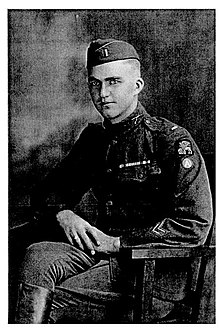

Sherwood Dixon

John Sherwood Dixon | |

|---|---|

| |

| 36th Lieutenant Governor of Illinois | |

| In office January 10, 1949 – January 12, 1953 | |

| Governor | Adlai Stevenson II |

| Preceded by | Hugh W. Cross |

| Succeeded by | John William Chapman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Sherwood Dixon June 19, 1896 Dixon, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | May 17, 1973 (aged 76) Dixon, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Helen Cahill (m. 1933) |

| Children | 5 sons, 2 daughters |

| Education | University of Notre Dame (BA) (JD) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1951 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Unit | 332nd Infantry Regiment 129th Infantry Regiment 442nd Regimental Combat Team |

| Battles/wars | World War I * Battle of Vittorio-Veneto World War II |

| Awards | Silver Star |

John Sherwood Dixon (better known as Sherwood Dixon) (June 19, 1896 – May 17, 1973) was an American politician from Illinois, a member of the Democratic Party.

Sherwood Dixon was born in Dixon, Illinois, the son of Henry S. and Margaret Casey Dixon. He was the great-grandson of the founder of Dixon, "Father" John Dixon. Dixon was a 1920 graduate of the University of Notre Dame,[1] a veteran of World War I and a brigadier general in the Illinois National Guard. Dixon was a member of the Illinois Democratic State Central Committee (1938), a delegate to the 1952 Democratic National Convention and an alternate delegate to the 1940 and 1956 Democratic national conventions.

He is best known for serving as the 36th Lieutenant Governor of Illinois, under Governor Adlai Stevenson II, from January 10, 1949, to January 13, 1953.

Lieutenant Governor Dixon and Governor Stevenson each initially sought re-election to their respective offices in in 1952, both winning renomination in their Democratic primary. However, was subsequently drafted at the Democratic National Convention Stevenson into running as the Democratic presidential nominee that year (ultimately losing the presidency to Republican nominee Dwight D. Eisenhower). Dixon replaced Stevenson as the Democratic gubernatorial nominee, but lost the election to Republican nominee William G. Stratton.

Dixon died in his hometown of the same name in 1973 and is interred in Oakwood Cemetery there.

Early life

[edit]

Sherwood Dixon was a student at Notre Dame from 1915 to 1917, as WWI was in full bloom. During his two and a half years at Notre Dame, Dixon played football and made the varsity team as a backup center to "Big Frank" Frank Rydzewski. During his playing days at Notre Dame the team finished 18-3-1 under head coach Jesse Harper and a coaching staff that included assistant coach Knute Rockne.[2] As a junior, Dixon, along with three other Notre Dame players, were caught playing semipro football for nearby Goshen, Indiana, on 4 November 1917. His violation against school rules resulted in Dixon being dismissed from the school team and suspended from the university on 10 November 1917. As his mother, Margaret (Casey) Dixon was a very strong willed and opinionated woman, Dixon enlisted as an Army private and joined the 332nd Infantry Regiment instead of returning home to face his mother's wrath.

World War I

[edit]

The 332nd was a newly formed unit in Ohio and expected soon to head off to the war. Based on his college education, Sherwood Dixon was selected to be a company clerk. By the time his unit arrived in France, he was promoted to sergeant and assigned as a squad leader in one of the companies of the 2nd Battalion, 332nd Infantry Regiment, 83rd Division of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).

In February 1918, the 332nd Infantry Regiment was sent to Italy and was the only US combat unit to fight on the Italian front during the war.[3] During the later stages of the fighting in Italy, the regiment fought in the Battle of Vittorio-Veneto. Sergeant Sherwood Dixon's squad was one of the point squads of the 2nd battalion's attack across the Tagliamento River. During the attack, Dixon's company captured the village of San Vito, the bridge (Ponte) of Delizia and the village of Codroipo. They pressed a couple of miles to the edge of the village of Villaorba where they stopped as the Armistice in Italy went into effect, marking the end of the war in Italy. For his heroism, he was awarded the Silver Star and received a battlefield commission to lieutenant.

After the Armistice of Villa Giusti, Dixon's unit moved past Trieste and on into Hungary where the 332nd became occupiers. During this period, Dixon's father, Henry S. Dixon sent him an application to take the Illinois Bar exam. Dixon completed the exam under the supervision of his company commander and returned the application which he subsequently passed. Having passed the Bar exam, Dixon return from the war as a decorated veteran, an Officer and as a lawyer after having fled college following his expulsion.

Interwar years

[edit]Upon returning to the United States and the University of Notre Dame, Dixon complete his undergraduate work in 1919 and Law School in 1920. By this point, Knute Rockne had succeeded Jesse Harper as Notre Dame's Head Coach and while back at school Dixon aided his former coach but did not return to playing football. After completing his formal education, Dixon returned to his hometown where he joined the family law practice. Over the coming years Dixon remained active with the Illinois National Guard and was an early leader of the local American Legion. Back in his hometown, Dixon would meet Helen Cahill, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William Cahill. Helen was a school teacher in Dixon. Once again defying his strong willed mother, in September 1933 he and Helen eloped, drove to his alma mater and were wed at the log chapel on the campus at Notre Dame.[4] Their first child, Henry Sherwood Dixon, would be born the following year. In the 1930s, Dixon would begin his foray into politics as a Democrat. Dixon served as president of the local school board and later served on various Democratic central committees to include both Lee County, and at the State level for Illinois.

World War II

[edit]In early 1941, now Lieutenant Colonel Sherwood Dixon commanded in the 129th Infantry Regiment as part of the 33rd Infantry Division of the Illinois National Guard when it was called to active duty. Within two years the 129th would be sent to the Pacific Theater of Operations, but because Dixon was over 45 years old, it was against Army regulations for him to deploy overseas. Instead, he was sent to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and on 1 February 1943 Lieutenant Colonel Sherwood Dixon became the commander of the newly activate 3rd Battalion of the 442nd Infantry Regiment. The 442nd was a “Nisei” unit composed of Japanese Americans, mostly from the Hawaiian Islands, but the officers above the rank of Lieutenant were white officers.[5] Training started at the individual level but by the fall of 1943 the regiment had moved to company and battalion level training and exercises. Dixon focused on ensuring the battalion was at a top level of fitness and able to fight, even after extensive foot marches similar to what he experienced during the First World War. Early in 1944, the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George C. Marshall, came to Mississippi to observe the regiment during maneuvers. Marshall was impressed with the performance of the unit. Shortly after, in late February 1944, the Army declared the 442nd combat ready. The unit soon began preparation for deployment to the European Theater of Operations. The 442nd Regiment became the most decorated unit in the history of American warfare, earning over 4,000[6] Purple Hearts, eight Presidential Unit Citations (five in one month), and twenty-one of its members were awarded Medals of Honor. Again, Sherwood Dixon would be unable to deploy with the unit he trained, nurtured and mentored for the past year due to his age. Instead of heading off to fight in Italy for the second time, he was assigned to work for General Marshall in the Office of the Chief of Staff, in Washington DC. Dixon moved the now growing family of seven from southwest Mississippi to Alexandria, Virginia where he worked for the remainder of the war. However, his year with the 442nd created bonds with Japanese Americans that remained throughout the remainder of his life. Dixon would maintain correspondence with his former Soldiers as they fought in Italy, Southern France and into Germany. After the war he would frequently travel to Hawaii with his wife, Helen, to spend time with his former Soldiers and as late as 1997 his photo still hung in the 442nd Club in downtown Honolulu.

Political life

[edit]The November 2, 1948 Democratic ticket of Adlai E. Stevenson for Governor and Sherwood Dixon as Lieutenant Governor defeated the Republican nominees of Dwight Green and Richard Yates Rowe. Stevenson and Dixon mimicked the "whistle stop" tactic employed that year by the Democratic presidential nominee Harry S. Truman. Their campaigning saw as many as 10 speeches a day.

As the Illinois Lieutenant Governor, Sherwood Dixon presided over the Illinois State Senate as president pro tempore. During his tenure the legislative body consisted of only 18 Democrats to 32 Republicans. During the later part of his term, Dixon spent considerable time as acting governor for Stevenson, who was spending most of his time outside of Illinois during his campaign as the 1952 Democratic presidential nominee. During this time, Sherwood Dixon was running his own campaign to succeed Stevenson as Governor. With only a week before the election, both Stevenson and Dixon would postpone their campaigns temporarily to respond to the prison riot at the Illinois State Prison at Menard. During the riot, over 300 prisoners seized control of one of the cell blocks for four days, while taking seven prison guards hostage.[7] During the riot, Dixon's wife, Helen, substituting for her husband, appeared at numerous campaign events to include being at the side of President Harry S. Truman at one of his "whistle stops" in Illinois. Dixon ended up losing to Stratton by 227,642 votes, 5.16%.[8]

Personal life

[edit]Sherwood Dixon's wife, Helen Cahill, was the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William Cahill, also of Dixon, Illinois. Sherwood and Helen married at the chapel on the campus of the University of Notre Dame in September, 1933. They had seven children Henry, Mary, William, Louise, James, Patrick, and David. Their son, James E. Dixon, was Mayor of Dixon from 1983 to 1991. Their son, 1LT Patrick M. Dixon, was killed in action in Vietnam on 28 May 1969.[9]

References

[edit]Specific

- ^ "Chicago Tribune: Chicago news, sports, weather, entertainment".

- ^ "2016 Media Guide Notre Dame Football" (PDF). University of Notre Dame Fighting Irish Media. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Dalessandro, Robert J. & Rebecca S. (2010). American Lions, The 332nd Infantry Regiment in Italy in World War One. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing.

- ^ Langan, Greg (2002). "When Dixon had a lieutenant governor". Dixon Evening Telegraph.

- ^ Shirey, Orville (1946). Americans: The Story of The 442d Combat Team. Washington Infantry Journal Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1258423360.

- ^ 442nd Regimental Combat Team

- ^ "Week-Long Prison Riot Is Broken, Madera Tribune — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. October 31, 1952. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ "1952 Gubernatorial General Election Results - Illinois". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Dame, Marketing Communications: Web // University of Notre. "1LT Patrick Dixon, Class of 1967 // Army ROTC // University of Notre Dame". Army ROTC. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- Illinois Democrats

- School board members in Illinois

- Lieutenant governors of Illinois

- 1896 births

- 1973 deaths

- People from Dixon, Illinois

- Notre Dame Law School alumni

- Illinois lawyers

- Military personnel from Illinois

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- 20th-century American politicians

- 20th-century American lawyers