22, 1948. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Walker, p 186.

- ^ Belknap (1994), p 214. Washington Post quoted by Belknap.

- ^ "Indicted Reds Get Wallace Support" (PDF). New York Times. July 22, 1948. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Farrell Dobbs (July 24, 1948). "Letters to the Times: Indictment of Communists". New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2012.; letter dated July 22, 1948

- ^ Belknap (1994), p 212.

- ^ a b c Redish, p 82.

- ^ a b Belknap (1994), p 208.

- ^ a b c d Belknap (1994), p 214.

- ^ Belknap (1994), pp 216–217.

- ^ Belknap (1994), p 214.

Belknap (1994), p 209. - ^ a b Mahoney, M.H., Women in Espionage: A Biographical Dictionary, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 1993, pp 37–39.

- ^ "Girl Official of Party Stuns Reds at Trial", Chicago Daily Tribune, April 27, 1949, p 21.

- ^ Martelle, pp.148–149.

- ^ Sabin, p 42.

Attorney Maurice Sugar participated in an advisory role. - ^ Walker, pp 185–187. Many local affiliates of the ACLU supported second-tier communist defendants in the 1950s.

- ^ Walker, p 185.

Belknap (1994), p 217.

Sabin, pp 44–46. - ^ Belknap (1994), p 213.

Walker, p 185.

Starobin, p 206.

Medina's ruling on the jury selection issue is 83 F.Supp. 197 (1949). The issue was addressed by the appeals court in 183 F.2d 201 (2d Cir. 1950). - ^ Belknap (1994), p 213.

- ^ a b Belknap (1994), p 219.

- ^ Belknap (1994), pp 219–220.

Starobin, p 207. - ^ a b Belknap (1994), p 220.

- ^ a b c Sabin, p 46. "Mutual hostility" is Sabin's characterization.

- ^ a b Belknap (1994), p 218.

- ^ Redish, p 82.

Sabin, p 46. - ^ Belknap (1994), p 218. Medina quoted by Belknap.

- ^ Sabin, pp 46–47. Sabin writes that only four defendants were cited.

Morgan, p 315 (Morgan erroneously quotes Winston as saying 500 – the correct quote is 5,000).

Martelle, p 175. - ^ Martelle, p 190.

- ^ Belknap (1994), pp 212, 220.

- ^ Belknap (2001), p 860.

- ^ a b Martelle, p 193.

- ^ a b Sabin, p 45.

- ^ Johnson, John W., "Icons of the Cold War: The Hiss–Chambers Case", in Historic U.S. Court Cases: An Encyclopedia (Vol 1), (John W. Johnson, Ed.), Taylor & Francis, 2001, p 79, ISBN 978-0-415-93019-2 (Hiss in same building).

- ^ Martelle, pp 197–204.

- ^ Belknap (1977), p 105.

- ^ Martelle, pp 204–205.

- ^ Martelle, p 217.

- ^ a b Sabin, p 45.

Belknap (1994), p 221.

Redish, p 87.

One instruction from Medina to the jury was "I find as a matter of law that there is sufficient danger of a substantive evil that the Congress had a right to prevent, to justify the application of the statute under the First Amendment of the Constitution." - ^ a b c d e Dunlap, William V., "National Security and Freedom of Speech", in Finkelman (vol 1), pp 1072–1074.

- ^ a b Belknap (1994), p 221.

- ^ a b c d e 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Morgan, p 317.

- ^ Belknap (1994), p 221.

Morgan, p 317. Thompson quoted by Morgan. - ^ Attorney Maurice Sugar, who participated in an advisory role, was not cited for contempt.

- ^ a b Sabin, p 47.

- ^ The regulation governing the contempt sentences was Rule 42(a) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.

Some of the contempt sentences were postponed pending appeal; for instance, Crockett served four months in an Ashland, Kentucky, Federal prison in 1952. See Smith, Jessie Carney, Notable Black American Men, Volume 1, Gale, 1998, p 236, ISBN 978-0-7876-0763-0. - ^ George D. Wilkinson (October 19, 1949). "Letters to the Times: Communism Threat Not Ended" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2012.; letter dated October 16, 1949

- ^ a b c d "Vigorous and Varied Reactions Mark Result of Communist Trial". New York Times. October 15, 1949. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Mrs. D. Brouwer (October 19, 1949). "Letters to the Times: Trend Away from Democracy" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2012.; letter written October 14, 1949

- ^ David D. Driscoll (October 19, 1949). "Letters to the Times: Political Statutes Queried" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2012.; letter written October 16, 1949

- ^ a b "Verdict Assailed Abroad". New York Times. October 16, 1949. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "McGohey, John F. X.", Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ Belknap (1994) p 221 (50,000 letters).

Oakes, p 1460 ("national hero"). - ^ Time, October 24, 1949. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ Oakes, p 1460. Medina chose to not run for governor.

- ^ a b Smith, J. Y., "Harold R. Medina, 102, Dies; Ran 1949 Conspiracy Trial", The Washington Post, March 17, 1990.

Sabin, p 79 (Cold War in Dennis case). - ^ Belknap (1977), p 123.

- ^ Associated Press, "Justices Uphold Red Conviction", Spokesman-Review, March 28, 1950.

The conviction was upheld in Dennis v. United States, 339 U.S. 162 (1950). - ^ a b c d e f g Belknap (1994), pp 224–225.

- ^ a b c d e f Martelle, pp 256–257.

- ^ a b c d e Gregory, Ross, Cold War America, 1946 to 1990, Infobase Publishing, 2003, pp 48–53, ISBN 978-1-4381-0798-1.

Kort, Michael, The Columbia Guide to the Cold War, Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-231-10773-0.

Walker, Martin, The Cold War: a History, Macmillan, 1995, ISBN 978-0-8050-3454-7. - ^ "Communists in Government Service, McCarthy Says". United States Senate History Website. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

McCarthy made the claim in The Wheeling speech. - ^ a b Sabin, p 56.

See also Fast, Howard, "The Big Finger", Masses & Mainstream, March, 1950, pp 62–68. - ^ Sabin, p 56 (200,000 figure).

Navasky, p 26 (32,000 figure). - ^ Heale, M. J., American Anticommunism: Combating the Enemy Within, 1830–1970, JHU Press, 1990, p 162, ISBN 978-0-8018-4051-7. Hoover quoted by Heale.

Sabin, p 56. - ^ Sabin, p 60.

- ^ a b c d Belknap (2005), pp 258–259.

- ^ a b c Rabban, pp 132–134, 190–199.

- ^ Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U.S. 454 (1907).

- ^ a b Killian, p 1093.

- ^ Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919).

- ^ Rabban, pp 285–286.

- ^ a b c Killian, pp 1096, 1100.

Currie, David P., The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The Second Century, 1888–1986, Volume 2, University of Chicago Press, 1994, p 269, ISBN 978-0-226-13112-2.

Konvitz, Milton Ridvad, Fundamental Liberties of a Free People: Religion, Speech, Press, Assembly, Transaction Publishers, 2003, p 304, ISBN 978-0-7658-0954-4.

Eastland, p 47. - ^ The Court would adopt the imminent lawless action test in 1969's Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), which some commentators view as a modified version of the clear and present danger test.

- ^ Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919).

The bad tendency test was also used in Frohwerk v. United States, 249 U.S. 204 (1919); Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211 (1919); and Schaefer v. United States, 251 U.S. 466 (1920).

See Rabban, David, "Clear and Present Danger Test", in The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, p 183, 2005, ISBN 978-0-19-517661-2 . - ^ Killian, p. 1094.

Rabban, p 346.

Redish, p 102. - ^ Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925).

- ^ Redish, p 102.

Kemper, p 653. - ^ Whitney v. California 274 U.S. 357 (1927).

- ^ Redish pp 102–104.

Killian, p 1095. - ^ Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931).

Killian, p 1096.

Another case from that era that used the bad tendency test was Fiske v. Kansas, 274 U.S. 380 (1927). - ^ Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940).

- ^ Including Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940): "When clear and present danger of riot, disorder, interference with traffic upon the public streets, or other immediate threat to public safety, peace, or order appears, the power of the State to prevent or punish is obvious.… we think that, in the absence of a statute narrowly drawn to define and punish specific conduct as constituting a clear and present danger to a substantial interest of the State, the petitioner's communication, considered in the light of the constitutional guarantees, raised no such clear and present menace to public peace and order as to render him liable to conviction of the common law offense in question."

And Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941): "And, very recently [in Thornhill] we have also suggested that 'clear and present danger' is an appropriate guide in determining the constitutionality of restrictions upon expression … What finally emerges from the 'clear and present danger' cases is a working principle that the substantive evil must be extremely serious, and the degree of imminence extremely high, before utterances can be punished." - ^ Antieu, Chester James, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, Wm. S. Hein Publishing, 1998, p 219, ISBN 978-1-57588-443-1. Antieu names Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951); Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire 315 U.S. 568 (1942); and Kovacs v. Cooper, 335 U.S. 77 (1949).

- ^ Eastland, p 47.

Killian, p 1101.

American Communications Association v. Douds 339 U.S. 382 (1950). - ^ a b Belknap (1994), p 222.

- ^ Eastland, pp 96, 112–113.

Sabin, p 79.

O'Brien, pp 7–8.

Belknap (1994), p 222.

Walker, p 187.

Belknap, Michal, The Vinson Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy, ABC-CLIO, 2004, p 109, ISBN 978-1-57607-201-1.

Kemper, p 655. - ^ United States v. Dennis et al (183 F.2d 201) Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ Belknap (1994), p 223. Vinson quoted by Belknap.

- ^ a b c Dennis v. United States – 341 U.S. 494 (1951) Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ Killian, p 1100.

Kemper, pp 654–655. - ^ a b c O'Brien, pp 7–8

- ^ Sabin, p 84. Black quoted by Sabin.

Morgan, pp 317–318. - ^ Killian, p 1103.

Eastland, p 112. - ^ Associated Press, "Contempt Sentences Upheld For Six Who Defended 11 Communist Leaders", The Toledo Blade, March 11, 1952. Douglas quoted in article.

Full text of Douglas' opinion is at: Sacher v. United States, 343 U.S. 1 (1952). Dissenting opinion. Justia. Retrieved January 30, 2012. - ^ Rule 42(a), Fed.Rules Crim.Proc., 18 U.S.C.A.

- ^ a b c Sacher v. United States 343 U.S. 1 (1952). Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ From Sacher's majority opinion: "We are urged that these sentences will have an intimidating effect on the legal profession, whose members hereafter will decline to appear in trials where 'defendants are objects of hostility of those in power,' or will do so under a 'cloud of fear' which "threatens the right of the American people to be represented fearlessly and vigorously by counsel'."

- ^ The appeals case was United States v. Sacher, 2 Cir., 182 F.2d 416.

- ^ The initial appeal was 341 U.S. 952, 71 S.Ct. 1010, 95 L.Ed. 1374.

- ^ Sacher v. United States. Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ Sabin p 59 (the 132 were in addition to the twelve from 1949). Belknap (1994) p 226 (126 of the 132 were conspiracy charges, 6 or 7 were membership clause charges).

- ^ a b c d e Belknap (1994), p 225–226.

- ^ Edson, Peter, "New Anti-Red Laws Requested", Lawrence Journal-World, July 15, 1954, p 4.

Navasky, p 33.

Belknap (1994) p 225. - ^ Other CPUSA members indicted included: Robert Klonsky (Philadelphia); and Alexander Bittelman, Alexander Trachtenberg, V. J. Jerome, and Betty Garrett (New York).

- ^ Sabin, pp 47–48.

- ^ Sabin, p 48.

Auerbach , p 245–248.

Rabinowitz, Victor, A History of the National Lawyers Guild: 1937–1987, National Lawyers Guild Foundation, 1987, p 28. - ^ Auerbach, p 248.

- ^ Auerbach, p 249.

- ^ Navasky, p 37.

- ^ Brown, Sarah Hart, Standing Against Dragons: Three Southern Lawyers in an Era of Fear, LSU Press, 2000, pp 21–22, ISBN 978-0-8071-2575-5.

Navasky, p 37. - ^ a b c d Sabin, pp 49–50.

- ^ The California defendants challenged their $50,000 bail ($573,684 in 2023 dollars) as excessively high, and won in the Stack v. Boyle 342 U.S. 1 (1951) Supreme Court case.

- ^ Oshinsky, David M., A Conspiracy So Immense: the World of Joe McCarthy, Oxford University Press, 2005, p 149, ISBN 978-0-02-923490-7 (discusses Budenz's income, which includes revenue from lectures and books, as well as compensation from the government for testifying).

Navasky, pp 33, 38.

Sabin, pp 62–63. - ^ Starobin, p 208.

Levin, p 1488. - ^ Belknap (2001), p 869 (defines the term "Red Monday"; on that day, a companion case, Watkins v. United States, was also decided).

Sabin, p 10.

Parker, Richard A. (2003). "Brandenburg v. Ohio". In Parker, Richard A. (ed.). Free Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives on Landmark Supreme Court Decisions. University of Alabama Press. pp. 145–159. ISBN 978-0-8173-1301-2. - ^ Yates v. United States, 354 U.S. 298 (1957) Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ In a concurring opinion Justice Black wrote: "Doubtlessly, dictators have to stamp out causes and beliefs which they deem subversive to their evil regimes. But governmental suppression of causes and beliefs seems to me to be the very antithesis of what our Constitution stands for. The choice expressed in the First Amendment in favor of free expression was made against a turbulent background by men such as Jefferson, Madison, and Mason – men who believed that loyalty to the provisions of this Amendment was the best way to assure a long life for this new nation and its Government.... The First Amendment provides the only kind of security system that can preserve a free government – one that leaves the way wide open for people to favor, discuss, advocate, or incite causes and doctrines however obnoxious and antagonistic such views may be to the rest of us." – Black quoted by Mason, Alpheus Thomas, The Supreme Court from Taft to Burger, LSU Press, 1979, pp 37, 162, ISBN 978-0-8071-0469-9. Original decision: Yates v. United States, 354 U.S. 298 (1957). Justia. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ Killian, p 1100.

Redish pp 103–105. - ^ Patrick, John J.; Pious, Richard M., The Oxford Guide to the United States Government, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp 722–723, ISBN 978-0-19-514273-0.

- ^ a b Belknap, Michal, "Communism and Cold War", in Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court, Oxford University Press, 2005, p 199, ISBN 978-0-19-517661-2.

- ^ a b Noto v. United States 367 U.S. 290 (1961) Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

The preceding federal appeals case, which upheld the conviction, was United States v. John Francis Noto, 262 F.2d 501 (2d Cir. 1958) - ^ a b c d Konvitz, "Noto v. United States", p 697: "There must be substantial evidence, direct or circumstantial, of a call to violence 'now or in the future' that is both 'sufficiently strong and sufficiently persuasive' to lend color to the 'ambiguous theoretical material' regarding Communist party teaching ... and also substantial evidence to justify the reasonable inference that the call to violence may fairly be imputed to the party as a whole and not merely to a narrow segment of it."

- ^ Noto v. United States – 367 U.S. 290 (1961) Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ Scales was initially convicted in 1955, but the sentence was overturned on appeal due to procedural mistakes by the prosecution; and he was retried in 1958. The 1957 reversal is Scales v. U. S., 355 U.S. 1, 78 S.Ct. 9, 2 L.Ed.2d 19 FindLaw. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Robert Justin, Political Repression in Modern America, (University of Illinois Press, 1978, 2001) p.417, ISBN 978-0-252-06964-2. Other CPUSA leaders, such as Noto, were convicted under the membership clause, but Scales was the only one whose conviction was not overturned on appeal.

- ^ Scales v. United States, 367 U.S. 203 (1961), Oyez. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ The federal appeals case preceding the Supreme Court appeal was 260 F.2d 21 (1958).

- ^ Willis, Clyde, Student's Guide to Landmark Congressional Laws on the First Amendment, Greenwood, 2002, p 47, ISBN 978-0-313-31416-2.