Bengali science fiction

| Bengali literature বাংলা সাহিত্য | |

|---|---|

(clockwise from top to bottom :) The oldest bengali script The charyapada(top), Kazi Nazrul Islam(Bottom right), Rabindranath Tagore(Bottom left). | |

| Bengali literature | |

| By category Bengali language | |

| Bengali language authors | |

| Chronological list – Alphabetic List | |

| Bengali writers | |

| Writers – Novelists – Poets | |

| Forms | |

| Novel – Poetry – Science Fiction | |

| Institutions and awards | |

| Literary Institutions Literary Prizes | |

| Related Portals Literature Portal Bangladesh Portal | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History |

| Cuisine |

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

Bengali science fiction (Bengali: বাংলা বিজ্ঞান কল্পকাহিনী Bangla Bigyan Kalpakahini) is a part of Bengali literature containing science fiction elements.[1] It is called Kalpabigyan (কল্পবিজ্ঞান lit. 'fictional science'),[2][3][4][5] or stories of imaginative science, in Bengali literature.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][2][13][14][4][15][16] The term was first coined by Adrish Bardhan[17][18][19][20] during his editorship years.

Earliest writers

[edit]

Bengali writers authored various science fiction works in the 19th and early 20th centuries during the British Raj, before the partition of India. Isaac Asimov's assertion that "true science fiction could not really exist until people understood the rationalism of science and began to use it with respect in their stories" is true for the earliest science fiction written in the Bengali language.[21]

The earliest notable Bengali science fiction was Jagadananda Roy's "Shukra Bhraman" ("Travels to Venus"). This story is of particular interest to literary historians, as it describes a journey to another planet; its description of the alien creatures on Venus used an evolutionary theory similar to the origins of man: "They resembled our apes to a large extent. Their bodies were covered with dense black fur. Their heads were larger in comparison with their bodies, limbs sported long nails and they were completely naked."

Some specialists credit Hemlal Dutta as one of the earliest Bengali science fiction writers for his "Rohosso" ("The Mystery"). This story was published in two installments in 1882 in the pictorial magazine Bigyan Darpan.[22]

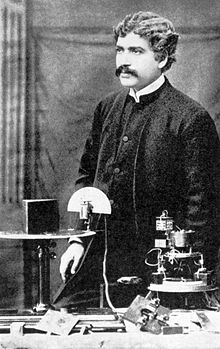

In 1896, Jagadish Chandra Bose, known as the father of Bengali science fiction, wrote "Niruddesher Kahini". This tale of weather control, one of the first Bengali science fiction works, features getting rid of a cyclone using a little bottle of hair oil ("Kuntol Keshori"). Later, he included the story with changes in the collection of essays titled Abyakto (1921) as "Palatak Tufan" ("Runaway Cyclone"). Both versions of the story have been translated into English by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay.[23]

Roquia Sakhawat Hussain (Begum Rokeya), an early Islamic feminist, wrote "Sultana's Dream," one of the earliest examples of feminist science fiction in any language. It depicts a feminist utopia of role reversal, in which men are locked away in seclusion in a manner corresponding to the traditional Muslim practice of purdah for women. The short story written in English was first published in the Madras-based Indian Ladies Magazine in 1905, and three years later, it appeared as a book.

Hemendra Kumar Ray's Meghduter Morte Agomon ("The Ascension of God's Messengers on Earth"), a work inspired by Wells' "The War of The Worlds", describes the first contact between two sentient species. Ray's Martians, instead of invading a metropolis like Calcutta or London, descend to a rural Bengal village called Bilaspur. Though the superstitious villagers call the new arrivals creatures of supernatural chaos, the protagonist, Binoy-babu, a person of scientific temper, says, "This is neither the work of a ghost nor human. This is the work of an unknown force that you will not find on this Earth. That power that scientists all over the world have been seeking has made its very first appearance here, in this Bengal! Oh, Kamal, you cannot imagine how happy I am!"[24] As the father of Bengali adventure fiction, Ray puts the reader through Binoy's narrative. It is divided into two parts, the first is a futuristic, Indianized take on Fermi paradox, and the second is a prehistoric adventure inspired by Wells' The Time Machine. In his later novels, Roy also Indianized Doyle's The Lost World as Maynamatir Mayakanon ("The Surreal Garden of Maynamati"). His "Nobojuger Mohadanob" is considered the first piece of Bengali literature on robots.[2]

Post-colonial Kalpabigyan era in India

[edit]Several writers from West Bengal, India, have written science fiction.[14] Adrish Bardhan, one of the most notable of West Bengal's sci-fi writers, is considered the curator of Bengali science fiction/Kalpavigyan. Under the pen name Akash Sen, he helped with the editorship of Ashchorjo (1963–72), the first Bengali science fiction magazine in the Indian Subcontinent.[25][26][27] While having a very short run, this magazine gave birth to a slew of new literary voices such as Ranen Ghosh,[9][28] Khitindranarayan Bhattacharya,[29] Sujit Dhar, Gurnick Singh,[30] Dilip Raychaudhuri,[31] Enakkhi Chattopadhyay, Premendra Mitra and Satyajit Ray. Ashchorjo also published translated works of Golden Age Western sci-fi, like Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein.[6][7][32][33][34]

At its peak, Bardhan, along with Satyajit Ray, Premendra Mitra and Dilip Raychaudhari, presented a radio program on All India Radio, two broadcasts based on the idea of shared universes, called Mohakashjatri Bangali ("The Bengali Astronauts"), and Sobuj Manush ("The Saga of The Green Men").[35][36]

The first science fiction cine club in India, possibly in Southeast Asia as well, was Bardhan's brainchild.[33][37]

Bardhan also created Prof. Nutboltu Chokro,[38] a science fiction series based on a character of the same name.

Following Bardhan's family trauma, which led to the cessation of Ashchorjo's publication, he relaunched the magazine under the title Fantastic in 1975, with Ranen Ghosh serving as coeditor. The term "Kalpavigyan" made its first appearance in this magazine. Unlike Ashchorjo, Fantastic was not exclusively a science fiction publication; it also included other speculative genres such as fantasy and horror. Despite an erratic publication schedule and a heavy reliance on reprints, Fantastic continued for over a decade before ceasing publication in 2007.[33] In the in-between years, another sci-fi magazine, Vismoy, was edited by Sujit Dhar and Ranen Ghosh but was only published for two years.[33] Magazines like Anish Deb's Kishor Vismoy, Samarjit Kar, and Rabin Ball's Kishor Gyan Biggan are honorable mentions.[33]

Eminent filmmaker and writer Satyajit Ray also enriched Bengali science fiction by writing many short stories ("Bonkubabur Bondhu", "Moyurkonthi Jelly", "Brihachanchu", etc.) as well as a science fantasy series about scientist and inventor Professor Shonku. These stories were created keeping the MG and young adult audience of Bengal in mind, particularly the subscribers of Sandesh, of which Ray was an editor. The last two Shonku stories were completed by Sudip Deb.[39] Ray translated Bradbury's Mars Is Heaven! and Clarke's The Nine Billion Names of God as well. Ray's short story "The Alien" is about an extraterrestrial called "Mr. Ang" who gained popularity among Bengalis in the early 1960s. It is alleged that the script for Steven Spielberg's film E.T. was based on a script for The Alien that Ray had sent to the film's producers in the late 1960s.[40][41][42]

Sumit Bardhan's Arthatrisna is the first steampunk detective novel in Bengali.

Other notable science fiction writers include Leela Majumdar, Premendra Mitra, Ranen Ghosh, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, Syed Mustafa Siraj, Samarjit Kar, Anish Deb,[10] Biswajit Ganguly, Siddhartha Ghosh,[43][44] Suman Sen,[45] Rajesh Basu, Abhijnan Roychowdhury, Krishnendu Bandyopadhyay, Debojyoti Bhattacharya, Saikat Mukhopadhyay, Sumit Bardhan, Rebanta Goswami, Soham Guha,[46] Sandipan Chattopadhyay and Mallika Dhar.

Science fiction in Bangladesh

[edit]After Qazi Abdul Halim's Mohasunner Kanna ("Tears of the Cosmos") was the first modern East Bengali science fiction novel.[clarification needed] After independence, Humayun Ahmed wrote the Bengali science fiction novel Tomader Jonno Valobasa (Love For You All),[citation needed] published in 1973. This book is treated as the first full-fledged Bangladeshi science fiction novel.[citation needed] He also wrote Tara Tinjon ("They were Three"), Irina, Anonto Nakshatra Bithi ("Endless Galaxy"), Fiha Somikoron ("Fiha Equation"), and other works.[citation needed]

Bengali science fiction is considered to have reached a new level of literary sophistication with the contributions of Muhammed Zafar Iqbal.[citation needed] Iqbal wrote the story "Copotronic Sukh Dukho" when he was a student of Dhaka University.[citation needed] This was later included in a compilation of Iqbal's work in a book by the same name. Muktodhara, a famous publishing house of Dhaka, was the publisher of this book. This collection gained huge popularity and a new trend of science fiction emerged among Bengali writers and readers. After this first collection, Iqbal transformed his science fiction cartoon strip, Mohakashe Mohatrash ("Terror in the Cosmos") into a novel. All told, Muhammed Zafar Iqbal has written the greatest number of science fiction works in Bengali science fiction.[citation needed]

In 1997, Moulik, the first and longest-running Bangladeshi science fiction magazine, was first published, with famous cartoonist Ahsan Habib as editor. This monthly magazine played an important role in the development of Bengali science fiction in Bangladesh. A number of new and promising science fiction writers including Rabiul Hasan Avi, Anik Khan, Asrar Masud, Sajjad Kabir, Russel Ahmed, and Mizanur Rahman Kallol came of age while working with the magazine.

Other writers of Bangladesh

[edit]Other notable writers in the genre include Vobdesh Ray, Rakib Hasan, Nipun Alam, Ali Imam, Qazi Anwar Hussain, Abdul Ahad, Anirudha Alam, Ahsanul Habib, Kamal Arsalan, Dr. Ahmed Mujibar Rahman, Moinul Ahsan Saber, Swapan Kumar Gayen, Mohammad Zaidul Alam, Mostafa Tanim, Jubaida Gulshan Ara Hena, Amirul Islam, Touhidur Rahman, Zakaria Swapan, Qazi Shahnur Hussain and Milton Hossain. Muhammad Anwarul Hoque Khan writes science fiction about parallel worlds and mysteries of science and mathematics.[citation needed] Altamas Pasha is a science fiction writer, whose recent book is Valcaner Shopno, published by Utthan Porbo.

Following the footsteps of the pioneers, more and more writers, especially young writers, have started writing science fiction, and a new era of writing has started in Bengali literature.[citation needed]

Science fiction magazines

[edit]After the ceasing of Fantastic, there was a void in science fiction in the Bengali literary space. While popular magazines for young adult readers, such as Shuktara, Kishore Bharati, and Anandamela, have published special issues dedicated to science fiction, new platforms promoting science fiction in Bengali through online web magazines have emerged. Popular web-magazines like Joydhakweb have published science fiction stories.[47]

In 2016, a significant development occurred with the publication of Kalpabiswa (কল্পবিশ্ব),[1][48][49] the first science fiction and fantasy-themed Bengali web-magazine for adult readers. In its themed issues, Kalpabiswa has addressed many themes of Kalpavigyan, as well as of global science fiction, such as feminism in sci-fi, climate fiction, the Golden Age of world science fiction, various punk subgenres, and sci-fi in Japanese literature (i.e. manga and anime). Under the guidance of Jadavpur University, Kalpabiswa held the first Science Fiction Conference of Eastern India in 2018.[50][51][52]

Portrayal of characters

[edit]Most Bengali science fiction authors use different characters for different stories, building them up in different forms according to the theme of the story.

The stories by Muhammed Zafar Iqbal sometimes repeat names but have never used the same character in more than one story.[citation needed]

Qazi Shahnur Hussain, the eldest son of Qazi Anwar Hussain and grandson of Qazi Motahar Hussain, wrote the sci-fi Chotomama Series. These are the adventures of a young Bangladeshi scientist Rumi Chotomama and his nephew.[citation needed]

Satyajit Ray's Professor Shonku is portrayed as an aged man, proficient in 72 different languages, who has created many innovative inventions. He is regularly accompanied by other characters including scientists Jeremy Saunders and Wilhelm Krol, his neighbour Mr. Abinash, his servant Prahlad and his beloved cat, Newton.[citation needed]

In his paper "Hemendra Kumar Ray and the birth of adventure Kalpabigyan",[53] Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay said, "Amaanushik Maanush becomes science fiction by incorporating both science and science fiction, particularly lost race narratives and subverting their positions internally. Amaanushik Maanush can be recognised as science fiction not only because of what it claims as science within the text, but more specifically because it is framed within a cluster of science fiction tales that allows us to identify it as part of a genre. It is in its handling of myth that Amanushik Maanush can be identified more distinctly as kalpabigyan."

Premendra Mitra created the immensely popular fictional character Ghanada,[3] a teller of tell tales with a scientific basis. In an interview with the magazine SPAN in 1974, Mitra said that he tried to keep the stories "as factually correct and as authentic as possible."

In the July 1974 issue of the monthly magazine SPAN, AK Ganguly discusses Premendra Mitra's novel "Manu Dwadash" (The Twelfth Manu), which transports readers to a distant future following near-total devastation from nuclear holocausts. In this post-apocalyptic world, only three small tribes remain, each on the brink of extinction due to radiation-induced loss of procreative ability. The author adeptly navigates the scientific and philosophical complexities arising from this apocalyptic scenario.

Mitra remarks, "If Huxley's "Brave New World" can be regarded as science fiction and it is indeed science fiction par excellence, my "Manu Dwadash" can advance some claim to this title."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Future in the Past: Can Bengali science fiction grow up?". 7 January 2018. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Culture : Bengal : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b বিজ্ঞানী ঘনাদা. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ a b Chattopadhyay, Bodhisattva (2017). "Kalpavigyan and Imperial Technoscience: Three Nodes of an Argument" (PDF). Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 28 (1): 102–112. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Bengali SF history". Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b Guha, Dip Ghosh & Soham (2 June 2019). "Adrish Bardhan (1932-2019) single-handedly put science-fiction in the Bengali reader's imagination". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ a b পরলোকে বাংলার কল্পবিজ্ঞান কিংবদন্তি অদ্রীশ বর্ধন. The Indian Express (in Bengali). 21 May 2019. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ দেখা: অস্তিত্বসঙ্কটে ধুঁকছে বাংলার বিজ্ঞানপত্রিকা ও কল্পবিজ্ঞান. Eisamay (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ a b কলকাতার কড়চা: নব রূপে কাঞ্চনজঙ্ঘা. Anandabazar Patrika (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ a b বিদ্যাসাগর পুরস্কার পাচ্ছেন অনীশ দেব. Eisamay (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "CoFUTURES: Publications". Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "The Short-lived Glory of Satyajit Ray's Sci-Fi Cine Club". 9 May 2018. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Hoene, Christin (2020). "Jagadish Chandra Bose and the anticolonial politics of science fiction". The Journal of Commonwealth Literature. 58 (2): 308–325. doi:10.1177/0021989420966772.

- ^ a b Mondal, N. C. (March 2012). "Popular Science Writing in Bengali - Past and Present" (PDF). Science Reporter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2022.

- ^ Banerjee, Suparno. Indian Science Fiction: Patterns, History and Hybridity. New Dimensions in Science Fiction. University of Wales Press. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023 – via University of Chicago Press.

- ^ "SF History (India)". Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ সায়ান্স আর ফিক্শনের শুভবিবাহ. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ অদ্রীশ বর্ধনঃ যেমন দেখেছি. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ অদ্রীশ গ্যালারী. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ কলকাতার কড়চা. Anandabazar Patrika. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Mutiny, Sepia (7 May 2006). "Early Bengali Science Fiction". Lehigh University. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "SFE: Bengal". sf-encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Runaway Cyclone". Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ Rachanabali 1, 113–114

- ^ Matti Braun's Monograph (Edited by Matti Braun, Beth Citron, Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay). ASIN 3864423104 .

- ^ "Articles on Bengali SF magazine and cine club". Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ ধুলোখেলা - A Bengali Magazine Archive: Aschorjo - First Bengali Science Fiction Patrika - March 1967. 5 May 2015. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ রণেন ঘোষ. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ ক্ষিতীন্দ্রনারায়ণ ভট্টাচার্য – বাংলা কল্পবিজ্ঞানের এক বিস্মৃত অধ্যয়. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ গুরনেক সিং – বাংলা কল্পবিজ্ঞানের আশ্চর্য দিশারী. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ বাংলা সায়-ফি জগতের হারামণি ডক্টর দিলীপ রায়চৌধুরী. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ কল্পলোকে প্রয়াণ অদ্রীশ বর্ধনের. Anandabazar Patrika (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Matti Braun | News". Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ কলকাতার কড়চা. Anandabazar Patrika (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "How Satyajit Ray, Premendra Mitra and two others wrote a science fiction story jointly for the radio". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Roy, Sandip (14 September 2019). "When the 'green men' tearing the world apart look just like us". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Parashuram; Löbke, Matthia (2020). Matti Braun. Snoeck. ISBN 978-3864423109.

- ^ প্রফেসর নাটবল্টু চক্র: অমৃতের সন্ধান, না সময়-নষ্ট?. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Swamohimay Shanku - Satyajit ray, Sudip deb". 22 April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Manas: Culture, Indian Cinema- Satyajit Ray". ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 23 May 2000.

- ^ বন্দ্যোপাধ্যায়, শুভাগত. সত্যজিতের এলিয়েন. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ সত্যজিতের ছবির কল্পবিশ্ব. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ স্বর্ণযুগের সিদ্ধার্থ. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ কল্পবিশ্ব - Kalpabiswa added a... - কল্পবিশ্ব - Kalpabiswa. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023 – via Facebook.

- ^ Suman Sen (2017), Sarpa Manav (Sarpa Manav: Nagmoni Rohosyo ed.), Kolkata: Diganto Publication, OL 26412550M

- ^ বাঙালির চন্দ্রস্পর্শ! নাসার হাত ধরে চাঁদে পাড়ি দিচ্ছে উত্তরপাড়ার তরুণের গল্প. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Websahitya". Aajkaal. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "ওয়েবসাহিত্যঃসূচনা-বিবর্তন-ভবিষ্যত"ঃ একটি আলোচনাসভা. Aajkaal. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Kalpabiswa". Kalpabiswa.

- ^ কলকাতার কড়চা: খাদির ঐতিহ্য সন্ধানে. Anandabazar Patrika. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ কল্পবিজ্ঞানের দুশো বছর. Sangbad Pratidin. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "A science fiction conference in Kolkata showed that the genre has remained alive and well in Bengal". Scroll.in. 16 February 2019. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Hemendra Kumar Roy and the birth of adventure Kalpabigyan" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2012) |

- Science Fiction: Ek Osadharan Jagat.

- Preface of Science Fiction Collection, edited by Ali Imam and Anirudho Alam

- Different issues of Rohosso Potrika

External links

[edit]- Bengal at the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

- Article on Bangla Science Fiction in Science Fiction Studies by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay

- Kalpabiswa web-magazine