Sheldon Peck

Sheldon Peck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 26, 1797 Cornwall, Vermont, United States |

| Died | March 19, 1868 (aged 70) Babcock's Grove (present-day Lombard, Illinois), United States |

| Occupation(s) | Artist Farmer Social activist |

| Movement | Abolitionism Underground Railroad Racial equality Temperance movement Public education Women's rights Pacifism |

| Spouse | Harriet Cory (m.1825–1869; his death) |

| Children | John Peck Charles Peck George Peck Abigal Peck Alanson Peck Watson Peck Martha Peck Henry Peck Susan Elizabeth Peck Abigal Corey Peck Sanford Peck Frank Hale Peck (Unnamed infant) |

| Parent(s) | Jacob Peck Elizabeth Gibbs |

Sheldon Peck (August 26, 1797 - March 19, 1868) was an American folk artist, conductor on the Underground Railroad, and social activist. Peck's portraiture – with its distinctive style — is a prime example of 19th century American folk art. He also become known for advocating abolitionism, racial equality, temperance, public education, women's rights, and pacifism.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Peck was born in Cornwall, Vermont, the ninth son of Jacob and Elizabeth Peck. Peck's ancestors helped found the New Haven Colony; his father worked as a blacksmith and served as a private in the Revolutionary War.[2]

Peck married Harriet Corey (1806-1887) in 1825 and the couple eventually had thirteen children. The Peck family moved to Jordan, New York in 1828 and lived there until moving westward to Chicago in 1836. A year later Peck finally settled in Babcock's Grove (now Lombard) approximately twenty-five miles west of Chicago. On his 160 acres of farmland, Peck built a 1+1⁄2-story timber-frame house (completed in 1839) that still stands today. He grew crops and raised Merino sheep, the latter being a way to produce raw material for clothes without supporting the Southern-based cotton industry and its use of African slave labor. No records exist to indicate that Peck received any formal art education. His work may have been influenced by William Jennys, a primitive portrait painter who was active in Vermont around the time Peck lived there. Peck also would have had access to art instruction texts that were housed in the library of the Cornwall Young Gentleman's Society.[2]

Artwork

[edit]Peck primarily painted portraits (although he also dabbled in decorative furniture painting). Peck's portraiture can be divided into three distinctive periods, based on where he lived at the time.

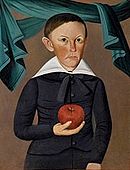

Vermont Period, ca. 1820 - 1828

[edit]Peck's earliest works date to around 1820 and consist primarily of waist-length oil portraits on wood panels; many of his earliest pieces depicted members of his own family. Early on Peck established his characteristic simple approach to portraiture. During this period the figures in Peck's paintings have somber faces with hard, angular planes, and immobile expressions. The figures are painted against dark, undercoated backgrounds. By keeping the portraits to the waist, Peck avoided the challenges of painting full-figures.[2]

Peck's signature decorative motif – the rabbit track – is already well established in this period. The three brushstrokes (one long stoke flanked by two shorter ones) resembles the footprint of a rabbit and reappears often in Peck's portraits, usually found in clothing or somewhere in the background. While this three brushstroke motif was popular during the period – particularly among ornamental painters working on furniture or tinware – it is so closely associated with Peck that it has become his de facto signature as he did not sign his paintings (a common practice at the time).[3]

New York Period, 1828 - 1836

[edit]Upon his arrival in New York in 1828, Peck continued to paint half-length portraits on wood panels as he had in Vermont. He did, however, begin to use a somewhat brighter color palette and began embellishing his subjects with personal accessories such as jewelry, Bibles, fruit, decorated furniture, and swags of drapery in the background. These were popular portrait conventions during the period and suggest that Peck was influenced by – or at the very least, observed – the work of other artists.[2]

Illinois Period, 1836 - 1869

[edit]

In 1836 Peck moved to Chicago where he lived for only a few months before moving once again and settling in Babcock's Grove. Once in Illinois, Peck abandoned wood panels in favor of canvas. During his first years in the state, Peck continued to paint half-length portraits similar to those he had painted back East.

It is in Illinois, however, that the most radical shift in Peck's work occurs. About 1845 daguerreotypes were gaining in popularity in the United States. To compete against photography and the advantages it offered, Peck introduced a brighter color palette to his work. He also employed a horizontal format, which featured multiple full length figures, their arrangement taking cues from photography. (see image at right) Additionally, Peck would add a trompe-l'œil frame painted directly onto the canvas. This was likely done to reduce the overall cost of the painting by sparing the customer the expense of having the canvas framed.[2]

Activism

[edit]From 1828 to 1836, Peck lived in an area of New York known as the burned-over district, a hot bed of various reform movements in the 19th century, including abolitionism, temperance, women's rights, and public education. Peck adopted many of these beliefs and advocated for social change throughout his lifetime.

Abolitionism

[edit]Peck was considered a "radical abolitionist" who advocated for the immediate end of slavery as well as equal rights for African-Americans. While living in Illinois he was a volunteer agent for the abolitionist newspaper the Western Citizen, meaning he would collect dues on behalf of the newspaper as well as disseminate the Citizen's anti-slavery views.[4] In addition to working for the Western Citizen, Peck was a delegate for the Liberty Party – a political party whose main focus was the abolition of slavery.[5] Peck was also a member of the DuPage County Anti-Slavery Society (part of the Illinois State Anti-Slavery Society).[6] In 1856, Peck served as a DuPage County delegate to the Illinois State Abolitionism Convention, which a New York Times article at the time dubbed a "Convention of Radical Abolitionists," meaning that the ideas expressed went beyond ending slavery but encompassed racial equality as well.[7] In addition to working with abolitionist parties, Peck would often invite guest speakers to his home to lecture about the evils of slavery.[8] Two prominent African-American speakers who came to the Peck house were Johnny Jones (a free-born mulatto who was active in the Chicago anti-slavery movement and was an associate of John Brown) and H. Ford Douglass (an escaped slave who was a celebrated orator and friend of Frederick Douglass).[9]

Underground Railroad

[edit]Numerous accounts exist to confirm that Peck actively worked as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. It is generally believed that Peck would hide freedom seekers on his property and then move them via wagon to Chicago. This would enable the freedom seekers to travel to Canada via rail or the Great Lakes. Another possible route was along the Fox Valley (many of whose residents hired Peck to paint their portraits) northward on foot or canoe along the Fox River to Wisconsin and thence Canada. (Escaping to Canada was necessary after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 became law, because escaped slaves could still be returned to bondage even if they reached free states in the North.) Peck traveled frequently throughout north eastern Illinois to paint his subjects and this travel provided a cover for his Underground Railroad work.[1] His youngest son, Frank Peck, recorded details about his father's work in journals and often shared how his family's home was part of the Underground Railroad:

Back in my boy hood days, my father, who was an abolitionist, helped the Negroes escape from slavery in the South. Our home was used as a headquarters for all opponents of slavery in this part of the country, a station for the underground railway. I can remember one incident as clearly as if it was yesterday – when my father protected seven Negroes one night, when I was a small boy, helping them on their way to the Chicago district.[10]

Frank Peck also recounts the slave spirituals that he sang with the freedom seekers at his family's home, in particular the songs sung by an Underground Railroad conductor (and escaped slave) known as "Old Charley":

Roll on tibler moon, guide the tabler not astray

Whilest the nightingale song is in full tune

While I sadly complain to the moon.[11]

(Sung in slave dialect, "tibler moon" is thought to be the "traveling moon" – a full, bright moon whose light would aid escapees during their journey.) Frank Peck's daughter also recalled how freedom seekers were, "hid in barns around the [Peck] homestead, then carried away the next day in a load of hay on their way to the Canadian border and freedom."[12]

Temperance

[edit]The anti-slavery and temperance movements were closely linked in the 19th century, and Peck advocated for both causes. Peck held temperance meetings on his property, and they were often advertised in the abolitionist Western Citizen newspaper.[13] Additionally, the Peck family would host "temperance picnics at the Grove," an opportunity for Chicagoans to enjoy a day-long, liquor-free excursion to Peck's farm in Babcock's Grove.[14] Like many people at the time, Peck believed that liquor led to a variety of social and health problems. His youngest son, Frank Peck, recounted how prevalent the idea of temperance was while growing up:

The temperance movement was much discussed...I am sorry to say that many of my friends and acquaintances have filled untimely graves from the effect of strong drink with deliriums and often troubles caused from it and I have helped care for some of them and have only one conclusion, it is a good thing to shun entirely.[9]

Public Education

[edit]Prior to the 1820s, free public education was not considered a responsibility of government. The reform movements of the 19th century, however, changed that view, and Peck in particular supported free public education as a means to protect democracy against ignorance.

Upon his arrival in Babcock's Grove in 1836, Peck established a school in his house. He personally paid the salary for the school's teacher, Amelda Powers Dodge, and invited all the children in the area to attend classes. He later erected another building on his property for use as a school and public meeting space. Peck later served as superintendent of a Sunday school organized by the local Methodist church.[15]

Death and legacy

[edit]Peck died on March 19, 1869, survived by his wife and ten of his thirteen children. He is buried in the Lombard Cemetery. His youngest son, Frank, kept a diary which historians find very useful in documenting negro spirituals as well as the Underground Railroad.

Sheldon Peck Homestead

[edit]Sheldon Peck's 1839 house was donated to the Lombard Historical Society by his granddaughter. It is now operated as the Sheldon Peck Homestead, a museum dedicated to Peck's work as an activist and artist.[16] The house is listed on the register of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom as a confirmed Underground Railroad site.

Value of his work

[edit]The value of Peck's art has risen considerably over the years, mirroring the rise in status of folk and primitive art. His paintings can be seen at museums around the United States including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Chicago History Museum, and the American Folk Art Museum in New York City. Because Peck never signed his work, "new" Peck portraits are constantly being discovered.

-

William W. Welch

-

Phebe Welch

-

Mr. S. Vaughn. Note the trompe-l'œil painted frame.

-

Unknown Gentleman with Red Drape. Hidden behind a $25 lithograph, this portrait sold for $79,000 at auction.

-

Young Girl in Blue Dress Holding an Egg

-

George Weld Hilliard

-

David and Catherine Stolp Crane

-

Anna Gould Crane and Granddaughter Janette

-

Mr. and Mrs. William Vaughan

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Turner, Glennette Tilley. The Underground Railroad in Illinois, 2001.

- ^ a b c d e Lipman, Jean and Armstrong, Tom. American Folk Painters of the Three Centuries, 1980.

- ^ In addition, ongoing research attempts to link Peck's trademark "rabbit track" as a symbol of the anti-slavery movement, as the one known pro-slavery (or at least apathetic) subject among his paintings does not have the rabbit tracks. However, this remains speculation until further research is done.

- ^ Western Citizen, Chicago, "Receipts for the Citizen, from Jan. 11 to Jan. 18," January 18, 1848.

- ^ Western Citizen, Chicago, "State Convention of the Liberty Party of Illinois" Feb. 1, 1844, Western Citizen, Chicago, "A Call for a North-Western Liberty Convention at Chicago" May 6, 1846.

- ^ Western Citizen, Chicago, "Liberty Mass Meeting" Jan. 18, 1848

- ^ New York Times, "Illinois State Abolition Convention – An Electoral Ticket Nominated," Aug. 11, 1856.

- ^ Chicago Press and Tribune, "Anti-Slavery Meetings" Oct. 3, 1859.

- ^ a b Peck, Frank, journal, copy at the Lombard Historical Society, Lombard, IL, p. 4-5.

- ^ Lombard Spectator, Lombard, Illinois, "Lombard's Oldest Born Citizen Busy on 'Reminiscences,'" September 3, 1931.

- ^ Peck, Frank, journal, copy at the Lombard Historical Society, Lombard, IL, p. 2-3.

- ^ Lombard Spectator, 1950.

- ^ Western Citizen, "Temperance Meeting," Oct. 24, 1848.

- ^ Western Citizen, "Temperance Meeting at Babcock's Grove," March 16, 1852.

- ^ Vandercook, Dorothy I. and Kaiser, Blythe. Glen Ellyn's Story and Her Neighbors in DuPage, 1976.

- ^ "Freedom of Information Act | Lombard, IL". Villageoflombard.org. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Bateman, Newton and Selby, Paul. Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois and History of Du Page County, 1913.

- Budd, Lillian. Footsteps on the Tall Grass Prairie: A History of Lombard Illinois, 1976.

- Still, William. The Underground Railroad: Authentic Narratives and First-Hand Accounts, 2007.

External links

[edit]- Sheldon Peck Homestead Archived 2013-12-13 at the Wayback Machine - Lombard Historical Society

- National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom

- American Folk Art Museum - Four Peck portraits are view-able online

- Sheldon Peck: Portrait of an Ordinary Man in Extraordinary Times - 2018 Documentary on the life of Sheldon Peck