Sermons of Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift, as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin, produced many sermons during his tenure from 1713 to 1745.[1] Although Swift is better known today for his secular writings such as Gulliver's Travels, A Tale of a Tub or the Drapier's Letters, Swift was known in Dublin for his sermons that were delivered every fifth Sunday. Of these sermons, Swift wrote down 35, of which 12 have been preserved.[2] In his sermons Swift attempted to impart traditional Church of Ireland values to his listeners in a plain manner.[2]

Of the surviving twelve sermons, four have received serious consideration: "Doing Good", "False Witness", "Mutual Subjection" and "Testimony of Conscience".[3] These sermons deal with political matters and are used to give insight to Swift's political writing; the sermon "Doing Good" and its relationship with the Drapier's Letters is one such example. However, the audience at St. Patrick's Cathedral did not come to hear connections to political works, but to enjoy the well-known preacher and be "moved by his manners".[4]

Each sermon begins with a scriptural passage that reinforces the ideas that will be discussed in the sermon and each was preceded with the same opening prayer (which Swift also delivered).[2] The sermons are plainly written and apply a common-sense approach to contemporary moral issues in Dublin.[2] Swift patterned his sermons on the plain style of the Book of Common Prayer and the Church of Ireland Authorized Version of the Bible.[5][6]

Background

[edit]

As Dean of Saint Patrick's Cathedral, Jonathan Swift spent every fifth Sunday preaching from the pulpit.[7] Although many of his friends suggested that he should publish these sermons, Swift felt that he lacked the talent as a preacher to make his sermons worthy of publication.[8] Instead, Swift spent his time working more on political works, such as Drapier's Letters, and justified this by his lacking in religions areas.[9]

Members of St. Patrick's community would ask, "Pray, does the Doctor preach today?"[10] Swift's sermons had the reputation of being spoken "with an emphasis and fervor which everyone around him saw, and felt."[11] In response to such encouragement to preach, Swift was reported to say that he "could never rise higher than preaching pamphlets."[8] Swift's friend, Dr. John Arbuthnot, claimed, "I can never imagine any man can be uneasy, that has the opportunity of venting himself to a whole congregation once a week."[12] Regardless of what Swift thought of himself, the cathedral was always crowded during his sermons.[8]

Swift wrote out his sermons before preaching and marked his words to provide the correct pronunciation or to emphasise the word ironically.[13] He always practised reading his sermons, and, as Davis claims, "he would (in his own expression) pick up the lines, and cheat his people, by making them believe he had it all by heart."[14] However, he wanted to express the truth of his words and impart this truth in a down-to-earth manner that could be understood by his listeners.[13]

Swift believed that a preacher had to be understood, and states, "For a divine hath nothing to say to the wisest congregation of any parish in this kingdom, which he may not express in a manner to be understood by the meanest among them."[15] He elaborates further when he says, "The two principal branches of preaching, are first to tell the people what is their duty; and then to convince them that it is so."[16]

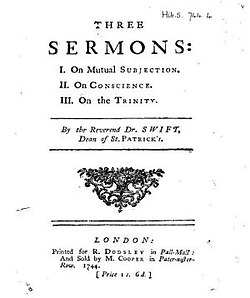

Shortly before his death, Swift gave the collection of 35 sermons to Dr. Thomas Sheridan, saying, "You may have them if you please; they maybe of use to you, they never were of any to me."[2] In 1744, George Faulkner, the Dublin publisher of Swift's 1735 Works, printed the sermons entitled "On Mutual Subjection," "On Conscience," and "On the Trinity."[2]

Surviving sermons

[edit]There are twelve surviving sermons that have been collected, and each sermon was introduced with a corresponding scriptural passage and the following prayer given by Swift:

Almighty and most merciful God! forgive us all our sins. Give us grace heartily to repent them, and to lead new lives. Graft in our hearts a true love and veneration for thy holy name and word. Make thy pastors burning and shining lights, able to convince gainsayers, and to save others and themselves. Bless this congregation here met together in thy name; grant them to hear and receive thy holy word, to the salvation of their own souls. Lastly, we desire to return thee praise and thanksgiving for all thy mercies bestowed upon us; but chiefly for the Fountain of them all, Jesus Christ our Lord, in whose name and words we further call upon thee, saying, 'Our Father,' &c."[2]

The order of the sermons is presented according to the 1763 Sermons of the Reverend Dr. Jonathan Swift "carefully corrected" edition, which published the first nine of the twelve known sermons.

On the Trinity

[edit]

Its introductory passage from scripture comes from First Epistle of John 5:7 – "For there are three that bear record in Heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost; and these Three are One."[17]

Swift relies on 1 Corinthians in this sermon, but unlike other uses by Swift of 1 Corinthians, his use of the epistle in "On the Trinity" describe man's inability to understand the complex workings of God.[18] Swift states "Behold I show you a mystery; we shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed."[19] The primarily use of this sermon is to describe the divine mysteries in a simple manner; Swift is not giving answers to the mysteries, but only explaining how Christians are to understand them.[20] Swift attempts to describe the ambiguous nature of the Trinity and how many should understand it when he says:

Therefore I shall again repeat the doctrine of the Trinity, as it is positively affirmed in Scripture: that God is there expressed in three different names, as Father, as Son, and as Holy Ghost: that each of these is God, and that there is but one God. But this union and distinction are a mystery utterly unknown to mankind.[19]

Although Swift constantly answers moral problems with common sense and reason, Swift believed that reason cannot be used when it comes to the divine mysteries.[21] Instead, faith is all that man needs and, as Swift claims:

This is enough for any good Christian to believe on this great article, without ever inquiring any farther: And, this can be contrary to no man's reason, although the knowledge of it is hid from him.[19]

On Mutual Subjection

[edit]

"On Mutual Subjection" was first given on 28 February 1718, and it was first printed in 1744.[22] Its introductory passage from scripture comes from First Epistle of Peter 5:5 – "--Yea, all of you be subject one to another."[23]

The sermon relies on scripture to emphasise the divine will in calling people to serve their fellow men, which is a common theme in Swift's sermons.[24] This calling, as Swift claims, is based on historical events that reinforce scripture and allow mankind to know of the divine will.[25] In particular, the development of the state and of the human body are parallel to each other, and England may soon be entering into a decline.[26] However, Swift emphasises that man is imperfect, and that sin is a symbol of this imperfectness.[27]

Swift summarises this message with the Parable of the Talents as he says:

God sent us into the world to obey His commands, by doing as much good as our abilities will reach, and as little evil as our many infirmities will permit. Some He hath only trusted with one talent, some with five, and some with ten. No man is without his talent; and he that is faithful or negligent in a little shall be rewarded or punished, as well as he that hath been so in a great deal."[24] To this John Boyle, Lord Orrery states, "A clearer style, or a discourse more properly adapted to a public audience, can scarce be framed. Every paragraph is simple, nervous, and intelligible. The threads of each argument are closely connected and logically pursued.[28]

Although the sermon deals primarily with subjection to higher powers, some of Swift's contemporaries viewed the sermon as political propaganda.[29] John Evans, Bishop of Meath, told the Archbishop of Canterbury that he heard "a strange sermon... It was somewhat like one of Montaigne's essays, making very free with all orders and degrees of men among us – lords, bishops, &c. men in power. The pretended subjects were pride and humiliation."[30] He later continued to claim that "in short, [Swift] is thought to be Tory... all over, which (here) is reckon'd by every honest man Jacobite."[30]

However, Evans may have overly emphasised a political interpretation of the sermon for his own political gain; the see of Derry had just opened and Evans wished to have his friend William Nicolson take the position.[29] Evans' political intrigue provoked Swift during an inspection of the clergy of Meath at Trim.[31] Swift, as vicar of Laracor spoke during a synod to defend himself, his sermons, and his politics, and instead of resolving the issue, only caused more dispute between the two.[32]

The emphasis on religious unity, also found in "On the Wisdom of this World", comes from Swift's understanding of St. Paul's treatment of religious dissension among the early Christians.[33] Paul's words, "that there should be no schism in the body", were important in the formation of this sermon, and served as part of Swift's encouragement to the people of Ireland to follow the same religion.[33][34]

On the Testimony of Conscience

[edit]

"On the Testimony of Conscience" was first printed in 1744.[35] Its introductory passage from scripture comes from 2 Corinthians 1:12 – "For our rejoicing is this, the testimony of our conscience."[36] Part of the sermon relied on discussing the nature of rewards and punishments to come in the afterlife.[37]

Religious dissension is the topic of this sermon and argues that dissenters do not want to embrace freedom, but instead exist only to destroy established Churches, especially the Church of Ireland.[38] In the sermon, Swift conflates all dissenters with the Whig political party, and they are "those very persons, who under a pretence of a public spirit and tenderness towards their Christian brethrene, are so jealous for such a liberty of conscience as this, are of all others the least tender to those who differ from them in the smallest point relating to government."[39] To Swift, tolerating dissent is the same as tolerating blasphemy.[40]

The work is filled with innuendo towards the rule of King George and his toleration of Whigs and dissenters as tyrannical; Swift claims that a leader who tolerates religious dissenters was like a "heathen Emperor, who said, if the gods were offended, it was their own concern, and they were able to vindicate themselves."[39] To Swift, such leaders would eventually lose power, because God's divine will manifests itself in historic outcomes.[25]

In particular, Swift relies on a quote from Tiberius, as reported by Tacitus, to describe the "heathen" thoughts.[36] Swift relied on Tiberius' quote when mocking leaders who would undermine religious unity or those who were completely opposed to Christianity, such as in An Argument against Abolishing Christianity.[35] Swift believed in the need for citizens to be required to follow Anglican religious practices and to honor the king as head of the Church, and a king who would who did not believe in the same could be nothing less than pagan.[41]

Part of the sermon is dedicated to comparing the actions of the Irish church, in its struggle against religious dissenters and political uncertainty, with that of the primitive church.[42] In particular, Swift claims, "For a man's Conscience can go no higher than his Knowledge; and therefore until he has thoroughly examined by Scripture, and the practice of the ancient Church, whether those points are blamable or no, his Conscience cannot possibly direct him to condemn them."[39] However, Swift does not believe that experience alone could make one capable of understanding virtue or being capable of teaching virtue.[43]

Regardless of the innuendo about Roman religious tyranny or comparisons to early Christian history, the sermon is given, as Ehrenpreis claims, with an "air of simplicity, frankness, common sense, and spontaneity" that "disarms the listener."[40] This sermon, in its plain language, is able to convey Swift's message in a manner that could be seen as contradictory if it was embellished by history, allusions, or complex reasoning.[44]

On Brotherly Love

[edit]

"On Brotherly Love" was given on 29 November 1717.[45] Its introductory passage from scripture comes from Hebrews 8:1 – "Let brotherly love continue."[46]

Although Swift is preaching on "brotherly love", he dwells on the topic of true religion and political dissent, and he uses his sermon to preach against those who are politically and religiously different from himself and the members of St. Patrick's community.[45] He introduces this claim when he says:

This nation of ours hath, for an hundred years past, been infested by two enemies, the Papists and fanatics, who, each in their turns, filled it with blood and slaughter, and, for a time, destroyed both the Church and government. The memory of these events hath put all true Protestants equally upon their guard against both these adversaries, who, by consequence, do equally hate us. The fanatics revile us, as too nearly approaching to Popery; and the Papists condemn us, as bordering too much on fanaticism. The Papists, God be praised, are, by the wisdom of our laws, put out of all visible possibility of hurting us; besides, their religion is so generally abhorred, that they have no advocates or abettors among Protestants to assist them. But the fanatics are to be considered in another light; they have had of late years the power, the luck, or the cunning, to divide us among ourselves;[45]

Throughout this sermon, Swift emphasises that history is connected to the divine will throughout this sermon to criticise those who dissent.[25] For example:

And others again, whom God had formed with mild and gentle dispositions, think it necessary to put a force upon their own tempers, by acting a noisy, violent, malicious part, as a means to be distinguished. Thus hath party got the better of the very genius and constitution of our people; so that whoever reads the character of the English in former ages, will hardly believe their present posterity to be of the same nation or climate.[45]

This work was printed and distributed as a solo tract in 1754.[45]

On the Difficulty of Knowing One's Self

[edit]

Although "On the Difficulty of Knowing One's Self" was printed in 1745 along with some of Swift's other sermons, its authorship is not completely established, since the original printing of the work came with the following disclaimer:

The manuscript title page of the following sermon being lost, and no memorandum writ upon it, as there were upon the others, when and where it was preached, made the editor doubtful whether he should print it as the Dean's, or not. But its being found amongst the same papers; and the hand, though writ somewhat better, bearing a great similitude to the Dean's, made him willing to lay it before the public, that they might judge whether the style and manner also does not render it still more probable to be his."[47]

The sermon deals with the issues of understanding one's self and how to act towards others in a Christian manner. Its introductory passage from scripture comes from 2 Kings 8:13 -"And Hazael said, But what, is thy servant a dog, that he should do this great thing?" and the sermon concludes with the golden rule:

let him keep an eye upon that one great comprehensive rule of Christian duty, on which hangs, not only the law and the prophets, but the very life and spirit of the Gospel too: "Whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so unto them." Which rule, that we may all duly observe, by throwing aside all scandal and detraction, all spite and rancour, all rudeness and contempt, all rage and violence, and whatever tends to make conversation and commerce either uneasy, or troublesome, may the God of peace grant for Jesus Christ his sake, &c.[48]

Swift relies on Gospel of Matthew in this sermon (Swift quotes from the Sermon on the Mount, Matthew 7:12) instead of the other Gospels;[48] this is standard practice for Swift, because the Gospel features a simple, non-controversial history that complements Swift's religious views.[49]

On False Witness

[edit]

"On False Witness" was given in 1715.[50] Its introductory passage from scripture comes from Exodus 20:16 – "Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour."[51]

This sermon deals primarily with the topic of informers; an informer had produced evidence that Swift was breaching King George's order against preachers involving themselves in political matters.[52] Swift, as a Tory propagandist, had been sent a package from another Tory; the package was intercepted by a customs officer and it put Swift into hot water from the Whig politicians in power at the time.[53] The sermon was used to attack those who "catch up an accidental word" and misstate situations to hurt others.[54] Swift alludes to such people when he says:

Such witnesses are those who cannot hear an idle intemperate expression, but they must immediately run to the magistrate to inform; or perhaps wrangling in their cups over night, when they were not able to speak or apprehend three words of common sense, will pretend to remember everything the next morning, and think themselves very properly qualified to be accusers of their brethren. God be thanked, the throne of our King is too firmly settled to be shaken by the folly and rashness of every sottish companion.[51]

Half of the sermon is used to criticise the Whigs and their political activities.[55] The other half is devoted to condemning Tories who betray other Tories as criminals, to gain favour with the Whigs.[55] The Whigs are characterised as the persecutors of the early Christians, and betraying Tories are characterised as apostates.[55]

Although King George I had issued a royal edict against speaking about political informers in regards to potential Jacobite rebellion, Swift felt that the issue was necessary to not only defend himself, but to defend all politically oppressed people.[56] Immediately after the sermon, Prime Minister Robert Walpole used his power to form "The Committee of Secrecy" and deemed that Swift's allies, Lord Bolingbroke, Lord Oxford, Lord Strafford, and Duke Ormonde would be sent to the Tower of London.[57] However, Lord Bolingbroke and Duke Ormonde fled to France, and Oxford was taken to the Tower.[57] This placed Swift at a political disadvantage, but he was mostly ignored.[58]

On the Poor Man's Contentment

[edit]

Its introductory passage from scripture comes from Epistle to the Philippians 4:11 – "I have learned, in whatsoever state I am, therewith to be content".[59]

In this sermon, Swift was worried about how guilt affects mankind or how the lack of guilt is a sign of mankind's problems:[37] "the Shortness of his Life; his Dread of a future State, with his Carelessness to prepare for it."[59] He explains this:

And, it is a mistake to think, that the most hardened sinner, who oweth his possessions or titles to any such wicked arts of thieving, can have true peace of mind, under the reproaches of a guilty conscience, and amid the cries of ruined widows and orphans.[59]

Swift is trying to convince his listeners that they needed to contemplate their life and their death, and that they need to understand the rewards and punishments that await them in the afterlife.[37] He emphasises this point when he explains the importance of meekness and modesty:

Since our blessed Lord, instead of a rich and honourable station in this world, was pleased to choose his lot among men of the lower condition; let not those, on whom the bounty of Providence hath bestowed wealth and honours, despise the men who are placed in a humble and inferior station; but rather, with their utmost power, by their countenance, by their protection, by just payment of their honest labour, encourage their daily endeavours for the support of themselves and their families. On the other hand, let the poor labour to provide things honest in the sight of all men; and so, with diligence in their several employments, live soberly, righteously, and godlily in this present world, that they may obtain that glorious reward promised in the Gospel to the poor, I mean the kingdom of Heaven.[59]

But it is not just knowing your own fate in the afterlife, but also recognising the good in others and respecting that good.[37]

On the Wretched Condition of Ireland

[edit]

The sermon is properly titled "A Sermon on the Wretched Conditions of Ireland".[60] Its introductory passage from scripture comes from Psalms 144: 14–15 – "That there be no complaining in our streets. Happy is the people that is in such a case."[61]

This sermon has been characterised as being particularly grounded in politics, and Swift sums up many of the political issues that he had previously addressed in pamphlets and essays.[60] The solution to fixing the misery of the Irish people is:

to found a school in every parish of the kingdom, for teaching the meaner and poorer sort of children to speak and read the English tongue, and to provide a reasonable maintenance for the teachers. This would, in time, abolish that part of barbarity and ignorance, for which our natives are so despised by all foreigners: this would bring them to think and act according to the rules of reason, by which a spirit of industry, and thrift, and honesty would be introduced among them. And, indeed, considering how small a tax would suffice for such a work, it is a public scandal that such a thing should never have been endeavoured, or, perhaps, so much as thought on.[61]

However, lack of education is not the only problem for Ireland; many problems come from the vices of the Irish citizenry.[62] These vices span the way of dress to the inactivity of the common person.[62] To correct the problems of Ireland, Swift emphasises the need for his people to contribute to various charities, and concludes:

I might here, if the time would permit, offer many arguments to persuade to works of charity; but you hear them so often from the pulpit, that I am willing to hope you may not now want them. Besides, my present design was only to shew where your alms would be best bestowed, to the honour of God, your own ease and advantage, the service of your country, and the benefit of the poor. I desire you will all weigh and consider what I have spoken, and, according to your several stations and abilities, endeavour to put it in practice;[61]

Some critics have seen Swift as hopeless in regards to actual change for Ireland.[63] The rich could never change from their absentee landlord mentality that has stripped Ireland of its economic independence, and that is why Swift spends the majority of his sermon discussing the poor.[63] Swift proposes a remedy of sorts that would help the poor; they should be educated and the free travel of beggars should be restricted.[63] These ideas were intended to limit the amount that the poor consumed in society, which, combined with a proposal for the poor to act more virtuously, should correct many of the problems that plague Ireland, but these ideas were never put into effect.[64]

On Sleeping in Church

[edit]

Its introductory passage from scripture comes from Acts of the Apostles 20:9 – "And there sat in a window a certain young man, named Eutychus, being fallen into a deep sleep; and as Paul was long preaching, he sunk down with sleep, and fell down from the third loft, and was taken up dead."[65]

In this sermon, Swift criticises a "decay" in preaching that has led to people falling asleep in church.[66] Throughout the Sermon, Swift constantly relies on the Parable of the Sower.[49] Swift emphasises the wording of St. Matthew when he says, "whose Hearts are waxed gross, whose Ears are dulled of hearing, and whose eyes are closed," and he uses "eyes are closed" to connect back to those sleeping in Church.[49][65]

People not attending Church is another problem addressed in the sermon. Swift states:

Many men come to church to save or gain a reputation; or because they will not be singular, but comply with an established custom; yet, all the while, they are loaded with the guilt of old rooted sins. These men can expect to hear of nothing but terrors and threatenings, their sins laid open in true colours, and eternal misery the reward of them; therefore, no wonder they stop their ears, and divert their thoughts, and seek any amusement rather than stir the hell within them."[65]

He describes these people as:

Men whose minds are much enslaved to earthly affairs all the week, cannot disengage or break the chain of their thoughts so suddenly, as to apply to a discourse that is wholly foreign to what they have most at heart."[65]

The people are unwilling to be confronted by the results of their actions in the afterlife, and it is this problem that Swift wants to prevent.[27]

On the Wisdom of this World

[edit]"On the Wisdom of this World" was originally titled "A Sermon upon the Excellence of Christianity in Opposition to Heathen Philosophy" in the 1765 edition of Swift's Works.[67] Its introductory passage from scripture comes from I Corinthians 3:19 – "The wisdom of this world is foolishness with God."[67] This sermon emphasises the nature of rewards and punishments, and how such aspects of Christianity had been lacking in the classical philosophies.[37]

Except for The Gospel of St. Matthew, Swift relied on I Corinthians more than any other Biblical book. I Corinthians was a favourite work for Swift to rely on, because the epistle emphasises how to act as a proper Christian and how to conform to united principles.[68] Although the Anglican mass emphasises the Epistle to the Romans,[68] Swift relied on Corinthians in order to combat religious schismatic tendencies in a similar manner to his criticism of dissenters in "On Mutual Subjection".[69]

However, a second aspect of I Corinthians also enters into the sermon; Swift relies on it to promote the idea that reason can be used to comprehend the world, but "excellency of speech" is false when it comes to knowledge about the divine.[70] To this, Swift said, "we must either believe what God directly commandeth us in Holy Scripture, or we must wholly reject the Scripture, and the Christian Religion which we pretend to confess".[67]

On Doing Good

[edit]

"On Doing Good: A Sermon on the Occasion of Wood's Project" was given in 1724.[71] Its introductory passage from scripture comes from Galatians 6:10 -"As we have therefore opportunity, let us do good unto all men."[72]

It is unsure when the sermon was actually given, but some critics suggest it was read immediately following the publication of Swift's Letter to the Whole People of Ireland[73] while others place it in October 1724.[74]

According to Sophie Smith, Swift's "On Doing Good" sermon is about a patriotic ideal that is "higher than most ideals published in text-books on that subject."[75] "On Doing Good" calls the people to act on a higher level of ethics, which Smith describes as "Baconian".[75]

Smith claims that Swift discusses this ideal when he says:

Under the title of our neighbour, there is yet a duty of a more large, extensive nature incumbent on us – our love to our neighbour is his public capacity, as he is a member of that greatly body, the Commonwealth, under the same government with ourselves, and this is usually called love of the public, and is a duty to which we are more strictly obliged than even that of loving ourselves, because wherein ourselves are also contained – as well as all our neighbours – is one great body.[72][75]

And:

But here I would not be misunderstood. By the love of our country, I do not mean loyalty to our King, for that is a duty of another nature, and a man may be very loyal, in the common sense of the word, without one grain of public good in his heart. Witness this very kingdom we live in. I verily believe, that since the beginning of the world, no nation upon earth ever shewed (all circumstances considered), such high constant marks of loyalty in all their action and behaviour as we have done; and at the same time, no people ever appeared more utterly void of what is called public spirit ... therefore, I shall think my time not ill-spent if I can persuade most and all of you who hear me, to shew the love you have for your country by endeavouring in your several situations to do all the public good you can. For I am certain persuaded that all our misfortunes arise from no other original cause than that general disregard among us to the public welfare.[72][76]

Swift felt that it was his duty as Dean to raise the "Irish self-esteem" to liberate the Irish from English economic oppression.[77]

Beyond basic "self-esteem" issues, Swift used the sermon to reinforce the moral arguments incorporated into the Drapier's Letters with religious doctrine and biblical authority.[78] One image, that of Nineveh and Nimrod, appears in both the sermon and the letters.[79] Nimrod represents Ireland's desire to coin its own currency and he is a warning to the English that Ireland will not tolerate England's despotic control.[79] Furthermore, the use of "Nineveh" reinforces Swift's claim that Ireland is under "God's special providence".[79]

Because of the correlation between this sermon and the Drapier's Letters, Swift remarked, "I never preached but twice in my life; and then they were not sermons, but pamphlets.... They were against Wood's halfpence."[80] Even if this sermon was more of a pamphlet, Swift emphasises the divine will and how it guides history.[25] Like the Drapier's Letters, "On Doing Good" caused the Irish people to respect Swift as a hero and a patriot.[81]

On the Martyrdom of King Charles I

[edit]"On the Martyrdom of King Charles I" was given on 30 January 1725.[82] Its introductory passage from scripture comes from Genesis 49:5–7 –

Simeon and Levi are brethren; instruments of cruelty are in their habitations./ O my soul, come not thou into their secret; unto their assembly, mine honour, be not thou united: for in their anger they slew a man, and in their self-will they digged down a wall./ Cursed be their anger, for it was fierce; and their wrath, for it was cruel. I will divide them in Jacob, and scatter them in Israel.[82]

The letter served two purposes: the first was to honour the martyrdom of King Charles I and the second was to criticise dissenters against the Church of Ireland.[82] Swift emphasises both when he says:

I know very well, that the Church hath been often censured for keeping holy this day of humiliation, in memory of that excellent king and blessed martyr, Charles I, who rather chose to die on a scaffold, than betray the religion and liberties of his people, wherewith God and the laws had entrusted him."[82]

To Swift, the dissent that led to King Charles I's martyrdom defied God's divine will.[25]

Swift concludes his sermon with:

On the other side, some look upon kings as answerable for every mistake or omission in government, and bound to comply with the most unreasonable demands of an unquiet faction; which was the case of those who persecuted the blessed Martyr of this day from his throne to the scaffold. Between these two extremes, it is easy, from what hath been said, to choose a middle; to be good and loyal subjects, yet, according to your power, faithful assertors of your religion and liberties; to avoid all broachers and preachers of newfangled doctrines in the Church; to be strict observers of the laws, which cannot be justly taken from you without your own consent: In short, 'to obey God and the King, and meddle not with those who are given to change.'[82]

Reception

[edit]Lord Orrery favourably described that some of Swift's sermons were more properly moral or political essays.[28] Lord Orrery prefaced the 1763 edition of The Sermons with:

These Sermons are curious; and curious for such reason as would make other works despicable. They were written in a careless hurrying manner; and were the offspring of necessity, not of choice: so that one will see the original force of the Dean's genius more in these compositions, that were the legitimate sons of duty, than in other pieces that were natural sons of love.

The Bishop of Meath, John Evans, agreed with Lord Orrery's critique of the sermons as political works, and he compared a sermon to the writing of Montaigne.[30]

Sir Walter Scott wrote:

The Sermons of Swift have none of that thunder which appals, or that resistless and winning softness which melts, the hearts of an audience. He can never have enjoyed the triumph of uniting hundreds in one ardent sentiment of love, of terror, or of devotion. His reasoning, however powerful, and indeed unanswerable, convinces the understanding, but is never addressed to the heart; and, indeed, from his instructions to a young clergyman, he seems hardly to have considered pathos as a legitimate ingredient in an English sermon. Occasionally, too, Swift's misanthropic habits break out even from the pulpit; nor is he altogether able to suppress his disdain of those fellow mortals, on whose behalf was accomplished the great work of redemption. With such unamiable feelings towards his hearers, the preacher might indeed command their respect, but could never excite their sympathy. It may be feared that his Sermons were less popular from another cause, imputable more to the congregation than to the pastor. Swift spared not the vice of rich or poor; and, disdaining to amuse the imaginations of his audience with discussion of dark points of divinity, or warm them by a flow of sentimental devotion, he rushes at once to the point of moral depravity, and upbraids them with their favourite and predominant vices in a tone of stern reproof, bordering upon reproach. In short, he tears the bandages from their wounds, like the hasty surgeon of a crowded hospital, and applies the incision knife and caustic with salutary, but rough and untamed severity. But, alas! the mind must be already victorious over the worst of its evil propensities, that can profit by this harsh medicine. There is a principle of opposition in our nature, which mans itself with obstinacy even against avowed truth, when it approaches our feelings in a harsh and insulting manner. And Swift was probably sensible, that his discourses, owing to these various causes, did not produce the powerful effects most grateful to the feelings of the preacher, because they reflect back to him those of the audience.

But although the Sermons of Swift are deficient in eloquence, and were lightly esteemed by their author, they must not be undervalued by the modern reader. They exhibit, in an eminent degree, that powerful grasp of intellect which distinguished the author above all his contemporaries. In no religious discourses can be found more sound good sense, more happy and forcible views of the immediate subject. The reasoning is not only irresistible, but managed in a mode so simple and clear, that its force is obvious to the most ordinary capacity. Upon all subjects of morality, the preacher maintains the character of a rigid and inflexible monitor; neither admitting apology for that which is wrong, nor softening the difficulty of adhering to that which is right; a stern stoicism of doctrine, that may fail in finding many converts, but leads to excellence in the few manly minds who dare to embrace it. In treating the doctrinal points of belief, (as in his Sermon upon the Trinity,) Swift systematically refuses to quit the high and pre-eminent ground which the defender of Christianity is entitled to occupy, or to submit to the test of human reason, mysteries which are placed, by their very nature, far beyond our finite capacities. Swift considered, that, in religion, as in profane science, there must be certain ultimate laws which are to be received as fundamental truths, although we are incapable of defining or analysing their nature; and he censures those divines, who, in presumptuous confidence of their own logical powers, enter into controversy upon such mysteries of faith, without considering that they give thereby the most undue advantage to the infidel. Our author wisely and consistently declared reason an incompetent judge of doctrines, of which God had declared the fact, concealing from man the manner. He contended, that he who, upon the whole, receives the Christian religion as of divine inspiration, must be contented to depend upon God's truth, and his holy word, and receive with humble faith the mysteries which are too high for comprehension. Above all, Swift points out, with his usual forcible precision, the mischievous tendency of those investigations which, while they assail one fundamental doctrine of the Christian religion, shake and endanger the whole fabric, destroy the settled faith of thousands, pervert and mislead the genius of the learned and acute, destroy and confound the religious principles of the simple and ignorant.[2]

Scott's contemporary Edmund Burke said concerning Swift's sermon on "Doing Good,":

The pieces relating to Ireland are those of a public nature; in which the Dean appears, as usual, in the best light, because they do honour to his heart as well as to his head; furnishing some additional proofs, that, though he was very free in his abuse of the inhabitants of that country, as well natives as foreigners, he had their interest sincerely at heart, and perfectly understood it. His sermon upon Doing Good, though peculiarly adapted to Ireland and Wood's designs upon it, contains perhaps the best motives to patriotism that were ever delivered within so small a compass.[83]

In Swift's later works

[edit]- Aspects of "On False Witness" are used by Gulliver in his attack against informers.[84]

- "On Doing Good" is alluded to in the Drapier's fifth letter.[85]

- "On Doing Good" is mentioned in the Drapier's sixth letter when he states, "I did very lately, as I thought it my duty, preach to the people under my inspection, upon the subject of Mr. Wood's coin; and although I never heard that my sermon gave the least offence, as I am sure none was intended; yet, if it were now printed and published, I cannot say, I would insure it from the hands of the common hangman; or my own person from those of a messenger."[86]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mason

- ^ a b c d e f g h Prose Works ed. Scott Intro

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 1041

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 175

- ^ Prose Works ed. Davis pp. 14–15

- ^ Daw, Carl "Favorite Books" p. 201

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 74

- ^ a b c Lyon p. 75

- ^ Delany p. 38

- ^ Delany pp. 41–42

- ^ Delany p. 43

- ^ Correspondence p. 144

- ^ a b Ehrenpreis p. 76

- ^ Clifford pp. 147–158

- ^ Prose Works Vol IX. p. 66

- ^ Prose Works Vol IX. p. 70

- ^ "On the Trinity" Intro Note

- ^ Daw "Favorite Books" p. 205

- ^ a b c "On the Trinity" Sermon

- ^ Landa, Louis A. "Swift, the Mysteries, and Deism," Studies in English, 1944. pp. 239–256

- ^ Harth, Philip. Swift and Anglican Rationalism: The Religious Background of A Tale of a Tub. Chicago 1961 Intro Notes.

- ^ Daw, Carl P. "Swift's 'Strange Sermon'" HLQ 38 (1975), pp. 225–236

- ^ "On Mutual Subjection" Intro Note

- ^ a b "On Mutual Subjection" Sermon

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, James William. "Swift's Historical Outlook". The Journal of British Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2 (May 1965), p. 59

- ^ Johnson p. 73

- ^ a b Barroll, J. Leeds. "Gulliver and the Struldbruggs". PMLA, Vol. 73, No. 1 (March 1958) p. 46

- ^ a b Boyle, John. Remarks on the Life and Writing of Dr. Jonathan Swift. 1752. pp. 289–296

- ^ a b Ehrenpreis p. 53

- ^ a b c Landa, Louis A. Swift and the Church of Ireland. Oxford 1954. p. 182

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 54

- ^ Delaney p. 217

- ^ a b Daw "Favorite Books" p. 204

- ^ Prose Works IX p. 143

- ^ a b Swift, Jonathan. Major Works. ed. Angus Ross and David Woolley. Oxford World Classics, 1984. p. 662

- ^ a b "On the Testimony of Conscience" Intro Note

- ^ a b c d e Barroll p. 45

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 80

- ^ a b c "On the Testimony of Conscious" Sermon

- ^ a b Ehrenpreis p. 81

- ^ Major Works p. 642

- ^ Daw "Favorite Books" p. 208

- ^ Barroll p. 49

- ^ Price, Martin. Swift's Rhetorical Art. New Haven 1953. pp. 16–22

- ^ a b c d e Prose Works IV. "On Brotherly Love" Intro Note

- ^ "On Brotherly Love" Intro Note

- ^ Prose Works IV. "On the Difficulty of Knowing One's Self" Intro Note

- ^ a b "On the Difficulty of Knowing One's Self" Sermon

- ^ a b c Daw "Favorite Books" p. 211

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 972

- ^ a b Prose Works IV. "On False Witness" Sermon

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 9

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 14

- ^ Prose Works IX p. 183

- ^ a b c Ehrenpreis p. 17

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 16;17

- ^ a b Ehrenpreis p. 18

- ^ Ehrenpreis pp. 19–20

- ^ a b c d "On the Poor Man's Contentment" Sermon

- ^ a b "On the Wretched Condition of Ireland" Intro Note

- ^ a b c "On the Wretched Condition of Ireland" Sermon

- ^ a b Johnson p. 70

- ^ a b c Mahony p. 522

- ^ Mahony p. 523

- ^ a b c d "On Sleeping in Church" Sermon

- ^ "On Sleeping in Church" Intro Note

- ^ a b c Prose Works IV. "On the Wisdom of this World" sermon

- ^ a b Daw "Favorite Books" pp. 202–203

- ^ Daw "Favorite Books" p. 203

- ^ Daw "Favorite Books" p. 206

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 1015

- ^ a b c "On Doing Good" Sermon

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 246 footnote 4

- ^ Prose Works IX pp. 134–136

- ^ a b c Smith, Sophie. Dean Swift. Methuen & Co. 1910 p. 279

- ^ Smith pp. 281–282

- ^ Smith p. 282

- ^ Ehrenpreis p. 246

- ^ a b c Eilon, Daniel. "Swift Burning the Library of Babel". The Modern Language Review, Vol. 80, No. 2 (April 1985), p. 274

- ^ Pilkington, Laetitia. Memoirs of Mrs L. Pilkington. Vol. 1 1748. p. 56

- ^ Smith p. 283

- ^ a b c d e "On the Martyrdom of King Charles I" Sermon

- ^ Burke, Edmund. Writings and Speeches. World's Classics ed. Oxford, 1906.

- ^ Prose Works XI p. 191

- ^ Prose Works Vol. VI. Letter 5

- ^ Prose Works IV. "On Doing Good" Sermon Intro Note

References

[edit]- Clifford, James L. & Landa-Clifford, Louis A. "The Manuscript of Swift's Sermon on Brotherly Love". Pope and His Contemporaries: Essays Presented to George Sherburn. Oxford, 1949.

- Daw, Carl P (1980). "Swift's Favorite Books of the Bible". The Huntington Library Quarterly. 43 (3, Summer 1980): 114–124. doi:10.2307/3817463. JSTOR 3817463.

- Delany, Patrick. Observations upon Lord Orrery's Remarks on... Swift. Dublin, 1754. ISBN 0-674-85835-2.

- Ehrenpreis, Irvin. Jonathan Swift: Volume III. Harvard University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-674-85835-2.

- Ferguson, Oliver W. Jonathan Swift and Ireland. University of Illinois Press, 1962.

- Johnson, James William (May 1965). "Swift's Historical Outlook". The Journal of British Studies. 4 (2): 52–77. doi:10.1086/385500. S2CID 145771237.

- Lyon, John (1755). The Life of Jonathan Swift. Forster Collection.

- Mason, William Monck. History of St. Patrick's Cathedral. Dublin, 1820.

- Mahony, Robert. "Protestant Dependence and Consumption in Swift's Writings". Gulliver's Travels and Other Writings: Houghton Mifflin Company. 2004. pp. 501–524.

- Smith, Sophie. Dean Swift. London: Methuen & Co., 1910.

- Swift, Jonathan. Correspondence. Vol. IV. Ed. Harold Williams. Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1965.

- Swift, Jonathan. The Prose Works of Jonathan Swift, Vol. IV; Writings on Religion and the Church Vol. 2. ed. Temple Scott. London: George Bell and Sons. 1903.

- Swift, Jonathan. The Prose Works of Jonathan Swift Vol. IV. ed. Herbert Davis, Oxford University Press. 1939.

External links

[edit]