Sidney Finkelstein

Sidney Finkelstein | |

|---|---|

| Born | Sidney Walter Finkelstein July 4, 1909 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 14, 1974 (aged 64) Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | cultural critic, author |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | City College of New York, New York University |

| Alma mater | Columbia University |

| Genre | Music |

| Subject | Jazz |

| Years active | 1930s-1973 |

| Notable works | Jazz: A People's Music (1948), How Music Expresses Ideas (1952) |

| Website | |

| scua | |

Sidney Finkelstein (1909–1974) was an American cultural critic with wide-ranging interests in literature, music and fine arts, which he analyzed from a Marxist perspective. His area of particular expertise was popular music: its history, and the relationship between music and society. His best-known books include Jazz: A People's Music (1948), How Music Expresses Ideas (1952), and Composer and Nation (1960).[1] Along with Charles Seeger (father of Pete Seeger), Finkelstein is considered "one of two American Marxist musical theoreticians of consequence."[2][3] He has also been compared to British jazz writer "Francis Newton," pseudonym for British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawn.[4]

Background

[edit]Sidney Walter Finkelstein was born on July 4, 1909 in Brooklyn, New York. In 1929, he received a BA from City College of New York. In 1932, he received an MA from Columbia University.

He served in the military in World War II. In 1955, he received a second MA from New York University,[1][3] with his thesis written on Pablo Picasso.[5]

Career

[edit]

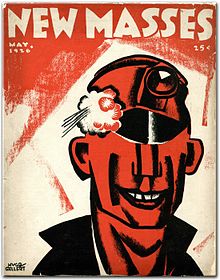

In a retrospective about him, Finkelstein was described as "a former newspaper writer turned Marxist arts critic",[2] which succinctly captures the arc of his career. In the 1930s, while working for the U.S. Postal Service, he became a book reviewer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. In the 1940s, he was hired by the New York Herald Tribune as a music reviewer. He meanwhile started contributing essays on the history and theory of art to leftist publications including New Masses and its successor Masses & Mainstream, where he remained until its close in 1963.[1][3][6] In the late 1940s, he began writing a series of books on art, the royalties from which were his principal source of income.[7]

In 1951, he joined the staff of Vanguard Records, a New York record label known for its recordings of jazz and classical music.[1][3] He worked at Vanguard until 1973, mostly writing liner notes on their classical LPs.

For many years, Finkelstein was an active member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), serving as the Party's musical and cultural theoretician. He applied the doctrine of socialist realism in his analysis of art, as evidenced by his first book, Art and Society (1947), which argued that the arts evolved over the centuries in response to the changing needs of audiences.[8] Because his books started to appear just as the Second Red Scare intensified, Michael Denning has suggested that Finkelstein's works "received—and continue to receive—far less attention than the Marxist works of the 1930s, despite the fact that Finkelstein is a far more interesting Marxist critic than [Mike] Gold, [Joseph] Freeman, [Granville] Hicks, or [V.F.] Calverton."[9]

In one of his last essays, "Beauty and Truth", Finkelstein wrote that art at its best seeks to "humanize reality":

A work of art is a man-created structure, using language, shape-making, musical sounds, or any other socially created means for exploring inner and outer reality, which crystallizes a stage in the humanization of reality. As such it becomes a social possession and a means for educating and transforming people in their ability to respond to the world about them.[10]

HUAC investigation

[edit]In April 1957, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) held hearings in New York City about the Metropolitan Music School, which HUAC claimed was "controlled by identified Communists."[11] The committee questioned the school's director, Lilly Popper, and several board members who all invoked the Fifth Amendment when asked about their Communist Party affiliation, which was banned at the time under the Smith Act.[12]

The HUAC then questioned Finkelstein.[13] The committee identified him as "cultural spokesman for the Communist Party" and a member of the Metropolitan Music School's board of directors. He confirmed he'd been a board member from 1955-57 and had taught a Music Appreciation class at the school.[14] When asked about Communist Party affiliation, he too invoked the Fifth Amendment.[15]

The HUAC inquisitors were particularly interested in Finkelstein's connection with the Jefferson School of Social Science, which they classified as subversive according to the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations. When Congressman Richard Arens asked Finkelstein where else he had taught besides the Metropolitan Music School (seeking information about the Jefferson School), Finkelstein replied:

I decline to answer that question on the basis of my—well, I decline for three reasons: One is that, observing the proceedings up to now, I believe that these proceedings are an attempt to smear a school without the slightest interest in what that school is teaching or doing. I think this is an un-American procedure, especially as it refers to a school. I think it is an interference with the search for truth, which is essential to the operation of a school. So, on principle, I would not want to cooperate with such a procedure. My second reason is the fact that I think that this committee's operations are an invasion of the right of free speech guaranteed by the first amendment of the Constitution, where Congress is prohibited to legislate. My third reason is my rights not to be a witness against myself as guaranteed by the fifth amendment to the Constitution.[7]

At one point in his testimony, Congressman Clyde Doyle quoted the following passage from Finkelstein's writings: "The FBI has its paid informers everywhere, and almost any lodge, church, political meeting, or labor organization may be victimized by these peeping toms." Rep. Doyle then asked, "Where in God's name would our Nation be if the FBI wasn't able to get patriotic American citizens to go into these organizations in which Commies, crooks, cheats, and traitors infiltrate? Would you tell me where our Nation would land if we did not have the FBI?" Finkelstein responded, "The Nation might be reduced to the terrible procedure of having to jail people for crimes, only if it found that they actually committed them or found that they did something criminal, not just thinking."[16]

Soon after his HUAC testimony, Finkelstein's name was listed in three issues of the anti-communist newsletter Counterattack. The newsletter labeled him the "Daily Worker music critic" and a member of the board of directors of the Metropolitan Music School.[17] In 1964, the Christian publication The Weekly Crusader cited the 1957 HUAC hearings when characterizing Finkelstein as "cultural spokesman for the communist conspiracy":

...on October 2, 1920, Lenin informed the conspirators that they must re-work "the culture created by the whole development of mankind..." He told these young communists that "only by re-working this culture, is it possible to build proletarian (communist) culture..." Music, of course, is misused as a part of this communist "cultural" war against mankind. In a book published by the communist publishing house, International Publishers, during 1952, and entitled How Music Expresses Ideas, the author Sidney Finkelstein used the above quote by Lenin in relation to music.[18]

Personal life and death

[edit]Finkelstein was a private man. Even his close friends Phillip Bonosky and Herbert Aptheker did not know whether he had a family of his own.[5]

Daniel Rosenberg was a young jazz enthusiast who had an opportunity to meet with Finkelstein several times in the early 1970s. In a tribute piece written decades later, Rosenberg noted that Finkelstein's house in Brooklyn had floor-to-ceiling books, along with thousands of 78s and LPs. They listened together to Lester Young, Charlie Parker and other favorite jazz artists, and Finkelstein lent Rosenberg several records.[5]

Sidney Finkelstein was found dead of a stroke in his Brooklyn home at age 64 on January 14, 1974.[1] He had two brothers who survived him.[3]

Works

[edit]Finkelstein wrote nearly a dozen books and scores of articles:[3]

- Books

- Art and Society (1947)[8]

- Jazz: A People's Music (1948)[19]

- Jazz (1951)[20]

- How Music Expresses Ideas (1952)[21]

- Realism in Art (1954)[22]

- Charles White: Ein Künstler Amerikas (1955)[23]

- Composer and Nation: The Folk Heritage of Music (1960)[24]

- Existentialism and Alienation in American Literature (1965)[25]

- Sense and Nonsense of McLuhan (1968)[26]

- The Young Picasso (1969)

- Who Needs Shakespeare? (1973)[27]

- Contributions

- James Fenimore Cooper: Short Stories from His Novels (1970)[28]

- Selected Articles

- "How Marx and Engels Looked at Art," New Masses (1947)[29]

- "The Folk Song is Back to Stay," Worker Magazine (6 March 1949)

- "Answering Attack on Marxism – New York City," Daily Worker (14 October 1949)[13]

- "Charles White's Humanist Art," Masses & Mainstream (1953)[30]

- "How Art Began," Masses & Mainstream (1954)[31]

- "Notes on Contemporary Music," Political Affairs (1957)[32]

- "Ezra Pound's Apologists," Mainstream (1961)[33]

- "Beauty and Truth," Weapons of Criticism (1976)[10]

Legacy

[edit]Finkelstein is still regarded as an expert resource on the origins and development of jazz.[34] In 2015, The New York Times cited Finkelstein in an article on the 1942 jazz-themed film Syncopation directed by William Dieterle.[35] In 2018, Culture Matters wrote an appreciation of him, which concluded: "Analyses of jazz and society will therefore run aground if they fail to consult Jazz: A People’s Music."[5] Finkelstein's analysis of the pioneering African-American painter Charles White has continued to receive mention up through the 2020s.[36]

The University of Massachusetts Amherst houses Finkelstein's papers, which include correspondence with publisher Angus Cameron, artist Rockwell Kent, playwright and screenwriter John Howard Lawson, educator Howard Selsam, and music composer Virgil Thomson.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Finkelstein, Sidney Walter, 1909-1974". University of Massachusetts Amherst. 1947. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ a b Richard A. Reuss; JoAnne C. Reuss; Ralph Lee Smith; Ronald C. Cohen, eds. (2000). American Folk Music and Left-wing Politics, 1927-1957. Scarecrow Press. pp. 51 (consequence), 242 (turned), 269 (turned). ISBN 9780810836846. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sidney Finkelstein, Music Critic, Dead". New York Times. 15 January 1974. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Godel, Greg (22 August 2017). "Coltrane's revolutionary musical journey". Culture Matters. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Rosenberg, Daniel (12 January 2018). "Sidney Finkelstein: an appreciation of the great Marxist cultural critic". Culture Matters. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Peter Brooker; Andrew Thacker, eds. (2009). The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume II: North America 1894-1960. Oxford University Press. p. 854. ISBN 9780810836846. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ a b HUAC 1957, p. 673.

- ^ a b Finkelstein, Sidney (1947). Art and Society. New York: International Publishers. ISBN 978-0-598-64123-6.

- ^ Denning, Michael (2010). The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. Verso. p. 458. ISBN 978-1844674640.

- ^ a b Finkelstein, Sidney (1976). "Beauty and Truth". In Rudich, Norman (ed.). Weapons of Criticism: Marxism in America and the Literary Tradition. Ramparts Press. pp. 51–73. ISBN 0878670572.

- ^ HUAC 1957, p. 607.

- ^ HUAC 1957, p. 615.

- ^ a b HUAC (1957). "Testimony of Sidney Finkelstein, accompanied by counsel Mildred Roth". Investigation of Communism in the Metropolitan Music School, Inc., and Related Fields, Part 1. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 672.

- ^ HUAC 1957, p. 672.

- ^ HUAC 1957, p. 674.

- ^ HUAC 1957, p. 678.

- ^ The New Counterattack: Facts to Combat Communism. American Business Consultants. 1954. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ The Weekly Crusader, Volume 5. Christian Crusade. 1964. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (2019) [First published 1948]. "illustrations by Jules Halfant, new foreword by Geoffrey Jacques". Jazz: A People's Music. International Publishers. ISBN 978-0717807611.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1951). Jazz. G. Hatje. LCCN 53023723. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1970) [First published 1952]. How Music Expresses Ideas. International Publishers. ISBN 978-0717800957 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1954). Realism in Art. International Publishers. LCCN 54012924. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1955). Charles White: Ein Künstler Amerikas. Verlag d. Kunst. p. 67. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1960). "foreword and afterword by Carmelo Peter Comberiati". Composer and Nation: The Folk Heritage of Music. International Publishers. LCCN 60009947. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1965). Existentialism and Alienation in American Literature. International Publishers. LCCN 65016394. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1968). Sense and Nonsense of McLuhan. International Publishers – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1973). Who Needs Shakespeare?. International Publishers. LCCN 79018760. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Cooper, James Fenimore (1970). "Excerpted and with an Introduction by Sidney Finkelstein". James Fenimore Cooper: Short Stories from His Novels. International Publishers. LCCN 79018760.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (2 December 1947). "How Marx and Engels Looked at Art" (PDF). New Masses. Vol. 65, no. 2 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (February 1953). "Charles White's Humanist Art". Masses & Mainstream. Vol. 6.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (June 1954). "How Art Began". Masses & Mainstream. pp. 15–26.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (March 1957). "Notes on Contemporary Music" (PDF). Political Affairs. Retrieved 28 August 2024 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (January 1961). "Ezra Pound's Apologists". Mainstream. 14: 19–34.

- ^ Denning 2010, pp. 459–460.

- ^ Hoberman, J (27 February 2015). "William Dieterle's 'Syncopation' on DVD: Bending Notes and Jazz History". The New York Times.

- ^ Harris, Serafina (4 July 2020). "Charles White and the Purpose of Education". Organization for Positive Peace.

External links

[edit]- University of Massachusetts Amherst - Sidney Finkelstein Papers

- Library of Congress catalog

- Communism and Jazz (Side B)

- Photo of Sidney Finkelstein

- Charles White: ein Künstler Amerikas: Art historian Eddie Chambers discusses Finkelstein's 1955 German-language book that first brought scholarly attention to White.