Siddington, Gloucestershire

| Siddington | |

|---|---|

St. Peter's Church, Siddington | |

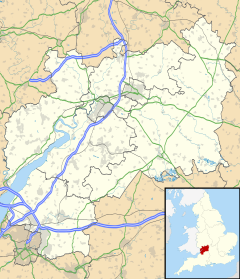

Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Area | 3.33 sq mi (8.6 km2) [1] |

| Population | 1,249 [1] |

| • Density | 375/sq mi (145/km2) |

| • London | 79 mi (127 km) |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Cirencester |

| Postcode district | GL7 |

| Dialling code | 01285 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Siddington Parish Council |

Siddington is a village and civil parish in Gloucestershire, England. It is located immediately south of Cirencester. At the 2011 United Kingdom Census, the parish had a population of 1,249.

There is evidence of Neolithic inhabitation of the area. Situated adjacent to Ermin Way, the Roman road connecting present-day Gloucester and Silchester, Siddington has multiple examples of Romano-British settlements. The village was mentioned in the Domesday Book, and parts of the church are Norman. During the Industrial Revolution, the Thames and Severn Canal was built through the parish, followed by the Cirencester branch line and the Swindon and Cheltenham Extension Railway in the 1840s and 1880s respectively.

Siddington is located near the Cotswolds AONB, and parts of the Cotswold Water Park SSSI are within the parish.

History

[edit]Pits, sherds, and flint are evidence of Neolithic inhabitation of the Siddington area. Beaker pottery found in the area suggests Early Bronze Age activity, and various earthworks are evidence of middle Bronze Age and Iron Age use of the area.[2] Ermin Way, the Roman road connecting Glevum (Gloucester) to Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) via Corinium (Cirencester) forms part of the parish's north-eastern border.[3] Romano-British settlements existed near the west border and at the south of the parish. The latter settlement is evidenced by pottery and building debris, as well as discoveries of a well and a coin of Constantius II.[3] Excavation of a third Romano-British settlement, near Ermin Way, uncovered a sherd from a situla dating from the Iron Age.[3]

The name "Siddington" is derived from the Old English sūð in tūn, meaning "south in the farm [or] settlement".[4] Siddington was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as comprising 46 households, putting it in the top fifth of English settlements as regards population. Additionally, it was at that time recorded as lying within the hundred of Cirencester and the county of Gloucestershire. Landowners of Siddington following the Norman Conquest included Godric, Leofwin, and Emma (wife of Walter de Lacy).[5] Alternative spellings have included "Sudintone" and "Suintone",[6] and in the Domesday Survey of 1086, the name "Suditone" was used. At this time, Siddington was recorded as having landowners including Roger of Lacy, Hascoit Musard, Humphrey the Chamberlain, and William fitzBaderon.[5][7] The survey showed that Siddington had at least 17 villagers, 18 smallholders, 13 slaves, and 2 priests, as well as a mill and 20 acres (8.1 ha) of meadowland.[5] Ridge and furrow patterns have suggested agricultural use of the higher land during the Medieval period.[2] Geoffrey of Langley inherited the Siddington estate in the 1220s.[8]

In the 1780s, during the Industrial Revolution, the Thames and Severn Canal was constructed through the parish, and a flight of four locks was built to begin the canal's descent from its summit pound towards the River Thames; the locks brought the canal down a total of 39 ft (12 m).[a][9] Immediately west of the top lock was a wharf and basin where a short canal arm led north into Cirencester.[10] Railways arrived in Siddington in 1841, when the Cirencester branch line opened between Cirencester Town and Kemble. The line did not serve Siddington until 1960, however, when Park Leaze Halt opened across the Kemble parish border.[11] In 1883, the Swindon and Cheltenham Extension Railway, later becoming the Midland and South Western Junction Railway (MSWJR), opened between Cirencester Watermoor and Swindon,[12] crossing the canal between the third and fourth locks in the flight.[13] As with the Cirencester branch line, the MSWJR did not give Siddington its own station; the nearest stops on the line were Cerney and Ashton Keynes and the Cirencester terminus itself, the latter being nearer at 1 mi (1.6 km) from the village.[14]

John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870–72) described how Siddington parish covered 1,950 acres (790 ha), had a property value of £2,777 (equivalent to £313,186 in 2023), and a population of 474 within 110 households. The manor was part of the Bathurst estate,[15] and as well as the parish church, the village had an independent chapel.[16] John George Bartholomew's Gazetteer of the British Isles, published in 1887, noted the size of the parish as 2,317 acres (938 ha) and showed that the population had risen to 481.[17]

The canal was abandoned in 1927,[18] although through-passage of the Sapperton Tunnel had become near impossible after the 1910s when multiple roof collapses had occurred.[19] Parts of the canal bed in Siddington were later infilled and some areas built upon.[20] The railways were removed in the 1960s; while the decline and closure of the MSWJR preceded it,[21] the Cirencester Branch was a casualty of the Beeching Axe of the early 1960s.[22]

Governance

[edit]As a civil parish, Siddington has a parish council formed of nine councillors as well as a chair and vice-chair.[23] The parish is within the catchment of Cotswold District Council.[24]

Siddington forms part of the Siddington and Cerney Rural ward,[25] itself part of the Cotswolds constituency.[25] Since 1992, the MP representing the constituency has been Geoffrey Clifton-Brown.[26] Historically, Siddington was in the hundred of Crowthorne and Minety.[16]

Geography

[edit]Topography

[edit]

Siddington is located within the catchment of the River Thames;[27] the River Churn, the farthest tributary from the river mouth, flows through the parish.[28] The Environment Agency operates a monitoring station near the site of Siddington Mill. Between 2009 and 2012 the classification of fish in the river was "good" or "moderate",[29] and between 2013 and 2016[b] this fluctuated between "bad", "poor", and "moderate".[30]

The Cotswold Water Park SSSI is partly within the parish,[31] and the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty is less than 1 mi (1.6 km) northwest of Siddington.[24] Part of the Kemble & Ewen Special Landscape Area is within the western extremities of the parish.[24] One designated brownfield site is within the parish, on its east border.[24]

Situated on the edge of the Cotswolds, a contour line at 362 ft (110 m) AOD runs through the parish.[32][33] Here, the Thames and Severn Canal follows the land to act as a contour canal on its summit pound west of the Siddington Locks.[34]

Geology

[edit]The bedrock geology of Siddington includes the Cornbrash Formation, Forest Marble Formation, Oxford Clay Formation, and the Kellaways Formation.[35] Superficial deposits include Hanborough gravel and alluvium.[35]

Boundaries

[edit]The parish of Siddington covers 862.34 ha (2,130.9 acres).[1] It is bordered to the north by Cirencester, to the east by Preston and South Cerney, to the south by Somerford Keynes, and to the west by Kemble.[36] The River Churn forms part of Siddington's boundary with South Cerney, as does the former RAF South Cerney (now the Duke of Gloucester Barracks).[25] Ermin Way (now followed by the course of the A419) is the parish's north east border.[25]

Climate

[edit]The nearest Met Office weather station is at the Royal Agricultural University in Cirencester.[37] The average summer high temperature is 22.28 °C (72.10 °F), and the average winter low is 1.23 °C (34.21 °F). The average minimum rainfall is 55.53 mm (2.186 in) per month, with an annual average of 132 rainy days.[38]

| Climate data for Royal Agricultural University, Cirencester (1991–2020 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.37 (45.27) |

8.01 (46.42) |

10.67 (51.21) |

13.66 (56.59) |

16.84 (62.31) |

19.77 (67.59) |

22.28 (72.10) |

21.82 (71.28) |

18.93 (66.07) |

14.48 (58.06) |

10.32 (50.58) |

7.69 (45.84) |

14.35 (57.83) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.23 (34.21) |

1.26 (34.27) |

2.62 (36.72) |

4.15 (39.47) |

7.00 (44.60) |

9.70 (49.46) |

11.67 (53.01) |

11.57 (52.83) |

9.60 (49.28) |

7.01 (44.62) |

3.76 (38.77) |

1.62 (34.92) |

5.96 (42.73) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 82.93 (3.26) |

58.13 (2.29) |

55.53 (2.19) |

55.56 (2.19) |

64.07 (2.52) |

59.08 (2.33) |

58.95 (2.32) |

67.25 (2.65) |

58.42 (2.30) |

84.08 (3.31) |

88.77 (3.49) |

89.82 (3.54) |

822.59 (32.39) |

| Average rainy days | 13.13 | 10.60 | 10.27 | 10.30 | 10.19 | 9.17 | 8.92 | 10.63 | 9.47 | 12.37 | 13.52 | 13.27 | 131.84 |

| Source: [38] | |||||||||||||

Settlements

[edit]The parish has three main areas of settlement – the nucleated village centre of Siddington, the small outlying settlement of Upper Siddington, and part of the linear expansion of Cirencester at North Siddington.[25][39]

Demography

[edit]The 2011 United Kingdom Census reported that the parish had a population of 1,249. Most residents (approximately 60%) live in Siddington and Upper Siddington, and roughly 32% reside in North Siddington on the Cirencester outskirts.[40] Of the population, 48% were recorded as male and 52% female.[1] The median age of Siddington residents is 48.[1] Ethnically, Siddington is 96.3% White British, with a majority of respondents reporting their national identity as English.[1] Approximately 74% of residents are Christian, and 25% claim to follow no religion or did not report their religious beliefs to the census. Fewer than 1% of the population follow Buddhism and Hinduism.[1]

| Historical population of Siddington | |||||||||||

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 325 | 321 | 349 | 409 | 469 | 502 | 474 | 520 | 481 | 571 | 501 |

| Year | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

| Population | 524 | 520 | 501 | [c] | 466 | 659 | 829 | 961 | |||

| 1811–1851, 1871–1961;[42] 1861;[43] 1871;[44] 2001–2011[45] | |||||||||||

Economy

[edit]Early industries in Siddington include brickmaking; the presence of clay pits and quarries is marked on Ordnance Survey maps of c. 1888–1913.[46] Siddington formerly had a water-driven corn mill on the Churn, although this was derelict by the 1950s.[47][48] A windmill was built in the late 18th century to grind corn; the Mills Archive does not note its operational dates[49] but its Grade II listing shows that by the 1980s it was "semi-derelict" and had become known as the Round House.[50]

Of the working population of Siddington, the most common employment sector is the wholesale and retail trade.[d][1] The next most common industries are manufacturing, social work, education, and construction.[1]

Within the parish, 18.5% of all businesses lie within the professional, scientific, and technical services sector. Construction accounts for 8.6% of businesses, and 7.4% of companies are business administration and support.[51] The number of VAT registered companies per 10,000 working age population is above both the national average and that of Gloucestershire as a whole.[51]

Amenities in the village include a branch of the Post Office[52] and a public house.[53]

Landmarks

[edit]

Twenty listed buildings are in the village,[54] including the church,[55] the old school house,[56] the Greyhound Inn,[57] the brick arch canal bridge,[58] and the Round House.[50] Scheduled monuments in the parish include the tithe barn at Church Farm[59] and part of the Romano-British settlement near Chesterton.[60]

Siddington has a war memorial within St Peter's Church. It is a plaque dedicated to 13 men killed in the First World War.[61] Similarly, the village hall was built in 1921 as a memorial hall to commemorate the war. The Earl Bathurst gave the plot of land to the village for the hall's construction, and recycled stone from an old nearby barn was used for the building.[62]

Transport

[edit]

The parish is served by Stagecoach West bus services 51 (Swindon–Cirencester)[63] and C62 (Malmesbury–Cirencester College).[64] Since the removal of the two railway lines in the parish in the 1960s, the nearest railway station has been Kemble.[21][22] The Cotswold Canals Trust aims to restore the Thames and Severn Canal (albeit not the Cirencester Arm[65]) which would bring the lock flight through Siddington back in to full operation.[66][67]

Education

[edit]Siddington Church of England Primary School, located in the north west of the parish, is a co-educational primary school for students aged 5 to 11.[68] Its three most recent Ofsted inspections – in 2010, 2013, and 2017 – have returned "satisfactory" or "good" ratings.[69][70][71] In 2018, the school adopted academy status and became part of the Corinium Education Trust along with Cirencester Deer Park School and the primary schools in Kemble and Chesterton.[72]

Religious sites

[edit]

The parish church, in the Diocese of Gloucester, is dedicated to St Peter.[16] The church is originally Norman, and was extended in c. 1470.[55] It underwent restoration by Henry Woodyer in 1864; at this point the church tower was added.[55] Of the Norman church, three original features remain – the south doorway, the font, and the chancel arch.[73] The tower has a peal of six bells,[73] all of which were cast by John Warner & Sons in 1879:[74]

- 3 long cwt 2 qr (390 lb or 180 kg)

- 4 long cwt (400 lb or 200 kg)

- 4 long cwt 2 qr (500 lb or 230 kg)

- 4 long cwt 3 qr (530 lb or 240 kg)

- 6 long cwt (700 lb or 300 kg)

- 7 long cwt 1 qr (810 lb or 370 kg); tenor in B♭

A church dedicated to St Mary was demolished in c. 1778 after the amalgamation of its parish with that of St Peter's.[75] Unlike St Peter's, which was overseen by a vicar, St Mary's had a rector.[16] In 1928, a benefice was formed between Siddington and Preston; today, the Churnside Benefice covers South Cerney with Cerney Wick, Siddington, and Preston.[76]

A Quaker burial ground was established in Siddington in 1660, although it is now closed.[77] John Roberts a Quaker humourist who had been born in Siddington, was interred within the cemetery.[78]

Sport

[edit]Siddington Cricket Club was first mentioned in the 1850s, playing home games at the village recreation ground until the club folded in the 1950s. It was re-formed in 2017, based in Ampney Crucis.[79]

Siddington Football Club play their home games on the village playing field. The first team competes in Cirencester and District League.[80]

Notable people

[edit]- Laurence Llewellyn-Bowen, interior designer and TV personality, lives in the village[81]

- Phoebe Paterson Pine, Paralympic archer, was born in Siddington[82]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Each lock had a depth of 9 ft 9 in (2.97 m)[9]

- ^ Environment Agency data from 2016 onwards has not been published

- ^ No census was conducted in 1941 due to World War II[41]

- ^ The Office for National Statistics includes "repair of motor vehicles and motor cycles" in this category

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Siddington Parish Local Area Report". Nomis. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ a b Milbank, Danielle; Wallis, Sean; Ford, Steve (2011). "Dryleaze Farm, Siddington, Gloucestershire Extraction Phases 1 and 2" (PDF). Thames Valley Archaeological Services: 1 pdf file. doi:10.5284/1030477. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Siddington". www.british-history.ac.uk. British History Online. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Key to English Place-names". kepn.nottingham.ac.uk. University of Nottingham. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Siddington in the Domesday Book. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Transactions". Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. 81: 133. 1962.

- ^ "Siddington [House]". opendomesday.org. Open Domesday. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Coss, Peter R. (1991). Lordship, knighthood, and locality : a study in English society, c. 1180-c. 1280. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780521402965.

- ^ a b Household, Humphrey (1969). The Thames & Severn Canal. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. p. 224. ISBN 9781445625997.

- ^ Bird, Nick. "Siddington Top Lock". www.cotswoldcanals.net. Cotswold Canals in Pictures. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The directory of railway stations : details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present. Sparkford: Stephens. p. 181. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

- ^ Oakley, Michael (2003). Gloucestershire railway stations. Wimborne: Dovecote. ISBN 1-904349-24-2.

- ^ Bird, Nick. "Site of Midland & SWJ Railway Bridge, Siddington". www.cotswoldcanals.net. Cotswold Canals in Pictures. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Explore georeferenced maps - Map images - National Library of Scotland". maps.nls.uk. Archived from the original on 6 October 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "History of Siddington, in Cotswold and Gloucestershire". visionofbritain.org.uk. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Siddington, Gloucestershire Family History Guide - Parishmouse Gloucestershire". parishmouse.co.uk. Parishmouse. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Descriptive Gazetteer Entry for Siddington". visionofbritain.org.uk. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Bagwell, Philip Sidney (1988). The transport revolution. London: Routledge. p. 272. ISBN 9781134985012.

- ^ Bird, Nick. "Sapperton Canal Tunnel". www.cotswoldcanals.net. Cotswold Canals in Pictures. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Bird, Nick. "Cotswold Canals Infilled Canal". www.cotswoldcanals.net. Cotswold Canals in Pictures. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b Barnsley, M P. "Midland & South Western Junction Railway". hmrs.org.uk. Historical Model Railway Society. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Chesterton Lane Halt". disused-stations.org.uk. Disused Stations. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Parish Council Members". www.siddingtonparishcouncil.org.uk. Siddington PC. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d "My Maps". my.cotswold.gov.uk. Cotswold District Council. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Election Maps". www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk. Ordnance Survey. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown". members.parliament.uk/. UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Thames Upper Operational Catchment | Catchment Data Explorer". environment.data.gov.uk. Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Churn (Baunton to Cricklade) | Catchment Data Explorer". environment.data.gov.uk. Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "THAMES/UPPER THAMES/RIVER CHURN/SIDDINGTON/ Monitoring Site | Catchment Data Explorer". environment.data.gov.uk. Environment Agency. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "THAMES/UPPER THAMES/RIVER CHURN/SIDDINGTON/ Monitoring Site | Catchment Data Explorer". environment.data.gov.uk. Environment Agency. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Sites of Special Scientific Interest (England)". naturalengland-defra.opendata.arcgis.com. Defra. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Viner, David James (2002). The Thames & Severn canal : history & guide. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. p. 14. ISBN 9780752417615.

- ^ "England topographic map, elevation, relief". topographic-map.com. Topographic Maps. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Bird, Nick. "Locks of the Cotswold Canals". www.cotswoldcanals.net. Cotswold Canals in Pictures. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Geology of Britain Viewer". mapapps.bgs.ac.uk. British Geological Survey (BGS). Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Gloucestershire Parish Map" (PDF). gloucestershire.gov.uk. Gloucestershire County Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Synoptic and climate stations". metoffice.gov.uk. Met Office. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Cirencester (Gloucestershire) UK climate averages". metoffice.gov.uk. Met Office. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Improvements and Future Plans | Siddington Village Hall – Gloucestershire". siddingtonvillagehall.co.uk. Siddington Village Hall. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "History". siddington.com. Siddington Village. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Census records". The National Archives. The National Archives. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Population Statistics". visionofbritain.org.uk. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Census of England and Wales for the Year 1861 ...: Numbers and distribution of the people". Census of England and Wales for the Year 1861, Great Britain. 1. Census Office: 447. 1862.

- ^ "Digest of the English Census of 1871". Census of England and Wales for the Year 1871, Great Britain. 1. Census Office: 105. 1872.

- ^ Brinkhoff, Thomas. "Siddington". citypopulation.de. City Population. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "OS Six Inch, 1888–1913 (Siddington parish, Gloucestershire)". maps.nls.uk. National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 6 October 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Item EMGC-04-17-36 - Siddington Mill". catalogue.millsarchive.org. Mills Archive. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Barber, Alistair (November 1991). "Siddington Tithe Barn, Gloucestershire. Archaeological Excavation" (PDF). cotswoldarchaology.co.uk. Cirencester: Cotswold Archaeological Trust. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Tower mill, Siddington". millsarchive.org. The Mills Archive. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ a b Historic England. "THE ROUND HOUSE (1090069)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Local Insight profile for 'Siddington CP' area" (PDF). gloucestershire.gov.uk. OCSI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Siddington Post Office | Branch Finder". www.postoffice.co.uk. Post Office. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "The Greyhound Inn, Siddington". www.wadworth.co.uk. Wadworth. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Map Search | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Historic England. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Historic England. "CHURCH OF ST PETER (1340986)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "SCHOOL HOUSE (1153896)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "THE GREYHOUND (1090071)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "UPPER SIDDINGTON BRIDGE (1090036)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "Tithe barn, Siddington (1003445)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Harrison, David (2015). "Land south-east of Chesterton Farm, Cirencester, Gloucestershire: Geophysical Survey" (PDF). Archaeological Services WYAS (1759): 1. doi:10.5284/1052844. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "St Peters Church Tablet WW1". Imperial War Museums. Imperial War Museums. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "About | Siddington Village Hall – Gloucestershire". siddingtonvillagehall.co.uk. Siddington Village Hall. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "51 from Swindon to Cirencester connecting to Cheltenham" (PDF). stagecoachbus.com. Stagecoach West. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "C62 Route: Schedules, Stops & Maps - Cirencester (Updated)". moovitapp.com. Moovit. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Bird, Nick. "Basin & Wharf House, Cirencester Arm". www.cotswoldcanals.net. Cotswold Canals in Pictures. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Bird, Nick. "Cotswold Canals Restoration Phase Map". www.cotswoldcanals.net. Cotswold Canals in Pictures. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Bird, Nick. "Restoration - The Story So Far". www.cotswoldcanals.net. Cotswold Canals in Pictures. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Siddington Church of England Primary School - GOV.UK". www.get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Get Information about Schools. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Siddington Church of England Primary School (2010 inspection)". ofsted.gov.uk. Ofsted. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Siddington Church of England Primary School (2013 inspection)". ofsted.gov.uk. Ofsted. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Siddington Church of England Primary School (2017 inspection)". ofsted.gov.uk. Ofsted. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "CORINIUM EDUCATION TRUST". www.get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Get Information about Schools. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ a b "History of Siddington Church". www.churnsidechurches.org.uk. Churnside Churches. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Bagley, David P. "A Ringers Guide to Towers in Gloucestershire". www.bagleybells.co.uk. Church Bells in Gloucestershire. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ Lockie, Rosemary. "St Mary's Church (Demolished), Siddington, Gloucestershire, Church History". churchdb.gukutils.org.uk. Places of Worship Database. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Churnside Benefice". www.churnsidechurches.org.uk. Churnside Churches. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Lockie, Rosemary. "Friends Burial Ground, Siddington". churchdb.gukutils.org.uk. Places of Worship Database. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Smith, Charlotte Fell; Lawrence, Edmund Tanner (1896). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 48. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ "Siddington Cricket Club". siddington.com. Siddington Village. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Siddington First | M4 KARTING CIRENCESTER & DISTRICT LEAGUE". fulltime.thefa.com. Football Association. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Joyner, Lisa (17 August 2019). "Inside Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen's stunning Cotswolds home". Country Living. Hearst. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Woodall, Phil, ed. (October 2021). "SIDDINGTON ATHLETE STRIKES GOLD IN TOKYO" (PDF). The Village News: 2.