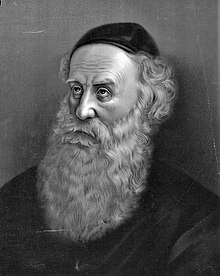

Shneur Zalman of Liadi

Shneur Zalman of Liadi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Alter Rebbe / Baal HaTanya |

| Personal | |

| Born | Shneur Zalman Borukhovich 15 September 1745 [OS: 4 September 1745] |

| Died | 27 December 1812 (aged 67) [OS: 15 December 1812] |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Spouse | Sterna Segal |

| Children | Dovber Schneuri Chaim Avraham Moshe Freida Devorah Leah Rochel |

| Parents |

|

| Jewish leader | |

| Predecessor | Dovber of Mezeritch |

| Successor | Dovber Schneuri |

| Began | gradual (late 1700s) |

| Ended | December 15, 1812 OS |

| Main work | Tanya, Shulchan Aruch HaRav, Torah Or/Likutei Torah |

| Dynasty | Chabad |

Shneur Zalman of Liadi, (Hebrew: שניאור זלמן מליאדי; September 4, 1745 – December 15, 1812 O.S. / 18 Elul 5505 – 24 Tevet 5573) commonly known as the Alter Rebbe or Baal Hatanya, was a rabbi as well as the founder and first Rebbe of Chabad, a branch of Hasidic Judaism. He wrote many works, and is best known for Shulchan Aruch HaRav, Tanya, and his Siddur Torah Or compiled according to the Nusach Ari.

Names

[edit]Zalman is a Yiddish variant of Solomon and Shneur (or Shne'or) is a Yiddish composite of the two Hebrew words "shnei ohr" (שני אור "two lights").

He is also known as Shneur Zalman Baruchovitch, using the Russian patronymic of his father Baruch,[1] and by a variety of other titles and acronyms including "Baal HaTanya VeHaShulchan Aruch'" ("Author of the Tanya and the Shulchan Aruch"), "Alter Rebbe" (Yiddish for "Old Rabbi"), "Admor HaZaken" (Hebrew for ″Our Old Master and Teacher″), "Rabbenu HaZaken" (Hebrew for "Our Old Rabbi"), "Rabbenu HaGadol" (Hebrew for "Our Great Rabbi")", "RaShaZ" (רש"ז for Rabbi Shneor Zalman), "GRaZ" (גר"ז for Ga'on Rabbi Zalman), and "HaRav" (The Rabbi, par excellence).

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Shneur Zalman was born in 1745 in the small town of Liozna, Grand Duchy of Lithuania (present-day Belarus). He was the son of Baruch,[2] who was a paternal descendant of the mystic and philosopher Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel.[3] According to Meir Perels of Prague, the Maharal was the great-great-grandson of Judah Leib the Elder who was said to have descended paternally from Hai Gaon and therefore also from the Davidic dynasty; however, several modern historians such as Otto Muneles and Shlomo Engard have questioned this claim.[4] Shneur Zalman was a prominent (and the youngest) disciple of Dov Ber of Mezeritch, the "Great Maggid", who was in turn the successor of the founder of Hasidic Judaism, Yisrael ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov.[citation needed]

He displayed extraordinary talent while still a child. By the time he was eight years old, he wrote an all-inclusive commentary on the Torah based on the works of Rashi, Nahmanides and Abraham ibn Ezra.[5]

Until the age of 12, he studied under Issachar Ber in Lyubavichi (Lubavitch); he distinguished himself as a Talmudist, such that his teacher sent him back home, informing his father that the boy could continue his studies without the aid of a teacher.[6] At the age of 12, he delivered a discourse concerning the complicated laws of Kiddush Hachodesh, to which the people of the town granted him the title "Rav".[7]

At age 15 he married Sterna Segal, the daughter of Yehuda Leib Segal, a wealthy resident of Vitebsk, and he was then able to devote himself entirely to study. During these years, Shneur Zalman was introduced to mathematics, geometry, and astronomy by two learned brothers, refugees from Bohemia, who had settled in Liozna.[8] One of them was also a scholar of the Kabbalah. Thus, besides mastering rabbinic literature, he also acquired a fair knowledge of the sciences, philosophy, and Kabbalah.[8] He became an adept in Isaac Luria's system of Kabbalah, and in 1764 he became a disciple of Dov Ber of Mezeritch. In 1767, at the age of 22, he was appointed maggid of Liozna, a position he held until 1801.[citation needed]

Parents

[edit]According to the Chabad Hasidic tradition, Shneur Zalman's father, Baruch, was a laborer who preferred to earn a living as a gardener rather than accept a post as a community rabbi or as a preacher (magid). In this tradition, Baruch was one of the disciples of Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov. However, he only occasionally joined his teacher on his legendary travels. This tradition is used to justify why Hasidic records do not refer to Baruch with a rabbinic title, claiming that Baruch was averse to any public acknowledgment of his status.[9]

Misnagdim

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Chabad (Rebbes and Chasidim) |

|---|

|

|

|

In the course of the Hasidic movement's establishment, opponents (Misnagdim) arose among the local Jewish community. Disagreements between Hasidim and their opponents included debates concerning knives used by butchers for shechita, and the phrasing of prayers, among others.[10] Shneur Zalman and a fellow Hasidic leader, Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk (or, according to the tradition in the Soloveitchik family, Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev), attempted to persuade the leader of Lithuanian Jewry, the Vilna Gaon, of the legitimacy of Hasidic practices. However, the Gaon refused to meet with them.[11]

Children and succession

[edit]Shneur Zalman's sons were Dov Ber Schneuri (who eventually succeeded him), Chaim Avraham, and Moshe. Shneur Zalman's daughters were named Freida, Devorah Leah and Rochel. Other families have lore telling that they are also descendants, but they are undocumented in existing family records.[citation needed]

Dov Ber Shneuri

[edit]Dovber Schneuri succeeded his father as Rebbe of the Chabad movement.[citation needed] At the age of 39, while studying in the city of Kremenchug, Shneur Zalman died.[12] Shneuri then moved to the small border-town of Lubavichi, from which the movement would take its name.[12] His accession was disputed by one of his father's prime students, Aharon HaLevi of Strashelye, however the majority of Shneur Zalman's followers stayed with Schneuri, and moved to Lubavichi.[12] Thus Chabad had now split into two branches, each taking the name of their location to differentiate themselves from each other.[12] He established a Yeshivah in Lubavitch, which attracted gifted young scholars. His nephew/son-in-law, Menachem Mendel of Lubavitch, headed the Yeshivah, and later became his successor.[citation needed]

Thus, while Schneuri succeeded his father as Rebbe of the Chabad movement, a senior disciple of his father, Aharon HaLevi of Strashelye, a popular and respected figure, differed with him on a number of issues and led a breakaway movement.[citation needed]

Strashelye

[edit]When Schneur Zalman died, many of his followers flocked to one of his top students, Aharon HaLevi of Strashelye. He had been Shneur Zalman's closest disciple for over thirty years. While many more became followers of Dovber Shneuri, the Strashelye school of Chassidic thought was the subject of many of Dovber's discourses. Aharon HaLevi emphasized the importance of basic emotions in divine service (especially the service of prayer). Dovber Shneuri did not reject the role of emotion in prayer, but emphasized that if the emotion in prayer is to be genuine, it can only be a result of contemplation and understanding (hisbodedus) of the explanations of Chassidus, which in turn will lead to an attainment of "bittul" (self-nullification before the Divine). In his work entitled Kuntres Hispa'alus ("Tract on Ecstasy"), Dovber Shneuri argues that only through ridding oneself of what he considered disingenuous emotions could one attain the ultimate level in Chassidic worship (that is, bittul).[13]

Moshe Schneersohn

[edit]Moshe Schneersohn (born c. 1784 - died, before 1853) was the youngest son of Shneur Zalman. According to scholars he converted to Christianity and died in a St. Petersburg asylum. Chabad sources say that his conversion and related documents were faked by the Church, but Belarusian State archives in Minsk uncovered by historian Shaul Stampfer support the conversion.[14]

Lithuania

[edit]During the latter portion of Dovber's life, his students dispersed over Europe, and after Dovber's death, Shneur Zalman became the leader of Hasidism in Lithuania, along with his senior colleague Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk. When Menachem Mendel died (in 1788), Shneur Zalman was recognized as leader of the Chassidim in Lithuania.[15]

At the time Lithuania was the center of the misnagdim (opponents of Hasidism), and Shneur Zalman faced much opposition. In 1774 he and Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk traveled to Vilna in an attempt to create a dialogue with the Vilna Gaon who led the Misnagdim and had issued a ban (cherem) against the Hasidim, but the Gaon refused to see them (see Vilna Gaon: Antagonism to Hasidism and Hasidim and Mitnagdim).[citation needed]

Undaunted by this antagonism, he succeeded in creating a large network of Hasidic centers. He also joined opposition to Napoleon's advance on Russia by recruiting his disciples to the Czar's army.[16] He was also active in canvassing financial support for the Jewish settlements in the Land of Israel, then under the control of the Ottoman Empire.[citation needed]

Philosophy: Chabad

[edit] |

| Part of a series on |

| Chabad |

|---|

| Rebbes |

|

| Places and landmarks |

| Holidays |

| Organizations |

| Schools |

| Texts |

| Practices and concepts |

| Chabad offshoots |

As a Talmudist, Shneur Zalman endeavored to place Kabbalah and Hasidism on a rational basis. In his seminal work, Tanya, he defines his approach as "מוח שולט על הלב" ("mind ruling over the heart/emotions"). He chose the name "Chabad" for this philosophy—the Hebrew acronym for the intellectual attributes (sefirot) Chochma ("wisdom"), Bina ("understanding"), and Da'at ("knowledge”). According to Shneur Zalman, a man is neither a static nor a passive entity. He is a dynamic being who must work to develop his potential talent and perfect himself.[17]

Both in his works and in his sermons he "indicated an intelligent and not a blind faith",[15] and assumed an intellectual accessibility of the mystical teachings of the Kabbalah. This intellectual basis differentiates Chabad from other forms of Hasidism - in this context referred to as "Chagas"[18]—the "emotional" attributes (sefirot) of Chesed ("kindness"), Gevurah ("power"), and Tiferes ("beauty").[citation needed]

In Likkutei Sichos talks, the 7th Rebbe equates the Hasidic Rebbes followed in Chabad with different Sephirot divine manifestations: the Baal Shem Tov with Keter infinite faith, Shneur Zalman with Chokhmah (wisdom), the 2nd Chabad Rebbe with Binah (understanding), etc.[citation needed]

Opposition to Napoleon and support for the Tsar

[edit]

During the French invasion of Russia, while many Polish Hasidic leaders supported Napoleon or remained quiet about their support, Shneur Zalman openly and vigorously supported the Tsar.

While fleeing from the advancing French army he wrote a letter explaining his opposition to Napoleon to a friend, Moshe Meizeles:[19]

Should Napoleon be victorious, wealth among the Jews will be abundant . . . but the hearts of Israel will be separated and distant from their father in heaven. But if our master Alexander will triumph, though poverty will be abundant . . . the heart of Israel will be bound and joined with their father in heaven . . . . And for God's sake: Burn this letter.[20]

Some argue that Shneur Zalman's opposition stemmed from Napoleon's attempts to arouse a messianic view of himself in Jews, opening the gates of the ghettos and emancipating their residents as he conquered. He established an ersatz Sanhedrin, recruiting Jews to his ranks, and spreading rumors about his conquest of the Holy Land to make Jews subversive for his own ends.[21] Thus, his opposition was based on a practical fear of Jews turning to the false messianism of Napoleon as he saw it.[19]

Yisroel Hopsztajn of Kozienice, another Hasidic leader, also considered Napoleon a menace to the Jewish people,[22] but believed that after victory over Russia, Messiah will arrive. Menachem Mendel Schneerson identifies Hopsztajn as the Chasidic leader who preferred that Napoleon defeat the Czar.[23]

Arrests

[edit]In 1797 following the death of the Gaon, leaders of the Vilna community accused the Hasidim of subversive activities - on charges of supporting the Ottoman Empire, since Shneur Zalman advocated sending charity to support Jews living in the Ottoman territory of Palestine. In 1798 he was arrested on suspicion of treason and brought to St. Petersburg where he was held in the Petropavlovski fortress for 53 days, at which time he was subjected to an examination by a secret commission. Ultimately he was released by order of Paul I of Russia. The Hebrew day of his acquittal and release, 19 Kislev, 5559 on the Hebrew calendar, is celebrated annually by Chabad Hasidim, who hold a festive meal and make communal pledges to learn the whole of the Talmud; this practice is known as "Chalukat HaShas".

In Chabad tradition, his imprisonment is interpreted as a reflection of accusations in Heaven that he was revealing his new dimensions of mystical teachings too widely. The traditional tendency to conceal Jewish mysticism is founded on the Kabbalistic notion of the Sephirot. The side of Divine Chesed seeks to give physical and spiritual blessing without restriction. This is counterbalanced by the side of Gevurah, which measures and restricts the flow to the capacity and merit of the recipient. The subsequent Sephirah of Hod implements any restriction in order to preserve the glory of the Divine majesty. In the Hasidic story of an earlier episode among the "Holy Society" disciples of Dov Ber of Mezeritch, one of the great followers saw a page of Hasidic writings blowing around the courtyard. He regretted the undue dissemination of Hasidut for its desecration of Divine holiness. In the account, his vocalisation of these thoughts caused a Heavenly accusation against the Maggid, for revealing too much. The young Schneur Zalman replied with a famous Hasidic parable:[24]

A king had an only son who became ill and all the attending doctors were at a loss of how to heal him. A wise person understood the only possible cure. He told the king that he would have to desecrate the royal crown by removing its most precious jewel. This would have to be ground up and fed to the king's son. The king regretted the loss to his majesty but immediately agreed that the life of his son was more important. The jewel was ground and the solution was fed to the son. Most of the cure fell to the ground, but the son received a few drops and became cured. Concluded Schneur Zalman in defence of Hasidic dissemination, the king represents God, and the son represents the Jewish community, who recognise the "God of Israel". At the time of the emerging Hasidic movement, the Jewish people were at a physical and spiritual low ebb. The only cure would be the dissemination of the inner Divine teachings of Hasidic thought. Even though this would also involve their desecration, this would fully be justified in order to heal the people. The accusing student of the Maggid realised the wisdom of this, and agreed with Schneur Zalman. When the Maggid heard about this, he told Schneur Zalman that "you have saved me from the Heavenly accusation".

The story of this parable is famous across other Hasidic dynasties as well. Chabad commentary asks about this the question of why a new Heavenly accusation would have arisen against Shneur Zalman himself, and result in his incarceration in St. Petersburg. Had he not already received the Heavenly agreement to the wisdom of disseminating Chassidic teachings? Since Chabad thought presented Hasidic thought with a new degree of elucidation in intellectual form, this caused a new, more severe Heavenly accusation to emerge. This went beyond the justified spiritual revival and healing of mainstream Hasidism. Here, in Hasidic thought, Schneur Zalman was seeking to fulfill the Messianic impulse to disseminate Hasidic philosophy as a preparation for Mashiach. Therefore, his subsequent exoneration by the Tzarist authorities is interpreted in Chabad as a new Heavenly agreement to begin the fullest dissemination of Hasidic thought without its prior limitations. Chabad tradition tells that in prison, Schneur Zalman was visited by the deceased Baal Shem Tov and Maggid of Mezeritch, who told him the reason for his imprisonment. In reply to the question of whether he should stop, they replied that once released, he should continue with even more dedication. Therefore, in Chabad thought, the 19th day of Kislev is called the "New Year of Hasidut", complementing the other 4 Halachic "New Year" dates in the Hebrew calendar.

In 1800 Rav Shneur Zalman was again arrested and transported to St. Petersburg, this time along with his son Moshe who served as interpreter, as his father spoke no Russian or French. He was released after several weeks but banned from leaving St. Petersburg.[25] The accession of Tsar Alexander I (Alexander I of Russia) to the throne,a few weeks later, led to his release; he was then “given full liberty to proclaim his religious teachings” by the Russian government.

According to some, his first arrest was not the result of anti-Hasidic agitators fabricating charges, or officials seeking extortion monies.[19][26] An accusation was made on May 8, 1798 by Hirsh ben David of Vilna accused him of trying to assist the French Revolution, by sending money to Napoleon and the Sultan. Since this Hirsch ben David was untraceable, some were led to believe that there was no such person as Hirsh and the authorities were attempting to stir up internecine fighting among the Jews.[19]

Liadi

[edit]

After his release he moved his base to Liadi, Vitebsk Region, Imperial Russia; rather than returning to Liozna. He took up his residence in the town of Liadi at the invitation of Polish Prince Stanisław Lubomirski,[27] voivode of the town, were Zalman settled for the next 12 years. His movement grew there immensely, and to this day he is associated with the town. In 1812, fleeing the French Invasion, he left Mogilev, intending to go to Poltava, but died on the way in the small village of Pena, Kursk Oblast. He is buried in Hadiach.

Subsequent history of Chabad

[edit]- See Chabad#History

Dovber Schneuri moved the movement to the town of Lubavitch (Lyubavichi) in present-day Russia. A top follower of Shneur Zalman, Aharon HaLevi Horowitz, established a rival Chabad school in Strashelye, which did not last after his death.

In 1940, under the leadership of the previous Rebbe, Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, the Chabad-Lubavitch movement moved its headquarters to Brooklyn, New York in the United States. Under the leadership of Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Chabad established branches all over the world staffed by its own Lubavitch-trained and ordained rabbis with their wives and children. The number of branches continues to grow to this day, and existing branches continue to expand.

Many descendants of Shneur Zalman carry surnames such as Shneur, Shneuri, Schneerson, and Zalman.

Works

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

Shneur Zalman was a prolific writer. He produced works of both mysticism and Jewish law. Chabad tradition recasts his Yiddish name "Shneur" (שניאור) as the two Hebrew words "Shnei Ohr" (שני אור-Two Lights), referring to Schneur Zalman's mastery of both the outer dimensions of Talmudic Jewish study, and the inner dimensions of Jewish mysticism. His works form the cornerstone of Chabad philosophy. His ability to explain even the most complex issues of Torah made his writings popular with Torah scholars everywhere.

Tanya

[edit]He is probably best known for his systematic exposition of Hasidic Jewish philosophy, entitled Likkutei Amarim, more widely known as the Tanya, said to be first published in 1797.[28] The legendary 1797 Tanya got lost in a fire and no copies survived. The extant version of this work dates from 1814. Due to the popularity of this book, Hasidic Jews often refer to Shneur Zalman as the Baal HaTanya (lit. "Master of the Tanya"). The Tanya deals with Jewish spirituality and psychology from a Kabbalistic point of view, and philosophically expounds on such themes as the Oneness of God, Tzimtzum, the Sefirot, simcha, bitachon (confidence), among many other mystical concepts.

Shulchan Aruch HaRav

[edit]

Shneur Zalman is well known for the Shulchan Aruch HaRav, a collection of authoritative codes of Jewish laws and customs commissioned by Dovber of Mezeritch and composed at the legendary age of twenty-one.[29] The Maggid of Mezeritch sought a new version of the classic Shulkhan Arukh for the Hasidic movement. The work states a selection of decided halakha, as well as the underlying reasoning, and common Hasidic customs. The Shulchan Aruch HaRav is considered authoritative by other Hasidim, and citations to this work are many times found in non-Hasidic sources such as the Mishnah Berurah used by Lithuanian Jews and the Ben Ish Chai used by Sephardic Jews. Shneur Zalman is also one of three halachic authorities on whom Shlomo Ganzfried based his Kitzur Shulkhan Arukh (Concise version of Jewish law).

Siddur

[edit]He also edited the first Chabad siddur, based on the Ari Siddur of the famous kabbalist Isaac Luria of Safed, but he altered it for general use, and corrected its textual errors. Today's Siddur Tehillat HaShem is a later print of Shneur Zalman's Siddur.

Music

[edit]Shneur Zalman composed a number of Hassidic melodies. Some accompany certain prayers, others are sung to Biblical verses or are melodies without words. Depending on the tune they are meant to arouse joy, spiritual ecstasy or teshuvah. One special melody, commonly referred to as The Alter Rebbe's Niggun or Dalet Bovos, is reserved by Chabad Hassidim for ushering a groom and bride to their wedding canopy and other select occasions.

Other

[edit]Shneur Zalman's other works include:

- Torah Or and Likutei Torah, chassidic explanations of the weekly Torah portions, Shir HaShirim and the Book of Esther, drawn from his Hasidic Discourses and published by his grandson, the Tzemach Tzedek, who added his own glosses.

- Sefer HaMa'amarim, also known as Maamarei Admor HaZaken, Hassidic Discourses: Hanachot HaRaP; Et’haleich Lyozna; 5562- 2 vol.; 5563, 2 vol.; 5564; 5565, 2 vol.; 5566; 5567; 5568, 2 vol.; 5569; 5570; 5571; Haketzarim; Al Parshiyot HaTorah VehaMoadim, 2 vol.; Inyanim; Ma’amarei Razal; Nach, 3 vol.

- Hilchot Talmud Torah, on the study of Torah.

- Sefer She’elot Uteshuvot, Responsa.

- Siddur Im Dach, a prayerbook with Hasidic discourses

- Boneh Yerushalayim.

- Me'ah She'arim.

- Igrot Kodesh, 2 vol.

References

[edit]- ^ Lionel Menuhin Rolfe The Menuhins: a family odyssey - 1978 "Judah Leib and Sara had a son named Moshe, who had a son named Schneur Zalman. This first Schneur Zalman married a woman named Rachel and they had a son named Baruch. Baruch married Rebeka, a descendant of The MaHarShal."

- ^ Lubavitcher Rabbi's memoirs: The memoirs of Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn 1971 "Judah Loewe, as follows: Rabbi Judah — Betzalel — Samuel — Judah Leib — Moses of Posen — Shneur Zalman — Baruch — Shneur Zalman of Liady "

- ^ Hayom Yom, introduction

- ^ See The Maharal of Prague's Descent from King David, by Chaim Freedman, published in Avotaynu Vol 22 No 1, Spring 2006

- ^ 'Sipurie Chassidim Lenoar' Kfar Chabad 1984

- ^ The Lubavitcher Rebbe's Memoirs, vol 1.

- ^ Hayom Yom, 7 of Shvat

- ^ a b "The Alter Rebbe". www.jewishcontent.org. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- ^ "Biographical information concerning Alter Rebbe's father; yechidus; whether it is valuable to write the Tanya by hand - Letter No. 343: - Chabad.org". Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ See The Hasidic Movement and the Gaon of Vilna by Elijah Judah Schochet. For a full treatment of this subject see The Great Maggid by Jacob Immanuel Schochet, 3rd ed. 1990, ch. X, ISBN 0-8266-0414-5.

- ^ "An Encounter with the Alter Rebbe - Program One Hundred Sixty Eight - Living Torah". Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d Encyclopedia of Hasidism, entry: Schneuri, Dovber. Naftali Lowenthal. Aronson, London 1996. ISBN 1-56821-123-6

- ^ Ehrlich, Leadership in the CHaBaD Movement, pp. 160–192, esp. pp. 167–172.

- ^ Nadler, Allan (August 25, 2006). "New Book Reveals Darker Chapters In Hasidic History [Review of author David Assaf's book << "Neehaz ba-Svakh: Pirkei Mashber u-Mevucha be-Toldot ha-Hasidut" ('Caught in the Thicket: Chapters of Crisis and Discontent in the History of Hasidism') >>]". The Jewish Daily Forward. Archived from the original on October 18, 2006.

- ^ a b “Shneor Zalman Ben Baruch”. jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ^ Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, Rabbi Nissan Mindel, New York: Kehot, 1973, pp. 251–252

- ^ The World of Hassidism, H. Rabinowicz p.74, Hartmore House 1970

- ^ "Reference of Rebbe Rayatz to Chassidei "Chagas"". Chabadlibrary.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ^ a b c d Should Napoleon be victorious...": Politics and Spirituality in Early Modern Jewish Messianism, Hillel Levine, Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought 16–17, 2001

- ^ Napoleon u-Tekufato, Mevorach, pp. 182–183

- ^ Napoleon and the Jews, Kobler, F., New York, 1976.

- ^ A. Marcus, HaChasiduth, p. 114.

- ^ Igros Kodesh, Vol. 15, p. 450.

- ^ The Great Maggid by Jacob Immanuel Schochet. Kehot Publications

- ^ On learning Chassidus, Brooklyn, 1959, p. 24

- ^ Kerem Chabad, Kfar Chabad, 1992, pp. 17–21, 29–31 (Documents from the Prosecutor General's archive in St. Petersburg

- ^ Schachter-Shalomi, Zalman; Miles-Yepez, Nataniel M. (2003-03-31). Wrapped in a holy flame: teachings and tales of the Hasidic masters. Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Imprint. p. 92. ISBN 9780787965730.

- ^ Steinsaltz, Rabbi Adin (2007). Understanding the Tanya: Volume Three. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons. pp. xix. ISBN 9780787988265.

- ^ "Alter Rebbe's Shulchan Aruch – Shulchanaruchharav.com". shulchanaruchharav.com. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

External links

[edit]- Rabbi Schneur Zalman 1745–1812, chabad.org

- Founder of Chabad, chabad.org

- The Alter Rebbe Archived 2007-01-26 at the Wayback Machine, lessonsintanya.com

- Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, Adin Steinsaltz

- Rabbi Shneiur Zalman of Ladi (1746–1812) Archived 2009-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, Prof. Eliezer Segal

- Shneor Zalman Ben Baruch, jewishencyclopedia.com

- Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi 5505–5573 (1745–1812), asknoah.org

- What is Lubavitch Chasidism and Chabad? Archived 2005-11-26 at the Wayback Machine, scjfaq.org

- Family Tree

- Books by Rabbi Shneur Zalman From chabadlibrary.org

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Shneur Zalman of Liadi

- 1745 births

- 1812 deaths

- 18th-century Jewish theologians

- 18th-century philosophers

- 18th-century rabbis from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century Jewish theologians

- 19th-century philosophers

- 19th-century rabbis from the Russian Empire

- Belarusian Hasidic rabbis

- Hasidic rabbis in Europe

- Jewish philosophers

- Kabbalists

- Panentheists

- People from Lyozna District

- Philosophers of Judaism

- Philosophers of religion

- Rebbes of Lubavitch

- Russian Hasidic rabbis

- Authors of books on Jewish law

- Hasidic writers

- Students of Dov Ber of Mezeritch

- Chabad-Lubavitch poskim