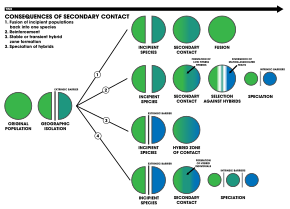

Secondary contact

1. An extrinsic barrier separates a species population into two but they come into contact before reproductive isolation is sufficient to result in speciation. The two populations fuse back into one species

2. Speciation by reinforcement

3. Two separated populations stay genetically distinct while hybrid swarms form in the zone of contact

4. Genome recombination results in speciation of the two populations, with an additional hybrid species. All three species are separated by intrinsic reproductive barriers[1]

Secondary contact is the process in which two allopatrically distributed populations of a species are geographically reunited. This contact allows for the potential for the exchange of genes, dependent on how reproductively isolated the two populations have become. There are several primary outcomes of secondary contact: extinction of one species, fusion of the two populations back into one, reinforcement, the formation of a hybrid zone, and the formation of a new species through hybrid speciation.[1]

Extinction

[edit]One of the two populations may go extinct due to competitive exclusion after secondary contact. This tends to happen when the two populations have strong reproductive isolation and significant overlap in their niche. A possible way to prevent extinction is if there is an advantage to being rare. For example, sexual imprinting and male-male competition[clarification needed] may prevent extinction. [2]

The population that goes extinct may leave behind some of its genes in the surviving population if they hybridize. For example, the secondary contact between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, as well as the Denisovans, left traces of their genes in modern human. However, if hybridization is so common that the resulting population received significant amount of genetic contribution from both populations, the result should be considered a fusion.

Fusion

[edit]The two populations may fuse back into one population. This tends to occur when there is little to no reproductive isolation between the two. During the process of fusion, a hybrid zone may occur. This is sometimes called introgressive hybridization or reverse speciation. Concerns have been raised that the homogenizing of the environment may contribute to more and more fusion, leading to the loss of biodiversity. [3]

Hybrid zones

[edit]A hybrid zone may appear during secondary contact, meaning there would be an area where the two populations cohabitate and produce hybrids, often arranged in a cline. The width of the zone may vary from tens of meters to several hundred kilometers. A hybrid zone may be stable, or it may not. Some shift in one direction, which may eventually lead to the extinction of the receding population. Some expand over time until the two populations fuse. [4]

Reinforcement may occur in hybrid zones.

Hybrid zones are important study systems for speciation. [4]

Reinforcement

[edit]Reinforcement is the evolution towards increased reproductive isolation due to selection against hybridization. This occurs when the populations already have some reproductive isolation, but still hybridize to some extent. Because hybridization is costly (e.g. giving birth and raising a weak offspring), natural selection favors strong isolation mechanisms that can avoid such outcome, such as assortative mating.[5] Evidence for speciation by reinforcement has been accumulating since the 1990s.

Hybrid speciation

[edit]Occasionally, the hybrids may be able to survive and reproduce, but not backcross with either of the two parental lineages, thus becoming a new species. This often occur in plants through polyploidy, including in many important food crops. [6]

Occasionally, the hybrids may lead to the extinction of one or both parental lineages.

References

[edit]- ^ a b John A. Hvala and Troy E. Wood (2012). "Speciation: Introduction". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0001709.pub3. ISBN 978-0470016176.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Yang, Y., Servedio, M. R., & Richards-Zawacki, C. L. (2019). Imprinting sets the stage for speciation. Nature, 574(7776), 99-102.

- ^ Seehausen, O. (2006). Conservation: losing biodiversity by reverse speciation. Current Biology, 16(9), R334-R337.

- ^ a b N. H. Barton & G. M. Hewitt (1985). "Analysis of hybrid zones". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 16: 113–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.16.110185.000553.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, M. (2000). Reinforcement and divergence under assortative mating. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 267(1453), 1649-1655.

- ^ Otto, S.; Witton, P. J. (2000). "Polyploid incidence and evolution" (PDF). Annual Review of Genetics. 34: 401–437. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.323.1059. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.401. PMID 11092833.