Amber Fort

| Amer fort | |

|---|---|

| Part of Rajasthan | |

| Amer, Rajasthan, India | |

| |

| Coordinates | 26°59′09″N 75°51′03″E / 26.9859°N 75.8507°E |

| Type | Fort and Palace |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Government of Rajasthan |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Good |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1592[1] |

| Built by | Man Singh I |

| Materials | Sandstone and marble |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii |

| Designated | 2013 (37th session) |

| Part of | Hill Forts of Rajasthan |

| Reference no. | 247 |

| Region | South Asia |

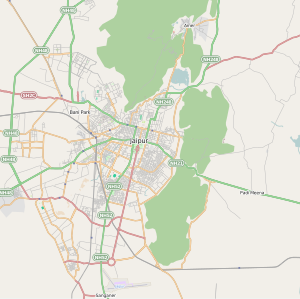

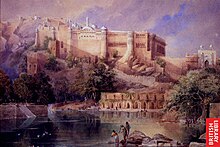

Amer Fort or Amber Fort is a fort located in Amer, Rajasthan, India. Amer is a town with an area of 4 square kilometres (1.5 sq mi)[2] located 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from Jaipur, the capital of Rajasthan. Located high on a hill, it is the principal tourist attraction in Jaipur.[3][4] Amer Fort is known for its artistic style elements. With its large ramparts and series of gates and cobbled paths, the fort overlooks Maota Lake,[4][5][6][7] which is the main source of water for the Amer Palace.

Amer Palace is great example of Rajput architecture. Some of its buildings and work have influence of Mughal architecture.[8][9][10] Constructed of red sandstone and marble, the attractive, opulent palace is laid out on four levels, each with a courtyard. It consists of the Diwan-e-Aam, or "Hall of Public Audience", the Diwan-e-Khas, or "Hall of Private Audience", the Sheesh Mahal (mirror palace), or Jai Mandir, and the Sukh Niwas where a cool climate is artificially created by winds that blow over a water cascade within the palace. Hence, the Amer Fort is also popularly known as the Amer Palace.[5] The palace was the residence of the Rajput Maharajas and their families. At the entrance to the palace near the fort's Ganesh Gate, there is a temple dedicated to Shila Devi, a Goddess of the Chaitanya cult, which was given to Raja Man Singh when he defeated the Raja of Jessore, Bengal in 1604. (Jessore is now in Bangladesh).[4][11][12] Raja Man Singh had 12 queens so he made 12 rooms, one for each Queen. Each room had a staircase connected to the King’s room but the Queens were not to go upstairs. Raja Jai Singh had only one queen so he built one room equal to three old queen’s rooms.

This palace, along with Jaigarh Fort, is located immediately above on the Cheel ka Teela (Hill of Eagles) of the same Aravalli range of hills. The palace and Jaigarh Fort are considered one complex, as the two are connected by a subterranean passage. This passage was meant as an escape route in times of war to enable the royal family members and others in the Amer Fort[13] to shift to the more redoubtable Jaigarh Fort.[5][14][15] Annual tourist visitation to the Amer Palace was reported by the Superintendent of the Department of Archaeology and Museums as 5000 visitors a day, with 1.4 million visitors during 2007.[2] At the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in 2013, Amer Fort, along with five other forts of Rajasthan, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the group Hill Forts of Rajasthan.[16]

Etymology

Amer, or Amber, derives its name from the Ambikeshwar Temple, built atop the Cheel ka Teela. Ambikashwara is a local name for the god Shiva. However, local folklore suggests that the fort derives its name from Amba, the Mother Goddess Durga.[17]

Geography

Amer Palace is situated on a forested hill promontory that juts into Maota Lake near the town of Amer, about 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from Jaipur city, the capital of Rajasthan. The palace is near National Highway 11C to Delhi.[18] A narrow 4WD road leads up to the entrance gate, known as the Suraj Pol (Sun Gate) of the fort. It is now considered much more ethical for tourists to take jeep rides up to the fort, instead of riding the elephants.

History

Early history

Amber was a Meena state, ruled by a Susawat clan. After Kakil Deo defeated the Susawats he made Amber the capital of Dhundhar after Khoh. Kakil Deo was a son of Dulherai.[19][20]

In early times, the state of Jaipur was known as Amber or Dhundhar and was controlled by Meena chiefs of five different tribes. They were under suzerainty of the Bargurjar Rajput Raja of Deoti. Later a Kachhwaha prince, Dulha Rai, destroyed the sovereignty of Meenas and also defeated Bargurjars of Deoli and took Dhundhar fully under Kachwaha rule.[21]

The Amber Fort was originally built by Raja Man Singh. Jai Singh I expanded it in the early 1600's. Improvements and additions were made by successive rulers over the next 150 years, until the Kachwahas shifted their capital to Jaipur during the time of Sawai Jai Singh II, in 1727.[2][22]

In the medieval period, Amer was known as Dhundar (meaning attributed to a sacrificial mount in the western frontiers) and ruled by the Kachwahas from the 11th century onwards – between 1037 and 1727 AD, until the capital was moved from Amer to Jaipur.[5] The history of Amer is indelibly linked to these rulers as they founded their empire at Amer.[23]

Layout

The Palace is divided into six separate but main sections each with its own entry gate and courtyard. The main entry is through the Suraj Pol (Sun Gate) which leads to the first main courtyard. This was the place where armies would hold victory parades with their war bounty on their return from battles, which were also witnessed by the Royal family's womenfolk through the latticed windows.[24] This gate was built exclusively[clarification needed] and was provided with guards as it was the main entry into the palace. It faced east towards the rising sun, hence the name. Royal cavalcades and dignitaries entered the palace through this gate.[25]

Jaleb Chowk is an Arabic phrase meaning a place for soldiers to assemble. This is one of the four courtyards of Amer Palace, which was built during Sawai Jai Singh's reign (1693–1743 AD). Maharaja's personal bodyguards held parades here under the command of the army commander or Fauj Bakshi. The Maharaja used to inspect the guards contingent. Adjacent to the courtyard were the horse stables, with the upper-level rooms occupied by the guards.[26]

First courtyard

An impressive stairway from Jalebi Chowk leads into the main palace grounds. Here, at the entrance to the right of the stairway steps is the Sila Devi temple where the Rajput Maharajas worshipped, starting with Maharaja Mansingh in the 16th century until the 1980s, when the animal sacrifice ritual (sacrifice of a buffalo) practiced by the royalty was stopped.[24]

Ganesh Pol, or the Ganesh Gate, named after the Hindu deity Ganesha, believed to remove all obstacles in life, is the entry into the private palaces of the Maharajas. It is a three-level structure with many frescoes that were also built at the orders of the Mirza Raja Jai Singh (1621–1627). Above this gate is the Suhag Mandir where ladies of the royal family used to watch functions held in the Diwan-i-Aam through latticed marble windows called "jâlîs".[27]

- Sila Devi temple

On the right side of the Jalebi Chowk, there is a small but an elegant temple called the Sila Devi temple (Sila Devi was an incarnation of Kali or Durga). The entrance to the temple is through a double door covered in silver with a raised relief. The main deity inside the sanctum is flanked by two lions made of silver. The legend attributed to the installation of this deity is that Maharaja Man Singh sought blessings from Kali for victory in the battle against the Raja of Jessore in Bengal. The goddess instructed the Raja, in a dream, to retrieve her image from the sea bed and install and worship it. The Raja, after he won the battle of Bengal in 1604, retrieved the idol from the sea and installed it in the temple and called it Sila Devi as it was carved out of one single stone slab. At the entrance to the temple, there is also a carving of Ganesha, which is made out of a single piece of coral.[24]

Another version of the Sila Devi installation is that Raja Man Singh, after defeating the Raja of Jessore, received a gift of a black stone slab which was said to have a link to the Mahabharata epic in which Kamsa had killed older siblings of Krishna on this stone. In exchange for this gift, Man Singh returned the kingdom he had won to the Raja of Bengal. This stone was then used to carve the image of Durga Mahishasuramardini, who had slain the asura king Mahishasura and installed it in the fort's temple as Sila Devi. The Sila Devi was worshiped from then onwards as the lineage deity of the Rajput family of Jaipur. However, their family deity continued to be Jamva Mata of Ramgarh.[12]

Another practice that is associated with this temple is the religious rites of animal sacrifice during the festival days of Navaratri (a nine-day festival celebrated twice a year). The practice was to sacrifice a buffalo and also goats on the eighth day of the festival in front of the temple, which would be done in the presence of the royal family, watched by a large gathering of devotees. This practice was banned under the law from 1975, after which the sacrifice was held within the palace grounds in Jaipur, strictly as a private event with only the close kin of the royal family watching the event. However, now the practice of animal sacrifice has been totally stopped at the temple premises and offerings made to the goddess are only of the vegetarian type.[12]

Second courtyard

The second courtyard, up the main stairway of the first level courtyard, houses the Diwan-i-Aam or the Public Audience Hall. Built with a double row of columns, the Diwan-i-Aam is a raised platform with 27 colonnades, each of which is mounted with an elephant-shaped capital, with galleries above it. As the name suggests, the Raja (King) held audience here to hear and receive petitions from the public.[5][24]

Third courtyard

The third courtyard is where the private quarters of the Maharaja, his family and attendants were located. This courtyard is entered through the Ganesh Pol or Ganesh Gate, which is embellished with mosaics and sculptures. The courtyard has two buildings, one opposite to the other, separated by a garden laid in the fashion of the Mughal Gardens. The building to the left of the entrance gate is called the Jai Mandir, which is exquisitely embellished with glass inlaid panels and multi-mirrored ceilings. The mirrors are of convex shape and designed with colored foil and paint which would glitter bright under candlelight at the time it was in use. Also known as Sheesh Mahal (mirror palace), the mirror mosaics and colored glasses were a "glittering jewel box in flickering candlelight".[5] Sheesh mahal was built by King Man Singh in the 16th century and completed in 1727. It is also the foundation year of Jaipur state.[28] However, most of this work was allowed to deteriorate during the period 1970–80 but has since then been in the process of restoration and renovation. The walls around the hall hold carved marble relief panels. The hall provides enchanting vistas of the Maota Lake.[24]

On top of Jai Mandir is Jas Mandir, a hall of private audience with floral glass inlays and alabaster relief work.[5]

The other building seen in the courtyard is opposite to the Jai Mandir and is known as the Sukh Niwas or Sukh Mahal (Hall of Pleasure). This hall is approached through a sandalwood door. The walls are decorated with marble inlay work with niches called "chînî khâna". A piped water supply flows through an open channel that runs through this edifice keeping the environs cool, as in an air-conditioned environment. The water from this channel flows into the garden.

- Magic flower

A particular attraction here is the "magic flower" carved marble panel at the base of one of the pillars around the mirror palace depicting two hovering butterflies; the flower has seven unique designs including a fishtail, lotus, hooded cobra, elephant trunk, lion's tail, cob of corn, and scorpion, each one of which is visible by a special way of partially hiding the panel with the hands.[5]

- Garden

The garden, located between the Jai Mandir on the east and the Sukh Niwas on the west, both built on high platforms in the third courtyard, was built by Mirza Raja Jai Singh (1623–68). It is patterned on the lines of the Chahar Bagh or Mughal Garden. It is in a sunken bed, shaped in a hexagonal design. It is laid out with narrow channels lined with marble around a star-shaped pool with a fountain at the center. Water for the garden flows in cascades through channels from the Sukh Niwas and also from the cascade channels called the "chini khana niches" that originate on the terrace of the Jai Mandir.[15]

- Tripolia gate

Tripolia gate means three gates. It is access to the palace from the west. It opens in three directions, one to the Jaleb Chowk, another to the Man Singh Palace and the third one to the Zenana Deorhi on the south.

- Lion gate

The Lion Gate, the premier gate, was once a guarded gate; it leads to the private quarters in the palace premises and is titled 'Lion Gate' to suggest strength. Built during the reign of Sawai Jai Singh (1699–1743 AD), it is covered with frescoes; its alignment is zigzag, probably made so from security considerations to attack intruders.

Fourth courtyard

The fourth courtyard is where the Zenana (Royal family women, including concubines or mistresses) lived. This courtyard has many living rooms where the queens resided and who were visited by the king at his choice without being found out as to which queen he was visiting, as all the rooms open into a common corridor.[24]

- Palace of Man Singh I

South of this courtyard lies the Palace of Man Singh I, which is the oldest part of the palace fort.[5] The palace took 25 years to build and was completed in 1599 during the reign of Raja Man Singh I (1589–1614). It is the main palace. In the central courtyard of the palace is the pillared baradari or pavilion; frescoes and colored tiles decorate the rooms on the ground and upper floors. This pavilion (which used to be curtained for privacy) was used as the meeting venue by the maharanis (queens of the royal family). All sides of this pavilion are connected to several small rooms with open balconies. The exit from this palace leads to the town of Amer, a heritage town with many temples, palatial houses and mosques.[4]

The queen mothers and the Raja's consorts lived in this part of the palace in Zanani Deorhi, which also housed their female attendants. The queen mothers took a deep interest in building temples in Amer town.[29]

Conservation

Six forts of Rajasthan, namely, Amber Fort, Chittor Fort, Gagron Fort, Jaisalmer Fort, Kumbhalgarh and Ranthambore Fort were included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site list during the 37th meeting of the World Heritage Committee in Phnom Penh during June 2013. They were recognized as a serial cultural property and examples of Rajput military hill architecture.[30][31]

The town of Amer, which is an integral and inevitable entry point to Amer Palace, is now a heritage town with its economy dependent on the large influx of tourists (4,000 to 5,000 a day during peak tourist season). This town is spread over an area of 4 square kilometres (1.5 sq mi) and has eighteen temples, three Jain mandirs, and three mosques. It has been listed by the World Monument Fund (WMF) as one of the 100 endangered sites in the world; funds for conservation are provided by the Robert Wilson Challenge Grant.[2] As of 2005, some 87 elephants lived within the fort grounds, but several were said to be suffering from malnutrition.[32]

Conservation works have been undertaken at the Amer Palace grounds at a cost of Rs 40 crores (US$8.88 million) by the Amer Development and Management Authority (ADMA). However, these renovation works have been a subject of intense debate and criticism with respect to their suitability to maintain and retain the historicity and architectural features of the ancient structures. Another issue which has been raised is the commercialization of the place.[33]

A film unit shooting a film at the Amer Fort damaged a 500-year-old canopy, demolished the old limestone roof of Chand Mahal, drilled holes to fix sets and spread large quantities of sand in Jaleb Chowk in utter disregard and violation of the Rajasthan Monuments, Archaeological Sites and Antique Act (1961).[34] The Jaipur Bench of the Rajasthan High Court intervened and stopped the film shooting with the observation that "unfortunately, not only the public but especially the concerned (sic) authorities have become blind, deaf and dumb by the glitter of money. Such historical protected monuments have become a source of income."[34]

Concerns of elephant abuse

Several groups have raised concerns regarding the abuse of elephants and their trafficking and have highlighted what some consider the inhumane practice of riding elephants up to the Amber Palace complex.[35] The organization PETA as well as the central zoo authority have taken up this serious issue. The Haathi gaon (Elephant village) is said to be in violation of captive animal controls, and a PETA team found elephants chained with painful spikes, blind, sick and injured elephants forced to work, and elephants with mutilated tusks and ears.[36] In 2017, A New York-based tour operator announced it would use Jeeps instead of elephants for the trip to Amber Fort, saying "It’s not worth endorsing … some really significant mistreatment of animals."[37]

In Art and Literature

An engraving of a painting of the fort by W. Purser, under the title Shuhur, Jeypore, was published in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1834, with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon.[38]

Gallery

-

Bright morning vista of Amer Fort from across the road.

-

Amer Fort lit up at night.

-

Maota Lake and Kesar Kyari (Saffron Garden).

-

Outer wall

-

A fusion of Rajputana Hindu and Mughal Islamic style of architecture

-

Sattais Kacheri

-

Second Courtyard Mirror Palace Amer Fort.

-

Sheesh Mahal Arch

-

Embossed silver artwork in Sheesh Mahal

-

Windows

-

Tunnels inside the fort

-

An outer door

See also

References

- ^ "Outlook". Outlook. December 2008.

- ^ a b c d Outlook Publishing (2008). Outlook. Outlook Publishing. p. 39.

- ^ Mancini, Marc (2009). Selling Destinations: Geography for the Travel Professional. Cengage Learning. p. 539. ISBN 978-1-4283-2142-7.

- ^ a b c d Abram, David (2003). Rough guide to India. Rough Guides. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-84353-089-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pippa de Bruyn; Keith Bain; David Allardice; Shonar Joshi (2010). Frommer's India. Frommer's. pp. 521–522. ISBN 978-0-470-55610-8.

- ^ "Amer Fort - Jaipur". Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ "Maota Sarover -Amer-jaipur". Agam pareek. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Amer | India". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ DK (2 November 2009). Great Monuments of India. Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 9781405347822.

- ^ Bhargava, Visheshwar Sarup (1979). Rise of the Kachhawas in Dhundhār (Jaipur): From the Earliest Times to the Death of Sawai Jai Singh (1743 A.D.). Shabd Sanchar.

- ^ Rajiva Nain Prasad (1966). Raja Mān Singh of Amer. World Press. ISBN 9780842614733.

- ^ a b c Lawrence A. Babb (2004). Alchemies of violence: myths of identity and the life of trade in western India. SAGE. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-0-7619-3223-9.

- ^ "Glorious Amber Fort Breath Taking Place To Visit In Jaipur 2020". Fort Trek. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Jaipur". Jaipur.org.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ a b D. Fairchild Ruggles (2008). Islamic gardens and landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 978-0-8122-4025-2.

- ^ Singh, Mahim Pratap (22 June 2013). "Unesco declares 6 Rajasthan forts World Heritage Sites". The Hindu. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger (2012). [Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places]. ISBN 1-136-63979-9. pp. 24.

- ^ "Amer Palace". Rajasthan Tourism: Government of India. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Jaigarh, the Invincible Fort of Amber. RBSA Publishers, 1990. 1990. p. 18. ISBN 9788185176482.

- ^ Jaipur: Gem of India. IntegralDMS, 2016. 7 July 2016. p. 24. ISBN 9781942322054.

- ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1994) [1984]. A History of Jaipur: C. 1503–1938. Orient Longman Limited. pp. 23, 24. ISBN 81-250-0333-9.

- ^ "Golden Triangle". mariatours.in. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.{{|date=October 2019|bot=InternetArchiveBot|fix-attempted=yes}}

- ^ R. S. Khangarot; P. S. Nathawat (1990). Jaigarh, the invincible fort of Amer. RBSA Publishers. pp. 8–9, 17. ISBN 978-81-85176-48-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Lindsay Brown; Amelia Thomas (2008). Rajasthan, Delhi & Agra. Lonely Planet. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-74104-690-8.

- ^ "Places around Jaipur". Archaeology Department of Rajasthan. Retrieved 17 April 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Information plaque at Jaleb Chowk". Archaeology Department of Rajasthan. Retrieved 17 April 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Information plaque on Ganesh Pol". Archaeology Department of Rajasthan. Retrieved 17 April 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ pareek, Amit Kumar Pareek and Agam kumar. "Sheesh mahal Amer palace". www.amerjaipur.in. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Information plaque on Zenani Deorhi". Archaeology Department of Rajasthan. Retrieved 17 April 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Heritage Status for Forts". Eastern Eye. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ "Iconic Hill Forts on UN Heritage List". New Delhi: Mail Today. 22 June 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ Ghosh, Rhea (2005). Gods in chains. Foundation Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-81-7596-285-9.

- ^ "Amer Palace renovation: Tampering with history?". The Times of India. 3 June 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Film crew drilled holes in Amer". The Times of India. 16 February 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Amber Fort center for elephant trafficking: Welfare board The Times of India, 18 December 2014

- ^ PETA takes up jumbo cause, seeks end to elephant ride at Amber, The Times of India, 11 December 2014

- ^ "Zachary Kussin, "Tour Cuts Indian Elephant Rides After PETA Reports Abuse," NY Post, 9 October 2017.

- ^ Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1833). "picture". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1834. Fisher, Son & Co.Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1833). "poetical illustration". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1834. Fisher, Son & Co.

Further reading

- Crump, Vivien; Toh, Irene (1996). Rajasthan (hardback). New York: Everyman Guides. p. 400. ISBN 1-85715-887-3.

- Michell, George; Martinelli, Antonio (2005). The Palaces of Rajasthan. London: Frances Lincoln. p. 271 pages. ISBN 978-0-7112-2505-3.

- Tillotson, G.H.R (1987). The Rajput Palaces – The Development of an Architectural Style (Hardback) (First ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 224 pages. ISBN 0-300-03738-4.