Shlomo Lavi

Shlomo Lavi | |

|---|---|

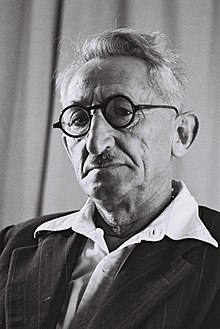

Lavi in 1951 | |

| Faction represented in the Knesset | |

| 1949–1955 | Mapai |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1882 Płońsk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 23 July 1963 |

Shlomo Lavi (Hebrew: שלמה לביא, 1882 – 23 July 1963) was a Zionist activist and politician.

Early life

[edit]Born Shlomo Levkovich in Plonsk in the Russian Empire (today in Poland), Lavi received a religious education.[1] While growing up in Plonsk, Shlomo Lavi and David Grün (the future founding father of Israel, David Ben-Gurion) were both members of the Ezra youth movement and together taught Bible lessons and Hebrew to poor and orphaned children.[2]

Zionist activity

[edit]In 1905 he made aliyah to Ottoman Palestine as part of the second Zionist wave of immigration.[1][2] In the same year he attended the founding convention of Hapoel Hatzair.[1]

Lavi worked as an agricultural laborer in Petach-Tikva, in an olive oil factory in Haifa, then at the recommendation of Arthur Ruppin as farm manager in Hulda, and together with David Ben-Gurion at Sejera.[2]

Lavi was involved in the establishment of the Jewish defence organisation Hashomer (1909-1920), which he joined as a watchman in the Galilee, in Hedera and Rehovot.[1]

Later on he joined the founders of Kvutzat Kinneret, where he worked at reclaiming marshlands.[2]

Lavi was throughout his life a dedicated member of the Zionist Labour movement and one of its ideologists.[2] Berl Katznelson, one of the founders of Labour Zionism in pre-state Israel, described Lavi as one of the "First Ten" founders of the movement.[2] He became one of the leaders and ideologists of Ahdut HaAvoda, and later co-founded Mapai.[1][2]

In 1920, he was among the founders of the Histadrut trade union.[1]

In the wake of World War I, a large influx of Jewish immigrants from the former Russian Empire was to be expected and Lavi looked for ways to prepare for their arrival, both in terms of housing and working places.[2] In this context,[2] Lavi became the originator of the idea of the larger communal settlement, the kibbutz, as opposed to the smaller kvutza preferred by earlier pioneers; in 1921 he helped establish the first such settlement, Kibbutz Ein Harod.[1] Here he lived and worked for the rest of his life.[2]

Lavi participated as a delegate in the 12th, 17th, 18th and 19th Zionist Congresses, held in 1921, 1931, 1933 and 1935, respectively.[2]

A member of the Haganah underground militia, during World War II he joined the British Army at the age of 60.[1]

Both sons of Shlomo Lavi, Yerubaal and Hillel, were killed during 1948 Arab–Israeli War, as was his brother Hillel.[2]

In 1949, Lavi was elected to the first Knesset on the Mapai party list.[1] He was re-elected in 1951, but lost his seat in the 1955 elections.[1] As a lawmaker he proposed the nationalisation of the various health and medical care programmes.[2]

A 1926 separation between two Harod Valley kibbutzim, Tel Yosef and Lavi's Ein Harod, was not to Lavi's liking, but it was nothing compared to the breakup of Kibbutz Ein Harod itself, during the sometimes violent split of the Kibbutz Movement of 1952 into the Ahdut HaAvoda/Mapai-affiliated, center-left "Ihud" branch and the Mapam's more Marxist-oriented "Meuhad" branch, which deeply affected Lavi.[2]

Late years

[edit]Shlomo Lavi spent the late years of his life in Ein Harod, finishing his last book and working in his garden.[2] He died in 1963 and was buried in Ein Harod's Old Cemetery, at the foot of Mount Gilboa, next to his wife Rachel and his two sons.[2] He was survived by his daughter, Ilana (born 1926).

A street in Kiryat Haim is named after him.

Works

[edit]- Igrot Hillel ("The Letters of Hillel")

- HaKvutzah HaGdolah ("The Large Kvutza", or group, a synonym for "kibbutz")

- Kinat Av ("Mourning of A Father")

- Megilati b'Ein Harod ("My Story in Ein Harod")

- Zimunei Haim ("Availability in Life")

- Ktavim Nivharim ("Selected Articles")

- Maarahot ("Battles")

- Alilato Shel Shlomo Laish ("The Story of Shlomo Laish")[2]

References

[edit]- 1882 births

- 1963 deaths

- British Army personnel of World War II

- People from Płońsk

- Polish emigrants to Israel

- Polish Zionists

- Jews from Ottoman Palestine

- Haganah members

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the Ottoman Empire

- Jews from the Russian Empire

- Israeli trade unionists

- Mapai politicians

- Ahdut HaAvoda politicians

- Jews from Mandatory Palestine

- Members of the 1st Knesset (1949–1951)

- Members of the 2nd Knesset (1951–1955)

- Mandatory Palestine military personnel of World War II

- Immigrants of the Second Aliyah