Browser wars

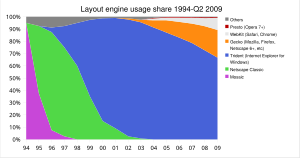

A browser war is a competition for dominance in the usage share of web browsers. The "first browser war" (1995–2001) consisted of Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator,[2] and the "second browser war" (2004-2017) between Internet Explorer, Firefox, and Google Chrome.[3]

With the introduction of HTML5 and CSS 3, a new generation of browser wars began, this time adding extensive client-side scripting to the World Wide Web (WWW), and the more widespread use of smartphones and other mobile devices for browsing the web. These changes have ensured that browser battles continue among enthusiasts, while the average web user is less affected.[4]

Background

[edit]

Tim Berners-Lee along with his colleagues at CERN started the development of the WWW, an Internet-based hypertext system, in 1989. Their studies led to the creation of the HyperText Transfer Protocol, which set the protocols for client-server communication.[5] In 1990, he created the first web browser, WorldWideWeb, subsequently known as Nexus,[6] and made it available for the NeXTstep Operating System, by NeXT.

Other browsers had started to surface by the end of 1992, many of which were based on the Libwww library. These included MacWWW/Samba for the Mac and Unix browsers including Line Mode Browser, ViolaWWW, Erwise, and MidasWWW. These browsers were HTML viewers that needed third-party helpers to display multimedia content.

Mosaic wars

[edit]In 1993, more browsers became available, including Cello, Lynx, tkWWW, and Mosaic. The most influential of these was Mosaic, a multi-platform browser developed at National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA). By October 1994, Mosaic was "well on its way to becoming the world's standard interface", according to Gary Wolfe of Wired.[7]

Several companies licensed Mosaic to create their commercial browsers, such as AirMosaic, Quarterdeck Mosaic, and Spyglass Mosaic. One of the Mosaic developers, Marc Andreessen, co-founded the Mosaic Communications Corporation and created a new web browser named Mosaic Netscape.

There are two ages of the Internet—before Mosaic, and after. The combination of Tim Berners-Lee's Web protocols, which provided connectivity, and Marc Andreesen's browser, which provided a great interface, proved explosive. In twenty-four months, the Web has gone from being unknown to absolutely ubiquitous.[8]

— Mark Pesce, ZDNet

To resolve legal issues with NCSA, the company was renamed Netscape Communications Corporation, and the browser Netscape Navigator. The Netscape browser improved Mosaic's usability and reliability and was able to display pages as they loaded. By 1995, helped by the fact that it was free for non-commercial use, the browser dominated the emerging World Wide Web.

Other browsers launched during 1994 included IBM Web Explorer, Navipress, SlipKnot, MacWeb, and Browse.[9]

While Netscape faced new competition from OmniWeb, Eolas WebRouser, UdiWWW, and Microsoft's Internet Explorer 1.0, it continued to dominate the market for 1995.

First browser war (1995–2001)

[edit]

By mid-1995, the World Wide Web had received a great deal of attention in popular culture and the mass media. Netscape Navigator was the most widely used web browser and Microsoft had licensed Mosaic to create Internet Explorer 1.0,[10][11] which had released with Microsoft Windows 95 Plus! on August 24, 1995.[12]

Unlike Netscape Navigator, Internet Explorer 1.0 was available to all Windows users free of charge, including commercial companies.[13] Other companies later followed suit and released their browsers free of charge.[14] Netscape Navigator and competitor products like InternetWorks, Quarterdeck Browser, InterAp, and WinTapestry were bundled with other applications to full Internet suites.[14]

New versions of Internet Explorer (IE) and Netscape (branded as Netscape Communicator) were released often over the following few years. New features were routinely added, including Netscape's JavaScript (subsequently replicated by Microsoft as JScript) and proprietary HTML tags such as <blink> (Navigator) and <marquee> (Internet Explorer).[15]

Internet Explorer 3 offered nearly identical services like its competitor, Netscape, offering scripting support and implemented the market's first commercial Cascading Style Sheets (CSS).

On September 22, 1997, Internet Explorer 4 was released. The release party in San Francisco featured a ten-foot-tall letter "e" logo. Netscape employees showing up to work the following morning found the logo on their front lawn, paired with greeting card signed "Best wishes, the IE team".[2] The Netscape employees promptly knocked it over and set a giant figure of their Mozilla dinosaur mascot atop it, holding a sign reading "Netscape 72, Microsoft 18", referencing the companies' market share.[16]

During these releases, it was common for web designers to display "best viewed in Netscape" or "best viewed in Internet Explorer" logos.[17] These images often identified a specific browser and commonly linked to a source from which the stated browser could be downloaded. These logos generally recognized the divergence between the standards supported by the browsers and signified which browser was used for testing the pages. In response, supporters of the principle that websites should be compliant with World Wide Web Consortium standards and hence viewable with any browser started the "Viewable with Any Browser" campaign, which employed its logo similar to the partisan ones. Most mainstream websites, however, specified one of Netscape or Internet Explorer as their preferred browser while making some attempt to support minimal functionality on the other.

While Netscape had accrued about 75% of the market share within four months of its release,[18] as a relatively small company deriving the great bulk of its income from what was essentially a single product (Navigator and its derivatives), it was financially vulnerable. Microsoft's resources allowed them to make Internet Explorer available without charge, as the revenues from Windows were used to fund its development and marketing. As a result, Internet Explorer was provided free for all Windows and Macintosh users, unlike Netscape, which was free for home and educational use but would require a paid license for business use.[19]

Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer with every copy of Windows, which had over a 95% share of the desktop operating system market in June 2004,[20] allowing the company to obtain market share more easily than Netscape as customers already had Internet Explorer installed as the default browser. At this time, many new computer purchasers had never extensively used a web browser before. Consequently, the buyer did not have anything else to compare with and little motivation to consider alternatives; any difference in browser features or ergonomics paled in comparison with the set of abilities they had gained with access to the Internet and the World Wide Web.

During the United States Microsoft antitrust case in 1998, Intel vice president Steven McGeady testified that a senior executive at Microsoft told him in 1995 of his company's intention to "cut off Netscape's air supply", although a Microsoft attorney rejected McGeady's testimony as not credible.[21] That same year, Netscape was acquired by America Online for 4.2 billion dollars. Internet Explorer became the new dominant browser, attaining a peak of about 96% of the web browser usage share in 2001.[22]

Second browser war (2004–2017)

[edit]Decline of Netscape and entry of Firefox

[edit]

At the start of Netscape Navigator's decline, Netscape open-sourced its browser code and later entrusted it to the newly formed non-profit Mozilla Foundation — a primarily community-driven project to create a successor to Netscape. Development continued for several years with little widespread adoption until a stripped-down browser-only version of the full suite, which included new features such as a separate search bar (which had previously only appeared in the Opera browser), was created. The browser-only version was initially named Phoenix, but because of trademark issues that name was changed, first to Firebird, then to Firefox. Phoenix was chosen because "Phoenix", implied that it would rise like a phoenix after Netscape Navigator was killed off by Microsoft. This browser became the focus of the Mozilla Foundation's development efforts. Mozilla's Firefox 1 was released on November 9, 2004,[23] and it then continued to gain an increasing share of the browser market until a peak of around 24% in 2010.[24]

In response, in April 2004, the Mozilla Foundation and Opera Software joined efforts to develop new open-technology standards which add more capability while remaining backward-compatible with existing technologies.[25] The result of this collaboration was the WHATWG, a working group devoted to the fast creation of new standard definitions that would be submitted to the W3C for approval.

The growing number of device/browser combinations in use, legally-mandated web accessibility, as well as the expansion of expected web functionality to essentially require DOM and scripting abilities, including AJAX, made web standards of increasing importance during this era. Instead of advertising their proprietary extensions, browser developers began to market their software based on how closely it adhered to standards.[26]

On December 28, 2007, Netscape announced that support for its Mozilla-derived Netscape Navigator would be discontinued on February 1, 2008, suggesting its users migrate to Mozilla Firefox.[27] However, on January 28, 2008, Netscape announced that support would be extended to March 1, 2008, and mentioned Flock alongside Firefox as alternatives to its users.

Internet Explorer

[edit]In 2003, Microsoft announced that Internet Explorer 6 Service Pack 1 would be the last standalone version of its browser.[28] Future enhancements would be dependent on Windows Vista, which would include new tools such as the WPF and XAML to enable developers to build web applications.

On February 15, 2005, Microsoft announced that Internet Explorer 7 would be available for Windows XP SP2 and later versions of Windows by mid-2005.[29] The announcement introduced the new version of the browser as a major upgrade over Internet Explorer 6 SP1.

Microsoft released Internet Explorer 7 on October 18, 2006. It included tabbed browsing, a search bar, a phishing filter, and improved support for web standards (including full support for PNG) — all features already long familiar to Opera and Firefox users. Microsoft distributed Internet Explorer 7 to genuine Windows users (WGA) as a high-priority update through Windows Update.[30] Typical market share analysis showed only a slow uptake of Internet Explorer 7 and Microsoft decided to drop the requirement for WGA and made Internet Explorer 7 available to all Windows users in October 2007.[31] Throughout the two following years, Microsoft worked on Internet Explorer 8. On December 19, 2007, the company announced that an internal build of that version had passed the Acid2 CSS test in "IE8 standards mode" — the last of the major browsers to do so. Internet Explorer 8 was released on March 19, 2009. New features included accelerators, improved privacy protection, a compatibility mode for pages designed for older browsers,[32] and improved support for various web standards. It was the last version of Internet Explorer to be released for Windows XP. Internet Explorer 8 scored 20/100 in the Acid3 test, which was much worse than all major competitors at the time.[33]

In October 2010, StatCounter reported that Internet Explorer had for the first time dropped below 50% market share to 49.87% in their figures.[34] Also, StatCounter reported Internet Explorer 8's first drop in usage share in the same month.[35]

Microsoft released Internet Explorer 9 on March 14, 2011. It featured a revamped interface, support for the basic SVG feature set, and partial HTML video support, among other new features. It dropped support for Windows XP, and only ran on Windows Vista, Windows 7, and Windows Phone 7. The company later released Internet Explorer 10 along with Windows 8 and Windows Phone 8 in 2012, and an update compatible with Windows 7 followed in 2013. This version dropped Vista and Phone 7 support. The release preview of Internet Explorer 11 was released on September 17, 2013. It supported the same desktops as its predecessor.

Starting in 2015 with the release of Windows 10, Microsoft shifted from Internet Explorer to Microsoft Edge (Commonly referred to as Edge). However, the new browser had failed to capture much popularity,[36] thus Microsoft Edge switched from its own browser engine, EdgeHTML, to Chromium's Blink engine in 2020 for all platforms except for iOS, where it kept relying on WebKit due to platform restrictions.[37][38]

Competing desktop and mobile browsers

[edit]

Opera had been a long-time player in the browser wars, known for being lightweight and introducing innovative features such as tabbed browsing and mouse gestures. However, the software was commercial, which hampered its adoption compared to its free rivals until 2005, when the browser became freeware. On June 20, 2006, Opera Software released Opera 9 including an integrated source viewer, a BitTorrent client implementation, and widgets. It was the first Windows browser to pass the Acid2 test. Opera Mini, a mobile browser, has a significant mobile market share. Multiple ports, such as Opera 8.5 for the Nintendo DS and Opera 9 for the Wii, were also released.[39]

On October 24, 2006, Mozilla released Mozilla Firefox 2. It included the ability to reopen recently closed tabs, a session restore feature to resume work where it had been left after a crash, a phishing filter, and a spell-checker for text fields. Mozilla released Firefox 3 on June 17, 2008,[40] with performance improvements and other new features. Firefox 3.5 followed on June 30, 2009, with further performance improvements, native integration of audio and video, and more privacy features.[41]

Apple created forks of the open-source KHTML and KJS layout and JavaScript engines from the KDE Konqueror browser in 2002. They explained that those provided a basis for easier development than other technologies by being small (fewer than 140,000 lines of code), cleanly designed, and standards-compliant.[42] The resulting layout engine became known as WebKit and it was incorporated into the Safari browser that first shipped with Mac OS X v10.3. On June 13, 2003, Microsoft said it was discontinuing Internet Explorer on the Mac platform, and on June 6, 2007, Apple released a beta version of Safari for Microsoft Windows. On April 29, 2010, Steve Jobs wrote an open letter regarding his Thoughts on Flash, and the place it would hold on Apple's iOS devices and web browsers. Web developers were tasked with updating their web sites to be mobile-friendly, and while many disagreed with Steve Jobs's assessment on Adobe Flash, history would soon prove his point with the poor performance of Flash on Android devices. HTML4 and CSS2 were the standard in most browsers in 2006. However, new features being added to browsers from HTML5 and CSS3 specifications were quickly making their mark by 2010, especially in the emerging mobile browser market where new ways of animating and rendering for various screen sizes were to become the norm. Accessibility would also become a key player for the mobile web.[43][44][45]

Google Chrome's entry

[edit]Google released the Chrome browser on September 1, 2008,[46] using the same WebKit rendering engine as Safari and a faster JavaScript engine called V8. Shortly after, an open-sourced version for the Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux platforms was released under the name Chromium. According to Net Applications, Chrome had gained a 3.6% usage share by October 2009.[47] After the release of the beta for Mac OS X and Linux, the market share had increased rapidly.[48]

During December 2009 and January 2010, StatCounter reported that its statistics indicated that Firefox 3.5 was the most popular browser when counting individual browser versions, passing Internet Explorer 7 and 8 by a small margin.[49][50] This was the first time a browser surpassed the Internet Explorer since the fall of Netscape Navigator. However, this feat, which GeekSmack called the "dethroning of Microsoft and its Internet Explorer 7 browser",[51] could largely be attributed to the fact that it came at a time when version 8 was replacing version 7 as the dominant Internet Explorer version; no more than two months later Internet Explorer 8 had established itself as the most popular browser again. Other major statistics, such as Net Applications, never reported any other browser having a higher usage share than Internet Explorer if each version of each browser was looked at individually: for example, Firefox 3.5 was reported as the third most popular browser version from December 2009 to February 2010, succeeded by Firefox 3.6 since April 2010, each ahead of Internet Explorer 7 but behind Internet Explorer 6 and 8.[52]

Google Chrome's dominance and evolving web standards

[edit]

On January 21, 2010, Mozilla released Mozilla Firefox 3.6, which introduced a new type of theme display, 'Personas'. This allowed users to change Firefox's appearance with a single click. Version 3.6 also improved JavaScript performance, overall browser responsiveness, and startup times.[54]

Google released Google Chrome 9 on February 3, 2011. New features introduced included support for WebGL, Chrome Instant, and the Chrome Web Store.[55] The company created another seven versions of Chrome that year, finishing with Chrome 16 on December 15, 2011. Google Chrome 17 was released on February 15, 2012. In April 2012, Google browsers (Chrome and Android) became the most used browsers on Wikimedia Foundation sites.[56] By May 21, 2012, StatCounter reported Chrome narrowly overtaking Internet Explorer as the most used browser in the world.[57] However, the market share between Internet Explorer and Chrome meant that Internet Explorer was slightly ahead of Chrome on weekdays up until July 4.[58] At the same time, Net Applications reported Internet Explorer firmly in first place, with Google Chrome almost overtaking Firefox as the second.[59] In 2012, responding to Chrome's popularity, Apple discontinued Safari for Windows, making it exclusively available on OS X.[60]

The concept of rapid releases established by Google Chrome prompted Mozilla to do the same for its Firefox browser. On June 21, 2011, Firefox 5.0 was the first rapid release for this browser, finished a mere six weeks after the previous edition.[61] Mozilla created four more whole-number versions throughout the year, finishing with Firefox 9 on December 20, 2011. For those desiring long-term support, Mozilla made an Extended Support Release (ESR) version of Firefox 10 on January 31, 2012. Contrary to the regular version, a Firefox ESR received regular security updates plus occasional new features and performance updates for approximately one year, after which a 12-week grace period was given before discontinuing that version number.[62] Those who continued to use the rapid releases with an active Internet connection were automatically updated to Firefox 11 on March 15, 2012. By the end of 2012, however, Chrome overtook both Internet Explorer and Firefox to become the world's most used browser.[63]

During this era, all major web browsers implemented support for HTML video.[64] Supported codecs, however, varied from browser to browser. Then versions of Android, Chrome, and Firefox supported Theora, H.264, and the VP8 version of WebM. Older versions of Firefox omitted H.264 due to it being a proprietary codec,[65] but it was made available beginning in version 17 for Android and version 20 for Windows. Internet Explorer and Safari supported H.264 exclusively on March 14, 2011 with Internet Explorer 9, and on March 18, 2008 with Safari 3.1.[66][67] However, Theora and VP8 codecs could be manually installed on the desktop versions. Given the popularity of WebKit for mobile browsers, Opera Software discontinued its Presto engine upon the release of Opera 15 on July 2, 2013.[68] The Opera 12 series of browsers were the last to use Presto with its successors using WebKit instead. In 2015, Microsoft discontinued the production of newer versions of Internet Explorer. By this point, Chrome overtook all other browsers as the browser with the highest usage share.[69][70] Chrome had supported Windows XP until the end of 2015.[71]

By 2017 usage shares of Opera, Firefox and Internet Explorer fell well below 5% each, while Google Chrome had expanded to over 60% worldwide. On May 25, 2017, Andreas Gal, former Mozilla CTO, publicly announced that Google Chrome won the Second Browser War.[72]

Aftermath

[edit]Due to Google Chrome's success, in December 2018, Microsoft announced that they would be building a new version of Edge based on Chromium and powered by Google's rendering engine, Blink, rather than their own rendering engine, EdgeHTML.[73][74] The new Microsoft Edge browser was released on January 15, 2020.[75] Though Firefox showed a slight increase in usage share as of February 2019, it continues to struggle with less than 10% usage share worldwide.[76] By April 2019, worldwide Google Chrome usage share crossed 70% across personal computers and remained over 60% combining all devices.[77] In June 2022, Microsoft permanently retired Internet Explorer in favor of Microsoft Edge as their sole browser.[78][79] As of January 2023, Microsoft Edge was the 3rd most used web browser having 4.46% as market share.[80] In 2023, Internet Explorer was permanently disabled by Microsoft on most versions of Windows 10.[81]

As of 2023, Microsoft Edge has been noted to promote itself when visiting or searching for Google Chrome. Ignoring user settings, links from Windows integrated features, such as widgets, open in Edge.[82]

In February 2024, Microsoft silently released the User Choice Protection Driver for Windows 10 and 11 that prevent software changes to the default Browser, requiring users make the changes only through Windows settings.[83][84][85] In May 2024, a Chrome extension released by Microsoft maintains Bing as the default search engine.[86]

See also

[edit]- After the Software Wars

- Comparison of web browsers

- History of the web browser

- History of the World Wide Web

- List of web browsers

- Usage share of web browsers

References

[edit]- ^ "Browser Market Share Worldwide - September 2019". Statcounter. September 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ a b Swartz, Jon; Writer, Chronicle Staff (1997-10-02). "Microsoft Pulls Prank / Company takes browser war to Netscape's lawn". SFGate. Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- ^ Andreas (2017-05-25). "Chrome won". Andreas Gal. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ "Did the browser wars finally end in 2014?". ZDNet.

Over the past decade, a lot has changed: Mobile devices now outnumber traditional PCs, and the desktop browser has become much less important than mobile web clients and apps. Apple's mobile Safari and Google's Chrome are now major players, Mozilla is in a time of major transition, and Microsoft is still paying for its past sins with Internet Explorer.

And in 2014, all those players seem to have dug into well-entrenched positions. - ^ "World Wide Web (WWW) | History, Definition, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ "Tim Berners-Lee: WorldWideWeb, the first Web client". www.w3.org. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ Wolfe, Gary (October 1994). "The (Second Phase of the) Revolution Has Begun". Wired Magazine. Retrieved 2012-04-24.

- ^ Pesce, Mark (October 15, 1995). "A Brief History of Cyberspace". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Berghel, Hal (2 April 1996). "Hal Berghel's Cybernautica". Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Elstrom, Peter (22 January 1997). "MICROSOFT'S $8 MILLION GOODBYE TO SPYGLASS". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 29 June 1997. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Thurrott, Paul (1997-01-22), "Microsoft and Spyglass kiss and make up", ITPro Today, retrieved 2022-10-16

- ^ "Windows History: Internet Explorer History". Microsoft.com. 2003-06-30. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Microsoft Internet Explorer Web Browser Available on All Major Platforms, Offers Broadest International Support" (Press release). Microsoft. 30 April 1996. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ a b Berst, Jesse (20 February 1995). "Web-Wars". PC Week. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Proprietary Elements". 2001. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- ^ "Mozilla stomps IE". Home.snafu.de. 1997-10-02. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "The Unwelcome Return of "Best Viewed With Internet Explorer"". Technologizer by Harry McCracken. 2010-09-16. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Zook, Matthew A. (2005). The Geography of the Internet Industry: Venture Capital, Dot-Coms, and Local Knowledge. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-631-23331-2.

- ^ "Roads and Crossroads of the Internet History". NetValley.com. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ^ Levine, Greg (2005-03-01). "IE drops below 90 percent market share". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

- ^ Chandrasekaran, Rajiv (November 1998). "Microsoft Attacks Credibility of Intel Exec". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ "AMO.NET America's Multimedia Online (Internet Explorer 6 PREVIEW)".

- ^ "History of the Mozilla Project". Mozilla. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

- ^ "Market Share". marketshare.hitslink.com. 2010-01-18. Archived from the original on 2010-01-18. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

- ^ "Position Paper for the W3C Workshop on Web Applications and Compound Documents". W3.org. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "The Business Benefits of Web Standards".

In such an increasingly heterogeneous environment, testing each web page in every configuration is impossible. Coding to standards is then the only practical solution.

- ^ "The Netscape Blog". Netscape, AOL. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ^ Hansen, Evan (2003-05-31). "Microsoft to abandon standalone IE". cnet.com. Archived from the original on 2012-08-09. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

- ^ "IEBlog : IE7". Blogs.msdn.com. 2005-02-15. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Evers, Joris. "Microsoft tags IE 7 'high priority update | CNET News.com". News.com.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "IEBlog: Internet Explorer 7 Update". Blogs.msdn.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Window Internet Explorer 8 Fact Sheet" (Press release). Microsoft. March 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Presto and WebKit-based browsers scored 100 in 2008, with Firefox scoring 93 in June 2009.

- ^ "Microsoft Internet Explorer browser falls below 50% of worldwide market for first time". StatCounter. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "StatCounter Browser Versions from Oct 09 to Oct 10". StatCounter. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ https://www.forbes.com/sites/barrycollins/2020/08/07/dont-like-microsoft-edge-you-wont-be-able-to-get-rid-of-it-soon/

- ^ Salter, Jim (2020-01-30). "Browser review: Microsoft's new "Edgium" Chromium-based Edge". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ Parmar, Mayank (2021-05-05). "Microsoft Edge 91 beta comes to iOS with a unified codebase". Windows Latest. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ Kohler, Chris. "Nintendo Announces DS Browser For US". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ "Coming Tuesday, June 17th: Firefox 3". Mozilla Developer Center. Archived from the original on 2009-03-28. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ "Mozilla Advances the Web with Firefox 3.5". Mozilla Europe and Mozilla Foundation. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ KDE KFM-Devel mailing list "(fwd) Greetings from the Safari team at Apple Computer", January 7, 2003.

- ^ "Web Content Accessibility and Mobile Web: Making a Website Accessible Both for People with Disabilities and for Mobile Devices". W3C. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- ^ "Mobile Product Accessibility Testing Resources". Digital.gov. 31 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ^ "When it comes to accessibility, Apple continues to lead in awareness and innovation". TechCrunch. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

- ^ "A fresh take on the browser". Official Google Blog. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ "Market Share". Browser market share. 2009-11-02. Archived from the original on 2009-11-03. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ Firefox 3.5 is world's most popular browser, StatCounter says, Nick Eaton. Seattle blogs. 2009-12-21. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ^ "StatCounter global stats – Top 12 browser versions". StatCounter. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ "Firefox 3.5 surpasses IE7 market share". Geeksmack.net. 2009-12-22. Archived from the original on 2010-05-26. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ "Browser market share trend". Marketshare.hitslink.com. Retrieved 2010-06-25.

- ^ "Google Chrome is Poised to Swallow the Whole Internet—And That's Bad". 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Mozilla Firefox 3.6 Release Notes". Mozilla.com. 2010-01-21. Archived from the original on 2010-05-22. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ "Google Chrome Blog". chrome.blogspot.com. 2011-02-03. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ "Wikimedia Traffic Analysis Report - Browsers e.a." Wikimedia Foundation. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "Google Chrome Overtakes Internet Explorer". Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "StatCounter Global Stats - Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share". Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "Browser market share". Netmarketshare.com. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- ^ "Apple Discontinues Safari Development for Windows". Archived from the original on 2017-10-28. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "Rapidity | Future Releases". Blog.mozilla.org. 2011-08-26. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- ^ "Firefox ESR release cycle | Firefox for Enterprise Help". support.mozilla.org. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ "Chrome Overtakes Firefox Globally for First Time". StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ "Google Chrome gets HTML video support". CNET. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ Holwerda, Thom (2010-01-24). "Mozilla Explains Why it Doesn't License h264 – OSnews". osnews.com. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Oiaga, Marius (2010-06-24). "IE9 Platform Preview 3 HTML5 Evolution: Canvas, Video and Audio Elements Now Supported". softpedia. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

- ^ Fisher, Ken (2008-03-25). "Safari 3.1 on Windows: a true competitor arrives (seriously)". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

- ^ Lawson, Bruce (2013-02-12). "Dev.Opera — 300 Million Users and Move to WebKit". dev.opera.com. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ "Microsoft To Discontinue Internet Explorer, To Launch New Browser For Windows 10". International Business Times AU. 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ Finley, Klint (2016-01-12). "The Days of Microsoft Internet Explorer Are Numbered—But Its Sorry Legacy Will Live On". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ "Updates to Chrome platform support". Google Chrome Blog. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- ^ Andreas (2017-05-25). "Chrome won". Andreas Gal. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ "Microsoft Chromium browser: Everything you need to know". Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ Warren, Tom (2019-02-19). "Microsoft's new Chrome extension lets you resume browsing across Windows 10 devices". The Verge. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ "Upgrading to the new Microsoft Edge". 15 January 2020. Retrieved 2020-01-22.

- ^ Keizer, Gregg (2019-02-01). "Top web browsers 2019: Firefox scores second straight month of share growth". Computerworld. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ "Desktop Browser Market Share Worldwide".

- ^ "Farewell (Again) to Microsoft's Internet Explorer". BBC News. 20 May 2021.

- ^ "Internet Explorer 11 desktop application ended support for certain operating systems". Microsoft. 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Browser Market Share Worldwide". StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

- ^ "RIP Internet Explorer: Microsoft permanently disables browser on most versions of Windows 10". USA Today.

- ^ Bacchus, Arif (2023-07-29). "Microsoft is trying too hard with Edge". XDA Developers. Retrieved 2024-01-08.

- ^ "New Windows driver blocks software that changes default web browser". Techzine Europe. 8 April 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Jones, Luke (8 April 2024). "Windows Updates Introduce Driver Preventing Browser Switch Without Permission". WinBuzzer. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Wiggins, Cameron (10 April 2024). "Microsoft upgrades Windows with user-centric security feature". DevX. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Annoying Windows 11 pop-up pushing Bing on Chrome users is apparently doing the rounds again". TweakTown. 2024-05-03. Retrieved 2024-05-09.

Bibliography

[edit]- DOJ/Antitrust: U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division. Civil Action No. 98-1232 (Antitrust) Complaint, United States of America v. Microsoft Corporation. May 18, 1998. Press release: Justice Department Files Antitrust Suit Against Microsoft for Unlawfully Monopolizing Computer Software Markets

External links

[edit]- A March 1998 Interview with Marc Andreessen about Microsoft antitrust litigation and browser wars

- The Roads and Crossroads of Internet History: Chapter 4. Birth of the World Wide Web by Gregory R. Gromov

- Browser Statistics – Month by month comparison spanning from 2002 and onward displaying the usage share of browsers among web developers

- Browser Stats – Chuck Upsdell's Browser Statistics

- Browser Stats – Net Applications' Browser Statistics

- StatCounter Global Stats – tracks the market share of browsers including mobile from over 4 billion monthly page views

- Browser war, RIA and future of web development

- Browser Wars II: The Saga Continues – an article about the development of the browser wars

- Web Browsers' War – 2012 – An article about web browsers' war in 2012

- Thomas Haigh, "Protocols for Profit: Web and Email Technologies as Product and Infrastructure" in The Internet & American Business, eds. Ceruzzi & Aspray, MIT Press, 2008– business & technological history of web browsers, online preprint

- Browser Market Share Archived 2017-03-15 at the Wayback Machine – current market share of browsers and their versions, desktop and mobile