Sexism in American political elections

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Sexism in American political elections refers to how sexism impacts elections in the United States, ranging from influences on the supply, demand, and selection of candidates to electoral outcomes. Sexism is inherently a product of culture, as culture instills a certain set of beliefs or expectations for what constitutes appropriate behavior, appearance, or mannerisms based on a person's sex.[1] Sexism in American political elections is generally cited as a socially-driven obstacle to female political candidates, especially for non-incumbents, raising concerns about the representation of women in the politics of the United States.[2] Such prejudice can take varying forms, such as benevolent or hostile sexism—the latter stemming from fears of women threatening the power or leadership of men.[3]

Sexism and politics

[edit]

Sexism in the United States functions as a way to distribute power based on an individual's ability to meet gender expectations, and sexism typically rewards men over women—granting men more power and opportunities.[4] Although patriarchy is the dominant cultural practice in the United States, sexism exists as a process within this system that can also function separately and reward feminine behavior or appearance.[5] Sexism affects politics in broad ways that both reflect societal norms and influence social and political outcomes. Particularly when considering pushes for gender equality and other forms of social equality, achieving equal representation in political arenas has been viewed by some as a necessary prerequisite to change.[6] However, this goal is often challenged by a variety of societal gender roles, such as the expectation that women should be responsible for a disproportionate amount of household labor—a responsibility that has been termed the "Second Shift" by some scholars.[7] The current over-representation of men in elected offices can also embody sexism in politics. For some people, this may create the perception that men are naturally better leaders, thereby dissuading some women from considering running for office; conversely, the lack of equal representation can also be a strong motivating factor that has been partially attributed to election cycles with larger-than-normal numbers of women candidacies, like during the Year of the Woman.[8]

Although social factors can greatly influence the relationship between women and politics, institutions and systemic processes can also enable gendered results, and the election context also affects behavior.[9] Other politically marginalized groups in the United States, specifically racial and ethnic minorities, face similar obstacles as women when trying to achieve proportionate representation. While there are some electoral mechanisms, such as gerrymandering, that can offer a higher likelihood of at least some representation for these groups, this benefit does not extend to women as a demographic, as they are not similarly concentrated in certain geographic areas.[10] Moreover, the types of barriers faced by women are perceived differently by people of different political leanings. Democrats have been noted as more likely to consider systemic barriers as an issue for women, whereas Republicans are more likely to focus on individual-level barriers.[11]

Political recruitment model

[edit]The political recruitment model is often used to describe how women face sexism at different stages of the electoral process. The model first includes women that are 'eligible' to become prospective candidates, then those who actually consider becoming a candidate, followed by candidates themselves, and then, finally, those who successfully win an election and become a legislator or other elected official. Although studies have noted that the negative effects of gender for women gradually decrease across each stage of the model, fewer women than men progress all the way from being a person eligible to run to being an elected official.[12] Daniel M. Thomsen and Aaron S. King also make notes on the candidate political pool that there are nearly triple the amount of men running for candidacy in each party versus women.[13]

Sexism and aspirant candidates

[edit]Sexism has also been identified as having several impacts on aspirant candidates, ranging from their supply, to party demand, and internalized sexism. Studies have found that a person's sex is one of many significant predictors of likelihood to consider running for office, with men 50% more likely than women to engage in pre-campaign activities, such as learning about registration and other candidacy basics, even when accounting for differences in careers.[14] This disparity stems from a variety of factors, including perceptions among women that they would be more likely to face hostile sexism in the forms of voter hesitancy, lack of fair media coverage, or fundraising issues.[15] Women are also less likely to be encouraged to run for office, which can reduce the likelihood of moving from being an aspirant to an actual candidate.[16] The lack of equal representation for women also creates shortcomings in the availability of role models for aspirant candidates, which can be particularly detrimental for women of color.[17]

To better categorize these factors, researchers often refer to them as affecting the supply of, or demand for, women candidates. However, this kind of framing has also been found to be itself impactful on aspirant women. For women overall, framing the lack of equal representation as a supply issue has been found to decrease levels of political ambition, while framing this topic as a demand issue actually increases levels of ambition; notably, this trend has variations among racial and ethnic subsets of women.[18]

Supply of candidates

[edit]When considering the supply of women candidates, factors other than sexism and gender norms can also be influential. Some scholars have argued that a smaller supply of women candidates may partially stem from women making more strategic considerations about running in certain elections, such as if they view themselves as having a higher or lower likelihood of success.[19] However, other explanations of supply issues relate more explicitly to how gender socialization and segregated gender roles can limit the opportunities that women perceive as available.[20] These gendered perceptions can also influence how women perceive their own potential qualifications for elected office. In relation to men, women are more likely to both view themselves as less-qualified and consider qualifications very important for those who are considering becoming a candidate; together, these factors decrease the likelihood that a woman may choose to move beyond being just an aspirant—even if they are actually qualified—thereby reducing the supply of women candidates.[21]

Demand for candidates

[edit]The demand for women candidates is often described as factors that are external to women. Political parties and their leaders can act as gatekeepers that determine which aspirant candidates receive the most support—potentially resulting in sexist discrimination against women—and institutions can have similar limiting effects on prospective women candidates.[22] Demand issues also have pronounced impacts on the levels of political ambition among women. One study found that White and Asian women were more likely to have increased levels of political ambition when presented with demand explanations, while Black women were effected conversely, as their levels of ambition decreased in response to this kind of explanation; no significant effect was determined for Latinas.[23]

Sexism and transgender candidates

[edit]Transgender persons are significantly underrepresented in political positions, and only 0.1% of elected officials in the US openly identify as LGBTQ.[24] Given the scientifically proven psychological importance of role models, this shortage of LGBTQ officials may discourage trans and other members of the LGBTQ community from running for political offices in the future.[25]

Sexism and candidates

[edit]

For women that become electoral candidates, sexism can effect them in both perceived and tangible ways, including direct forms of discrimination and sexual objectification that stem from expected behavioral and appearance standards for women.[26] These forms of sexism can manifest in several different ways, such as when former vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin and presidential candidate Hillary Clinton were subjected to social expectations of beauty and stereotypically negative female traits.[27] Support provided by party elites and political networking are other areas where sexism may result in tangible impacts on the candidacies of women. Some studies have found that even though women believe that party elites will support them, the level of support may not be comparable to men; conversely, men were not found to believe that there are gendered differences in support from elites.[28] Given that elites in the US provide social and political capital to the candidates they support, this distinction can have significant implications for men and women candidates.[29] Moreover, women perceive male, as well as white, candidates as more easily navigating political networks and fundraising for their campaigns.[30] For women of color, intersectional barriers and stereotypes specific to their racial or ethnic group are viewed as particularly difficult to overcome.[31] These perceptions have been at least partially validated by related studies, which have found that women tend to receive less overall fundraising in comparison to white men and that men are more likely to be recruited by party elites.[32][31]

Female candidates tend to also be viewed as more caring compared to their male counterparts on certain issues, such as defense and the military, which can result in disadvantages for women when a topic is thought of as 'owned' by men. For example, in the 2016 presidential election, terrorism and national security were top priorities to the American public—possibly making it more difficult for female candidates to gain support around these issues.[33] Furthermore, women that reject traditional gender roles can be viewed as competent for executive positions but lacking in emotions, creating an unappealing image; when this image is reversed, women candidates that are viewed as caring and full of emotions subsequently become viewed as incompetent. This can result in a paradoxical situation where the women that follow traditional gender stereotypes, as well as those that reject them, end up struggling in political elections.[34] These stereotypes also become more prominent when women pursue executive-level elected positions that are higher-profile and seen as 'masculine.'[35] Benevolent sexism, or the view that women should be cared for by men, holds more positive stereotypes towards women but still places them in subordination to men, which can uphold perceptions that men should occupy political positions of power.[36]

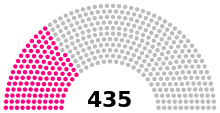

Likability

[edit]A key component of political campaigns is a candidate's likability.[37] Although likability applies to candidates of all gender identities, female candidates are disproportionately affected.[38] As of September 2019, women are underrepresented in Congress (24% of House and Senate seats are held by women, but they comprise over 50% of the United States population). Hurdles can exist in electing more women. Sociologist Marianne Cooper writes that women are judged in different ways than their male counterparts because “their very success violates our expectations about how women are supposed to behave."[39] She adds that the simple under-representation of women means that people do not have the ability to expect women in authority positions. This concept can be applied to government as well: because of female under-representation in government, female candidates are held to preexisting, oftentimes toxic, expectations, which in turn damage a candidate's likability.[40]

These expectations are oftentimes not straightforward.[37] Sexism can be expressed through both implicit and explicit means; this is reflected in how people view women in positions of authority, including female political candidates.[41] For example, explicit bias against women can be seen in attack ads that deride candidates for being feminists, as seen with former House candidate Amy McGrath.[42] An example of implicit gender bias is challenging a woman's credentials and qualifications, as seen in attacks against Senator Jacky Rosen's campaign.[42]

Sexism and elections

[edit]During elections, sexism can harm women candidates across a variety of key areas. When considering voter biases, party identification has been identified as one of the best predictors for whether or not a person will vote for a woman instead of a man.[43] This point has been bolstered by the fact that partisans have an extremely low probability of voting for candidates from the other party.[44] As a result, party preferences can override some potential avenues for increasing the descriptive representation of women. Additionally, one study noted that among independent voters, women candidates are more likely to receive support if they have a higher valence—which refers to non-policy characteristics, such as personality traits or skills—compared to their male competitors; without a higher perceived valence, women were found to have less support.[45] The study also noted that, in general, male independents seemed to prefer men candidates, while female independents did not have a clear gender preference—potentially indicating that in close elections where independents can determine the outcome, gender may be a particularly influential factor.[45]

Sexism and distributions of power are also increasingly present in high-stakes elections, such as presidential elections.[46] As the head of the Executive Branch, presidents have access to an extraordinary number of governmental abilities, including nominating Supreme Court Justices and vetoing bills passed by Congress; moreover, this position carries with it a symbolic and legitimate connection to the informal establishment of patriarchy.[47][48]

Though equal representation has still not been achieved, women are being elected more frequently than in the past, yet women of color remain underrepresented.[49] An exception to this trend comes from district racial composition. In districts with higher minority populations, women of color are more likely to be elected in comparison to white women—though these kinds of districts are a relatively small proportion of all congressional districts.[49]

Media coverage

[edit]

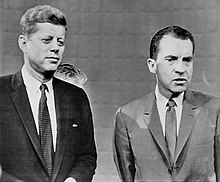

Since the first televised presidential debate in 1960, the rise of media, especially visual media, has had increased importance in political elections. By televising elections, more emphasis has been placed on the physical appearance of the candidates and how that reflected their perceived ability or skill. Furthermore, the idea of what a president looked like was cemented in American minds as a white male.[50] This type of coverage has only increased since the rise of social media, posing additional challenges to female candidates. They have difficulties getting equal news coverage compared to their male counterparts, receiving 50% less coverage.[51] When covered, the information emphasizes the personal traits of female candidates, such as physical appearance, rather than their positions on political issues.[52]

Research has also found that voters put more value in qualities seen as masculine and rank male candidates as more effective than their female counterparts who are similarly qualified.[53] But, when women try to use more traditionally masculine approaches, they are portrayed in the media as too angry or aggressive. This also crosses over into a female candidate's physical appearance. The Barbara Lee Family Foundation advised a “powerful yet approachable” look in a guidebook meant for female candidates, pointing to women's need to balance traits viewed as masculine and feminine.[54] Women politicians are also scrutinized in the media for their family lives. Female candidates without families are portrayed as not able to understand the average American family, while women with kids are seen as distracted by their additional responsibilities of motherhood.[53]

The prominence of presidential elections also enables a large amount of sexist media and discriminatory attack ads. The presidential election between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton has been considered a model for the effect of sexism in presidential election. Clinton, as the first female candidate to be nominated by one of the two major political parties, received a great deal of sexist portrayals and rhetoric from the media, as well as Trump's Campaign.[55]

Through media coverage, sexist tropes against female candidates can be amplified. Media platforms give pundits with sexism-laced rhetoric an opportunity to spread their messages.[56] During the 2008 presidential campaign, candidate Hillary Clinton began to tear up when speaking about her experiences running. In response, comedian Bill Maher said, “The first thing a woman does, of course, is cry,” despite all of the other campaign moments in which Clinton did not cry.[56]

Sexism and electoral outcomes

[edit]Given that sexism occurs throughout the electoral process, it influences not only the quality of elected women, but also the types of issues that become prioritized. In a study of US congresswomen, it was found that women secure almost 9% more federal spending for their districts than when those same districts were represented by men.[57] While several factors can explain this difference, the researchers argue that it is a result of how sexism pushes the most ambitious and talented women to pursue, and subsequently win, elected office.[58] Other scholars have noted that the increased representation of women can affect government spending levels. One study found that when increased representation occurred alongside greater female labor force participation, there was an association with higher levels of spending on family benefits.[59]

In addition to what was described in the last paragraph, additional scholars continue to research how sexism and the perception of women affects electoral outcomes. An article by Peter Bucchianeri discusses how Republican women lose general elections slightly more than Republican men, with no difference in outcomes among Democratic candidates.[60] Throughout the article, he theorizes that a lack in elite support in campaign funding is contributing to this gap, since Republican women on average fundraise slightly less money than their male counterparts. Bucchianeri suggests as a possible explanation that campaign donors are less likely to support female candidates on the Republican side, which perhaps denotes some sort of gender bias. With similar findings that support Bucchianeri's work, an article by Danielle Thomsen and Michael Sewers also concludes that women running electoral campaigns tend to have smaller donor networks than men.[61]

Another article by Ashley Sorenson and Philip Chen takes the analysis even further as it relates to campaign funding.[62] They argue that, "Women of color are systematically disadvantaged by the campaign finance system compared with white women and male candidates of color." This statement is made after an analysis of campaign finance receipts, in which they find women of color are systematically receiving less funding. This gap in funding likely has an impact on electoral outcomes for these women, and is theorized by Sorenson and Chen to be a result of sexism and racism.

Strategic Behavior and Electoral Outcomes for Female Candidates

[edit]Recent research highlights the strategic behavior of female candidates in navigating electoral processes shaped by gender norms and sexism. Studies indicate that women are not only less likely to run for office but also make highly strategic decisions when they do choose to run. For instance, Lawless and Fox (2018) discuss how perceived electoral environments influence women's decisions to enter races, particularly highlighting the impact of sexism on these perceptions.[63] This aligns with findings from Bucchianeri (2018), who notes that female candidates, especially in the Republican Party, tend to encounter and must navigate additional challenges such as reduced fundraising and support from political elites.[64] In a study conducted by Jordan Mansell, Allison Harell, Melanee Thomas, and Tania Gosselin, we also see obstacles with men having a negative reaction towards women when they are more successful than them. Resorting to hostile behavior and sexism toward women.[65]

Furthermore, Thomsen and Swers (2017) explore the gendered nature of candidate donor networks, revealing that women often face a narrower pathway to securing necessary campaign funds, which are crucial for electoral success.[66] This financial discrepancy underscores the broader systemic barriers that women encounter, which are not solely limited to individual instances of sexism but are embedded within the political recruitment and campaign finance systems.

The impact of these challenges is also evident in electoral outcomes. Sorenson and Chen (2022) provide a comprehensive analysis of campaign finance data, demonstrating that women of color are particularly disadvantaged, receiving less funding compared to their white and male counterparts, which affects their visibility and viability as candidates.[67] This systemic disadvantage is critical in understanding the intersectionality of sexism and racism in political elections.

Implications of outcomes

[edit]The increased representation of women also has broader implications for democracy, such as through an increased supply of political role models. Improved feelings of political efficacy, engagement, and attitudes toward government are also all associated with greater numbers of elected women.[68] These benefits are not limited to just one party, as elected women from both the Democratic and Republican Party have noted that electing more women provides a more diverse range of perspectives to Congress.[69]

References

[edit]- ^ Wallerstein, Immanuel (June 1990). "Culture as the Ideological Battleground of the Modern World-System". Theory, Culture & Society. 7 (2–3): 31–55. doi:10.1177/026327690007002003. hdl:10086/8420. ISSN 0263-2764. S2CID 55451025.

- ^ Rothwell, Valerie; Hodson, Gordon; Prusaczyk, Elvira (February 2019). "Why Pillory Hillary? Testing the endemic sexism hypothesis regarding the 2016 U.S. election". Personality and Individual Differences. 138: 106–108. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.034. S2CID 150309065.

- ^ "Supplemental Material for An Interdependence Account of Sexism and Power: Men's Hostile Sexism, Biased Perceptions of Low Power, and Relationship Aggression". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2018-11-19. doi:10.1037/pspi0000167.supp. ISSN 0022-3514. S2CID 239809214.

- ^ Acker, Joan (1973-01-01). "Women and Social Stratification: A Case of Intellectual Sexism". American Journal of Sociology. 78 (4): 936–945. doi:10.1086/225411. JSTOR 2776612. S2CID 143698982.

- ^ O'Neal; Egan, James; Jean (1993). Abuses of power against women: Sexism, gender role conflict, and psychological violence. Alexandria, VA, United States: American Counseling Association. pp. 49–78. ISBN 978-1-55620-100-4 – via EBSCO.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2020-01-01). "Women's Underrepresentation in the U.S. Congress". Daedalus. 149 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01772. ISSN 0011-5266. S2CID 209487865.

- ^ Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2020-01-01). "Women's Underrepresentation in the U.S. Congress". Daedalus. 149 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01772. ISSN 0011-5266. S2CID 209487865.

- ^ Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2020-01-01). "Women's Underrepresentation in the U.S. Congress". Daedalus. 149 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01772. ISSN 0011-5266. S2CID 209487865.

- ^ Schmitt, Carly, and Hanna K. Brant. 2019. “Gender, Ambition, and Legislative Behavior in the United States House.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 40 (2): 286-308.

- ^ English, Ashley; Pearson, Kathryn; Strolovitch, Dara Z. (2019-12-01). "Who Represents Me? Race, Gender, Partisan Congruence, and Representational Alternatives in a Polarized America". Political Research Quarterly. 72 (4): 785–804. doi:10.1177/1065912918806048. ISSN 1065-9129. S2CID 158576286.

- ^ Dolan, Kathleen; Hansen, Michael (2018). "Blaming Women or Blaming the System? Public Perceptions of Women's Underrepresentation in Elected Office". Political Research Quarterly. 71 (3): 668–680. doi:10.1177/1065912918755972. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 45106690. S2CID 149220469.

- ^ Fox, Richard L.; Lawless, Jennifer L. (2004). "Entering the Arena? Gender and the Decision to Run for Office". American Journal of Political Science. 48 (2): 264–280. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00069.x. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ^ Thomsen, Danielle M., and Aaron S. King. 2020. “Women’s Representation and the Gendered Pipeline to Power.” American Political Science Review 114 (4): 989-1000.

- ^ Fox, Richard L.; Lawless, Jennifer L. (2004). "Entering the Arena? Gender and the Decision to Run for Office". American Journal of Political Science. 48 (2): 264–280. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00069.x. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ^ Dolan, Kathleen; Hansen, Michael (2018). "Blaming Women or Blaming the System? Public Perceptions of Women's Underrepresentation in Elected Office". Political Research Quarterly. 71 (3): 668–680. doi:10.1177/1065912918755972. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 45106690. S2CID 149220469.

- ^ Fox, Richard L.; Lawless, Jennifer L. (2004). "Entering the Arena? Gender and the Decision to Run for Office". American Journal of Political Science. 48 (2): 264–280. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00069.x. JSTOR 1519882.

- ^ Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2015). "Electing Women of Color: The Role of Campaign Trainings". Journal of Women, Politics & Policy. 36 (2): 137–160. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2015.1019273. S2CID 143227673.

- ^ Holman, Mirya R.; Schneider, Monica C. (2018-04-03). "Gender, race, and political ambition: how intersectionality and frames influence interest in political office". Politics, Groups, and Identities. 6 (2): 264–280. doi:10.1080/21565503.2016.1208105. ISSN 2156-5503. S2CID 147854693.

- ^ Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2020-01-01). "Women's Underrepresentation in the U.S. Congress". Daedalus. 149 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01772. ISSN 0011-5266. S2CID 209487865.

- ^ Holman, Mirya R.; Schneider, Monica C. (2018-04-03). "Gender, race, and political ambition: how intersectionality and frames influence interest in political office". Politics, Groups, and Identities. 6 (2): 264–280. doi:10.1080/21565503.2016.1208105. ISSN 2156-5503. S2CID 147854693.

- ^ Fox, Richard L.; Lawless, Jennifer L. (2004). "Entering the Arena? Gender and the Decision to Run for Office". American Journal of Political Science. 48 (2): 264–280. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00069.x. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ^ Holman, Mirya R.; Schneider, Monica C. (2018-04-03). "Gender, race, and political ambition: how intersectionality and frames influence interest in political office". Politics, Groups, and Identities. 6 (2): 264–280. doi:10.1080/21565503.2016.1208105. ISSN 2156-5503. S2CID 147854693.

- ^ Holman, Mirya R.; Schneider, Monica C. (2018-04-03). "Gender, race, and political ambition: how intersectionality and frames influence interest in political office". Politics, Groups, and Identities. 6 (2): 264–280. doi:10.1080/21565503.2016.1208105. ISSN 2156-5503. S2CID 147854693.

- ^ "A Census of Out LGBTQ Elected Officials Nationwide" (PDF). Victory Institute. 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Marx, David (2002). "Female Role Models: Protecting Women's Math Test Performance". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 28 (9): 1183–1193. doi:10.1177/01461672022812004. S2CID 19258680.

- ^ Smith, Kevin B. (1997-01-01). "When All's Fair: Signs of Parity in Media Coverage of Female Candidates". Political Communication. 14 (1): 71–82. doi:10.1080/105846097199542. ISSN 1058-4609.

- ^ Osborn, Tracy (2012-01-01). "Review of Hillary Clinton's Race for the White House: Gender Politics and the Media on the Campaign Trail". Perspectives on Politics. 10 (1): 184–186. doi:10.1017/S153759271100452X. JSTOR 23327101. S2CID 145577549.

- ^ Butler, Daniel M.; Preece, Jessica Robinson (2016). "Recruitment and Perceptions of Gender Bias in Party Leader Support". Political Research Quarterly. 69 (4): 842–851. doi:10.1177/1065912916668412. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 44018061. S2CID 157460168.

- ^ Butler, Daniel M.; Preece, Jessica Robinson (2016). "Recruitment and Perceptions of Gender Bias in Party Leader Support". Political Research Quarterly. 69 (4): 842–851. doi:10.1177/1065912916668412. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 44018061. S2CID 157460168.

- ^ Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2015). "Electing Women of Color: The Role of Campaign Trainings". Journal of Women, Politics & Policy. 36 (2): 137–160. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2015.1019273. S2CID 143227673.

- ^ a b Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2015). "Electing Women of Color: The Role of Campaign Trainings". Journal of Women, Politics & Policy. 36 (2): 137–160. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2015.1019273. S2CID 143227673.

- ^ Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2020-01-01). "Women's Underrepresentation in the U.S. Congress". Daedalus. 149 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01772. ISSN 0011-5266. S2CID 209487865.

- ^ Valentino, Nicholas A; Wayne, Carly; Oceno, Marzia (2018-04-11). "Mobilizing Sexism: The Interaction of Emotion and Gender Attitudes in the 2016 US Presidential Election". Public Opinion Quarterly. 82 (S1): 799–821. doi:10.1093/poq/nfy003. ISSN 0033-362X.

- ^ Bock, Jarrod (2017). "The Role of Sexism in Voting in the 2016 Presidential Election". Personality and Individual Differences. 119: 189–193. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.026.

- ^ Knuckey, Jonathan (February 2019). ""I Just Don't Think She Has a Presidential Look": Sexism and Vote Choice in the 2016 Election*: Sexism and Vote Choice". Social Science Quarterly. 100 (1): 342–358. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12547.

- ^ Cassese, Erin C.; Holman, Mirya R. (February 2019). "Playing the Woman Card: Ambivalent Sexism in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Race: Playing the Woman Card". Political Psychology. 40 (1): 55–74. doi:10.1111/pops.12492. S2CID 150018545.

- ^ a b Krupnikov, Yanna (April 2015). "Saving Face: Identifying Voter Responses to Black Candidates and Female Candidates". Political Psychology. 37.

- ^ Mendoza, Saaid (January 2019). "Not "With Her": How Gendered Political Slogans Affect Conservative Women's Perceptions of Female Leaders". Sex Roles. 80 (1–2): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0910-z. S2CID 149514119 – via GenderWatch.

- ^ Cooper, Marianne (April 30, 2013). "For Women Leaders, Likability and Success Hardly Go Hand-in-Hand". Harvard Business Review.

- ^ Sapiro, Virginia (Summer 1982). "If U.S. Senator Baker Were A Woman: An Experimental Study of Candidate Images". Political Psychology. 3 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Rudman, Laurie (November 2000). "Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Female Authority". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 26 (11): 1315–1328. doi:10.1177/0146167200263001. S2CID 6962810 – via SAGE Journals.

- ^ a b Newburger, Emma (September 27, 2018). "Female candidates in 2018 more aggressively calling out sexism on the campaign trail". NBC.

- ^ Dolan, Kathleen; Hansen, Michael (2018). "Blaming Women or Blaming the System? Public Perceptions of Women's Underrepresentation in Elected Office". Political Research Quarterly. 71 (3): 668–680. doi:10.1177/1065912918755972. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 45106690. S2CID 149220469.

- ^ Fulton, Sarah A. (2014). "When Gender Matters: Macro-dynamics and Micro-mechanisms". Political Behavior. 36 (3): 605–630. doi:10.1007/s11109-013-9245-1. ISSN 0190-9320. JSTOR 43653408. S2CID 143736984.

- ^ a b Fulton, Sarah A. (2014). "When Gender Matters: Macro-dynamics and Micro-mechanisms". Political Behavior. 36 (3): 605–630. doi:10.1007/s11109-013-9245-1. ISSN 0190-9320. JSTOR 43653408. S2CID 143736984.

- ^ Heldman, Caroline (2009-08-22). "From Ferraro to Palin: Sexism in Media Coverage of Vice Presidential Candidates". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1459865. SSRN 1459865.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Anonymous (2000). "A Few Good Men". National Review. 53: 14 – via EBSCO.

- ^ Rebick, Judy (2005). "Propping Up the Patriarchy". Herizons: 5 – via EBSCO.

- ^ a b Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2015). "Electing Women of Color: The Role of Campaign Trainings". Journal of Women, Politics & Policy. 36 (2): 137–160. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2015.1019273. S2CID 143227673.

- ^ You've Come A Long Way, Baby: Women, Politics, and Popular Culture. University Press of Kentucky. 2009. ISBN 9780813125442. JSTOR j.ctt2jcnsv.

- ^ Uscinski, Joseph E.; Goren, Lilly J. (2011). "What's in a Name? Coverage of Senator Hillary Clinton during the 2008 Democratic Primary". Political Research Quarterly. 64 (4): 884–896. doi:10.1177/1065912910382302. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 23056354. S2CID 153646157.

- ^ Dunaway, Johanna; Lawrence, Regina G.; Rose, Melody; Weber, Christopher R. (2013). "Traits versus Issues: How Female Candidates Shape Coverage of Senate and Gubernatorial Races". Political Research Quarterly. 66 (3): 715–726. doi:10.1177/1065912913491464. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 23563177. S2CID 145273060.

- ^ a b Women and the White House: Gender, Popular Culture, and Presidential Politics. University Press of Kentucky. 2013. ISBN 9780813141015. JSTOR j.ctt2jck4s.

- ^ "Keys to Elected Office: The Essential Guide for Women (2017)". Barbara Lee Family Foundation. 2 June 2016. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ "Sexism in Politics 2016: What can we learn so far from media portrayals of Hillary Clinton and Latin American female leaders?". COHA. 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ^ a b Lawless, Jennifer (March 2009). "Sexism and Gender Bias in Election 2008: A More Complex Path for Women in Politics". Politics and Gender. 5 – via GenderWatch.

- ^ Anzia, Sarah F.; Berry, Christopher R. (2011). "The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson Effect: Why Do Congresswomen Outperform Congressmen?". American Journal of Political Science. 55 (3): 478–493. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00512.x. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ^ Anzia, Sarah F.; Berry, Christopher R. (2011). "The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson Effect: Why Do Congresswomen Outperform Congressmen?". American Journal of Political Science. 55 (3): 478–493. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00512.x. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ^ Ennser-Jedenastik, Laurenz (2017). "How Women's Political Representation affects Spending on Family Benefits". Journal of Social Policy. 46 (3): 563–581. doi:10.1017/S0047279416000933. ISSN 0047-2794. S2CID 151449118.

- ^ Bucchianeri, Peter (2018). "Is Running Enough? Reconsidering the Conventional Wisdom about Women Candidates". Political Behavior. 40 (2): 435–466. doi:10.1007/s11109-017-9407-7.

- ^ Thomsen, Danielle M.; Swers, Michele L. (2017). "Which Women Can Run? Gender, Partisanship, and Candidate Donor Networks". Political Research Quarterly. 70 (2): 449–463. doi:10.1177/1065912917698044. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 26384954.

- ^ Sorensen, Ashley, and Philip Chen. 2022. “Identity in Campaign Finance and Elections: The Impact of Gender and Race on Money Raised in 2010-2018 U.S. House Elections.” Political Research Quarterly 75 (3): 738-753.

- ^ Lawless, Jennifer L., and Richard L. Fox. 2018. “Triumph and Defeat: Election 2016 and the State of Contemporary Feminism.” Chapter 1.

- ^ Bucchianeri, Peter. 2018. “Is Running Enough? Reconsidering the Conventional Wisdom about Women Candidates.” Political Behavior 40 (2): 435-66.

- ^ Mansell, Jordan, Allison Harell, Melanee Thomas, and Tania Gosselin. 2022. “Competitive Loss, Gendered Backlash, and Sexism in Politics. Political Behavior 44 (2): 455-476.

- ^ Thomsen, Danielle M., and Michele L. Swers. 2017. “Which Women Can Run? Gender, Partisanship, and Candidate Donor Networks.” Political Research Quarterly 70 (2): 449-463.

- ^ Sorenson, Ashley, and Philip Chen. 2022. “Identity in Campaign Finance and Elections: The Impact of Gender and Race on Money Raised in 2010-2018 U.S. House Elections.” Political Research Quarterly 75 (3): 738-753.

- ^ English, Ashley; Pearson, Kathryn; Strolovitch, Dara Z. (2019-12-01). "Who Represents Me? Race, Gender, Partisan Congruence, and Representational Alternatives in a Polarized America". Political Research Quarterly. 72 (4): 785–804. doi:10.1177/1065912918806048. ISSN 1065-9129. S2CID 158576286.

- ^ Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2020-01-01). "Women's Underrepresentation in the U.S. Congress". Daedalus. 149 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01772. ISSN 0011-5266. S2CID 209487865.