Setouchi Triennale

The Setouchi International Art Triennale is a contemporary art festival held every three years on several islands in the Seto Inland Sea of Japan and the coastal cities of Takamatsu and Tamano. The festival was inaugurated in 2010 with the aim of revitalizing the Seto Inland Sea area, which has suffered from depopulation in recent years, as well as long-standing environmental degradation from illegal industrial waste-dumping practices conducting during the 1970s following rapid industrialization in the area.[1][2]: 218

Initiated as a public-private partnership between the local prefectural and municipal governments and education publisher Benesse, the festival focuses on artistic endeavors that highlight local communities and environmental conditions, as well as site-specific installations that make use of existing spaces and ecological features. The festival has played a significant role in the growth and redevelopment of the region, serving as a leading example of the potentials of reinvestment in peripheral communities in decline after the explosive growth of major cities in Japan during the second half of the 20th century.

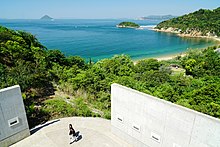

The Triennale lasts for eight months with three main sessions; the spring session runs from March to mid-April, the summer session runs from mid-July to early September, and the autumn session runs from October to early November.[3][4] While several of the museums and installations are permanent exhibitions, many of the smaller islands offer temporary exhibitions limited to a single session. Notable permanent fixtures include a series of concrete museums on Naoshima designed by architect Tadao Ando, as well as the Teshima Art Museum (2010), designed by Ryue Nishizawa featuring Rei Naito's Matrix, and the Art House Project (1998-present) on Naoshima, a series of commissions involving architects and artists who restore abandoned homes and other buildings and reinvent the spaces through artistic intervention.

History

[edit]Postwar industrial development and environmental degradation

[edit]The islands and cities that make up the triennale are located within the eastern portion of the Seto Inland Sea and the Setonaikai National Park, which was established as Japan's first national park in 1934.[2]: 218 The area was the site of major industrial development during the country's economic boom in the 1960s, and approximately one-third of the major factories built in Japan during this period were located in the Setonaikai region. As unchecked economic development continued to accelerate in the area, the islands in the sea became sites of illegal industrial waste dumping during the 1970s and 1980s, coming to a head in a large-scale national controversy in 1990 when it was discovered that 710,000 tons of industrial waste from scrapped cars had been illegally incinerated and buried on the island of Teshima.[5]: 326 [6]

Founding of Benesse Art Site project

[edit]In response to these environmental conditions, coupled with the challenges of aging and decreasing populations in the islands, Tetsuhiro Fukutake, founder of the Okayama-based Fukutake Publishing Co. (later Benesse), met with Chikatsugu Miyake, then-mayor of Naoshima in 1985 to discuss a plan for redeveloping the southern portion of the island as a cultural and educational facility for children.[7] Though Tetsuhiro passed away just months after the meeting, his son Soichiro took on the project, which resulted in the construction of the Naoshima International Camp in 1989. Designed by architect Tadao Ando, who helmed the designs of the major exhibition spaces across the islands, the campground would form the foundation of the Benesse Art Site, the collective title for the Benesse-initiated art projects on Naoshima, Teshima, and Inujima.[8] Frog and Cat, a large-scale public sculpture by Karel Appel was the first artwork to be installed on the island as part of the Benesse Art Site project in 1989.[9]

Under his vision that "economy is subordinate to culture," Fukutake continued to commission artists, curators, and architects and invest in cultural projects over the following decades. The Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum (now Benesse House), was established in 1992 to exhibit works from Fukutake's collection, followed by the Chichu Museum in 2004, which features site-specific installations by Walter de Maria and James Turrell, as well as four works from Claude Monet's Water Lilies series.[10]: 15 Both museums were designed by Tadao Ando, and feature his signature material of concrete while exhibiting a keen attentiveness towards environmental context, artistic content, and the affective potentials of space.

Outside of Naoshima, both Fukutake's private foundation and the Benesse company have constructed other institutions such as the Inujima Seirensho Art Museum, built on the remains of a former coal refinery in 2008, and the Teshima Art Museum, designed by Ryue Nishizawa in 2010 to house Rei Naito's Matrix, the only work on view at the site.[10]: 84

Establishment of Setouchi International Art Triennale

[edit]Beginning with the inception of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial in 2000, large-scale, recurring regional art festivals began to emerge across Japan as part of an effort to revitalized rural and depopulated areas, while expanding the presence and influence of art and cultural projects to areas beyond urban centers.[11]: 2374 Talks of organizing an art festival in the Setouchi region began in 2004, when the Kagawa prefectural government approached governor Takeki Manabe with the idea of establishing a program that drew from the prefecture's artistic and architectural ties to figures such as sculptor Isamu Noguchi, painter Gen'ichiro Inokuma, and architect Kenzo Tange.[12]: 465 [13] Infrastructural development in the area during the late 1980s and 1990s, notably the construction of the Great Seto Bridge and Kansai International Airport further supported the proposal to invest in the festival as a key driver of tourism in the area.[2]: 222

The local governments, along with Fukutake and the Benesse corporation, enlisted the aid of Fram Kitagawa, founder and director of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial, to produce a festival in the Setouchi region using the know-how and strategies acquired from his collaboration with local governments in Niigata.[10]: 92 The inaugural edition took place in 2010, coinciding with the opening of the Lee Ufan Museum, Teshima Art Museum, and the Inujima Art House Project.[10]: 92 While the executive committee initially estimated an attendance of 300,000 over the three months of the festival, the final count of visitors to exhibits and events held by the visitors came to 938,246, and the Takamatsu Branch of the Bank of Japan declared that the event had brought in economic benefits upwards of 11.1 billion yen.[10]: 93 The festival continues to be supported through a combination of funds from the Fukutake Foundation, the Fukutake family's own investments (estimated at around $250 million yen), the Benesse corporation, and governmental support. Soichiro Fukutake continues to lead the festival as well, along with his son, Hideaki.[6]

Over the past several iterations, the festival has expanded to encompass a greater period of time by being broken into spring, summer, and fall sessions, and the number of participating venues has increased from eight to fourteen. Since 2009, a volunteer nonprofit organization called the Koebi-tai (Little Shrimp Squad) has assisted with daily operations, visitor experience, as well as serving as liaisons between local residents and the festival.[12]: 465

The Fukutake family has stated that plans for the 2025 iteration include a new three-story, partially underground museum on Naoshima focused on Asian artists, as well as the renovation of a former junior high school on Teshima into a gallery space.[6]

Thematic orientation

[edit]Unlike other large-scale art festivals based around national pavilions and critical themes, the Setouchi Triennale tends towards focusing on local engagement, art's relationship to communities, landscapes, and traditions, and immersive visitor encounters that stress harmony between people, art, and environment.[2]: 221 As Hideaki Fukutake declared, "the philosophy underlying Naoshima is 'well-being.' We aim to introduce a rich, fulfilling lifestyle that has seemingly been forgotten by modem, urban society."[12]: 467 Such ideas often undergird the work of artists commissioned to produce site-specific, socially engaged artworks. For example, Motoyuki Shitamichi, whose practice involves immersion into the community and its local affairs, move to Naoshima with his family to distance himself from the bustle of major cities and pursue a long-term project on the industrial history of the island.[14]: 52–53

Reception and effects of festival

[edit]While the festival and the accompanying interstitial artistic interventions, craft and food fairs, and performances that take place both within and outside the "official" festival organized under the aegis of the Setouchi Triennale have brought a substantial amount of increased profit, tourism, and in some cases, population growth, not all communities included in the event have benefited equally from these interventions.[15]: 37 Shiu Hong Simon Tu notes the limited effect on population and development that the festival has had in Inujima, which is geographically more remote and has stricter regulations on new construction under Okayama City's City Planning Act, in comparison to other islands such as Teshima and Ogijima, both of which have reported an increased population of newcomers who are actively engaged in the continued survival of the communities.[15]: 35 Smaller communities such as Megijima and Inujima tend to have a greater percentage of older, retired residents, while larger islands such as Naoshima, Teshima, and Shodoshima tend to be richer in resources and are home to schools.[11]: 2379

Local residents vary in their receptiveness towards the festival, and the scattered presence of museums and other art destinations across the islands has resulted in certain communities, in particular Naoshima and Teshima, boasting substantially more festival-related development outcomes than islands with fewer and less high-profile installations, such as Shodoshima and Megijima.[12]: 2380–2381 The seasonal nature of the event and sharp surges and declines in customers also poses challenges for the construction of new businesses and the continued support of existing ones.[11]: 2380

The festival's focus on site-specific art also raises challenges regarding the transience of these engagements and the disparities in intellectual and cultural value they provide for tourists and local stakeholders, and artistic projects vary widely in their involvement with local residents and their interests.[14]: 58 Some critics have also called attention to the incongruence between Kitagawa and the organizers' insistence on shifting away from the culture of the metropolitan "art world" and the inclusion of works by internationally recognized figures such as Yayoi Kusama, Marina Abramović, and Olafur Eliasson.[16]: 147 As such, it is difficult to generalize the effects and role of the festival on the overall Setouchi region, as resident and tourist experiences, artistic approaches, and social contexts vary widely across the island and port city communities.

Participating Islands and Cities

[edit]The following 12 islands and two coastal cities participate in the Triennale.

| Place name | Sessions[17] | Summary/Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naoshima | Spring, summer, and autumn | Naoshima is home to the Benesse Art Site, and hosts the most museums of all participating islands. Permanent exhibits include the Chichu Art Museum,[18] Benesse House Museum, and the Art House Project. |  |

| Teshima | Spring, summer, and autumn | Permanent exhibitions include the Teshima Art Museum and the Teshima Yokoo House. |  |

| Megijima | Spring, summer, and autumn | In addition to permanent and temporary installations, several exhibitions at Megijima during the festival make use of the natural "Ogre's Caves" at the top of the island. |  |

| Ogijima | Spring, summer, and autumn | Numerous art projects from several iterations of the festival are installed on the island, including the Ogijima Pavilion (designed by Shigeru Ban with murals by Oscar Oiwa), Ogijima's Soul by Jaume Plensa, and Takotsuboru, a playground modeled after an octopus trap, by Team Ogi. |  |

| Shodoshima | Spring, summer, and autumn | The second-largest island in the inland sea known for its cultivation of olives and soy sauce breweries, Shodoshima features a number of installations including Gift of the Sun by Choi Jeong Hwa and Maze Town - Phantasmagoric Alleys by Me. |  |

| Oshima | Spring, summer, and autumn | Oshima is home to the Art for the Hospital Project, which uses art to capture the experiences of people who have recovered from Hansen's disease. |  |

| Inujima | Spring, summer, and autumn | The Inujima House Project is a number of independent exhibitions that are within walking distance of each other. |  |

| Shamijima | Spring only | Once an island, Shamijima has now been connected to the larger island of Shikoku. The art installations on Shamijima are on the part of the land that used to be an island. |  |

| Honjima | Spring only | Honjima is home to the historical district of Kasashima, and as such several of the exhibitions on this island have a historical theme. |  |

| Takamijima | Autumn only | The island's distinctive landscape is punctuated by residences built along tiered slopes and stone walls. Installations include Takamijima Project/Time falls by Kayako Nakashima, Terrace of Inland Sea by Masahito Nomura, and FLOW by Kendell Geers. |  |

| Awashima | Autumn only | Most of the art projects on Awashima are based around the Awashima Maritime Museum. |  |

| Ibukijima | Autumn only | The island features a number of architectural installations including House of Toilet by Daigo Ishii and The Dreaming of Things by KASA/Kovaleva and Sato Architect. |  |

| Takamatsu | Spring, summer, and autumn | Takamatsu is the main hub of the Setouchi Triennale, with many of the ferries to the islands departing from Takamatsu Port. It also holds several temporary exhibitions and installations of its own. |  |

| Uno Port (Tamano City) | Spring, summer, and autumn | Uno Port is another main gateway to the islands of the Inland Sea. It features several sculptures to celebrate the art festival. |  |

External links

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Setouchi Artfest". Setouchi Artfest. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d Chung, Simone Shu-Yeng (2019). "The social architecture of contemporary cultural festivals: Connecting people, the environment, and art in the Setouchi Triennale". In Browne, Jemma; Frost, Christian; Lucas, Ray (eds.). Architecture, Festival, and the City. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781138362345.

- ^ "Setouchi Artfest". Japan-guide. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ "Benesse Art Site". Benesse. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Fujikura, Manami (2011). "Japan's Efforts Against the Illegal Dumping of Industrial Waste: Efforts Against the Illegal Dumping of Industrial Waste". Environmental Policy and Governance. 21 (5). doi:10.1002/eet.581.

- ^ a b c Simms, James. "Japanese Tycoon Soichiro Fukutake Masters The Art Of The Turnaround". Forbes. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ "History of Benesse Art Site Naoshima | Benesse Art Site Naoshima". Benesse Art Site Naoshima. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ "Naoshima and the Beginnings of Art". ART SETOUCHI. 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ OECD, ed. (2014). "Case Study: Contemporary art and tourism on Setouchi Islands, Japan". Tourism and the creative economy. OECD studies on tourism. Paris: OECD. ISBN 978-92-64-20787-5.

- ^ a b c d e Tu, Shiu Hong Simon (2021). Revitalizing Japan’s Periphery through an International Art Festival: A Multi-Sited Ethnography of the Setouchi Triennale. PhD diss., The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- ^ a b c Qu, Meng; McCormick, A. D.; Funck, Caroline (2022-10-03). "Community resourcefulness and partnerships in rural tourism". Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 30 (10): 2371–2390. doi:10.1080/09669582.2020.1849233. ISSN 0966-9582.

- ^ a b c d Jack, James (2023). "The Art of Upcycling in the Seto Inland Sea". In Freedman, Alisa (ed.). Introducing Japanese Popular Culture (2nd ed.). London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-032-29808-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum Japan". www.isamunoguchi.or.jp. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ a b McCormick, A.D. (2022). "Augmenting Small-Island Heritage through Site-Specific Art: A View from Naoshima". Okinawan Journal of Island Studies. 3 (1): 41–60.

- ^ a b Tu, Shiu Hong Simon (2022). "Island Revitalization and the Setouchi Triennale: Ethnographic Reflection on Three Local Events". Okinawan Journal of Island Studies. 3 (1): 21–40.

- ^ Tagore-Erwin, Eimi (2018-09-17). "Contemporary Japanese art: between globalization and localization". Arts and the Market. 8 (2): 137–151. doi:10.1108/AAM-04-2017-0008. ISSN 2056-4945.

- ^ "Setouchi Artfest". Japan-guide. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ "Chichu Art Museum". Benesse. Retrieved 13 October 2016.