Alaska Purchase

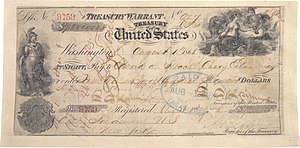

The US$7.2 million check used to pay for Alaska (equivalent to $129 million in 2023)[1] | |

| Signed | March 30, 1867 |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Ratified | May 15, 1867 |

| Effective | October 18, 1867 |

| Signatories | |

| Languages |

|

The Alaska Purchase was the purchase of Alaska from the Russian Empire by the United States for a sum of $7.2 million in 1867 (equivalent to $129 million in 2023)[1]. On May 15 of that year, the United States Senate ratified a bilateral treaty that had been signed on March 30, and American sovereignty became legally effective across the territory on October 18.

During the first half of the 18th century, Russia had established a colonial presence in parts of North America, but few Russians ever settled in Alaska. Alexander II of Russia, having faced a catastrophic defeat in the Crimean War, began exploring the possibility of selling the state's Alaskan possessions, which, in any future war, would be difficult to defend from the United Kingdom. To this end, William H. Seward, the U.S. Secretary of State at the time, entered into negotiations with Russian diplomat Eduard de Stoeckl towards the United States' acquisition of Alaska after the American Civil War. Seward and Stoeckl agreed to a treaty for the sale on March 30, 1867.

At an original cost of $0.02 per acre ($0.36 per acre in 2023), the United States had grown by 586,412 sq mi (1,518,800 km2).[1] Reactions to the Alaska Purchase among Americans were mostly positive, as many believed that Alaska would serve as a base to expand American trade in Asia. Some opponents labeled the purchase as "Seward's Folly" or "Seward's Icebox"[2] as they contended that the United States had acquired useless land. Nearly all Russian settlers left Alaska in the aftermath of the purchase; Alaska would remain sparsely populated until the Klondike Gold Rush began in 1896. Originally organized as the Department of Alaska, the area was renamed the District of Alaska in 1884 and the Territory of Alaska in 1912, ultimately becoming the modern-day State of Alaska in 1959.

History

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| History of Alaska |

|---|

|

|

Russian America was settled by promyshlenniki, merchants and fur trappers who expanded through Siberia. They arrived in Alaska in 1732, and in 1799 the Russian-American Company (RAC) received a charter to hunt for fur. No colony was established, but the Russian Orthodox Church sent missionaries to the natives and built churches. About 700 Russians enforced sovereignty in a territory over twice as large as Texas.[3] In 1821, Tsar Alexander I issued an edict declaring Russia's sovereignty over the North American Pacific coast north of the 51st parallel north. The edict also forbade foreign ships to approach within 100 Italian miles (115 miles or 185 km) of the Russian claim. US Secretary of State John Quincy Adams strongly protested the edict, which potentially threatened both the commerce and expansionary ambitions of the United States. Seeking favorable relations with the U.S., Alexander agreed to the Russo-American Treaty of 1824. In the treaty, Russia limited its claims to lands north of parallel 54°40′ north and also agreed to open Russian ports to U.S. ships.[4]

By the 1850s, a population of once 300,000 sea otters was almost extinct, and Russia needed money after being defeated by France and Britain in the Crimean War. The California Gold Rush showed that if gold were discovered in Alaska, Americans and Canadians would overwhelm the Russian presence in what one scholar later described as "Siberia's Siberia".[3] However, the principal reason for the sale was that the hard-to-defend colony would be easily conquered by British forces based in neighboring Canada in any future conflict, and Russia did not wish to see its archrival being next door just across the Bering Sea. Therefore, Emperor Alexander II decided to sell the territory. The Russian government discussed the proposal in 1857 and 1858[5] and offered to sell the territory to the United States, hoping that its presence in the region would offset the plans of Britain. However, no deal was reached, as the risk of an American Civil War was a more pressing concern in Washington.[6][7]

Grand Duke Konstantin, a younger brother of the Tsar, began to press for the handover of Russian America to the United States in 1857. In a memorandum to Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov he stated that

we must not deceive ourselves and must foresee that the United States, aiming constantly to round out their possessions and desiring to dominate undividedly the whole of North America will take the afore-mentioned colonies from us and we shall not be able to regain them.[5]

Konstantin's letter was shown to his brother, Tsar Alexander II, who wrote "this idea is worth considering" on the front page.[8] Supporters of Konstantin's proposal to immediately withdraw from North America included Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin and the Russian minister to the United States, Eduard de Stoeckl. Gorchakov agreed with the necessity of abandoning Russian America but argued for a gradual process leading to its sale. He found a supporter in the naval minister and former chief manager of the Russian-American Company, Ferdinand von Wrangel. Wrangel pressed for some proceeds to be invested in the economic development of Kamchatka and the Amur Basin.[8] The Emperor eventually sided with Gorchakov, deciding to postpone negotiations until the end of the RAC's patent, set to expire in 1861.

Over the winter of 1859–1860, Stoeckl held meetings with United States officials, though he had been instructed not to initiate discussions about the sale of the RAC assets. Communicating primarily with Assistant Secretary of State John Appleton and California Senator William M. Gwin, Stoeckl reported the interest expressed by the Americans in acquiring Russian America. While President James Buchanan kept these hearings informal, preparations were made for further negotiations.[8] Stoeckl reported a conversation in which he asked "in passing" what price the U.S. government might pay for the Russian colony and Senator Gwin replied that they "might go as far as $5,000,000", a figure Gorchakov found far too low. Stoeckl informed Appleton and Gwin of this, the latter saying that his Congressional colleagues in Oregon and California would support a larger figure. Buchanan's increasingly unpopular presidency forced the matter to be shelved until a new presidential election. With the oncoming American Civil War, Stoeckl proposed a renewal of the RAC's charter. Two of its ports were to be open to foreign traders and commercial agreements with Peru and Chile to be signed to give "a fresh jolt" to the company.[8]

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for full text of ratification.

Wikimedia Commons has a file available for full text of ratification.Russia continued to see an opportunity to weaken British power by causing British Columbia, including the Royal Navy base at Esquimalt, to be surrounded or annexed by American territory.[9] Following the Union victory in the Civil War in 1865, the Tsar instructed Stoeckl to re-enter into negotiations with William H. Seward in the beginning of March 1867. President Andrew Johnson was busy with negotiations about Reconstruction, and Seward had alienated a number of Republicans, so both men believed that the purchase would help divert attention from domestic issues.[10] The negotiations concluded after an all-night session with the signing of the treaty at 04:00 on March 30, 1867.[11] The purchase price was set at $7.2 million (equivalent to $129 million in 2023),[1] or about 2 cents per acre ($4.74/km2).[1][12]

American ownership

[edit]The Russian name for the Alaska Peninsula was Alyaska ("Аляска") or Alyeska, from an Aleut word, alashka or alaesksu, meaning "great land"[13] or "mainland".[14] The United States chose the name "Alaska" to refer to the area purchased from Russia.

Seward told the nation that, according to Russian estimates, Alaska had about 60,000 inhabitants. This included about 10,500 who were under the direct government of the Russian fur company: about 8,000 indigenous people and 2,500 people of Russian or mixed Russian and indigenous descent (for example, having a Russian father and a native mother). The remaining 50,000 or so were Inuit or Alaska Natives living outside of Russia's jurisdiction.

Seward also said that the Russians were settled at 23 trading posts, placed on accessible islands and at points along the coast. At smaller trading posts, typically only four or five Russians were stationed: their job was to collect furs from the natives for storage and then for shipment when the company's boats arrived to take the furs away. There were two larger towns. One was New Archangel (now named Sitka), established in 1804 to handle the valuable trade in the skins of sea otters; in 1867, it had 116 small log cabins and 968 residents. The other was St. Paul, in the Pribilof Islands, which had 100 homes and 283 residents, and was the center of the seal fur industry.[15]

Seward and many other Americans expected that Asia would become an important market for U.S. products, and that Alaska would serve as a base for American trade with Asia and globally, and for the extension of American power into the Pacific.

Senator Charles Sumner, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, sponsored the Senate bill authorizing the U.S. to approve the treaty to acquire the territory. He not only agreed about the benefit to trade, but also said he expected the territory to be valuable on its own; having studied the records of explorers, he believed it contained valuable animals and forests. He compared the acquisition to contemporary European colonial acquisitions, such as the French conquest of Algeria.[16][17] The United States Senate approved the treaty by a vote of 37 to 2.[18]

Public opinion favors the purchase

[edit]Many Americans believed in 1867 that the purchase process had been corrupt,[17] but W. H. Dall in 1872 wrote that, "there can be no doubt that the feelings of a majority of the citizens of the United States are in favor of it."[19] The notion that the purchase was unpopular among Americans is, a scholar wrote 120 years later, "one of the strongest historical myths in American history. It persists despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, and the efforts of the best historians to dispel it", likely in part because it fits American and Alaskan writers' view of the territory as distinct and filled with self-reliant pioneers.[16]

A majority of newspapers either supported the purchase or were neutral.[17] A review of dozens of contemporary newspapers found general support for the purchase, especially in California; most of 48 major newspapers supported the purchase.[16][20] Public opinion was not universally positive; to some the purchase was known as "Seward's folly", "Walrussia",[3] or "Seward's icebox". Editorials contended that taxpayer money had been wasted on a "polar bear garden". Nonetheless, most newspaper editors argued that the U.S. would probably derive great economic benefits from the purchase, such as considerable mineral resources that previous geological explorations of the region suggested were available there;[21] friendship with Russia was important; and it would facilitate the acquisition of British Columbia.[22][23][24][25] Forty-five percent of supportive newspapers cited the increased potential for annexing British Columbia in their support,[9] and The New York Times stated that, consistent with Seward's reason, Alaska would increase American trade with East Asia.[17]

The principal urban newspaper that opposed the purchase was the New York Tribune, published by Seward opponent Horace Greeley. The ongoing controversy over Reconstruction spread to other acts, including the Alaska purchase. Some opposed the United States obtaining its first non-contiguous territory, seeing it as a colony; others saw no need to pay for land that they expected the country to obtain through manifest destiny.[16] Historian Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer summarized the minority opinion of some American newspaper editors who opposed the purchase:[26]

Already, so it was said, we were burdened with territory we had no population to fill. The Indians within the present boundaries of the republic strained our power to govern aboriginal peoples. Could it be that we would now, with open eyes, seek to add to our difficulties by increasing the number of such peoples under our national care? The purchase price was small; the annual charges for administration, civil and military, would be yet greater, and continuing. The territory included in the proposed cession was not contiguous to the national domain. It lay away at an inconvenient and a dangerous distance. The treaty had been secretly prepared, and signed and foisted upon the country at one o'clock in the morning. It was a dark deed done in the night… The New York World said that it was a "sucked orange." It contained nothing of value but furbearing animals, and these had been hunted until they were nearly extinct. Except for the Aleutian Islands and a narrow strip of land extending along the southern coast the country would be not worth taking as a gift… Unless gold were found in the country much time would elapse before it would be blessed with Hoe printing presses, Methodist chapels and a metropolitan police. It was "a frozen wilderness."

— Oberholtzer

Transfer ceremony

[edit]

The transfer ceremony took place in Sitka on October 18, 1867. Russian and American soldiers paraded in front of the governor's house; the Russian flag was lowered and the American flag raised amid peals of artillery.

A description of the events was published in Finland six years later. It was written by a blacksmith named Thomas Ahllund, who had been recruited to work in Sitka:[27]

We had not spent many weeks at Sitka when two large steam ships arrived there, bringing things that belonged to the American crown, and a few days later the new governor also arrived in a ship together with his soldiers. The wooden two-story mansion of the Russian governor stood on a high hill, and in front of it in the yard at the end of a tall spar flew the Russian flag with the double-headed eagle in the middle of it. Of course, this flag now had to give way to the flag of the United States, which is full of stripes and stars. On a predetermined day in the afternoon, a group of soldiers came from the American ships, led by one who carried the flag. Marching solemnly, but without accompaniment, they came to the governor's mansion, where the Russian troops were already lined up and waiting for the Americans. Now they started to pull the [Russian double-headed] eagle down, but—whatever had gone into its head—it only came down a little bit, and then entangled its claws around the spar so that it could not be pulled down any further. A Russian soldier was therefore ordered to climb up the spar and disentangle it, but it seems that the eagle cast a spell on his hands, too—for he was not able to arrive at where the flag was, but instead slipped down without it. The next one to try was not able to do any better; only the third soldier was able to bring the unwilling eagle down to the ground. While the flag was brought down, music was played and cannons were fired off from the shore, and then, while the other flag was hoisted, the Americans fired off their cannons from the ships equally many times. After that American soldiers replaced the Russian ones at the gates of the fence surrounding the Kolosh [i.e. Tlingit] village.

After the flag transition was completed, Captain of 2nd Rank Aleksei Alekseyevich Peshchurov said, "General Rousseau, by authority from His Majesty, the Emperor of Russia, I transfer to the United States the territory of Alaska." General Lovell Rousseau accepted the territory. (Peshchurov had been sent to Sitka as commissioner of the Russian government in the transfer of Alaska.) A number of forts, blockhouses and timber buildings were handed over to the Americans. The troops occupied the barracks; General Jefferson C. Davis established his residence in the governor's house, and most of the Russian citizens went home, leaving a few traders and priests who chose to remain.[28][29]

Aftermath

[edit]After the transfer, a number of Russian citizens remained in Sitka, but nearly all of them very soon decided to return to Russia, which was still possible at the expense of the Russian-American Company. Ahllund's story "corroborates other accounts of the transfer ceremony, and the dismay felt by many of the Russians and creoles, jobless and in want, at the rowdy troops and gun-toting civilians who looked on Sitka as merely one more western frontier settlement." Ahllund gives a vivid account of what life was like for civilians in Sitka under US rule and helps to explain why hardly any Russian subject wanted to stay there. Moreover, Ahllund's article is the only known description of the return voyage on the Winged Arrow, a ship that was specially purchased to transport the Russians back to their native country. "The over-crowded vessel, with crewmen who got roaring drunk at every port, must have made the voyage a memorable one." Ahllund mentions stops at the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands, Tahiti, Brazil, London, and finally Kronstadt, the port for St. Petersburg, where they arrived on August 28, 1869.[30]

American settlers who shared Sumner's belief in the riches of Alaska rushed to the territory but found that much capital was required to exploit its resources, many of which could also be found closer to markets in the contiguous United States. Most soon left, and by 1873, Sitka's population had declined from about 2,500 to a few hundred.[16] The United States acquired an area over twice as large as Texas, but it was not until the great Klondike Gold Rush in 1896 that Alaska generally came to be seen as a valuable addition to U.S. territory.

The seal fishery was one of the chief considerations that induced the United States to purchase Alaska. It provided considerable revenue by the lease of the privilege of taking seals, an amount that was eventually more than the price paid for Alaska. From 1870 to 1890, the seal fisheries yielded 100,000 skins a year. The company to which the administration of the fisheries was entrusted by a lease from the US government paid a rental of $50,000 per annum and in addition thereto $2.62+1⁄2 per skin for the total number taken. The skins were transported to London to be dressed and prepared for world markets. The business grew so large that the earnings of English laborers after the acquisition of Alaska by the United States amounted by 1890 to $12,000,000.[31]

However, exclusive US control of this resource was eventually challenged, and the Bering Sea Controversy resulted when the United States seized over 150 sealing ships flying the British flag, based out of the coast of British Columbia. The conflict between the United States and Britain was resolved by an arbitration tribunal in 1893. The waters of the Bering Sea were deemed to be international waters, contrary to the US contention that they were an internal sea. The US was required to make a payment to Britain, and both nations were required to follow regulations developed to preserve the resource.[31]

Financial return

[edit]The purchase of Alaska has been referenced as a "bargain basement deal"[32] and as the principal positive accomplishment of the otherwise much-maligned presidency of Andrew Johnson.[33][34]

Economist David R. Barker has argued that the US federal government has not earned a positive financial return on the purchase of Alaska. According to Barker, tax revenue and mineral and energy royalties to the federal government have been less than federal costs of governing Alaska plus interest on the borrowed funds used for the purchase.[35]

John M. Miller has taken the argument further by contending that US oil companies that developed Alaskan petroleum resources did not earn enough profits to compensate for the risks that they incurred.[36]

Other economists and scholars, including Scott Goldsmith and Terrence Cole, have criticized the metrics used to reach those conclusions by noting that most contiguous Western states would fail to meet the bar of "positive financial return" using the same criteria and by contending that looking at the increase in net national income, instead of only US Treasury revenue, would paint a much more accurate picture of the financial return of Alaska as an investment.[37]

Alaska Day

[edit]Alaska Day celebrates the formal transfer of Alaska from Russia to the United States, which took place on October 18, 1867, according to the Gregorian calendar which came into effect in Alaska the day following the transfer, replacing the Julian calendar, which was used by the Russians (the Julian calendar in the 19th century was 12 days behind the Gregorian calendar). Alaska Day is a holiday for all state workers.[38]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ "Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska", Primary Documents in American History, The Library of Congress, April 25, 2017. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c Montaigne, Fen (July 7, 2016). "Tracing Alaska's Russian Heritage". Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ Herring, pp. 151–153, 157.

- ^ a b Russian Opinion on the Cession of Alaska. The American Historical Review 48, No. 3 (1943), pp. 521–531.

- ^ "Purchase of Alaska, 1867". Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ Claus-M Naske; Herman E. Slotnick (1994). Alaska: A History of the 49th State. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-8061-2573-2.

- ^ a b c d Bolkhovitinov, Nikolay N. (1990). "The Crimean War and the Emergence of Proposals for the Sale of Russian America, 1853–1861". Pacific Historical Review. 59 (1): 15–49. doi:10.2307/3640094. JSTOR 3640094.

- ^ a b Neunherz, R. E. (1989). ""Hemmed In": Reactions in British Columbia to the Purchase of Russian America". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 80 (3): 101–111. JSTOR 40491056.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert C. "The Big Thing". Harp Week. Archived from the original on March 26, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Seward, Frederick W., Seward at Washington as Senator and Secretary of State. Volume: 3, 1891, p. 348.

- ^ "Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Sandy Nestor, Indian Placenames in America, Vol. 1 (2015), p. 11

- ^ Elspeth Leacock, The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill (2009), p. 14

- ^ Seward (1869).

- ^ a b c d e Haycox, Stephen (1990). "Truth and Expectation: Myth in Alaska History". Northern Review. 6: 59–82. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Cook, Mary Alice (Spring 2011). "Manifest Opportunity: The Alaska Purchase as a Bridge Between United States Expansion and Imperialism" (PDF). Alaska History. 26 (1): 1–10.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875". loc.gov.

- ^ Dall, W. H. (1872). "Is Alaska a Paying Investment". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. XLIV. NY: Harper & Brothers: 252.

- ^ Jones, Preston (2013). The fires of patriotism: Alaskans in the days of the First World War 1910–1920. Illustrations edited by Neal Holland. University of Alaska Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-60223-205-1. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ New Orleans Times, April 10, 1867

- ^ Welch, Richard E. Jr. (1958). "American Public Opinion and the Purchase of Russian America". American Slavic and East European Review. 17 (4): 481–494. doi:10.2307/3001132. JSTOR 3001132.

- ^ Kushner, Howard I. (1975). "'Seward's Folly'?: American Commerce in Russian America and the Alaska Purchase". California Historical Quarterly. 54 (1): 4–26. doi:10.2307/25157541. JSTOR 25157541.

- ^ "Biographer calls Seward's Folly a myth". The Seward Phoenix LOG. April 3, 2014. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Founding of Anchorage, Alaska (Adobe Flash). Featured Speaker, Professor Preston Jones. C-SPAN. July 9, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, A History of the United States since the Civil War (1917) 1:541.

- ^ Ahllund, T. (1873/2006).

- ^ Bancroft, H. H., (1885) pp. 590–629.

- ^ Pierce, R. (1990), p. 395.

- ^ Richard Pierce, introduction to Ahllund, T., From the Memoirs of a Finnish Workman (2006).

- ^ a b Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^ "Seward's Folly: Who's Laughing Now?", by Karen Harris, History Daily, January 2, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ "Why the Purchase of Alaska Was Far From "Folly", by Jesse Greenspan, History.com, September 3, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ "Purchase of Alaska, 1867", Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs of the United States. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ Powell, Michael (August 18, 2010). "How Alaska Became a Federal Aid Magnet". The New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Miller, John (2010). The Last Alaskan Barrel: An Arctic Oil Bonanza that Never Was. Caseman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9828780-0-2.

- ^ Powell, Michael (August 20, 2010). "Was the Alaska Purchase a Good Deal?". The New York Times. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ State of Alaska 2014 Holiday Calendar (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on August 20, 2014, retrieved December 18, 2014

Sources

[edit]- Bailey, Thomas A. (March 1934). "Why the United States Purchased Alaska". Pacific Historical Review. 3 (1): 39–49. doi:10.2307/3633456. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3633456.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). History of Alaska, 1730-1885. The works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. Vol. XXXIII. San Francisco, Calif: A.L. Bancroft & Co. OCLC 20520463.

- Doyle, Don Harrison (2024). The age of Reconstruction: how Lincoln's new birth of freedom remade the world. America in the world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 99–120. ISBN 978-0-691-25609-2.

- Dunning, Wm. A. (September 1, 1912). "Paying for Alaska". Political Science Quarterly. 27 (3): 385–398. doi:10.2307/2141366. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2141366.

- Farrow, Lee A. (2016). Seward's folly: a new look at the Alaska Purchase. Fairbanks (Ala.): University of Alaska Press. ISBN 978-1-60223-303-4.

- Gibson, James R. (1979). "Why the Russians Sold Alaska". The Wilson Quarterly. 3 (3): 179–188. ISSN 0363-3276. JSTOR 40255691.

- Grinëv, Andrei V.; Bland, Richard L. (May 2010). "A Brief Survey of the Russian Historiography of Russian America of Recent Years". Pacific Historical Review. 79 (2): 265–278. doi:10.1525/phr.2010.79.2.265. ISSN 0030-8684.

- Herring, George Cyril (2008). From colony to superpower: U.S. foreign relations since 1776. The Oxford history of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507822-0.

- Kushner, Howard (1987). "The significance of the Alaska purchase to American expansion". In Starr, S. Frederick (ed.). Russia's American colony. A Special study of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 295–315. ISBN 978-0-8223-0688-7.

- Pierce, Richard A. (1990). Russian America: a biographical dictionary. Alaska history. Kingston, Ont. ; Fairbanks, Alaska: The Limestone Press. ISBN 978-0-919642-45-4.

- Holbo, Paul Sothe (1983). Tarnished expansion: The Alaska scandal, the press, and Congress, 1867-1871. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-380-5.

- Jensen, Ronald J. (1975). The Alaska purchase and Russian-American relations. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95376-2.

- Oberholtzer, Ellis (1917). A History of the United States since the Civil War. Vol. 1: 1865-68. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 700424822.

Primary sources

[edit]- Ahllund, Thomas (Fall 2006). "From the Memoirs of a Finnish Workman" (PDF). Alaska History. 21 (2). Translated by Hallamaa, Panu: 1–25. (Originally published in Finnish in Suomen Kuvalehti (editor-in-chief Julius Krohn) No. 15/1873 (1 August) – No. 19/1873 (1 October)); firsthand account of the transfer

- Seward, William Henry (1879). Alaska: Speech of William H. Seward at Sitka, August 12, 1869. Washington: J.J Chapman. hdl:loc.gdc/mtfgc.1003. LCCN 48031388. OCLC 9782079.

External links

[edit]- Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska and related resources at the Library of Congress

- Meeting of Frontiers, Library of Congress

- "Inside the Archivist's Office". American Artifacts. C-SPAN. December 26, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2017. Program featuring the purchase check cashed for gold at Riggs Bank (17:00 minute mark).

- Original Document of Check to Purchase Alaska Archived June 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (registration required)

- 1867 in Alaska

- 1867 in the Russian Empire

- 1867 in the United States

- 1867 treaties

- Aboriginal title in the United States

- Russian colonization of North America

- History of the American West

- History of United States expansionism

- March 1867 events in the United States

- Russian Empire–United States relations

- Treaties involving territorial changes

- Treaties of the Russian Empire

- Bilateral treaties of the United States

- Purchased territories

- Territorial evolution of Russia

- Bilateral treaties of Russia

- Presidency of Andrew Johnson

- Pre-statehood history of Alaska

- Alexander II of Russia